The power to control objects with your mind was once a dream held by science fiction fans worldwide. But is this impossible feat now becoming possible? Dr Tracey Camilleri tells Becky Catrin Jones how a team at the University of Malta (UM) is using technology to harness this ability to help people with mobility problems.Continue reading

Transcendence through Play

Even though philosophers like Kant and Schiller of the aesthetic tradition never had the opportunity to troll some noobs in Call of Duty or slay a dragon in Skyrim, their views on the concept of play can be critical to our understanding of how the player relates to the game world. Dr Daniel Vella explores the work of aesthetic and existential philosophers. Words by Jasper Schellekens. Continue reading

The Philosophy of Creativity

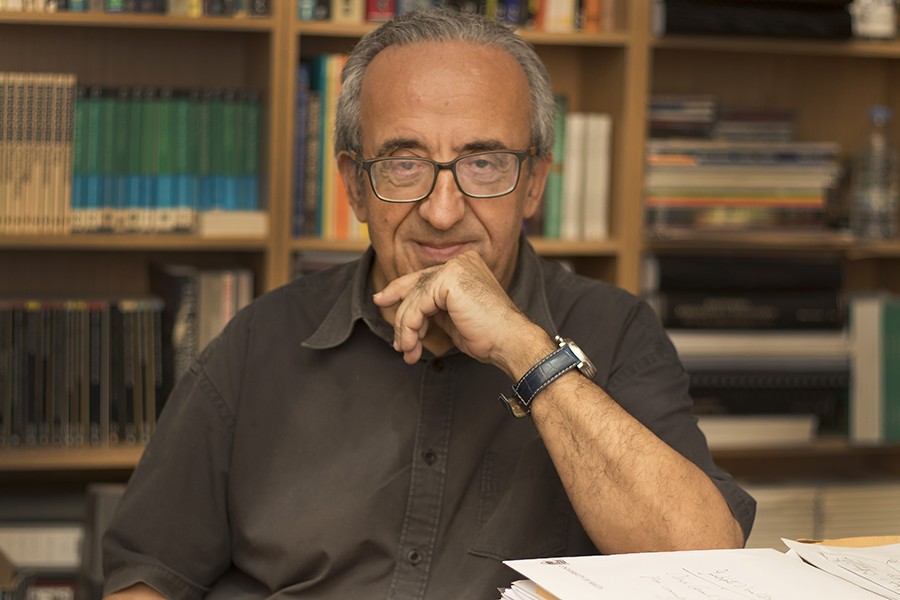

In this age of specialisation, finding a niche is key to most people’s career progression. But it is not the only way. Cassi Camilleri sits down with philosopher poet Prof. Joe Friggieri to gain insight into his creative process.

It was a very warm April day when I found myself sitting in front of Prof. Joe Friggieri. My heart was racing—I had just run up three flights of stairs for a rescheduled meeting after having missed our first earlier in the day. I had lost track of time while distributing magazines around campus. My eyes briefly scanned his library, wishing it was mine, then got right down to the business of asking questions.

Friggieri balances between two worlds: the academic and the creative. His series Nisġa tal-Ħsieb, the first history of philosophy in Maltese, is compulsory reading for philosophy students around the island. His collections of poetry and short stories have seen him win the National Literary Prize three times. I ask Friggieri if he separates his worlds in some way. ‘I can’t stop being a philosopher when I’m writing a short story or play. Readers and critics of my work have pointed that out in their reactions,’ he says. ‘I do not necessarily set out to make a philosophical point in my output as a poet, short-story writer, or playwright, but that kind of work can still raise philosophical issues.’

‘Dealing with matters of great human interest—such as love or the lack of it, happiness, joy and sorrow, the fragility of human relations, otherness, and so on—in a language that is markedly different from the one used in the philosophical analysis of such topics can still contribute to that analysis by creating or imagining situations that are close to the experiences of real human beings,’ Friggieri illustrates.

The urge to write

In reality, Friggieri is usually inspired by day-to-day moments, things normally overlooked in today’s loud and busy world. ‘In my literary works, I am inspired by what I see, hear, and feel; by people and events, by what I read about and by what I can remember,’ he says. It could be anything from a news item to a painting, a whiff of cigarette smoke, a piece of music, or a word overheard at a party. ‘All of that can trigger off an idea. Then, when I’m alone, I seek to elaborate the thought and to convey it to others by means of an image or series of images in a poem, or as part of the plot in a short story or play.’

While on the subject of inspiration and starting points, I wondered: how does Friggieri work? First, he swiftly explains his aversion to using computers for his writing. ‘I do all my writing the old-fashioned way,’ he notes. ‘I use pen and paper. I find it much easier to write that way than on my computer. It feels like my thoughts are taking shape literally as I push my pen from left to right across the page. I think with my pen, much in the same way that a concert pianist thinks with her fingers and a painter with her brush. It’s that kind of feeling that makes me want to go on writing.’ At this point, the subject of the Muse comes up. Is this something Friggieri believes in? ‘Waiting for the Muse to inspire you is just a poetic way of saying you need to have something to write about and you’re looking to find the right way of expressing it,’ Friggieri explains. ‘I write when I feel the urge or the need to write,’ he tells me with a smile.

The sheer volume of work Friggieri has built up over the years seems to imply that he writes daily. But in reality, his workflow is more akin to sprints than a marathon. He tells me deadlines are a good motivator for him to write, providing a tangible goal he can work towards. ‘My first two collections of short stories were commissioned as weekly contributions to local newspapers,’ Friggieri says. ‘That’s how ‘Ir-Ronnie’ was born.’ Ir-Ronnie is a man who finds himself overwhelmed by life’s pressures: family, work and everything in between. As he starts to lose touch with reality, ‘ordinary, everyday living becomes an ordeal for him, an obstacle race, a struggle for survival,’ says Friggieri. More recent works, such as his latest collections of short stories—Nismagħhom jgħidu and Il-Gżira l-Bajda u Stejjer oħra—also reflect this realism, exploring the complexity of interpersonal relations between different people from different walks of life. On the other hand, Ħrejjef għal Żmienna (Tales for Our Times) finds its roots in magical realism, which makes these stories a very different experience for his readers. The books have been well received, with translations into English, French, and German. Paul Xuereb, who worked on the English translation, described the tales as ‘drawing on the dream-world and waking reveries to suggest the ambiguity and often vaguely perceived reality of our lives.’

The Creative Philosopher

When it comes to talking about his other works and creativity, Friggieri often refers to language. When I asked him about his thoughts on creativity and whether he believed everyone to be ‘creative’, his response was positive. ‘As human beings, we are all, up to a point and in some way, creative,’ he says. A prime example is humanity’s use of language. ‘Think of the way we use language. Dictionaries normally tell you how many words they contain, but there’s no way you can count the number of sentences you can produce with those words. Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules. In a very real sense, every individual uses language creatively, in a way that is very much his or her own. I think the best way to understand what creativity is all about is to start from this very simple fact.’

Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules.

Is Friggieri creative when he writes his philosophical papers? ‘Yes,’ he nods. ‘Each kind of writing has its own characteristic features. But creativity is involved in all of them.’ With philosophy, ‘you need more time,’ he notes. ‘You need to know what others have said about the subject, so it involves researching the topic before you get down to saying what you think about it. When it comes to writing a poem or play, you’re much freer to say what you like, much less constrained.’

In fact, Friggieri has five plays under his belt. Here is where the two worlds of academia and creative writing merge. ‘In three of my five full-length plays, I make use of historical characters (Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Socrates) to highlight a number of issues in ethics and aesthetics that are still very much alive today,’ says Friggieri. Taking L-Għanja taċ-Ċinju (Swansong) as an example, Friggieri explains how ‘Socrates defends himself against his accusers by raising the same kind of moral issues one finds in Plato’s Apology. The Michelangelo and Caravaggio plays, on the other hand, highlight important questions in aesthetics, such as the value of art, the relation between art and society, the presence of the artist in the work, the difference between good and bad art, and the mark of genius.’

Talking of theatre, Friggieri remembers how, before writing his first play, he had directed several performances. This was where he learnt the trade and what it meant to have a good production. ‘I have also had the good fortune of working with a group of dedicated actors from whom I learnt a lot. In my view, one should spend some time working in theatre before starting to write for it.’

As time was pressing, and the sun was starting to move away from its opportune place in the window, I asked Friggieri one last question, the one I had been obviously itching to ask. What advice does he have for writers? The answer I got was one I should have expected. ‘Budding writers should write. Then they should show their work to established practitioners in the field. The first attempts are always awkward. As time goes by, one learns to be less explicit and more controlled, to use images to express one’s thoughts where poetry is concerned, to develop an ear for dialogue if one is writing a play, to produce well-rounded characters in a novel, construct interesting plots, and so on. All this takes time, but it will be worth the effort in the end.’ And with that, we had the perfect closing.

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Mind the Gap

The world is changing. Technologies are developing rapidly as research feeds the accelerating progress of civilisation. As a result, the job market is reacting and evolving. The question is: Are people adapting fast enough to keep up? Words by Giulia Buhagiar and Cassi Camilleri.

Mur studja ha tilħaq.’ (Study for a successful future.)

From an early age, most Maltese students are conditioned to think this way. You need a ‘proper education’ to land yourself a ‘good job’. But students graduate, and with freshly printed degrees in hand, they head into the job market only to be disappointed when the role they land seems unrelated to their degree. Yet vacancies are ready for the taking; there are many unfilled jobs in the STEM fields, which create 26% of all new vacancies according to recent research from the National Statistics Office.

So, if there are vacancies available, what is the problem? A skills gap.

Academic qualifications do not guarantee that graduates have the right skills for work. At a conference addressing the skills gap organised by the Malta University Holding Company (MUHC) and the Malta Business Bureau (MBB), Altaro Software co-founder and CEO David Vella confirmed this problem. In previous years, Altaro mostly employed experienced developers; however, increased demand led them to realise that there weren’t enough of these candidates out there for them.

To fill those roles, they extended the call to younger people, but Vella found that they were not fully equipped and ready to go. This was when he realised that they needed to change tactics. ‘Now we realise that we need to start hiring junior people and build up their skills.’ Investment needs to be made by both sides.’

What every relationship needs

Better communication between business and academia could improve the skills gap. However, this kind of engagement is easier to manage in some institutions and industries than others, and bringing those worlds together poses many challenges. At the same conference, MUHC CEO Joe Azzopardi noted how start-ups and small businesses often do not have the resources to organise such exchanges. The wall between them and students is a difficult one to get over. However, there is a new initiative seeking to remedy this situation.

Go&Learn is a project bridging education and industry through an online platform that effectively catalogues training seminars and company visits in a multitude of sectors, for students and educators alike. The initiative has garnered a slew of supporters. Sixty companies from all over the world are listed on the site, including some local names: Thought3D, ZAAR, and Contribute Water, to name a few. This year was Go&Learn’s third edition, and with 17 European regions from across 10 countries involved, it focused on the STEM fields. In Malta, the team behind Go&Learn, also a collaboration between MUHC and the MBB, have worked together to create two new programmes.

One was dedicated to ICT for business, leisure, and commodity. It saw students visit and learn from local companies Altaro, Scope, MightyBox, Trilith, and Flat Number. Students said that the visits helped them achieve a better understanding of the sector and its nuances. ‘For us students, the fact that we are exposed to the internal working of a business’s environment, it’s an eye-opener,’ said University of Malta (UM) student Maria Cutajar. The second was related to food, involving Elty food, Benna, Fifth Flavour, Da Vinci Pasticceria, and Contribute Water. In this case, the opportunity even attracted foreign students. Go&Learn is acting as a vital bridge between education and industry that can help to minimise the skills gap.

The skills gap exists for many reasons: prejudices towards certain industries, lack of information available on others, and much more. However, education can play an important part in fixing this problem.

Bringing STEM to life

The skills gap exists for many reasons: prejudices towards certain industries, lack of information available on others, and much more. However, education can play an important part in fixing this problem. Currently, local systems are falling short of reacting quickly and addressing new needs in industry. A lot of attention is placed on short-term goals such as exams and assignments, rather than the bigger picture and real-world tasks. This kind of attitude in science education tends to be exacerbated by the notion that its subjects are for ‘nerds’ and ‘brainiacs’. This can be a daunting prospect for young children who don’t see themselves as ‘smart enough’. It can drive lots of young talent away from STEM subjects.

We need to bring fresh talent into STEM by showing how exciting, accessible, and relevant the field actually is. The solution, UM Rector Prof. Alfred Vella says, is to start right at the beginning: ‘We need to inspire teachers.’ This includes attracting the best teachers by providing appropriate salaries. Through education, we need to change the impressions given to children about science and what it means. ‘When I was younger, they used to tell me, why do you want to do science? Wouldn’t it be better to be a doctor? Engineers were seen more as grease monkeys,’ Vella said with a smile. Science should be engaging, inspiring, and fun. For this reason, he commends ESPLORA as being ‘the single most important feature in Malta.’ Vella believes classrooms should be an extension of the ESPLORA centre in their efforts to bring science to life. In addition to teachers inspiring future generations, parents also need to see STEM jobs as a good career for their children, and businesses need to show parents that exciting careers are available by pursuing STEM subjects. Without this, early encouragement might be fruitless.

We need to bring fresh talent into STEM by showing how exciting, accessible, and relevant the field actually is. The solution, UM Rector Prof. Alfred Vella says, is to start right at the beginning: ‘We need to inspire teachers.’ This includes attracting the best teachers by providing appropriate salaries. Through education, we need to change the impressions given to children about science and what it means. ‘When I was younger, they used to tell me, why do you want to do science? Wouldn’t it be better to be a doctor? Engineers were seen more as grease monkeys,’ Vella said with a smile. Science should be engaging, inspiring, and fun. For this reason, he commends ESPLORA as being ‘the single most important feature in Malta.’ Vella believes classrooms should be an extension of the ESPLORA centre in their efforts to bring science to life. In addition to teachers inspiring future generations, parents also need to see STEM jobs as a good career for their children, and businesses need to show parents that exciting careers are available by pursuing STEM subjects. Without this, early encouragement might be fruitless.

With more young people taking up STEM subjects, the potential ripple effect will be vast. These future professionals will be able to conduct more research. The enormous benefits to be reaped from having more people excited about STEM subjects means the burden does not fall solely at the feet of teachers and parents. ‘It is also the job of businesses to show the relevance and benefits of STEM,’ says the CEO of the MBB, Joe Tanti. Go&Learn is providing an arena for business to interact with students and for universities to use their influence positively.

Looking ahead

From children’s classrooms to the skills gap in our economy, everything is intertwined. We need a multi-pronged approach to tackle as many aspects as possible and implement lasting changes. For one thing, we need to take a good look at our education system and how it treats STEM subjects. We also need to bring business and education together, enabling them to communicate more effectively. With Go&Learn starting this much-needed shift, the door is open to more innovative initiatives. Who’s in?

Authors: Giulia Buhagiar and Cassi Camilleri

Maltese Gaming Goes Global

With ever more digital games companies opening their doors in Malta, standing out can be difficult. Dawn Gillies talks to Dorado Games co-founder Simon Dotschuweit to find out how a small company is carving out its niche in an industry of big players.

In 1974, long before the Internet was around, Mazewar introduced the world’s first computer-generated virtual world. With a serial cable to connect computers, friends could play over a network, competing with and against one another for the first time. The Internet now allows thousands of people from opposite sides of the globe to battle it out simultaneously in games set in online virtual worlds like World of Warcraft.

Digital gaming is an industry on the rise, and Malta has seen success after success. It’s a multi-billion dollar enterprise, taking in an astounding $30.7 bn globally in 2017 alone according to Statista. In recent years there has been a surge in free-to-play online games. With so many free games competing for our attention, you might wonder where the money comes from. It may seem counterintuitive, but these free online games sometimes generate higher profits than paid counterparts. Multiplayer PC beat ’em up Dungeon Fighter Online reportedly made an astonishing $1.6 bn in 2017.

With more than 30 digital games companies in Malta alone, it’s a competitive industry to take on. Yet Simon Dotschuweit and Nick Porsche have created Dorado Games, launched real-time grand-strategy game Conflict of Nations, and gained over 400,000 customers.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game.

Dorado’s Origin Story

Whilst working for the independent creators, publishers, and distributors of digital games Stillfront Group, Dotschuweit was already mulling over some new game ideas. The game engines, platforms, and building blocks were all at his disposal. What he needed was a collaborator. That was when Nick Porsche appeared on the scene.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game. Their ideas had Stillfront interested. They were in the early stages of building a game, and the endeavour was gaining support. ‘It was going well, and the company wanted to go ahead with it.’ Two years later, Dorado Games was acquired by the Stillfront Group.

When most of us think video games, we immediately think of games consoles. So why choose to create an online game? Or, for that matter, one that’s free?

Dotschuweit says, ‘They’re a lot more fun to do. You have more control. Usually you self-publish. You can do stuff more iteratively. You can release and then improve. With console games, you need a large publishing partner that will take a large portion of the revenue.’ With Dorado constantly striving to improve their online world for players, the ability to continually update was a big draw for them.

The world of online gaming better lends itself to strategy games. With Dotschuweit and Porsche already big fans, their goal was to create a game they wanted to play. Their business model is also better suited to online gaming than consoles. ‘It’s free to play, so we incentivise players to pay for extra features, which doesn’t work well on console.’ This is where the money comes from. Players pay to construct buildings or train their troops more quickly, giving them an advantage over the competition.

But Stillfront’s acquisition of Dorado meant it was decision time for Dotschuweit. He had to choose between keeping his comfortable job with Stillfront, or taking on a new challenge in the startup world. Living in China with his family at the time, the ramifications of that decision were huge. Porsche was already in Malta, incentivised by the Maltese government’s support of new businesses. In the end, Dotschuweit felt the opportunity to join forces was too great to pass up. He made the leap.

The Rise to Success

Money was key. Dotschuweit tells us, ‘We managed to secure quite a sizeable employment-based grant from Malta Enterprise for our company, which was of course a very nice plus. And Malta is a really nice place!’ The grant not only helped Dorado win over investors, but it reduced risk in an industry that’s infamous for its kill rate, both in-game and in real life. Suffice to say that coming out on top in the gaming world is not guaranteed.

Working in a start-up was also a change for Dotschuweit. Having previously worked for US tech giant IBM, he wanted to make a mark with this new venture. ‘You get to have a lot more impact. Your presence matters a lot more to a small business; it’s a lot more fun. You get to wear lots of hats and get a lot of experience.’ The busy and exciting nature of a small business appealed to him much more than clocking in to a regular office job.

The good times continued rolling with more support coming in from the University of Malta’s (UM) Centre for Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation (CEBI). CEBI houses the TAKEOFF programme which supports new businesses and provides facilities for them. Dr Joseph Bartolo and Prof. Russell Smith are familiar names when it comes to Maltese start-ups, and they have both been an influential part of Dorado’s story. They now operate from the TAKEOFF building on UM’s Msida campus.

But Dorado’s journey is not all smooth sailing. ‘We are a live service and we don’t have separate teams for operations and expansions, so that sometimes means your plans change!’ explains Dotschuweit. It’s all hands on deck to fix any problems. ‘It’s part of the bane and the fun of operations. But it doesn’t get boring!’ he says. This means that a day of meetings can quickly turn into a hectic day of making sure the game is running smoothly. They don’t want to disrupt players’ gameplay if they can avoid it.

In the past, Dorado hired game developers to bring their ideas to life. But this modus operandi changed when it came to Conflict of Nations. With this project, Dotschuweit and Porsche wanted more control, and they were ready to invest. They dug their heels in and hired their own team.

A game of political and military tactics with elements of espionage, Conflict of Nations requires real-world diplomacy skills to move up in the world. Unlike most other strategy games, it takes place right here on Earth, making use of Google Maps to make the game truly global.

Bringing their dream team to life was a challenge. ‘Finding talent back then wasn’t the easiest thing,’ says Dotschuweit. But their perseverance has seen them build a close-knit team who have all contributed to Dorado’s success.

The quest for perfection is a common theme in Dorado’s story. The perfect team, the perfect platform, the perfect game. Their commitment to giving players the best possible experience is a testament to their investment in their projects. Taking the time to get the right team together has proved to be one of the many reasons for Dorado’s fast climb up the games industry ladder. Another was getting their game out quickly to get fan feedback as soon as possible. The Stillfront platform restricts them somewhat in their design, as it wasn’t made specifically for Dorado, by Dorado, but it has reduced their workload massively, allowing them to get Conflict of Nations launch-ready in a fraction of the time. Identifying and taking advantage of opportunities has also been key to their quick rise.

Many Lessons Learnt

In the crowded world of online games, Dorado games has skillfully managed to carve out its place. Real-time negotiations and political tactics in Conflict of Nations are the stand-out features for fans who enjoy the long timescales and mental strategy involved. With this victory under their belt, we’ll soon see more from Dorado. They have plans to develop another game this year.

With years of experience in the industry, Dotschuweit has some advice for any future gaming entrepreneurs. ‘Get it out fast and get feedback. You can always improve it later.’ He notes the success of game jams in turning ideas into businesses and urges people to get involved. So, what are you waiting for?

Author: Dawn Gillies

Don’t shy away from inspiring others

A frontline fighter for Malta’s accession into the European Union and former Head of Representation of the European Commission office in Malta, Dr Joanna Drake speaks to Teodor Reljic about how she got where she is, and what keeps her going.

While it may have taken a few hard knocks of late, the European Union (EU) is still a cornerstone in the lives of the continent’s citizens. And with the rising tide of populism the world over, fuelled by values which are the polar opposite of the EU’s unity-in-diversity model and putting into question the sustainability of the EU, it becomes easy to forget about its advantages.

It also becomes easy to forget just how impassioned and hard-fought the road towards accession was for some countries—Malta included. For millennials, the EU referendum in 2003 was, in many ways, our first truly ‘political’ moment. Beyond the rote rhythms of party politics, the event gave us the feeling that something larger than us was happening. History was being shaped right in front of our eyes.

But as this moment ossifies into nostalgia for some, and others edge towards a rising euroscepticism, one person that holds steadfast to the EU and all that it stands for is Dr Joanna Drake.

Acquiring her Doctorate in Laws from the University of Malta in 1988 was the spark that paved the way for an eclectic career for Drake. She prefers to characterise it as ‘varied with lots of spice’, and it is one in which the EU has played a central part from early on.

‘Yes, throughout everything, there has been a major common thread—the European Union. I pride myself in having such a powerful and inspiring reference point in my career. It has opened so many doors, and it keeps on being enticing in the challenges it presents,’ Drake says.

It has been a journey with many rungs and steps along the way… all of which Drake diligently and patiently takes the time to enumerate during our conversation.

Vote Yes

In 1990, Drake’s world transitioned from the academic to the professional. She joined Malta’s first-ever professional team at the Malta Foreign Office, which was charged with preparing Malta’s EU membership application —a seed that would of course bear its most significant fruit just over a decade later.

Another significant step forward came five years later, when Drake took up teaching at her alma mater for a period that would last from 1994 to 2002. The position was no small feat. It meant that, at the relatively tender age of 30, Drake was lecturing in the Department of European and Comparative Law (Faculty of Laws) at both undergraduate and postgraduate level.

‘I was humbled to be teaching EU law to many of Malta’s preeminent lawyers, judges, magistrates, journalists, researchers, and politicians, including those who went on to become prime ministers and Presidents of the Republic,’ Drake reminisces, adding how her experience also dovetailed into the private sector. This part of her career overlapped with the ‘EU Moment’, as Drake served as Head of Legal and Regulatory Department for Vodafone Malta Limited from 2000 to 2005, during a stretch of time she describes as being a ‘very challenging period of transition for Malta’s telecommunications sector’.

Juggling so many high-profile, high-responsibility jobs was a big challenge for Drake, especially considering the social expectations on women. But she is quick to point out that all of that has its own silver lining. ‘Being a woman from a non-privileged background and facing tough competition, and even betrayals, including by those whom you had loved and respected, all go towards galvanising your resilience and bringing out the best in you while allowing you to grow.’

Despite such hardships, Drake has not been stopped from living a fulfilling life. ‘Of course, during this period, my private life did not stand still: I was also bringing up my two adorable kids, with whom I have been blessed and who continue to enrich my life every day…’

For millennials, the EU referendum in 2003 was, in many ways, our first truly ‘political’ moment.

Drake’s value of human rights and justice have given her career a crucial focus point, which would reach its critical point come 2003. Serving as the Chair of the YES referendum campaign, whose Maltese-language rallying call ‘Moviment IVA Malta fl-Ewropa’ is bound to stir memories in all those who experienced it, Drake remains unequivocal about the importance of this position for her.

‘My direct and visible political involvement in persuading the Maltese voters to vote YES in the EU referendum of March 2003 is something I remain immensely proud of. Standing up to be counted is always something that resonates deeply with me, and I would say that my involvement with the referendum was an ideal example of all that.’

Malta’s successful entry into the EU led to another key stepping stone in Drake’s career. In 2005 she took on the role of the Head of Representation of the European Commission office in Malta. She was then promoted to Director of Entrepreneurship and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) as well as deputy SME Envoy. She now serves as Deputy Director General in the Directorate-General (DG) Environment in Brussels.

As deputy SME Envoy, she was directly involved in shaping EU policy and helping SMEs face contemporary challenges, like the rise of industries such as Airbnb and UBER. This work yielded positive results in her previous posting as Director of SMEs and Entrepreneurship at DG GROW, where she represented the Commission in high-level dialogues and negotiations in China, US, Tunisia, Abu Dhabi and most EU member states.

It was also a post that allowed her to deliver presentations at numerous major events, cementing a career built on both practicality and advocacy.

The University of Life

With such an impressive CV in hand, I wanted to find out what drove Drake to such success. And it turns out that the University of Malta helped lay the groundwork of some good habits for her.

‘I’ve learnt plenty of lessons along the way, and I keep discovering new ones all the time! But I would certainly highlight the following: passion helps you achieve your goals. Keep investing in knowledge and real friendships. Networking is key. Keep it simple. Reach out, always. Stay humble. Don’t shy away from inspiring others. Take every opportunity to grow as a person, and in your conscience,’ Drake emphasised, adding that: ‘These are some of the stimulants that make my getting up in the morning and going off to work so much more worth it.’

Building your career is about adding your personal value to what you have learned and churned out at university. If those ingredients are in place, a true professional may very well be born.

And what about the new generation of graduates or to-be graduates? Students which, we should point out, have reaped the benefits of EU accession and all that that implies? Drake’s advice to any who dream of following a similarly heady and rewarding path is quite simple, though it requires both commitment and passion. ‘Keep an open mind as to how and where you could deploy your newly learned skills,’ Drake says—a reminder that self-knowledge and self-awareness truly go a long way.

In fact, Drake is keen to stress that a career—as opposed to a one-off and possibly dead-end job—is something that requires the full implementation of your personality and the gravitational pull of your most deeply held passions.

‘So in this way, building your career is about adding your personal value to what you have learned and churned out at university. If those ingredients are in place, a true professional may very well be born. Think about this when preparing for your next interview.’

Her parting-shot of advice is, however, far more to the point, but it resonates all the same: ‘Remember to just enjoy the journey! It’s loads of fun.’

Author: Teodor Reljic

Talking Toys

While speech development starts early in life, the course of acquiring and processing language in a bilingual country like Malta is challenging. Engineers and language experts at the University of Malta have teamed up to build a toy that will help children overcome that hurdle. Words by Emanuel Balzan.

Toys and play are critical in children’s lives. It is through play that children learn how to interact with their environment and other people while developing their cognitive, speech, language, and physical skills.

The way children play reveals many things including whether or not they are hitting particular development milestones. Play is also used by professionals who intervene when those skills are not acquired. Speech and language pathologists (SLP) use toys to tailor tasks based on their objectives for the child, determined following their assessment. For this reason, toys are vital tools.

With technology moving at the rate it is, electronic components are easier and cheaper to access. As a result, a lot of smart, educational toys are now available on the market. However, Dr Ing. Philip Farrugia (Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, UM) honed in on a gap in the market—a smart toy that supports English and Maltese.

To make this happen, Farrugia recruited a team of researchers from the university. Engineers Prof. Simon Fabri and Dr Owen Casha joined the effort. Researchers Prof. Helen Grech and Dr Daniela Gatt brought their expertise in speech and language acquisition and disorders. The team was finally complete when game development company Flying Squirrel Games stepped into the picture.

Getting down to business

The SPEECHIE project is divided into three stages. During the first phase, we sought to understand the process of speech and language acquisition, assessment, and therapy. We involved users through workshops that allowed us to observe children’s play and their toy preferences. We also conducted focus groups with parents to identify what they most wanted from toys. During these sessions, one parent noted how ‘there are not any [educational] toys in Maltese our little ones can play and interact with.’ Others agreed with this observation. Parents also raised concerns about children’s attraction to tablets and smartphones, noting how they interfered with social interaction. On the tail end of this discussion, one parent quickly added that ‘the toy must have something to make it feel like a toy and not a gadget.’

With further questioning, we also came to realise that different parents have different criteria when deciding to buy a toy. One parent told us that before buying a toy for her daughter, she would ‘try to see for how long she will play with it and what the toy will give her in return.’ Another parent, concerned about toys’ safety, checks for the CE mark (Conformité Européene) prior to purchasing the toy, saying that he associates the mark with better quality. However, he also confessed that ‘in the hands of children, nothing remains of quality. Give them something which is unbreakable and they will manage to break it in one way or another.’

With further questioning, we also came to realise that different parents have different criteria when deciding to buy a toy. One parent told us that before buying a toy for her daughter, she would ‘try to see for how long she will play with it and what the toy will give her in return.’ Another parent, concerned about toys’ safety, checks for the CE mark (Conformité Européene) prior to purchasing the toy, saying that he associates the mark with better quality. However, he also confessed that ‘in the hands of children, nothing remains of quality. Give them something which is unbreakable and they will manage to break it in one way or another.’

Since our toy is intended for use in speech therapy, we went ahead and organised more focus groups with SLPs. Outlining the role of toys in their clinics, SLPs said ‘[they] are normally used as a reward. If you know that this child likes blocks, then you use them to motivate the child.’ Toys are also used as part of the language tasks SLPs give. ‘We use objects to put a grammatical structure in a sentence. Many times you find something that represents a noun, a verb, an object and then put them together’ to model the appropriate sentence construction. This prolific use of toys, however, brings with it a very practical problem. One SLP explained how challenging things can get on a day-to-day basis due to the lack of multipurpose toys. ‘We are always carrying toys… we are always carrying things around with us. Even our cars… it is like I have ten kids,’ she said.

To address this issue, SLPs emphasised how useful it would be to have a flexible toy with multiple functions. One that does not bore children and which they can use to target different speech and language therapy goals. They also drew our attention to a prevalent but damaging mentality that they are trying to address. ‘Unfortunately, the majority of Maltese parents have a mentality that the more money they spend and the more therapy sessions for their children, the sooner the problem is alleviated, but in reality this is not true. The work needs to continue at home on a daily basis. It is not solely our responsibility,’ the SLP said. Much like when we practice daily to learn to play an instrument, speech and language therapy works the same way.

Sharon Borg, an experienced occupational therapist from the government’s Access to Communication and Technology Unit, said that the toy we had in mind could provide a simple way for parents to engage with their children and work at home on related exercises. Borg’s colleague, Ms May Agius, also noted the need for the toy to offer ‘surprises’, saying that ‘anticipation and elements of surprise draw kids and keep them engaged.’

Here we have only touched the surface of all the ideas brought forth. However, by considering the children’s, therapists’, and parents’ needs early in the engineering design process, we should be able to reduce the number of design iterations we have in future.

Reaching out

Design is key. Based on the feedback from the focus groups, we have now started working on the hardware and the software. But the journey is not straightforward. One issue we needed to deal with was the lack of compatibility between the 3D modelling software Flying Squirrel Games used and the technology used by the UM. From an academic point of view, because of the innovative nature of the toy we are making, we needed flexibility, so we modified Flying Squirrel’s virtual model to add different mechanisms which involve moving parts. These alterations now allow us to create support to fix electronic components within the device and ensure that no moving part is impeded by another part. As a result, assembly is much easier.

We have also made the decision to build SPEECHIE software using modular blocks. This will enable us to switch parts and functions around so we can widen the idea of who might enjoy our product. The toy will not only be of use to children with speech and language impairments, but also to others. This approach was inspired by a meeting with behavioural economist Dr Marie Briguglio who warned us that labelling the toy could be stigmatising. She explained that it should not become ‘an isolated toy which kind of becomes a label: because I have this toy, that means I have speech impairment.’

Despite the aversion some parents felt towards technological devices, as said during focus groups, Borg also encouraged us not to shy away from using them. She said children with autism responded very well to technology, and therapists will make the best choice for the child to improve their skills. To hit a sweet spot in between these views, we are incorporating functions that will allow for a kinesthetic learning experience that involves physical activities rather than passive consumption of instructions. We want to mix different modes of play to encourage effective learning. We do not want kids to sit and watch their toy, but to move around, dance, and sing with other children.

With all of these choices under our belt, we now have a working prototype. But the SPEECHIE toy is not yet complete. In fact, the coming months will see us working on the mechanisms and the interfacing of electronics.

Towards the end of the year, we will start putting the toy into preschoolers’ hands to determine its effectiveness and efficiency in regard to speech and language therapy. To do this, we will compare the progress of children who use SPEECHIE with those who only use traditional SLP methods.

What we hope is that this toy will encourage parent-and-child interaction through play. We want to enable more frequent use of both Maltese and English and allow children to be safely exposed to technology and to a fantastic learning experience—all while having a ball.

Note: We are excited to share these insights about SPEECHIE with the public, and if you would be interested in joining on this journey by participating in the evaluations, get in touch here: speechie-web@um.edu.mt

This research is financed by the Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) through the FUSION Technology Development Programme 2016 (R&I-2015-042-T).

Author: Emanuel Balzan

Spotting marine litter

Marine litter is a problem found across the world. As well as being directly deposited in seas and oceans, plastic, wood, rope, and other items are accumulating on land and making their way into bodies of water. On the Maltese Islands, such littering happens frequently. Last summer the Physical Oceanography Research Group (Faculty of Science, University of Malta [UM]) took a step towards tackling the issue.

Under the supervision of Prof. Alan Deidun and Adam Gauci, I sought to harness innovative techniques and create a monitoring programme that would begin to identify what kind of litter is on Malta and Gozo’s beaches.

The national Marine Strategy Framework Directive was followed to ensure good data collection and meeting of the ‘Good Environmental Status’ by 2020. The study used images captured by a drone in three coastline areas: the north east Marine Protected Area of Malta, Qawra Point, and the eastern and western points of Baħar Iċ-Ċagħaq. Flying at an altitude of 30 meters, the drone was programmed to spot specific categories of marine and coastal litter. These included plastic, wood, rope, rubber, and other miscellaneous items such as washing machines and mattresses.

Apart from characterising marine litter, the project aimed to observe whether hydrodynamical phenomena, such as wind and currents, are also influencing the accumulation of litter. However, results showed that the difference between the areas of study was not due to dynamics of coastal currents and coastal topography, but to human activities. In Baħar iċ-Ċagħaq, for example, categories such as wood and plastic were found on land at considerable distances from the shoreline, close to points easily accessible by cars.

We also used statistical analyses to confirm that parameters such as tourism, lack of public knowledge, and lack of environmental consciousness are affecting the accumulation of marine litter, laying the blame firmly on human activities.

The remedy to the situation is in Maltese citizens’ hands. Only we have the power to turn things around. It’s time to clean up our act.

This research was carried out as part of a Masters in Physical Oceanography, Faculty of Science, UM.

Author: Serena Lagorio

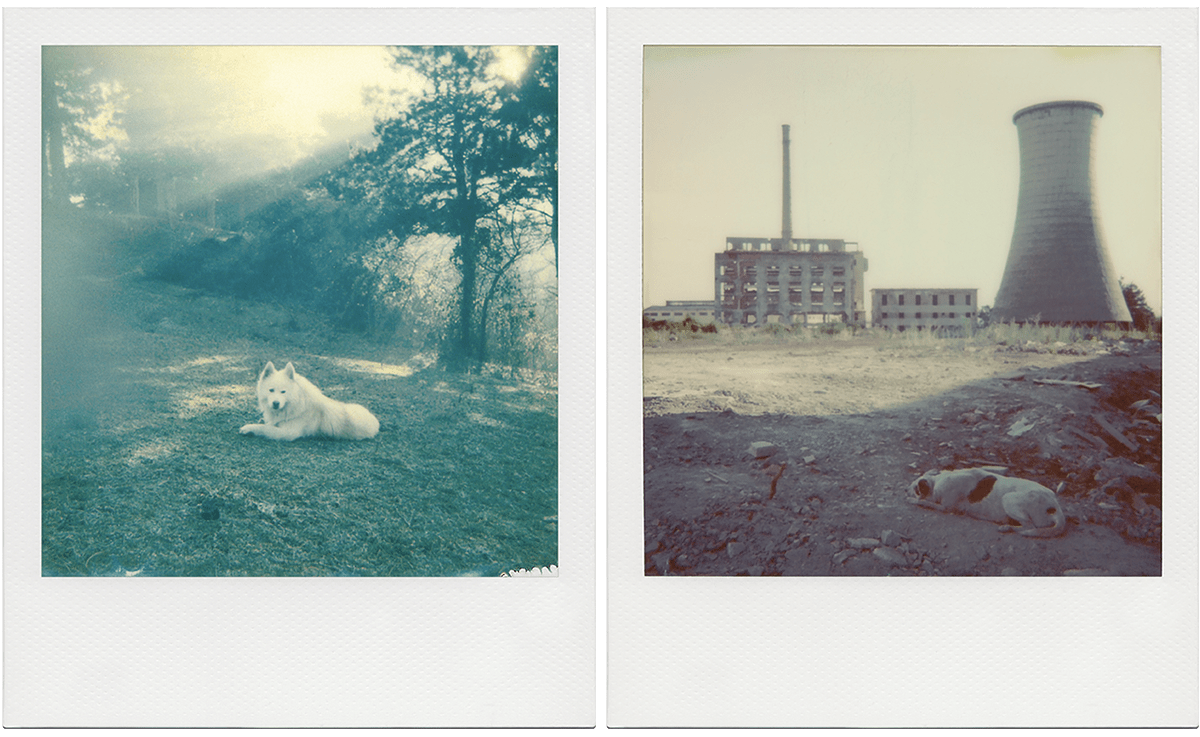

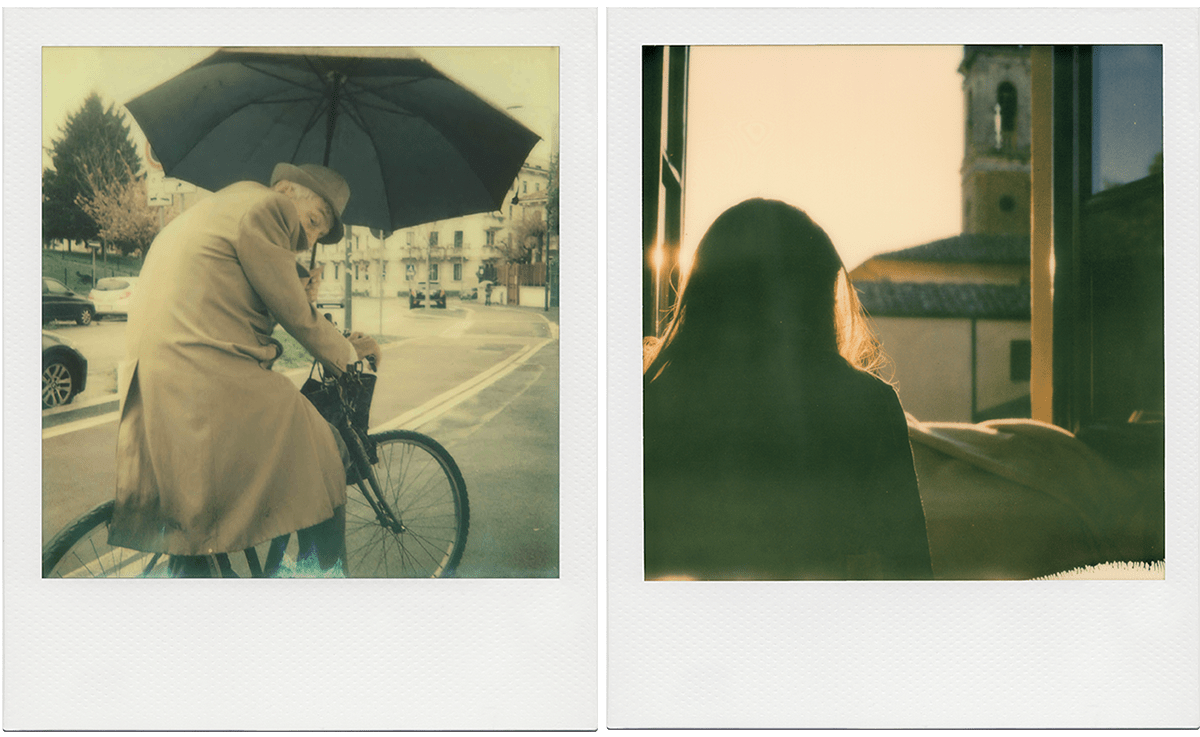

Instant Photography

Instant cameras, commonly referred to as ‘Polaroids’ thanks to the pioneering company, offer limited manual-automatic controls. These self-developing photographs present numerous analog imperfections, but additional aspects make them distinctive.

Polaroids do not document the world faithfully. They create a new version of it through their own lighting schemes, colours, and softness; a quality associated with past technologies. All these aspects enhance the transient nature of subjects, such as boy counting in during a game of hide-and-seek (see picture).

The process of capturing an image can also draw from ‘missed opportunities’. These are subjects one comes across but does not photograph due to not having a camera at hand, or for fear of intrusion. A line of people coming down a hill, or visitors waiting like purgatorial souls outside a derelict hospital—such images are captured in the mind and their essence might be transferred into other shots.

Having the image in hand within minutes does not necessarily make the medium of instant photography unique, for even the photos themselves can change hues and mood with time. What does make it unique is its unpredictability and the challenge it poses when it comes to materialising intentions within the limitations of the medium. This makes the effort worth pursuing.

An image illustrates the relationship between a subject and its viewer. It is a perspective on the world, be it a printed photograph, a digital file, or a memory.