For many of us, video games are a fun way to spend an evening. However, for some, video games are an integral part of our lives. When we’re not playing them, we’re reading about them, trawling through forums and ‘let’s plays’, and making them. The Global Game Jam brings together like-minded people for an intense three days of developing a game from scratch.

Continue readingDesigning a Dream

Can we reduce the level of pain perception in the brain? Distraction therapy has been used by health professionals for years to help children and young people cope with painful procedures. The aim is to take the focus of the patient away from the pain and concentrate on something else instead. Books, games, music, and toys are some of the many types of distraction therapy.

Continue readingCome ‘Here’!

A pointed index finger can mean many things. It can direct our attention to something, show us which way to go, or demand silence. It all depends on context—the situation in which it is used. This is what philosophers refer to as ‘indexicality’. And yes, you guessed it, the word ‘indexicality’ comes from the name of that particular finger.

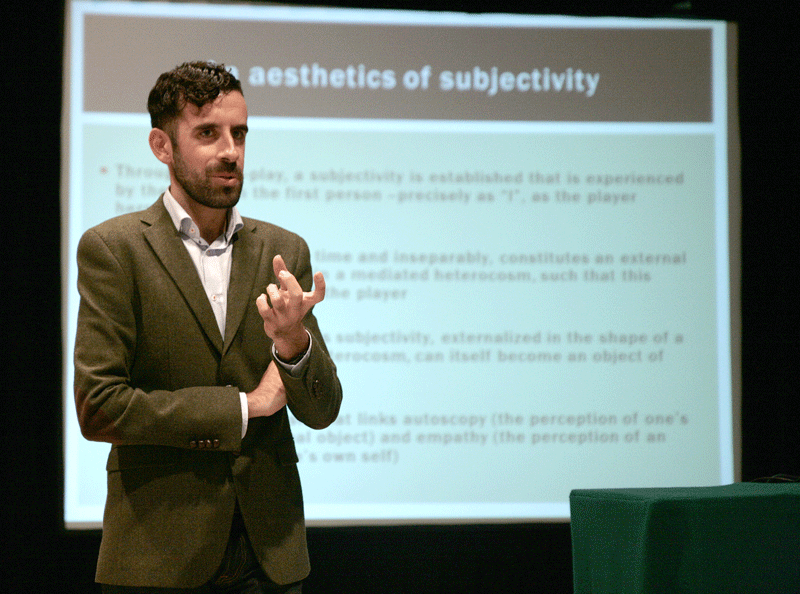

At the University of Malta’s Institute of Digital Games, Prof. Stefano Gualeni has been playing around with this concept. Featuring the voice acting talents of independent game developers Emily Short and Pippin Barr, Gualeni has created a video game called Here, designed for players to engage with (and get confused by) the concept of indexicality.

Here’s gameplay poses the question of what it means when we say ‘here’ in a game world, and how many meanings of ‘here’ can exist side-by-side in a video game. It uses the trope from Japanese Role Playing Games of going on quests to retrieve bizarre items from classic locations. Spooky caves and castles are all part of the repertoire of locations that players can explore. But then, where do you go if ‘here’ is your instruction? What if ‘here’ isn’t where you think it is? What if you’re supposed to go upside down instead?

To try the game yourself, visit www.here.gua-le-ni.com

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Escape the (Virtual) Room!

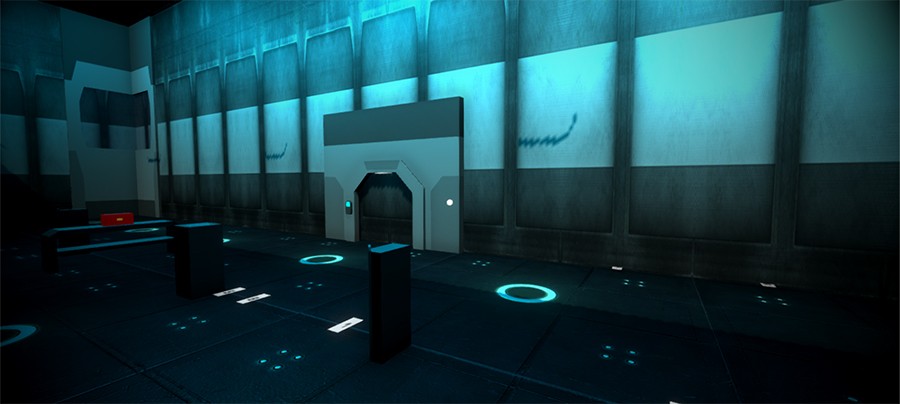

Virtual Reality (VR) has created a whole new realm of experiences. By placing people into varied situations and environments, VR enables them not only to explore, but to challenge themselves and gain skills in ways never thought possible. With applications in medical and psychological treatment, VR is now being used to train surgeons, treat PTSD, and to help people understand what it’s like to be on the autism spectrum. The key to this application is VR’s ability to immerse its users.

Many agree that immersion needs two key ingredients: a sense of presence and interaction with the environment. Interaction comes in three main forms. Selection is about differentiating between items in the environment. Navigation allows travelling from one point to another and observing the environment. Finally, manipulation lets users grab, move and rotate selectable items. In addition to this, VR applications need a setting. Supervised by Dr Vanessa Camilleri and Prof. Alexiei Dingli, I chose to use escape rooms (adventure games where multiple puzzles are solved to leave a room) to experiment with these interaction techniques.

I used escape rooms because they’re highly interactive and naturally immersive systems. And since interaction isn’t a one-size-fits-all scenario, I also applied procedural content generation (PCG) techniques to create the escape rooms themselves.

People selected items using a reticle, a small circle in the middle of the screen which expands or contracts to indicate which objects they could interact with. They navigated the space by looking around through the VR headset and moving their joystick. They manipulated puzzles from a separate screen which I layered on top of the escape room. This allowed them to inspect objects to their heart’s content, while also reducing the amount of clutter in the room.

Since there was no previous work in PCG escape rooms, I had to pave my own way. I used a genetic algorithm, a machine learning algorithm that mimics evolution in biology to select the best solution to a problem, to determine which puzzles and items would be placed in the escape room. I also programmed the game to create the rest of the room, placing floors, ceilings, and everything else that the algorithm didn’t consider. This made the space look like it had been made by an actual person, despite being created through AI.

From the results gathered, most people found that the system allowed them to explore the VR environment in a very natural way. Players said that the room’s generated interaction was consistent, reliable, and fun.

Understanding immersion is critical for VR’s future applications. If we can help people hone these techniques by creating a few games along the way—so be it!

This research was carried out as part of a Bachelor of Artificial Intelligence at the Faculty of ICT, University of Malta

Author: Natalia Mallia

Transcendence through Play

Even though philosophers like Kant and Schiller of the aesthetic tradition never had the opportunity to troll some noobs in Call of Duty or slay a dragon in Skyrim, their views on the concept of play can be critical to our understanding of how the player relates to the game world. Dr Daniel Vella explores the work of aesthetic and existential philosophers. Words by Jasper Schellekens. Continue reading

Maltese Gaming Goes Global

With ever more digital games companies opening their doors in Malta, standing out can be difficult. Dawn Gillies talks to Dorado Games co-founder Simon Dotschuweit to find out how a small company is carving out its niche in an industry of big players.

In 1974, long before the Internet was around, Mazewar introduced the world’s first computer-generated virtual world. With a serial cable to connect computers, friends could play over a network, competing with and against one another for the first time. The Internet now allows thousands of people from opposite sides of the globe to battle it out simultaneously in games set in online virtual worlds like World of Warcraft.

Digital gaming is an industry on the rise, and Malta has seen success after success. It’s a multi-billion dollar enterprise, taking in an astounding $30.7 bn globally in 2017 alone according to Statista. In recent years there has been a surge in free-to-play online games. With so many free games competing for our attention, you might wonder where the money comes from. It may seem counterintuitive, but these free online games sometimes generate higher profits than paid counterparts. Multiplayer PC beat ’em up Dungeon Fighter Online reportedly made an astonishing $1.6 bn in 2017.

With more than 30 digital games companies in Malta alone, it’s a competitive industry to take on. Yet Simon Dotschuweit and Nick Porsche have created Dorado Games, launched real-time grand-strategy game Conflict of Nations, and gained over 400,000 customers.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game.

Dorado’s Origin Story

Whilst working for the independent creators, publishers, and distributors of digital games Stillfront Group, Dotschuweit was already mulling over some new game ideas. The game engines, platforms, and building blocks were all at his disposal. What he needed was a collaborator. That was when Nick Porsche appeared on the scene.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game. Their ideas had Stillfront interested. They were in the early stages of building a game, and the endeavour was gaining support. ‘It was going well, and the company wanted to go ahead with it.’ Two years later, Dorado Games was acquired by the Stillfront Group.

When most of us think video games, we immediately think of games consoles. So why choose to create an online game? Or, for that matter, one that’s free?

Dotschuweit says, ‘They’re a lot more fun to do. You have more control. Usually you self-publish. You can do stuff more iteratively. You can release and then improve. With console games, you need a large publishing partner that will take a large portion of the revenue.’ With Dorado constantly striving to improve their online world for players, the ability to continually update was a big draw for them.

The world of online gaming better lends itself to strategy games. With Dotschuweit and Porsche already big fans, their goal was to create a game they wanted to play. Their business model is also better suited to online gaming than consoles. ‘It’s free to play, so we incentivise players to pay for extra features, which doesn’t work well on console.’ This is where the money comes from. Players pay to construct buildings or train their troops more quickly, giving them an advantage over the competition.

But Stillfront’s acquisition of Dorado meant it was decision time for Dotschuweit. He had to choose between keeping his comfortable job with Stillfront, or taking on a new challenge in the startup world. Living in China with his family at the time, the ramifications of that decision were huge. Porsche was already in Malta, incentivised by the Maltese government’s support of new businesses. In the end, Dotschuweit felt the opportunity to join forces was too great to pass up. He made the leap.

The Rise to Success

Money was key. Dotschuweit tells us, ‘We managed to secure quite a sizeable employment-based grant from Malta Enterprise for our company, which was of course a very nice plus. And Malta is a really nice place!’ The grant not only helped Dorado win over investors, but it reduced risk in an industry that’s infamous for its kill rate, both in-game and in real life. Suffice to say that coming out on top in the gaming world is not guaranteed.

Working in a start-up was also a change for Dotschuweit. Having previously worked for US tech giant IBM, he wanted to make a mark with this new venture. ‘You get to have a lot more impact. Your presence matters a lot more to a small business; it’s a lot more fun. You get to wear lots of hats and get a lot of experience.’ The busy and exciting nature of a small business appealed to him much more than clocking in to a regular office job.

The good times continued rolling with more support coming in from the University of Malta’s (UM) Centre for Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation (CEBI). CEBI houses the TAKEOFF programme which supports new businesses and provides facilities for them. Dr Joseph Bartolo and Prof. Russell Smith are familiar names when it comes to Maltese start-ups, and they have both been an influential part of Dorado’s story. They now operate from the TAKEOFF building on UM’s Msida campus.

But Dorado’s journey is not all smooth sailing. ‘We are a live service and we don’t have separate teams for operations and expansions, so that sometimes means your plans change!’ explains Dotschuweit. It’s all hands on deck to fix any problems. ‘It’s part of the bane and the fun of operations. But it doesn’t get boring!’ he says. This means that a day of meetings can quickly turn into a hectic day of making sure the game is running smoothly. They don’t want to disrupt players’ gameplay if they can avoid it.

In the past, Dorado hired game developers to bring their ideas to life. But this modus operandi changed when it came to Conflict of Nations. With this project, Dotschuweit and Porsche wanted more control, and they were ready to invest. They dug their heels in and hired their own team.

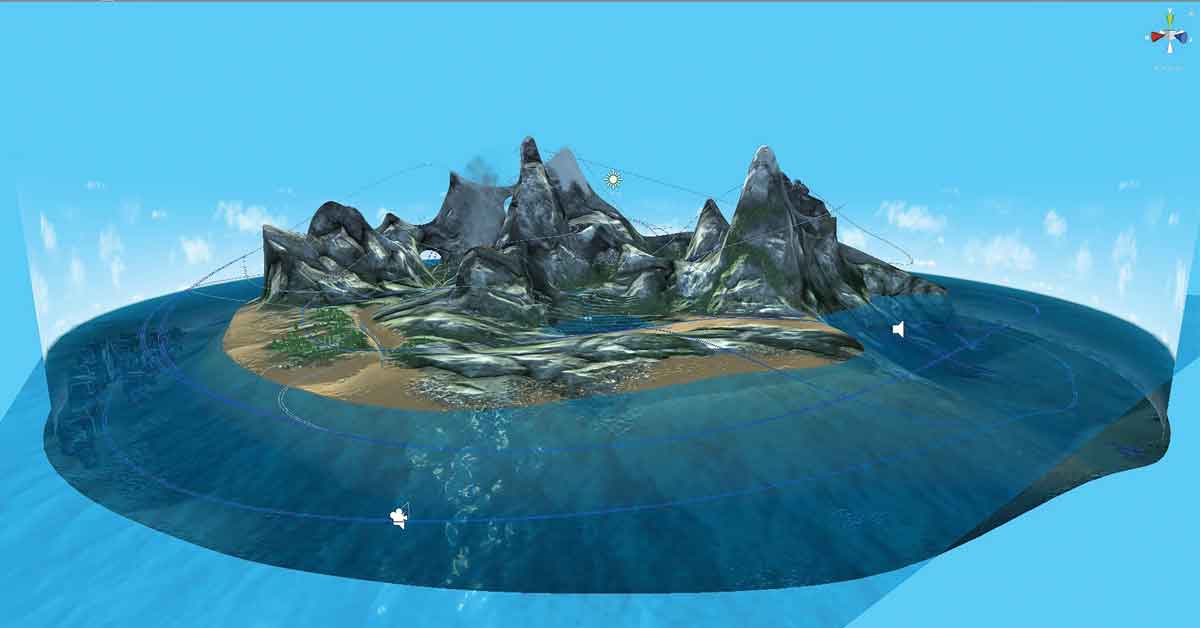

A game of political and military tactics with elements of espionage, Conflict of Nations requires real-world diplomacy skills to move up in the world. Unlike most other strategy games, it takes place right here on Earth, making use of Google Maps to make the game truly global.

Bringing their dream team to life was a challenge. ‘Finding talent back then wasn’t the easiest thing,’ says Dotschuweit. But their perseverance has seen them build a close-knit team who have all contributed to Dorado’s success.

The quest for perfection is a common theme in Dorado’s story. The perfect team, the perfect platform, the perfect game. Their commitment to giving players the best possible experience is a testament to their investment in their projects. Taking the time to get the right team together has proved to be one of the many reasons for Dorado’s fast climb up the games industry ladder. Another was getting their game out quickly to get fan feedback as soon as possible. The Stillfront platform restricts them somewhat in their design, as it wasn’t made specifically for Dorado, by Dorado, but it has reduced their workload massively, allowing them to get Conflict of Nations launch-ready in a fraction of the time. Identifying and taking advantage of opportunities has also been key to their quick rise.

Many Lessons Learnt

In the crowded world of online games, Dorado games has skillfully managed to carve out its place. Real-time negotiations and political tactics in Conflict of Nations are the stand-out features for fans who enjoy the long timescales and mental strategy involved. With this victory under their belt, we’ll soon see more from Dorado. They have plans to develop another game this year.

With years of experience in the industry, Dotschuweit has some advice for any future gaming entrepreneurs. ‘Get it out fast and get feedback. You can always improve it later.’ He notes the success of game jams in turning ideas into businesses and urges people to get involved. So, what are you waiting for?

Author: Dawn Gillies

Level up! Upgrading game-based learning

Suggesting a teacher might start the lesson by telling students to launch Pokémon-Go on their tablets might sound crazy, but this could be the new way to engage a generation of technophiles. Dr Vanessa Camilleri writes about the potential impact of gaming in the classroom.

Do you think this is a game?

Picture an item of furniture. Was it a table, a chair, or a wardrobe? Our ideas of furniture are not oriented around what it does, or even its essential nature, but rather around all the common examples we see around us and the cognitive web of interrelations that builds in our head.

This fictional furniture is just an analogy. Supervised by Prof. Gordon Calleja, I investigated how language affects our preconceptions of what games are and what they should do. Our ideas about games are not related to their potential or their openness but to constructions in our mind.

My research was mostly within the philosophy of language. I explored how our ideas of what a thing is are not grounded in what it does or is, but around a cognitive image, created by what we often see and label it as.

My research was mostly theoretical. It showed how other game researchers might have been misguided or had counter-intuitive results. Their research tried to define what games are and did not realise that this went against how we used the word ‘games’, i.e. as a container for all the things we collectively consider game-like.

That said, I also had the opportunity to test-drive this work in a game I am currently developing with Dr Stefano Gualeni, which analyses what the word soup means.

Apart from answering the long-standing question of what a game actually is, this research also shows how games would benefit from being more inclusive and experimental. By creating these types of games, we can attract people whose cognitive model of a game is different from the norm. Similarly, by designing games that are more open, we can stretch the web of interconnections in people’s minds, potentially showing how games are more akin to life than we realise.

Are you ready to play?

This research was carried out as part of the Masters in Digital Games, carried out by the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta.