Over half the global population now lives in cities. As the march of urbanisation trudges on, cities across the globe face mounting pressure to think of urban and green futures for communities in the face of the climate crisis.

But creating a plan for a sustainable future risks missing the green mark if citizens are not given a seat at the table to express their needs and desires, leading to a waste of resources or solutions that no one uses.

An ambitious EU project called VARCITIES is aiming to lead the way with tangible, nature-based solutions that put citizens at the forefront of greener future cities. At present, seven pilot cities (including one seaside locality in Malta, Gzira) are testing and implementing a series of these community-based actions for better creativity, inclusivity, health, and happiness for their citizens.

THINK caught up with two of the team members, Kurt Calleja and Emma Clarke, to talk about the project.

How it All Began

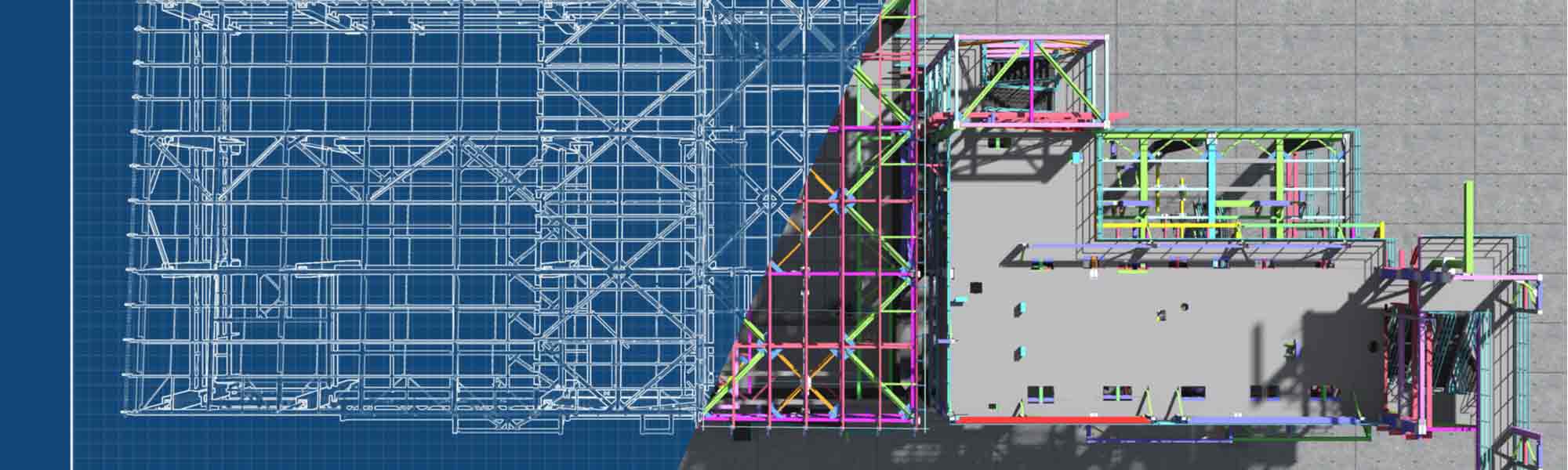

According to Calleja and Clarke, the key first step was to identify characteristics of the pilot sites, which in Malta was Gzira. Then, it became important to talk to various stakeholders: experts, the local council, and most importantly, the locals in order to map out the project’s blueprints.

‘Through this, we identified multiple benefits and how various groups stand to gain from the project. We then considered unforeseen outcomes for the project to try to be as realistic as possible,’ Calleja says.

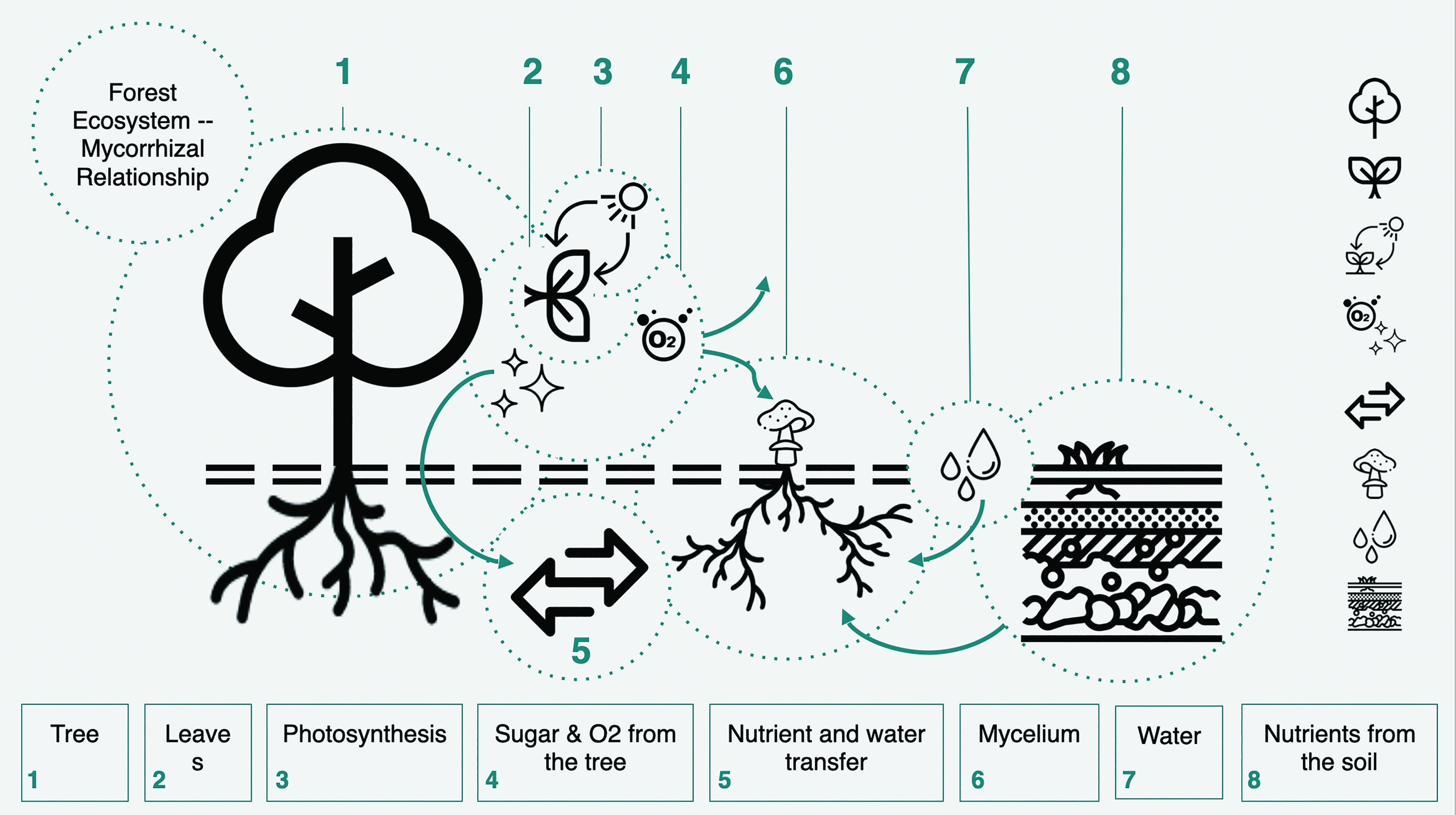

‘I say realistic because there are several misconceptions about environmental sustainability,’ he adds. ‘There is more to it than simply planting a few trees. The problem is far more complex and requires proper, long-term planning.’

In fact, a workshop held in June 2022 with local residents found that persistent frustrations included a severe lack of green open spaces, limited walkability because of narrow pavements, poor air and noise quality, and a need for more pedestrian routes.

How to Make a Greener, Meaner City

VARCITIES is trying to do a lot. Firstly, it wants to implement micro-greening interventions on a main artery of Gzira, Triq D’Argens, which currently does not have any sort of greenery and is rife with noise and exhaust pollution. This will be implemented through a participatory design process which includes residents, educators, creatives, and experts.

The project also focuses on urban diversity, education, and engagement through innovative pop-up parks and events. It wants to develop a co-created community garden project. The garden, Calleja explains, will be implemented in a collaborative way with artists such as Laura Besancon, an artist in playful interactions who has worked with the children of Gzira Primary School to design the playground.

‘The idea is not to just build a garden and leave it at that. We want to know what residents actually want, not just plant a few trees and build concrete structures,’ he continues.

In other words, they want to make sure it’s going to be used. Currently, the team has observed that playgrounds are not being used by people or children because they were not designed with the users in mind.

The ‘Human-Centred’ Approach to Design

For the playscape, the VARCITIES team organised workshops with school students, both to educate and as a form of data collection. The playscape is ‘human-centred’ but is also designed according to a need for better biodiversity in order to improve the ecosystem and attract more insects through greening.

In the first workshop with the school children, the team took an ethnographic approach through two parts: visual and experimental.

‘We invited children to go around school to capture photos of places that mean something to them. Then we moved to a more auditory-based practice: we asked the children to document the sound environment of their school, to really actively listen rather than just hear,’ Calleja says.

The soundscapes made by the children were unsurprising; they were sounds of constant traffic, construction, and some bird sounds.

‘Something that stuck out was that even though noise is a part of their everyday culture, it was still something very bothersome and disruptive for them,’ Clarke says.

‘Without any accessible greenery around, they feel disconnected from nature and gravitate more towards their phones,’ she adds.

In the following workshop, the children were asked to unleash their creativity. A blank canvas was laid out, and they were asked to design their ideal playground, a chance to brainstorm and think together on what a future part of their school could be. Now, their artworks are being used as inspiration for the final design of the playscape.

In one last intervention, the team held a planting and propagation workshop, and the plants they nurtured will be used in the actual garden. It’s a wholly collaborative and educative process. In addition to designing the playscape/community garden, the VARCITIES team have hosted a series of pop-up parks around Triq D’Argens throughout November. These parks provided space for social interactions as well as art and science installations, all done in collaboration with local business, citizens, artists and NGOs.

A Blueprint for Going Green Globally

Ultimately, the goal is to build more inclusive and greener cities, and city-based projects like this will let stakeholders evaluate how efficient and effective nature-based solutions are. Initiatives like VARCITIES that use bottom-up, citizen-oriented approaches could become models to build our future cities now.

‘We believe in using the bottom-up, citizen-oriented approach for sustainable solutions for cities. The idea is to eventually be able to see what works and what doesn’t, learn, and upscale the approach, to champion sustainable solutions and improve our lives,’ Calleja said.

Cities that cater for our needs and desires as citizens as well as change the course of climate disaster should not be a utopian fantasy. The interventions done in Gzira could be the green blueprints for everyone’s future.

VARCITIES is an H2020 funded EU project (grant agreement: grant agreement No 869505) led in Malta by Dr Ing. Daniel Micallef (Faculty for the Built Environment) who is supported by academics in the Faculty of Education, Faculty of Science, and Faculty of Engineering including: Dr Edward Duca, Antoine Gatt, Carlos Canas, Dr David Paul Suda, Prof. Emmanuel Singara, Dr Kenneth Scerri, Dr Sarah Scheiber, Dr Simon Borg, Prof. Vincent Buhagiar, and Dr Mark Caruana.

This project is supported by Arts Council Malta.