‘In Search of Line’ is a thought-provoking exhibition that delves into the role of the line in art, offering a deep exploration of how artists use the line to convey images, meanings, and emotions. The collection features a diverse mix of local and international artists, spanning from prehistoric works to modern creations. Prof. Vince Briffa’s unique essays add depth to the experience, reflecting on select pieces from a philosophical and personal perspective.

Continue readingSchizophrenia and Art

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder that affects reality perception, but studies suggest that individuals with it tend to have superior creative skills. Art therapy is used to address negative aspects of the disorder and may help diagnose it. Art can serve as an outlet to express what cannot be described in words, and its content can vary significantly between those with the disorder and healthy individuals.

Continue readingModern Fashion from Ancient Pottery

How historic pottery sherds outlived their makers and inspired a contemporary artist.

Continue readingAristotle’s Nymphomaniac Ethics

The first in our new THINK Oddities series, where we take a look at the many odd things that dot history! And what better way to start than with the story of Aristotle playing sub?

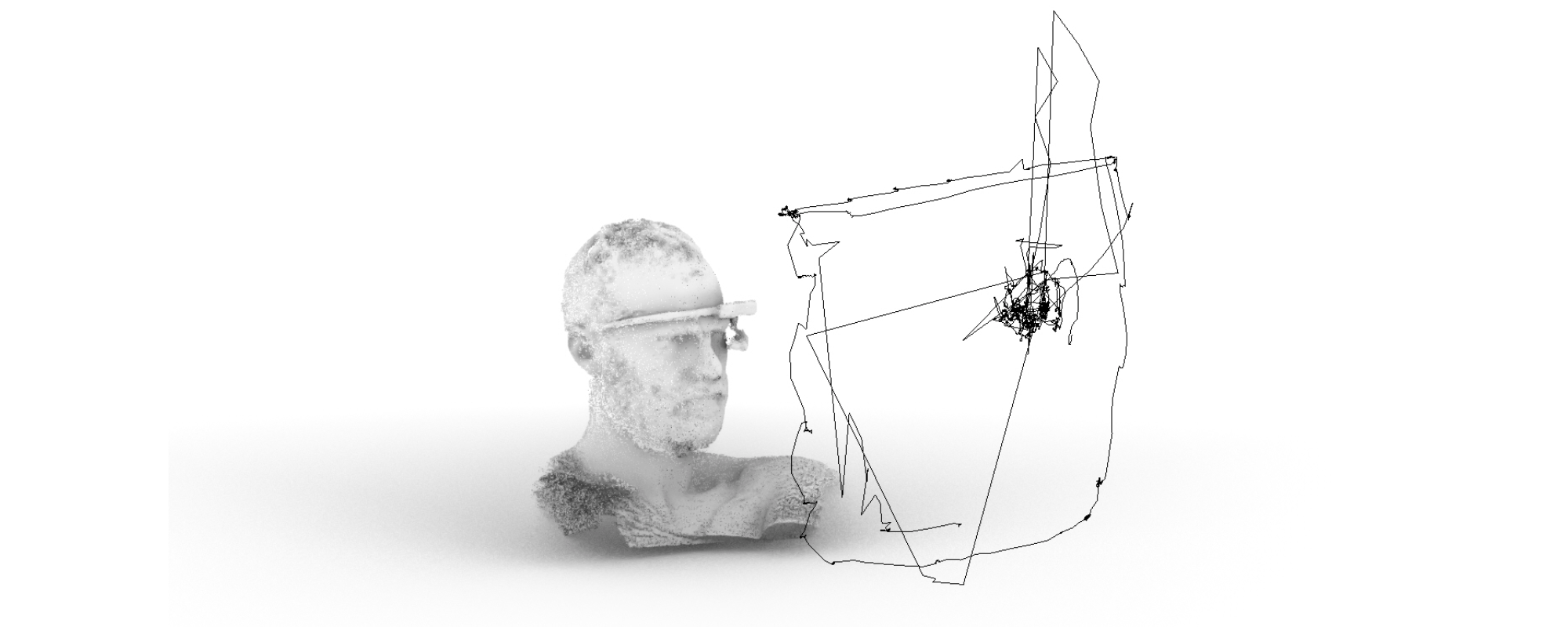

Continue readingDrawing with Data

Artist Matthew Attard uses eye-tracking to spark intriguing conversations, challenging us to see the world through new eyes and explore the intersection of art and activism.

Continue readingWill NFTs live up to their potential?

You might have stumbled across the phrase ‘NFT’, but what on earth are they? THINK takes a look at NFTs, where they came from, and what they’re all about.

Continue readingSuch Stuff as Worlds are Made On

What would remain of our once-great civilization if humanity went extinct? Such Stuff as Worlds are Made On explores these themes at Spazju Kreattiv.

Continue readingUncovering history

Commissioned over half a millennium ago, Antonello Gagini’s Madonna and Child has been silently standing tall in a Franciscan church in Rabat for the past five centuries. Little was known about the Renaissance sculpture, but a recent study is tracing the statue’s history. Caroline Curmi speaks to art historian Dr Charlene Vella and University of Malta student Jamie Farrugia about their findings.

Continue readingCreativity in a concrete jungle

Surrounded by ever-changing environments, it is crucial to take the time to pause and reflect. That’s exactly what Maltese-French artist Laura Besançon does in her exhibition Playful Futures — and she’s inviting you to play along. The exhibition attempts to refresh our perspectives on the changing contexts that are beyond our control.

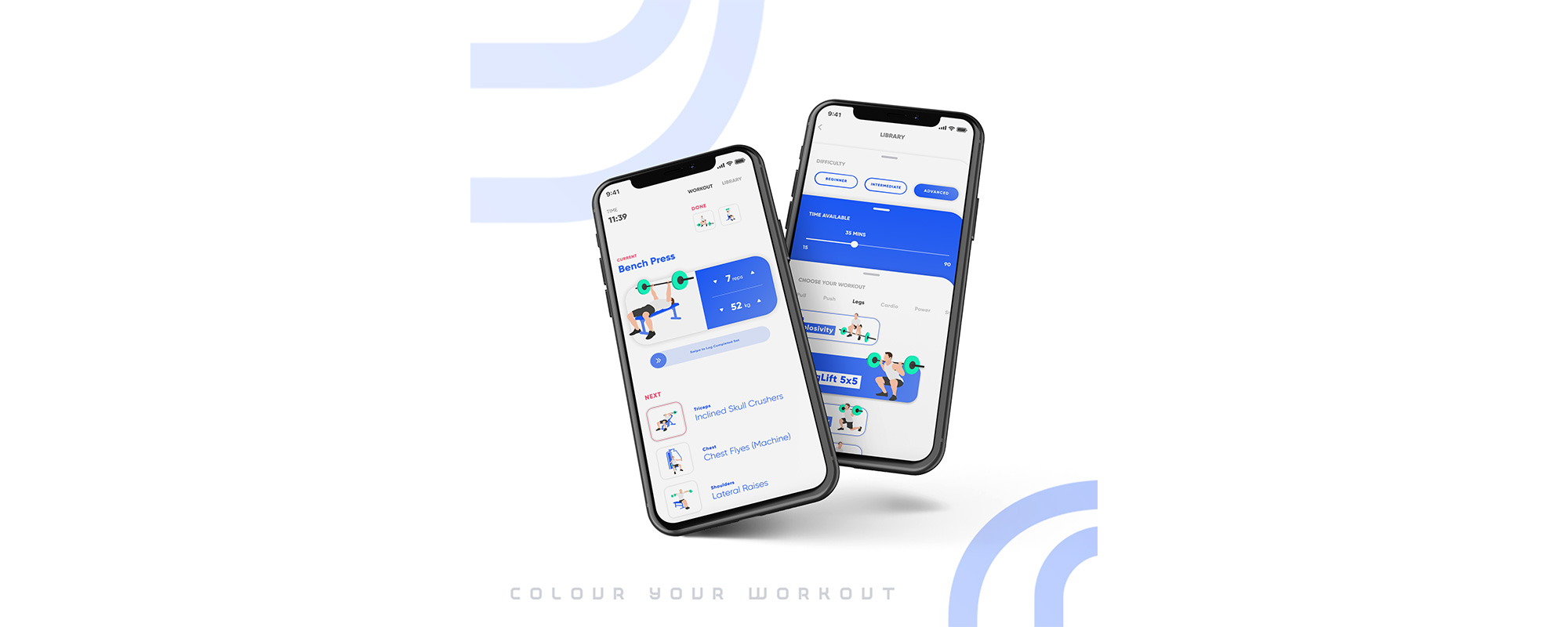

Continue readingThe pandemic did not ‘undo’ our exhibition

As 35 University of Malta students prepared to showcase their dissertation projects in an exhibition at Junior College, restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19 turned their plans upside down overnight. Yet the exhibition, titled Ctrl Z, is still taking place, having moved to where people are – online.

Continue reading