How much do you know about the history of THINK? If you’re a THINK superfan, then you know that the first edition wasn’t called THINK. Read on to learn more about how THINK evolved over the last decade.

Continue readingBHums: The Degree for Free Spirits

A free spirit should not be bound to the confines of one academic discipline. With its focus on human experiences, interdisciplinary approaches, critical thinking, and creativity, the BHums will certainly satisfy your voracious intellectual appetite.

Continue readingHelp Monitor the Buzz – Join the Malta Pollinator Monitoring Scheme

Calling all nature enthusiasts. Are you alarmed by the rapid decline of critters which pollinate our plants? Do you want to have a positive impact on the world around you? Then consider signing up to become a citizen scientist in the Malta Pollinator Monitoring Scheme (MPOMS) today!

Continue readingThe unusual suspects

When it comes to technology’s advances, it has always been said that creative tasks will remain out of their reach. Jasper Schellekens writes about one team’s efforts to build a game that proves that notion wrong.

The murder mystery plot is a classic in video games; take Grim Fandango, L.A. Noire, and the epic Witcher III. But as fun as they are, they do have a downside to them—they don’t often offer much replayability. Once you find out the butler did it, there isn’t much point in playing again. However, a team of academics and game designers are joining forces to pair open data with computer generated content to create a game that gives players a new mystery to solve every time they play.

The University of Malta’s Dr Antonios Liapis and New York University’s Michael Cerny Green, Gabriella A. B. Barros, and Julian Togelius want to break new ground by using artificial intelligence (AI) for content creation.

They’re handing the design job over to an algorithm. The result is a game in which all characters, places, and items are generated using open data, making every play session, every murder mystery, unique. That game is DATA Agent.

Gameplay vs Technical Innovation

AI often only enters the conversation in the form of expletives, when people play games such as FIFA and players on their virtual team don’t make the right turn, or when there is a glitch in a first-person shooter like Call of Duty. But the potential applications of AI in games are far greater than merely making objects and characters move through the game world realistically. AI can also be used to create unique content—they can be creative.

While creating content this way is nothing new, the focus on using AI has typically been purely algorithmic, with content being generated through computational procedures. No Man’s Sky, a space exploration game that took the world (and crowdfunding platforms) by storm in 2015, generated a lot of hype around its use of computational procedures to create varied and different content for each player. The makers of No Man’s Sky promised their players galaxies to explore, but enthusiasm waned in part due to the monotonous game play. DATA Agent learnt from this example. The game instead taps into existing information available online from Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons, and Google Street View and uses that to create a whole new experience.

Data: the Robot’s Muse

A human designer draws on their experiences for inspiration. But what are experiences if not subjectively recorded data on the unreliable wetware that is the human brain? Similarly, a large quantity of freely available data can be used as a stand-in for human experience to ‘inspire’ a game’s creation.

According to a report by UK non-profit Nesta, machines will struggle with creative tasks. But researchers in creative computing want AI to create as well as humans can.

However, before we grab our pitchforks and run AI out of town, it must be said that games using online data sources are often rather unplayable. Creating content from unrefined data can lead to absurd and offensive gameplay situations. Angelina, a game-making AI created by Mike Cook at Falmouth University created A Rogue Dream. This game uses Google Autocomplete functions to name the player’s abilities, enemies, and healing items based on an initial prompt by the player. Problems occasionally arose as nationalities and gender became linked to racial slurs and dangerous stereotypes. Apparently there are awful people influencing autocomplete results on the internet.

DATA Agent uses backstory to mitigate problems arising from absurd results. A revised user interface also makes playing the game more intuitive and less like poring over musty old data sheets.

So what is it really?

In DATA Agent, you are a detective tasked with finding a time-traveling murderer now masquerading as a historical figure. DATA Agent creates a murder victim based on a person’s name and builds the victim’s character and story using data from their Wikipedia article.

This makes the backstory a central aspect to the game. It is carefully crafted to explain the context of the links between the entities found by the algorithm. Firstly, it serves to explain expected inconsistencies. Some characters’ lives did not historically overlap, but they are still grouped together as characters in the game. It also clarifies that the murderer is not a real person but rather a nefarious doppelganger. After all, it would be a bit absurd to have Albert Einstein be a witness to Attila the Hun’s murder. Also, casting a beloved figure as a killer could influence the game’s enjoyment and start riots. Not to mention that some of the people on Wikipedia are still alive, and no university could afford the inevitable avalanche of legal battles.

Rather than increase the algorithm’s complexity to identify all backstory problems, the game instead makes the issues part of the narrative. In the game’s universe, criminals travel back in time to murder famous people. This murder shatters the existing timeline, causing temporal inconsistencies: that’s why Einstein and Attila the Hun can exist simultaneously. An agent of DATA is sent back in time to find the killer, but time travel scrambles the information they receive, and they can only provide the player with the suspect’s details. The player then needs to gather intel and clues from other non-player characters, objects, and locations to try and identify the culprit, now masquerading as one of the suspects. The murderer, who, like the DATA Agent, is from an alternate timeline, also has incomplete information about the person they are impersonating and will need to improvise answers. If the player catches the suspect in a lie, they can identify the murderous, time-traveling doppelganger and solve the mystery!

De-mystifying the Mystery

The murder mystery starts where murder mysteries always do, with a murder. And that starts with identifying the victim. The victim’s name becomes the seed for the rest of the characters, places, and items. Suspects are chosen based on their links to the victim and must always share a common characteristic. For example, Britney Spears and Diana Ross are both classified as ‘singer’ in the data used. The algorithm searches for people with links to the victim and turns them into suspects.

But a good murder-mystery needs more than just suspects and a victim. As Sherlock Holmes says, a good investigation is ‘founded upon the observation of trifles.’ So the story must also have locations to explore, objects to investigate for clues, and people to interrogate. These are the game’s ‘trifles’ and that’s why the algorithm also searches for related articles for each suspect. The related articles about places are converted into locations in the game, and the related articles about people are converted into NPCs. Everything else is made into game items.

The Case of Britney Spears

This results in games like “The Case of Britney Spears” with Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross, and Taylor Hicks as the suspects. In the case of Britney Spears, the player could interact with NPCs such as Whitney Houston, Jamie Lynn Spears, and Katy Perry. They could also travel from McComb in Mississippi to New York City. As they work their way through the game, they would uncover that the evil time-traveling doppelganger had taken the place of the greatest diva of them all: Diana Ross.

Oops, I learned it again

DATA Agent goes beyond refining the technical aspects of organising data and gameplay. In the age where so much freely available information is ignored because it is presented in an inaccessible or boring format, data games could be game-changing (pun intended).

In 1985, Broderbund released their game Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, where the player tracked criminal henchmen and eventually mastermind Carmen Sandiego herself by following geographical trivia clues. It was a surprise hit, becoming Broderbund’s third best-selling Commodore game as of late 1987. It had tapped into an unanticipated market, becoming an educational staple in many North American schools.

Facts may have lost some of their lustre since the rise of fake news, but games like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? are proof that learning doesn’t have to be boring. And this is where products such as DATA Agent could thrive. After all, the game uses real data and actual facts about the victims and suspects. The player’s main goal is to catch the doppelganger’s mistake in their recounting of facts, requiring careful attention. The kind of attention you may not have when reading a textbook. This type of increased engagement with material has been linked to improving information retention.In the end, when you’ve traveled through the game’s various locations, found a number of items related to the murder victim, and uncovered the time-travelling murderer, you’ll hardy be aware that you’ve been taught.

‘Education never ends, Watson. It is a series of lessons, with the greatest for the last.’ – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, His Last Bow.

Home

Author: Dr Pat Bonello

The theme of this edition of THINK magazine is meant to evoke feelings of belongingness, identity, warmth, and solidarity. Our home is usually a place associated with these positive feelings: a place where I can be myself and, in a safe environment, develop into the me I want to be. This is something valuable, something which we should safeguard passionately. At the same time, as a social worker, I know many people for whom ‘home’ does not have such positive connotations.

The people that come to mind are abuse victims, children and adults living with domestic violence. For them, ‘home’ means suffering, often accompanied by a feeling of helplessness. Others find ‘home’ a difficult concept. Think of people who cannot make ends meet, who have difficulty paying their rent, who cannot afford to buy their own house because of high property prices. Then there are those who can no longer live in their own house because they are unable to look after themselves, be it because of old age or health issues. There are members of broken families who have difficulty identifying their home, asylum seekers who left home behind, and people who have lost a family member and now associate ‘home’ with sadness.

Everybody needs a place where he or she feels ‘held’ and safe enough to develop his or her potential. But if ‘home’ does not fit this bill, where will this environment be?

This is where a network of social solidarity, both formal and informal, comes into play. Alternatives for people with issues related to the concept of ‘home’ include foster placements, shelters, or other residential facilities. But these services are tasked with much more than providing mere accommodation. They need to create an environment which meets the needs of the persons who live there. They need to provide a safe space for people to come in, be themselves, and develop their potential.

For those who don’t need to move out of their current home, options include support and professional interventions, such as family therapy, to deal with the sadness associated around the home, or to improve the dynamics within it. Social service providers in Malta and Gozo carry a lot of responsibility. Unfortunately, the supply does not always meet demand, and some people have to wait considerably before being able to move into more comfortable and nurturing placements—sometimes while living in abusive environments. In other situations, the necessary support is not readily available, as in the cases of asylum seekers and homeless people who need a roof over their head.

While formal support is important and necessary, all Maltese citizens need to share the responsibility and offer a helping hand without judgement. That way, Malta will be able to nurture communities that work together to create ‘homes’ which cherish everyone, respecting their dignity and worth and encouraging them to flourish.

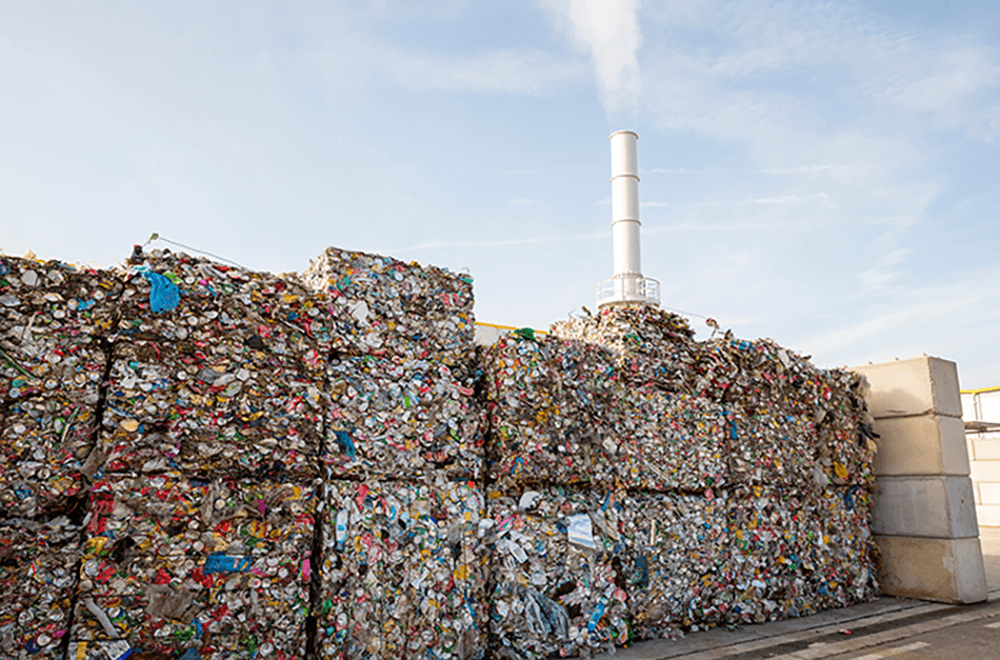

Waste’s carbon footprint

When people think about the impact waste has on our environment, they usually think about toxic materials in landfills, the land they take up, and the animals harmed by irresponsible waste disposal. But there is more. Our garbage also contributes to greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere.

Continue readingProtecting prisoners from radicalisation

Curbing extremism and violence is high on the global agenda. With prisons known to be a breeding ground for recruiters, are we doing enough to protect our inmates? Michela Scalpello writes.

Continue readingPolicing the seas

Living on an island in the middle of the Mediterranean, chances are that fish are an integral part of your diet. But do you think about how the fishing industry actually works? Kirsty Callan talks to Dawn Borg Costanzi about the need for safer, more ethical practices.

Continue readingBursting the RRI bubble

Relationships are based on trust, communication, and mutual respect. The same can be said of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI). Behind all the new ideas, it all boils down to a group of people, hailing from different walks of life, coming together to try and create a better future for everyone. At the fourth annual NUCLEUS conference, researchers, academics, science communicators, creatives, and business people flocked to the tiny isle of Malta to share their stories and attempts to embed RRI into their institutions and communities. As everyone settled in, dialogue flowed among delegates and the room was abuzz. University of Malta pro-rector Prof. Godfrey Baldacchino opened the conference with a question: How similar are universities and Valletta, the fortified capital that was hosting the conference? Having been constructed following Malta’s infamous Great Siege, the Knights encased Valletta in massive bastions, allowing only four small entry points. ‘Valletta is an island on an island,’ Baldacchino said. ‘Are universities the same? Are we trying to protect our own?’ The question had many heads nodding in response.

Most people in the room expressed a feeling of obligation to render knowledge more accessible, more relevant, and more digestible to a wider audience. But they encounter a myriad of challenges. Engaging with publics or policy makers isn’t easy. It means addressing different needs in different ways, sometimes even pandering to whims and flights of fancy. Most people noted issues with time, funding, and resources, calling for processes to be formalised. Others pointed to a lack of creative skills and, sometimes, general interest across the board. What also quickly emerged was frustration with the term RRI itself, creating confusion where there needn’t be any.

With all of these difficulties, however, came solutions. Dr Penny Haworth from the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, said that in her experience ‘we need to look at what universities are already doing and work smart. Win hearts and minds.’ University of Malta’s Nika Levikov also pointed out that ‘there are a lot of people practicing RRI who are not conscious of it.’ And for those who do not believe it to be a priority, for those who do not want to engage? ‘You have to set them aside and show them it is possible in a way they understand,’ says Zoran Marković from MISANU, Serbia.

Picking up Baldacchino’s thread on bringing down the walls of universities and research institutions, Dr Annette Klinkert from Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences in Germany summed up her main takeaway from all the discussions. ‘What we can learn here is that it’s time to burst the bubble in which we work. Especially this field of RRI. It is time to leave our cosy little community with our results.’ The results are the various projects that NUCLEUS has been championing over the past years, bringing research to its audiences. ‘All the projects are useless if they can’t merge and get out [into society and communities],’ she emphasises. ‘If they don’t merge, they’re pointless. It is time to burst the bubble.’

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Food, gender and climate change

Food is one of life’s constants. Yet, what we eat has major ramifications on global climate. Food production uses up major resources: it accounts for more than 70% of total freshwater use, over one-third of land use, and accounts for just shy of 25% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, of which 80% is livestock. Yes, that steak you just ate has had a direct impact on the world’s climate! There is something of an oxymoron in the world’s food ecosystems. Overconsumption is linked to major health problems like obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers that together account for up to 71% of global deaths. On the other hand, there are around one billion people in the world who suffer from hunger and underconsumption. All of this is compounded by problems of food loss and waste. This raises important questions related to the ethics of worldwide food production and distribution.

Food production and consumption is determined by many factors: population numbers, incomes, globalisation, sex (biology), and gender (socio-cultural) differences. The combination of a sedentary lifestyle and an unbalanced diet, high in red, processed meat, low in fruits and vegetables, is a common problem in many developed countries. And this impacts not just human health, but also biodiversity and ecosystems.

Supervised by Prof Simone Borg, I chose an exploratory research design with embedded case studies. The aim was to analyse the dietary patterns of men and women. I wanted to critically question the power relations that feed into socio-economic inequities and lead to particular food choices. I used both quantitative and qualitative methods, modelling the life cycle assessment and scenario emission projections for 2050 in Malta, Brazil, Australia, India, and Zambia among males and females aged 16 to 64.

The four dietary scenarios I took into consideration were present-day consumption patterns (referring to the 2005/7 Food and Agriculture reference scenario), the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended diet (300g of meat per week and five portions per day of fruit and veg), vegetarian/mediterranean/pescatarian diets, and the vegan diet. From there, I measured ammonia emissions, land use, and water from cradle to farm gate, with a special focus on gender.

The findings were alarming, indicating that none of the five countries are able to meet emissions reductions under current dietary patterns. If we were to adopt the WHO recommended diet, GHGEs would be cut by 31.2%. A better result would be gained from a vegetarian diet, which would slash emissions by 66%, while a vegan diet comes out on top with a projected 74% reduction.

Some interesting points that arose were that the Global Warming Potential is higher in men in all countries due to higher meat consumption. Zambia and India would benefit the most from the proposed dietary shifts in absolute terms, while Australia, Malta, and Brazil would feel the positive impacts on individual levels in per capita terms, reducing carbon footprints considerably.

Reduced meat consumption substantially lowers dietary GHG emissions. We need to prospectively consider the interplay of sex and gender, and develop climate change, health, and microeconomic policies for effective intervention and sustainable diets. Adopting a flexitarian diet that is mostly fruits and vegetables, with the occasional consumption of meat, can save lives, the planet, and economies—some food for thought!

This research was carried out as part of a Master of Science (Research) in Climate Change and Sustainable Development at the Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, University of Malta.

Author: Precious Shola Mwamulima