Filling in an FS3 form (Statement of Earnings/Tax Return forms) is already a headache, but imagine trying to prepare accounts for a small business. It is a time-consuming and laborious process, and doing things by hand can lead to serious mistakes. Why haven’t we automated accounting yet?

Continue readingAI Meets the Maltese Courts: Can AI Simplify Small Claims Proceedings?

The idea behind the AMPS project is to investigate the use of natural language processing and machine learning to predict the outcome of Maltese court cases, specifically those within the Small Claims Tribunal, which deals with claims of up to €5000. The objective is to provide a tool to help adjudicators decide cases more efficiently while respecting and integrating the ethical and safety concerns which inevitably arise. By aligning with best practices and guidelines, the project team intends not only to develop a tool for the courts but also to advance the use of the Maltese language in relation to Artificial Intelligence (AI).

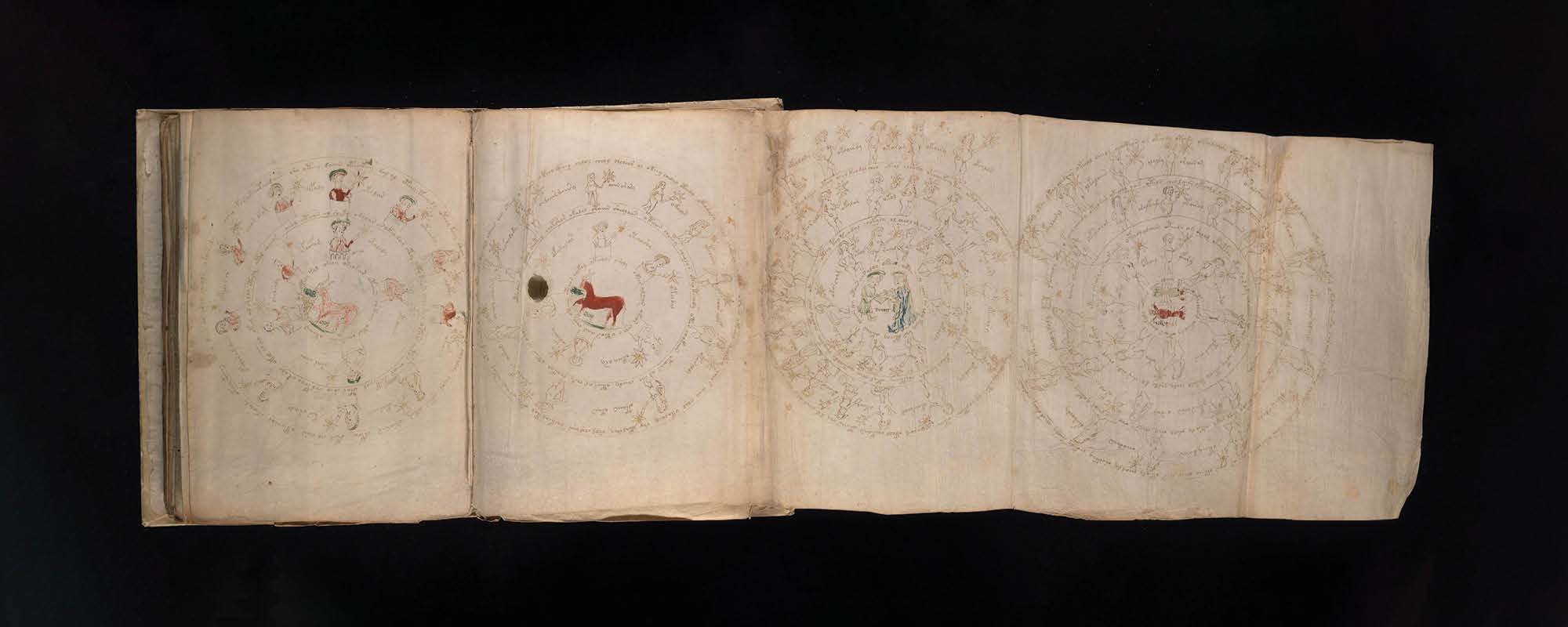

Continue readingThe Voynich Manuscript

The Voynich Manuscript is one of the most enduring historical enigmas, attracting multidisciplinary interest from around the world. Jonathan Firbank speaks with UM’s wing of the Voynich Research Group about the history, mystery, and cutting-edge technology brought together by this unique medieval text.

Continue readingTweeting About the News

Nicholas Mamo has developed an algorithm that analyses Twitter feeds and extracts information about events. This type of artificial intelligence has been designed to automatically identify the participants involved in the events and understand what happened based on the tweets.

Continue readingSmartAP: Assisting Pilots with AI

As passengers, we often overlook the complexity and challenges faced by pilots as they navigate the skies. THINK explores SmartAP, a cutting-edge AI technology that could help pilots combat stalling and difficult landing situations. Buckle up, sit back, and enjoy the journey!

Continue readingModl.ai: Creating the Ultimate AI Game Testers

A spin-out from the University of Malta’s Institute of Digital Games is working on artificial intelligence-run game testing software. The engine would run thousands of low-level testing rounds before humans engage in high-level testing of a game prior to market release. Modl.ai co-founder Georgios N. Yannakakis tells THINK how his team aspires to change the game.

Continue readingIs ChatGPT an Aid or a Cheat?

From the perspective of a student and an academic, how can ChatGPT be used in academia? Nathanael Schembri explores how the AI could be used to aid in assessments as well as scholarly work; such as in writing dissertations and research papers.

Continue readingLet’s Have a Chat about ChatGPT

ChatGPT has taken the world by storm since its launch in November 2022. It is a chatbot developed by OpenAI and built on the GPT-3 language model. What sets it apart from other AI chatbots is the sheer amount of data it has been trained on, allowing the quality of its responses to cause waves, leading to headlines such as ChatGPT passing key professional exams. It has also consequently caused concern in academia that it may be used to cheat at exams and assignments. We speak to two academics from the University of Malta, Dr Claudia Borg and Dr Konstantinos Makantasis, to see how academia should adapt. Are such advances a threat to be curbed or an opportunity to be exploited?

Continue readingDigitising Health

Medical diagnosis relies on data. A physician observes and analyzes a patient’s vital signals to assess their condition and prescribe adequate treatment. The more accurate and reliable the data, the better the treatment. Through the use of technology, digital health allows both physicians and patients real-time access to medical data.

Continue readingJuggling Jellyfish: How AI can improve citizen science projects

One of the largest citizen science projects in Malta, Spot the Jellyfish has helped record many interesting discoveries about marine life. But as the project grows, the team must expand their technology to cope with the influx of data. Prof. Alan Deidun, Prof. John Abela, and Dr Adam Gauci speak to Becky Catrin Jones about their latest developments.

Continue reading