Prof. Patrick J. Schembri lives for biology. His long career has brought him in touch with an endless list of creatures that includes fish, beautiful white coral, sharks, limpets, crabs, and ancient snails. Edward Duca met up with Schembri to find out more about the life around Malta.

I was nervous. I still remembered fumbling for excuses for handing in my assignment a few days late. Prof. Patrick J. Schembri’s stern gaze does not take excuses. This time I entered his office to learn about the wealth of research under this man’s belt. With over 150 refereed papers to his name I knew I would not leave disappointed.

In 1982 Schembri returned to Malta after a doctorate at the University of Glasgow and a post-doctorate in New Zealand.

‘In Scotland, I was working on animals that came from a depth of 40m and in New Zealand with animals that came from the whole span of the continental shelf and upper continental slope at depths down to about 900m. For that you need a research vessel, crew, collecting equipment, and so on. I came to Malta and there was nothing’, said Schembri. This did not stop him, like the animals he studies, he just adapted.

‘Nobody has looked at the ecology of shores in Malta before, so I decided to do that.’ And as simple as that, Schembri went from studying deep water animals to the near shore. The techniques and equipment needed are completely different — a diverse research background that must have helped him in his long career. After many years, Schembri returned to studying life in deep waters, invasive species, and many other things, but more on that later.

Back in the 80s the Internet simply did not exist locally so Schembri’s biggest problem was not equipment but sourcing academic journals. Every scientist needs to constantly read journals to keep up to date with the latest findings. It is essential for research inspiration, to see knowledge gaps that can be studied, to learn new techniques and knowledge, and to avoid repeating others’ research. Schembri, ever determined, went to great lengths to get the information he needed in order to research and publish.

‘Thanks to my mentors I was brought up with a culture of publishing.’ The renown of every scientist depends on the importance of the journals they publish in and how much they publish. Neither was a problem for Schembri. ‘I produced my first paper before I did my A levels. In the early 1970s, I improvised some apparatus to do experiments on something that you would [normally] need sophisticated equipment for, so rather than using a nitrogen chamber, I used a plastic bag to which I attached kitchen gloves, and it worked.’ After some encouragement from his tutor the paper was written as a note that was published in School Science Review. He also published around six papers from his Master’s degree. No small feat, I have not achieved this even after a Master’s degree and a Doctorate.

A Master of all Trades

The breath of his studies is stunning. With his students, Schembri has studied animals which have invaded Maltese waters. These include the nimble spray crab (Percnon gibbesi) and the non-indigenous Red Sea mussel (Brachidontes pharaonis), which, unlike all native mussels is forming mussel beds with thousands of individuals. He has studied the seabed’s ecosystems that happen to be vital to maintain fish stocks. He has even delved into Malta’s ecological past analysing samples from cores drilled in Malta’s coastal sediments studying sub-fossil molluscs to piece together the Island’s early history. These were only possible through collaboration with many scientists and a vast army of students.

Percnon gibbesi

Photo by divemecressi, flickr

His collaborations have been essential. Schembri was contacted by Italian researcher Dr Marco Taviani to survey Malta’s deep seas. Taviani has access to the multi-million research vessel Urania. The 61.3m ship has on-board laboratories for geological, chemical, radiological, geophysical, and biological research. To make it in Malta, ‘if you don’t have enough resources you have to improvise and collaborate, especially with overseas researchers who do have the resources. And it worked’.

Schembri has gone further than just making it work. He has flourished. His strategy involves participating in EU funded projects (to bring in the money) while keeping very ambitious long-term projects running in the background on a shoestring. The only problem is that for ‘all the EU projects, the agenda is set internationally. While [for local projects] the funds are minimal, I get a few hundreds a year. But I am free to study what is interesting and important for Malta.’

Managing Fish

BENESPEFISH is one of his locally funded projects. ‘I want to find out what kind of habitats we (Malta) have and how fish interact with them.’ By studying what fish eat and where that food grows, by seeing the nursery grounds and spawning areas of the fish, by researching how the impact of fishing techniques affects the sea floor that ends up damaging the ecosystem. For example, in collaboration with the Government’s Fisheries Agency, students under Schembri’s supervision studied the effect of a type of fishing technique called otter trawling. They discovered that it can adversely change the benthic (seabed) ecosystem and that the trawling should be done in corridors, with spaces between them to allow the recuperation of the seabed, and therefore the dependent fish stocks. This will help fish stocks recuperate and fishermen to retain their livelihood.

“For some strange reason, beforehand fish were one thing and the rest of the sea was something else”

The above is called the ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Back in the early 2000s ‘Matthew Camilleri from the Fisheries and Aquacultures Department got involved in a FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) project called MEDSUDMED,’ that was pushing for this approach. ‘So he asked if I could help out with the ecological aspect. […] Ecologists entered the picture because in this approach fish started being looked at as part of the ecosystem. For some strange reason, previously fish were one thing and the rest of the sea was something else’ — a clear reason for fisheries scientists and marine biologists to work together to be able to give the right scientific advice to the Government.

The BENESPEFISH project hinges on a healthy relationship with the Government. The Government Fisheries Agency commissions the MEDITS trawl survey to monitor the health of fish stocks, which are mandatory for all EU member states that border the Mediterranean. These surveys need to ‘follow a strict protocol’, perfect for science. However, the survey ‘is limited to about 40 species. They still get everything else such as benthic organisms [that live on the sea bed] that they used to just throw overboard. So I said to them, okay why don’t you keep it, give it to me, I work on it, then I give you the results. […] If I had to hire a fishing trawler and go out myself for 14 days it would cost me around €190,000, crews and everything. Instead, by collaborating, we get this data at a low cost. All I need to pay for is for insurance, fixatives, sample containers, and a research assistant to collect the samples. So that’s what the University funds, it funds the research assistant and materials. […] So you [the Government] get information which you would not normally get because you are not a research institution.’ Clever and it worked.

These discards are valuable to find out about the ecology of the fish in our seas. ‘They were going to get rid of a few hundred sharks (the small-spotted catshark, Scyliorhinus canicula) […], so I got them and one of my students analysed their stomach contents which told us a great deal about what the fish feed on and also where they feed. […] They feed on fish but also on the benthos, the bottom material.’ From 532 stomachs sampled, over half were eating teleosts (a group of bony fishes) and nearly one fifth were eating crustaceans, with even some cannibalism. Male and female catsharks had different diets. To keep catshark populations healthy these food sources need to be maintained. The seabed is vital.

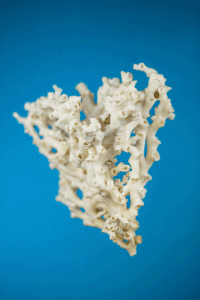

These MEDITS surveys have led to some surprising discoveries. During a survey one of Schembri’s students picked up a piece of white coral which she brought back to be identified in the lab. It turned out to be the deep water coral Lophelia pertusa that builds reefs. Schembri still had this piece and showed it to me. As I picked up this brilliant white coral he told me, ‘this is just a piece of a much larger structure. You can see the remains of some the individual animals [it is a colonial species made of many individuals], the cup-like structures with grooves.’ It is such a different species — out of this world. Schembri and his group reported finding this coral around Malta that attracted Marco Taviani (Institute of Marine Sciences, National Research Council of Italy), who was a colleague of Schembri, to organise a research cruise. Using the Italian research vessel the Urania they explored Maltese deep waters. This was the first of three such cruises that Schembri’s research group were invited to participate in. During one of these cruises they found other species of corals including the endangered red coral (Corallium rubrum), exploited since antiquity to make jewellery. They saw it at depths never seen before, around 600–800m, which is two to three times deeper than previously. When studied, this deep water population was found to be genetically isolated from others, probably because the different populations were not breeding amongst each other.

Malta’s Coast

When Schembri first came back to Malta he started working on its shores. But our coasts are not just beaches and cliffs. ‘Inland the coastal area extends as far as sea spray carries, since this renders the soil saline and therefore only adapted plants can thrive. […] Offshore, the coastal area extends to depths of 150–200m as material from the land, like sediment, still finds its way to the seabed even at those depths.’ That is a huge area for a researcher to cover, but Schembri wants to record all its habitats, obviously with a lot of help.

Enter the project Faunistics and Ecology of the Maltese Islands (FEMI), ‘the aim is to have an inventory of what we’ve got. […] I want to understand what habitats we have and which species live there.’ To cope with such a massive project, Schembri splits it up into bite-size research questions that his students can tackle over a few months (or longer if it is a Master’s or a Doctorate project). ‘The results of each small project contribute to the whole. […] By now I would say that over the years the number of people who have contributed to the project must be at least a hundred, although it is usually around six at any one time.’ Many of these student projects lead to research publications coming out from the University of Malta’s Department of Biology.

One of the most important things for the FEMI project is to figure out the state of our current environment. By knowing how things are we can tell how they are altered by future change. Back in 1998 Schembri, Dr Mark Dimech and Dr Joseph A. Borg studied how fish farms in St Paul’s Bay were affecting the ecosystem underneath. The nutrients and waste were reducing the biodiversity immediately under the cages to around a range of 30m. In between 50–170m, the fish farm unexpectedly increased the number and diversity of invertebrates. Without knowing the species normally growing in sea grass meadows this would be impossible.

By studying Malta’s coast and offshore waters for so long, Schembri can say which areas and habitats around Malta have the greatest diversity in species and which are at risk. These tend to overlap; on land the sand dunes and saline marshlands need to be preserved, while at sea it is the seagrass beds, maerl and other rhodolith bottoms, and any form of natural reef that need conservation. Such long term studies are essential to know how humans are impacting the environment and to better manage Malta’s living resources.

A Warming Mediterranean

The world is changing. The actions of human beings are warming the planet much faster than just natural processes. ‘The Mediterranean Sea is warming up. The sea is also receiving less rainfall and less terrestrial runoff, which is making the sea more saline [salty]. All of these phenomena are leading to many changes occurring at the same time. The first thing that you are getting is that native species, which were limited to the warmer parts of the Mediterranean, can extend their range to the colder parts, so southern species are moving northwards. It means that the cold-loving species cannot move further north, because we are completely surrounded by land. So populations of cold water species are becoming rarer and less distributed and if things go on like that some might become extinct because they cannot escape. In the Atlantic they just move further north, but not here, they cannot do that.’

“A warming sea is one main reason why new alien and sometimes invasive species are being found in Malta all of the time”

Loss of species is not the only thing a warming sea causes. ‘The second thing observed is that species from the East Mediterranean, which is the warmest and most saline part of the Mediterranean [and includes many species that invaded from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal], are moving westwards. Species which are warm water Atlantic species enter the Mediterranean and are now moving eastwards.’ This means that these species are all passing by Malta as they disperse, making the island an ideal monitoring station to observe a changing Mediterranean.

A warming sea is one main reason why new alien and sometimes invasive species are being found in Malta all of the time. These species are making great leaps. Dr Julian Evans, Dr Joseph Borg, and Schembri have recently (2013) found for the first time the Red Sea sea squirt Herdmania momus in Malta. This record is 1,300km further west than ever before. This sea squirt came through the Suez canal, established itself in the Levantine Sea off Lebanon, and was last observed around Greece and Turkey. It is not the only foreigner that has established itself in our waters.

Schembri and one of his collaborators Dr Marija Sciberras saw the nimble spray crab (Percnon gibbesi) all along Maltese shores. This crab is an Atlantic species that entered the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar in the late 1990s. When they found it in Malta they did not just collect it — they studied it. They found that this shallow water species grows ‘up to a depth of 3m, in other parts of the Mediterranean they have found it down to depths of 10m. It needs a habitat of cobbles or stones, it does not live on bare rock. [In Malta this means] that you find it more towards the north rather than the south, because the coast slopes down to the north and you’ve got many more opportunities for this sort of habitat while the south is mainly cliffs.’ The local shore crab (Pachygrapsus marmoratus) also beats this invader. They saw that the local crabs are much more aggressive than the invader. The nimble spray crab has mostly occupied a niche different from that of local shore crabs.

When we hear the word invader we do not imagine a mostly plant-eating crab sneaking into a new niche while the local omnivorous crab remains reigning supreme; but an invasive species ‘simply means that it spreads very quickly. [To understand] what the effect on the ecosystem is requires many years of study. We have many invaders. Another one, which is even more invasive, is a seaweed — an algae (Caulerpa racemosa) — this is now found everywhere. What does it do? What effect does it have on the local ecosystem? I don’t know, nobody does.’ This is why we need to invest more into scientific research over many years. You cannot figure out how a species is acting

overnight.

Schembri has been studying Malta’s ecology for decades. This long-term knowledge is vital to see slow trends like a warming Mediterranean, climate change, or habitat loss. When I asked him about the changes affecting Malta and Gozo, he replied in a sombre voice ‘I’ve seen a lot of change. In terms of change of habitat, apart from places which have been developed, not much has changed on the open coast. What has changed are the characteristics of the community. For example, previously you used to find large limpets, now you’ll find small limpets. That sort of thing. You haven’t lost a limpet or had a complete change in the ecosystem, but there have been changes nonetheless.’

In some places, especially sheltered areas, things have changed drastically. For his Master’s degree, Schembri collected specimen from Marsaxlokk Bay. This was many years before the development of the Freeport and Delimara power station. When he had a look at it after these developments the species he studied had vanished. ‘The bay has changed and when they started dredging it was even worse because a lot of the sea grasses disappeared. That bay was full of sea grasses before.’ Schembri does not think they will return anytime soon. Loss of sea grasses are even eroding the shore. ‘The sea grass was acting as a buffer to the waves, although it could also be because people have been building breakwaters and things which would change the current patterns which would also cause erosion. These things are complicated and without studying them it is difficult to know and nobody has looked’ — another reason for more researchers and funds being needed.

Marsaxlokk is not the only place. Especially since the 1990s the Maltese coast has been heavily built up, with developments sprouting in many picturesque areas like Armier. Dealing with this development has become a political issue, rather than seeing the consequences from a scientific lens.

Schembri’s view on this change is a bit peculiar to me. When I referred to the changes in Marsaxlokk Bay as ecological devastation he replied saying, ‘I don’t talk about ecological devastation, because what life does is that if the environment changes certain things disappear and other things take their place. Saying it is devastation is a human emotion. Scientifically it’s not what happens.’ Schembri was speaking impersonally from an ecological perspective. I find it hard to see the complete loss of a species or beautiful area because of human progress in this way. If humans are doing the destruction, humans can stop it or reduce the problem.

Ecologists for Tomorrow

Ecologists like Schembri are vital to know the changes taking place around our islands. Without monitoring our land and seas we cannot know how to preserve them so everyone can enjoy them. Nature should be for everyone to enjoy and experience.

Malta’s situation has definitely improved. ‘We have a huge marine protected area going all the way from Qala in Gozo to Portomaso in St Julians to protect all the seagrass meadows there. How are we managing it? We’re not. It’s a line on a map, but it is a first step’ since if anyone wants to develop the area the development’s impact on the ecology needs to be rigorously studied. Unfortunately, no one knows if the sea grasses are doing well or not. The problem is that the area is huge. ‘You don’t try to keep track of every single square metre of sea grass but at least you keep track of some of them. You establish a monitoring programme, the Government is obliged to do it having declared a marine protected area in terms of the Habitats Directive, and some monitoring is being done but there is no management plan.’ The problem is that Malta is an island with limited resources and 10 people abroad would perform one person’s job here. Government needs to give the environment and science more importance.

Schembri’s flexible approach to research is powerful. He makes it work despite the odds, but I do wonder how much more we would know about Malta’s natural wealth if there were many more researchers studying the Maltese environment and if they had better support. There are other researchers apart from Schembri, but they are few. For such a serious man, serious investment in research would surely make him, and future generations, smile.

Find out more:

-

Sciberras, M. & Schembri, P.J. (2008) Biology and interspecific interactions of the alien crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne-Edwards, 1853) in the Maltese Islands. Marine Biology Research 4: 321-332.

-

Costantini, F., Taviani, M., Remia, A., Pintus, E., Schembri, P.J. & Abbiati, M. (2010) Deep-water Corallium rubrum (L., 1758) from the Mediterranean Sea: preliminary genetic characterisation. Marine Ecology 31: 261-269.

-

Gravino, F., Dimech, M. & Schembri, P.J. (2010) Feeding habits of the small-spotted catshark Scyliorhinus canicula (l., 1758) in the Central Mediterranean. Rapport du Congrès de la Commission Internationale pour l’Exploration Scientifique de la Mer Méditerranée 39: 538.

-

Evans, J., Borg, J.A. & Schembri P.J. (2013) First record of Herdmania momus (Ascidiacea: Pyuridae) from the central Mediterranean Sea. Marine Biodiversity Records 6: e134; 4pp. [Online. DOI: 10.1017/S1755267213001127]

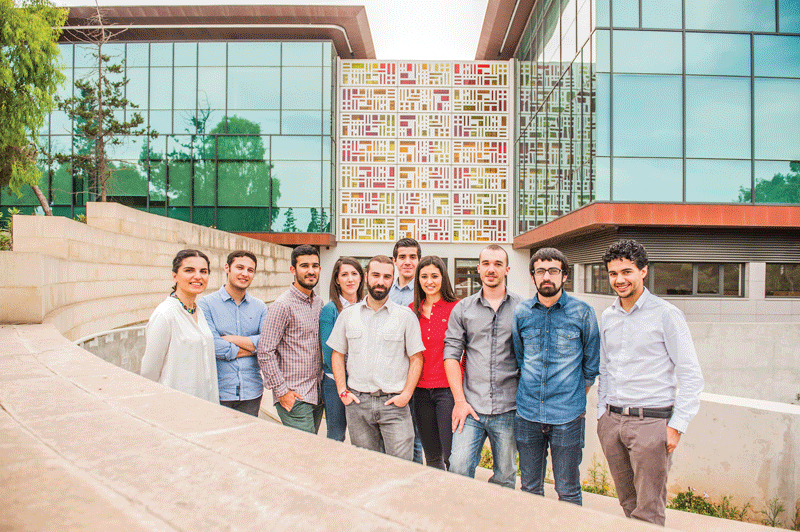

The 2007 team placed 17th out of 20 teams. The new team has stiff competition and huge challenges to overcome for the upcoming competition in July 2014. Foreign universities compete every year and build a database of knowledge and experience which students use to continue improving their cars. For the UoM to compete eff

The 2007 team placed 17th out of 20 teams. The new team has stiff competition and huge challenges to overcome for the upcoming competition in July 2014. Foreign universities compete every year and build a database of knowledge and experience which students use to continue improving their cars. For the UoM to compete eff