Conserving brushstrokes

A new conservation project will soon start work on one of Malta’s most significant historical artworks. Laura Bonnici meets Prof. JoAnn Cassar, Jennifer Porter, Dr Chiara Pasian, and Roberta De Angelis to find out why conserving the d’Aleccio Great Siege Wall Painting Cycle is of national importance.

Continue readingScience, dance, and Scotland

What if I told you that I could explain why the sky is blue through dance? All I would need is a fiddle player, a flautist, and a guitarist. By the end of it, we would all be dancing around like particles, hopefully with a better understanding of how the world around us works. This is exactly what neuroscientist and fiddle player Dr Lewis Hou does on a daily basis. Sitting through a boring science class with a teacher blabbing on about how important the information is might be a scene way too familiar for all of us. The science ceilidh (a traditional Scottish dance) aims to combat this misconception that science is all about memorising facts. Bringing people together to better understand and represent the processes within science through interpretative dance and other arts, the ceilidh has been proving a fruitful way of engaging people who would normally not be interested in science or research. ‘For us, that’s a really important guiding principle— reaching beyond those who usually engage,’ says Hou.

It all starts by bringing everyone together in one room. Researchers, musicians, and participants all get together. Researchers kick off the conversation by explaining what their work is and why it is relevant. Hou then helps the rest of the group break the scientific process down into its fundamental steps, be it photosynthesis, cell mitosis, or the lunar eclipse. The next step is translating each of the steps into a dance. And this is where everyone gets involved.

For us, that’s a really important guiding principle— reaching beyond those who usually engage.

Thinking back on how the idea came together, Hou says his first motivation to combine dance and science came when he was playing music and calling ceilidhs, all while attending as many science festivals as he could. ‘I realised there’s a big crossover with the spirit of folk music and dance—it’s all about participation and sharing. Everyone takes part even if they aren’t experts—and that is what we want to achieve in science communication. We want to encourage more people to feel able to participate without being scientists.’

‘Importantly, the nice thing about ceilidh dance is that they might be simple, but it also means that many people can join in and dance,’ emphasises Hou. Back in the studio, aft er having understood the science and its concepts, everyone works together to create the choreography. The science merges with their artistic interpretation. It is no longer something out of reach; it is now owned by everyone in the room.

Author: Abigail Galea

Grassroot legacy

Capitals of Culture want legacy. Wrocław 2016 established a microgrant system for small operators that is still in place. Aarhus 2017 combined qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate a city’s cultural sustainability. Valletta 2018 wants to leave behind a vibrant grassroots movement actively shaping the country’s cultural policy. Rachel Baldacchino speaks to Szilvia Nagy to find out how this is possible…

Continue readingLuzzu Truths

Strolling along Malta’s coast, you’ll be mesmerised by the rainbow of traditional fishing boats ambling on the water—that and all the eyes ogling at you from their bows. Katre Tatrik takes a closer look at the hidden meaning behind the luzzu’s colours.

The Maltese luzzu dates back to the time of the ancient Phoenicians. For generations, Maltese fishermen have painted them in a kaleidoscope of bright colours, turning them into a national icon. But is there rhyme or reason to the hues they choose? Lifelong fishermen, brothers Charles (62) and Carmelo (70) from Marsaxlokk, paint their luzzus twice a year in bold blues, reds, and yellows. It’s no easy task, requiring thorough cleaning and six layers of paint. Despite their dedication, Charles and Carmelo, like many others, are largely unaware of the hidden meanings the colours on their boats carry. ‘They’re all the same,’ Carmelo says. ‘It’s just for beauty.’ Charles adds that ‘these boats have always looked the way they look.’

But in 2016, Prof. Anthony Aquilina from the University of Malta embarked on a project that would uncover more. ‘Contrary to what you have been told, there is a lot of meaning in the way our traditional boats are painted,’ he explains. Aquilina edited and published The Boats of Malta – The Art of the Fisherman, written by world-famous anthropologist Desmond Morris.

Morris resided in Malta for six years in the 1970s, visiting each of the fishing villages on the islands. During his stay, he sketched some 400 of the 700 traditional boats anchored in the coastal villages. He wrote: ‘to visit a Maltese fishing village is like entering a huge, open-air art exhibition.’

Summing up Morris’ work, Aquilina says that ‘even in a small country, you can see the difference between one locality and another. But at the same time, there is the individual stamp of the fisherman, of that particular person.’

To visit a Maltese fishing village is like entering a huge, open-air art exhibition.

Morris’ main findings show that some traditional rules come into play when choosing the colour palette for a luzzu.

Whilst reddish brown or maroon was typically painted on the lower half of the boat to mark the waterline, the locality of a boat’s owner could be identified by the colour of its mustaċċ. The mustaċċ is the band above the lower half of the boat, shaped like a moustache, which gives the feature its name. A red mustaċċ would indicate that the boat came from St Paul’s Bay, for example. A lemon yellow indicated a boat from

Msida or St Julian’s, whilst an ochre yellow one would identify the boat as hailing from the Marsaxlokk and Marsascala area. When a mustaċċ was painted black, it denoted mourning for a death in the family.

In addition to colours, decorations also send a message. In more than half of luzzus, signature eyes are painted on the bow or the stern—symbols of protection for fishermen out at sea. Where the eyes are not seen, other symbols such as a rising sun, a Maltese cross, fish, shooting stars, or lions are painted on. The gangway, usually varnished brown, can be heavily decorated or engraved with symbols of the sea and the island: shells, mermaids, birds, flowers. Religious insignia are common too, with doves, olivebranches, and lambs often making an appearance.

Political or religious influences also come into play where a luzzu’s name is concerned. During the time we spent in Marsaxlokk, we saw San Mikiel (Saint Michael the Archangel, patron saint of Isla), John F. Kennedy, and Ben Hur.

Even if Charles and Carmelo couldn’t tell us what the luzzu’s colours mean, their dedication to tradition is undeniable. Before we left, they said they were fearful that this part of Malta’s heritage may fade away as featureless carbon-fibre boats wade in. I hope they’re wrong.

Author: Katre Tatrik

Il-letteratura u s-snin tmenin

Hemm min jgħid li konna viċin gwerra ċivili, hemm min ma jaqbilx. Li hu żgur hu li fil-letteratura, is-snin tmenin ħallew impatt b’diversi modi; mhux biss fin-narrattiva li nkitbet dakinhar, imma wkoll l-epoka bħala sfond ta’ plott jew ispirazzjoni għall-awturi kollha li sabu refuġju fiha biex jesprimu l-arti tagħhom. Kliem ta’ Emanuel Psaila.

L-aspett soċjali għandu importanza kbira u l-medda taż-żmien hija vitali biex nifhmu dak li ġara fit-tmeninijiet, nifhmu għaliex seħħ, x’ġiegħel lill-poplu Malti jirreaġixxi b’dak il-mod, u x’sehem kellha l-letteratura f’dan kollu. Fuq kollox: kien ir-riżultat pervers tal-elezzjoni ġenerali tal-1982 li qanqal dan kollu? Jew l-għeruq kienu ilhom ġejjin mis-sittinijiet u saħansitra mit-tletinijiet?

Kienet ħaġa naturali li fit-teżi tiegħi Is-snin tmenin u l-prożaturi Maltin (iggwidat minn Dr Adrian Grima) inwaħħad flimkien żewġ affarijiet li nħobb: il-politika u l-letteratura. Apparti minn dan, fis-snin tmenin kont żagħżugħ militanti fi ħdan grupp politiku. Biss it-teżi għenitni nifhem perspettivi oħra, nara affarijiet li sa ftit snin qabel ma kontx nifhimhom, kif ukoll li nfittex it-tekniki u l-għodod tal-letteratura li titkellem fuq dan iż-żmien.

Il-letteratura li dejjem ippruvat tqanqal ħsibijiet ta’ kuxjenza ċivili u soċjali kienet tappartjeni lill-esponenti xellugin u fit-tletinijiet bdejna naraw kitbiet minn dawk li ftit snin qabel kienu xxierku fil-Partit Laburista Malti (hemm bosta biex issemmihom kollha). Dawn kienu jafu x’ġara u x’qed jiġri f’pajjiżi oħra, bħal Franza, l-Ingilterra, il-Ġermanja, u l-Istati Uniti, u għalhekk użaw il-letteratura biex imexxu ’l quddiem l-ideoloġija tagħhom. Użaw stili u ġeneri differenti, imma l-għan ewlieni kien li jnisslu kuxjenza soċjali, biex jgħinu lill-batut, jedukaw, u jgħallmu.

Lejn l-aħħar tas-sebgħinijiet u l-bidu tat-tmeninijiet din l-istrateġija fil-letteratura ntużat minn kamp ieħor differenti u rajna esponenti tal-lemin jiktbu letteratura diretta b’għan li tikxef il-qagħda politika reali tal-epoka. Trevor Żahra kien minn ta’ quddiem nett. Il-kotba tiegħu Trid Kukkarda Ħamra f’Ġieħ il-Biża’ u It-Tmien Kontinent huma novelli li jattakkaw b’ironija diretta u b’sarkażmu qawwi lill-gvern tal-ġurnata. Żahra wkoll daħħal element qawwi ta’ politika fi ktieb għat-tfal Qrempuċu f’Belt il-Ġobon fejn mhux faċli ssib il-parodija midfuna taħt parodija oħra. Biss meta l-qarrejja jindunaw biha, l-ironija tant tkun qawwija li ssir drammatika.

Ktieb li kien fuq fomm kulħadd fit-tmeninijiet huwa r-rumanz Fil-Parlament ma Jikbrux Fjuri (1986) ta’ Oliver Friggieri. Huwa rumanz filosofiku ħafna u ftit kien hemm min fehmu, biss nofs Malta xtrat ir-rumanz u n-nofs l-ieħor warrbitu. Dan ir-rumanz intuża bħala propaganda mill-Partit Nazzjonalista għall-elezzjoni tal-1987. It-tnedija tiegħu f’lukanda prominenti kienet qisha manifestazzjoni u saħansitra nqaleb bħala dramm u ntwera għal ġimgħa wara ġimgħa. Madanakollu l-istrateġija rnexxiet u l-letteratura kienet strumentali biex issir bidla.

Apparti l-letteratura tas-snin tmenin, dan iż-żmien sar sfida biex tinkiteb narrattiva dwaru. Wieħed minn tal-bidu li uża dan l-isfond kien Immanuel Mifsud. L-Istejjer Strambi ta’ Sara Sue Sammut huwa kollu mpoġġi f’dan il-kuntest. L-ironija, is-sarkażmu, u ċ-ċiniżmu jinħassu sew u għalkemm inisslu tbissima fuq fomm il-qarrejja, iħallu stampa reali.

Clare Azzopardi ilha tesperimenta fuq is-snin tmenin u ktieb wara ktieb qed iżżid id-doża tagħha. Id-dramm tagħha L-Interdett Taħt is-Sodda jitkellem dwar il-kwistjoni politika reliġjuża tas-snin sittin u minn hemm naraw kemm Azzopardi qed tnawwar fil-fond fuq żminijiet li kienu nieqsa mil-letteratura tal-epoka. Fin-novella Linja Ħadra, li hija parti minn ġabra li ġġib l-istess isem, hemm l-ewwel mistoqsijiet u l-isfond huwa l-istrajk tal-għalliema f’nofs is-snin tmenin. Id-doża politika, għalkemm sottili, żdiedet f’ġabra oħra ta’ novelli – Kulħadd Ħalla Isem Warajh – fejn isem Dom Mintoff, personaġġ li jiddomina t-tmeninijiet, jinsab minqux f’kull novella taħt l-akronomu PDM. Jidher li Azzopardi qed tipprova tgħix il-memorja tas-snin tmenin permezz tal-letteratura. L-aħħar rumanz tagħha, Castillo, jitkellem b’mod ċar fuq it-tmeninijiet, dwar il-bombi li kienu jsiru, dwar ir-rwol tal-pulizija u dwar r-relazzjonijiet li kellu l-Gvern Malti ta’ dak iż-żmien, speċjalment ma’ Gaddafi.

Pierre J. Mejlak isemmi t-tmeninijiet mil-lenti ta’ tifel żgħir li trabba fil-Każin Nazzjonalista tal-Qala, Għawdex. F’Qed Nistenniek Nieżla Max-Xita hemm xi novelli b’laqta awtobijografika li fihom nistgħu nħossu t-tensjoni tal-elezzjoni ġenerali tal-1987 kif ukoll iċ-ċelebrazzjonijiet mar-rebħa tal-Partit Nazzjonalista.

Ġużè Stagno fix-xogħlijiet tiegħu jdaħħal battuti ta’ persuna li għexet Marsaxlokk u jitfa’ botti bħall- kwistjoni tat-televixin tal-kulur li kien novità għal dak iż-żmien.

Is-Sriep Reġgħu Saru Velenużi ta’ Alex Vella Gera għandu l-plott ibbażat proprjament fuq kumplott ta’ qtil tal-Prim Ministru Dom Mintoff u miktub b’mod miftuħ, tant li n-narratur u l-protagonist huwa Nazzjonalist kbir.

Hemm ukoll kittieba oħra li jużaw dawn is-snin bħala sfond biex jibnu l-plott u rumanz li l-ftuħ tiegħu huwa bbażat fuq din l-epoka huwa Xandru Miżżewweġ u Gay ta’ Javier Vella Sammut.

Kull deċenju fih tiegħu, u kollha xi ftit jew wisq għenu fl-iżvilupp tal-letteratura. Inħoss li fit-tletinijiiet ippruvajna nersqu lejn dak li kien qed jiġri barra minn Malta, imma l-gwerra tellfet l-iżvilupp ta’ kollox u kellna nistennew sal-ħamsinijiet biex bdejna naraw xi ħaġa żgħira. Fis-sittinijiet il-Moviment Qawmien Letterarju, għalkemm kien progressiv u kien hemm bżonnu, żamm lura milli jitkellem dwar l-attwalità speċjalment dwar il-kwistjoni politika reliġjuża. Biss is-snin sebgħin u tmenin reġgħu xprunaw lill-kittieba biex jiktbu fuq il-fattwalità u ma jibqgħux iktar passivi.

Is-snin tmenin, bit-tajjeb u l-ħażin tagħhom, u bit-turbulenza tagħhom, għenu ħafna fl-iżvilupp tal-letteratura Maltija u għalkemm għaddew tliet deċenji, kienu u ser jibqgħu jiġu mfittxija minn kittieba biex fuqhom isawru x-xogħlijiet tagħhom.

Transcendence through Play

Even though philosophers like Kant and Schiller of the aesthetic tradition never had the opportunity to troll some noobs in Call of Duty or slay a dragon in Skyrim, their views on the concept of play can be critical to our understanding of how the player relates to the game world. Dr Daniel Vella explores the work of aesthetic and existential philosophers. Words by Jasper Schellekens. Continue reading

The Philosophy of Creativity

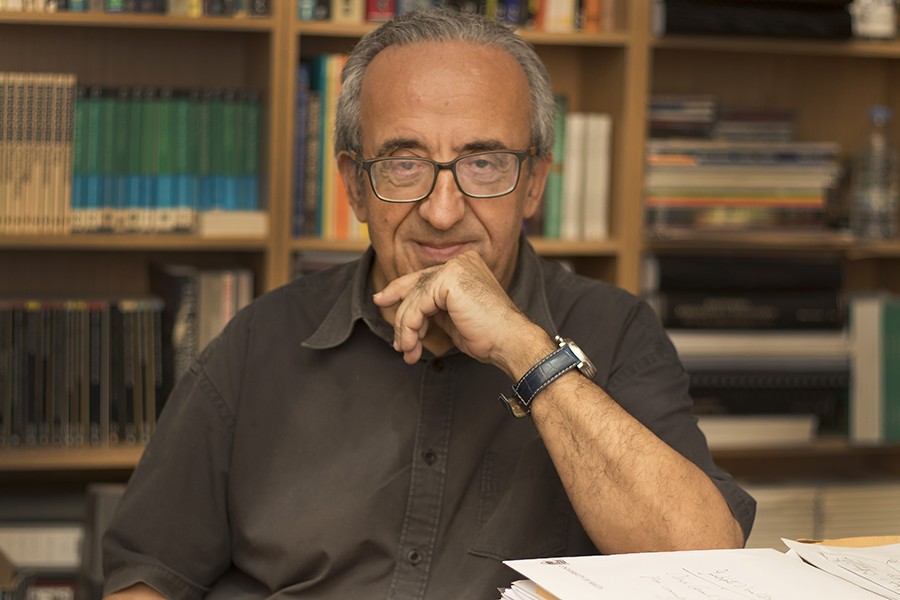

In this age of specialisation, finding a niche is key to most people’s career progression. But it is not the only way. Cassi Camilleri sits down with philosopher poet Prof. Joe Friggieri to gain insight into his creative process.

It was a very warm April day when I found myself sitting in front of Prof. Joe Friggieri. My heart was racing—I had just run up three flights of stairs for a rescheduled meeting after having missed our first earlier in the day. I had lost track of time while distributing magazines around campus. My eyes briefly scanned his library, wishing it was mine, then got right down to the business of asking questions.

Friggieri balances between two worlds: the academic and the creative. His series Nisġa tal-Ħsieb, the first history of philosophy in Maltese, is compulsory reading for philosophy students around the island. His collections of poetry and short stories have seen him win the National Literary Prize three times. I ask Friggieri if he separates his worlds in some way. ‘I can’t stop being a philosopher when I’m writing a short story or play. Readers and critics of my work have pointed that out in their reactions,’ he says. ‘I do not necessarily set out to make a philosophical point in my output as a poet, short-story writer, or playwright, but that kind of work can still raise philosophical issues.’

‘Dealing with matters of great human interest—such as love or the lack of it, happiness, joy and sorrow, the fragility of human relations, otherness, and so on—in a language that is markedly different from the one used in the philosophical analysis of such topics can still contribute to that analysis by creating or imagining situations that are close to the experiences of real human beings,’ Friggieri illustrates.

The urge to write

In reality, Friggieri is usually inspired by day-to-day moments, things normally overlooked in today’s loud and busy world. ‘In my literary works, I am inspired by what I see, hear, and feel; by people and events, by what I read about and by what I can remember,’ he says. It could be anything from a news item to a painting, a whiff of cigarette smoke, a piece of music, or a word overheard at a party. ‘All of that can trigger off an idea. Then, when I’m alone, I seek to elaborate the thought and to convey it to others by means of an image or series of images in a poem, or as part of the plot in a short story or play.’

While on the subject of inspiration and starting points, I wondered: how does Friggieri work? First, he swiftly explains his aversion to using computers for his writing. ‘I do all my writing the old-fashioned way,’ he notes. ‘I use pen and paper. I find it much easier to write that way than on my computer. It feels like my thoughts are taking shape literally as I push my pen from left to right across the page. I think with my pen, much in the same way that a concert pianist thinks with her fingers and a painter with her brush. It’s that kind of feeling that makes me want to go on writing.’ At this point, the subject of the Muse comes up. Is this something Friggieri believes in? ‘Waiting for the Muse to inspire you is just a poetic way of saying you need to have something to write about and you’re looking to find the right way of expressing it,’ Friggieri explains. ‘I write when I feel the urge or the need to write,’ he tells me with a smile.

The sheer volume of work Friggieri has built up over the years seems to imply that he writes daily. But in reality, his workflow is more akin to sprints than a marathon. He tells me deadlines are a good motivator for him to write, providing a tangible goal he can work towards. ‘My first two collections of short stories were commissioned as weekly contributions to local newspapers,’ Friggieri says. ‘That’s how ‘Ir-Ronnie’ was born.’ Ir-Ronnie is a man who finds himself overwhelmed by life’s pressures: family, work and everything in between. As he starts to lose touch with reality, ‘ordinary, everyday living becomes an ordeal for him, an obstacle race, a struggle for survival,’ says Friggieri. More recent works, such as his latest collections of short stories—Nismagħhom jgħidu and Il-Gżira l-Bajda u Stejjer oħra—also reflect this realism, exploring the complexity of interpersonal relations between different people from different walks of life. On the other hand, Ħrejjef għal Żmienna (Tales for Our Times) finds its roots in magical realism, which makes these stories a very different experience for his readers. The books have been well received, with translations into English, French, and German. Paul Xuereb, who worked on the English translation, described the tales as ‘drawing on the dream-world and waking reveries to suggest the ambiguity and often vaguely perceived reality of our lives.’

The Creative Philosopher

When it comes to talking about his other works and creativity, Friggieri often refers to language. When I asked him about his thoughts on creativity and whether he believed everyone to be ‘creative’, his response was positive. ‘As human beings, we are all, up to a point and in some way, creative,’ he says. A prime example is humanity’s use of language. ‘Think of the way we use language. Dictionaries normally tell you how many words they contain, but there’s no way you can count the number of sentences you can produce with those words. Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules. In a very real sense, every individual uses language creatively, in a way that is very much his or her own. I think the best way to understand what creativity is all about is to start from this very simple fact.’

Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules.

Is Friggieri creative when he writes his philosophical papers? ‘Yes,’ he nods. ‘Each kind of writing has its own characteristic features. But creativity is involved in all of them.’ With philosophy, ‘you need more time,’ he notes. ‘You need to know what others have said about the subject, so it involves researching the topic before you get down to saying what you think about it. When it comes to writing a poem or play, you’re much freer to say what you like, much less constrained.’

In fact, Friggieri has five plays under his belt. Here is where the two worlds of academia and creative writing merge. ‘In three of my five full-length plays, I make use of historical characters (Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Socrates) to highlight a number of issues in ethics and aesthetics that are still very much alive today,’ says Friggieri. Taking L-Għanja taċ-Ċinju (Swansong) as an example, Friggieri explains how ‘Socrates defends himself against his accusers by raising the same kind of moral issues one finds in Plato’s Apology. The Michelangelo and Caravaggio plays, on the other hand, highlight important questions in aesthetics, such as the value of art, the relation between art and society, the presence of the artist in the work, the difference between good and bad art, and the mark of genius.’

Talking of theatre, Friggieri remembers how, before writing his first play, he had directed several performances. This was where he learnt the trade and what it meant to have a good production. ‘I have also had the good fortune of working with a group of dedicated actors from whom I learnt a lot. In my view, one should spend some time working in theatre before starting to write for it.’

As time was pressing, and the sun was starting to move away from its opportune place in the window, I asked Friggieri one last question, the one I had been obviously itching to ask. What advice does he have for writers? The answer I got was one I should have expected. ‘Budding writers should write. Then they should show their work to established practitioners in the field. The first attempts are always awkward. As time goes by, one learns to be less explicit and more controlled, to use images to express one’s thoughts where poetry is concerned, to develop an ear for dialogue if one is writing a play, to produce well-rounded characters in a novel, construct interesting plots, and so on. All this takes time, but it will be worth the effort in the end.’ And with that, we had the perfect closing.

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Openness: The case of the Valletta Design Cluster

Valletta should be a unique experience, open to all. This is Valletta 2018’s key vision for the bustling capital. A group of people focused on making this a reality is the Valletta Design Cluster team. Located at the Old Abattoir site in Valletta, the initiative is going to create a community space for cultural and creative practice. Words by Caldon Mercieca.

According to Anna Wicher from the PDR International Centre for Design and Research, design is ‘an approach to problem-solving that can be applied across the private and public sectors to drive innovation in products, services, society and even policy-making by putting people first.’ This people-centred approach to design is not just a theoretical framework, but a concrete method that engages people in a co-creative process.

By bringing together people active in the cultural and social spheres, we want to have a concrete and meaningful impact on Malta’s diverse communities. We aim to provide support for students, start-ups, and creative enterprises and give social groups the necessary tools to empower those with different interests who nonetheless share the common purpose of using creativity for the social good. We also want to provide a new networking space for everyone. From students, to cultural and creative professionals, to residents, budding businesses and civil society groups, everyone will be welcomed at the Valletta Design Cluster.

This philosophy of openness and diversity is one that has permeated every aspect of the project from the very beginning. Over the past three years, we have consulted with residents, students, schools, higher education institutions, artists, makers, and creatives to build the vision for the space. A range of public and independent organisations are also contributing to the project, providing both expertise and generous support.

Thanks to the support from the European Regional Development Fund, the physical space for the Cluster as well as the urban public spaces around it are currently undergoing serious regeneration. Once finished, the Cluster will have a range of facilities, which were decided on following consultation with potential users. It will include a makerspace, coworking spaces, studios, a food-space, several meeting rooms and conference facilities, an exhibition space, and a public roof garden. All of these facilities have benefitted from input contributed by various potential users, by residents, and by organisations that have been interacting regularly with the team working on the Valletta Design Cluster.

We believe that a community can only truly reach its potential when it opens itself up to collaborations which share a common goal. This does not mean turning a blind eye to the challenges faced by the community on a daily basis, or to the ever-evolving scenario that surrounds it, but rather cultivating a readiness to learn, an aptitude to develop networks built on trust, and a capacity to address problems with a practical, positive, can-do attitude.

One valuable experience we are developing with our community stakeholders is Design4DCity. This annual initiative, which the Valletta Design Cluster team started back in 2016, sees creatives, residents, and local authorities joining forces to rework and improve a public space. We worked with the Valletta community in 2016, and continued with the Birżebbuġa community in 2017. In 2018 we plan to work again in Birżebbuġa as well as in Siġġiewi, and will involve children and young people in our public space projects. Such initiatives are providing very important insights into the application of collaborative, co-creative approaches involving multiple stakeholders.

But the work of the Valletta Design Cluster is not restricted to the restoration or transformation of space. For the past three years, we have collaborated with the Malta Robotics Olympiad, teaming up with artistic curators and student organisations from the University of Malta (UM) to design and construct the pavilion for Valletta 2018. By the end of the project, participants had constructed a fully-recyclable 300 square meter pavilion and presented it to the public. This year we also supported SACES, the architecture students’ association at the UM, through a number of design and construction workshops. Branching out, we have done work with a number of creatives from various backgrounds in projects involving video-capture, artifact-curation, narrative development linked to cultural identities, and flexible use of available space through appropriately constructed spatial modules.

Several workshops have also been held where project stakeholders were fully involved in training sessions, with the aim of building skills in user-centred design, applied to specific contexts. This meant interacting with students, researchers, creatives, residents, and organisations in developing what the Cluster can offer. One tool used in this process is the construction of a user persona, where the characteristics, interests and concerns of the user are gathered through interaction with potential users of a service. Students from a number of faculties have also provided their input in this process through dedicated workshops at the UM.

They also stressed that the Cluster needed to serve as a catalyst for networking and for strengthening entrepreneurial skills for people working in the creative sector.

All of this has become possible thanks to continuous collaboration and international networks which have contributed their resources to our projects. To assist us in this, the Valletta 2018 Foundation has joined Design4Innovation, an Interreg Europe project bringing together eight European countries all working towards using design to benefit society.

While we have been on the receiving end of a lot of support, translating our philosophy of openness into practice involved an element of risk. During a series of tours that we organised on site for potential users of the Cluster, we had to be open to various views and perspectives about what the Cluster could be. Participants highlighted issues related to accessibility and affordability as key concerns. They also stressed that the Cluster needed to serve as a catalyst for networking and for strengthening entrepreneurial skills for people working in the creative sector. In some cases, we had to revisit some of our plans and open new discussions with the architects to made adjustments. On other occasions, we called people in again to discuss their ideas further and see how we could integrate their suggestions into our vision.

Although we speak of cultural and creative industries, we should realise that the average number of people working in any single company is two. Indeed, 40% of designers in Malta are actually freelancers. The challenge for the Valletta Design Cluster here is to ensure flexibility and adaptability both in the physical infrastructure as well as the management of the Cluster. In this way, we can make the facility relevant for our users’ current needs, as well as cater to future ones.

The next stage in understanding our community of potential users better is to work together on the creation of a Design Action Plan. The Design Action Plan will highlight concrete actions to be undertaken by the Cluster during the first three years of its operation. It will serve as the main reference tool to structure the Valletta Design Cluster’s interaction with its community of users, practitioners, enterprises, and beneficiaries. Based on this open process, the Valletta Design Cluster aims at establishing itself as a new community-driven platform for cultural and creative practice in Malta.

Author: Caldon Mercieca

Instant Photography

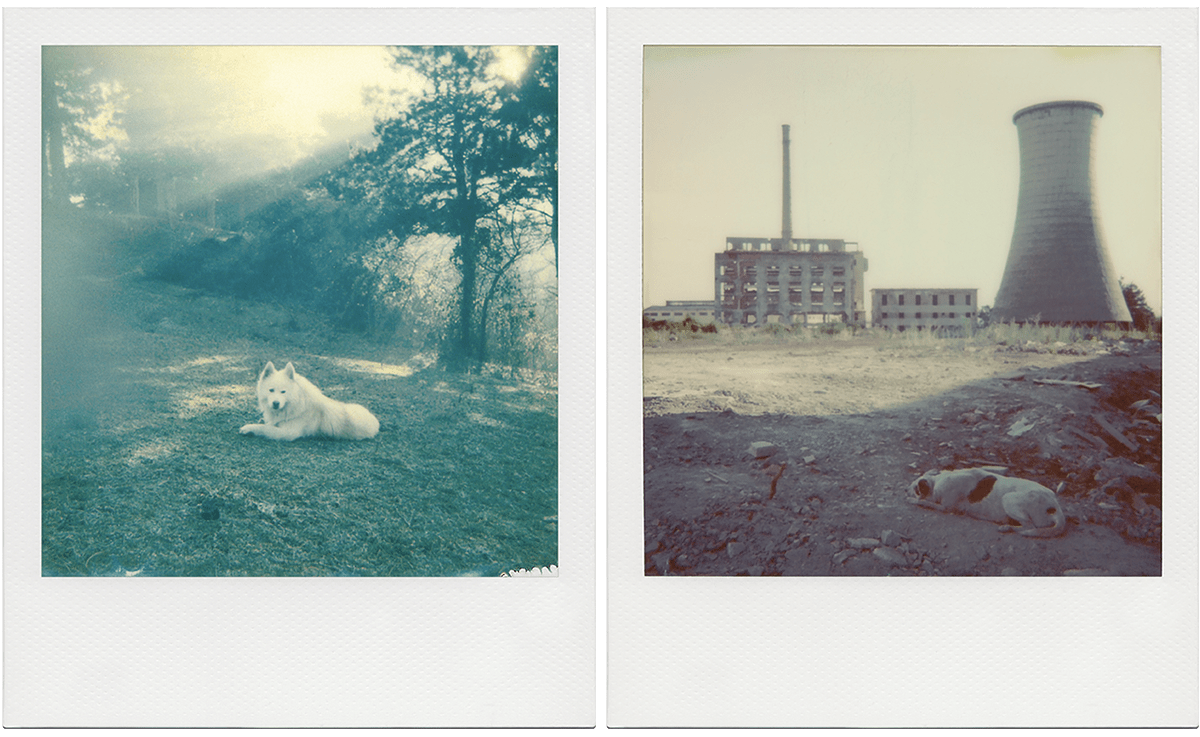

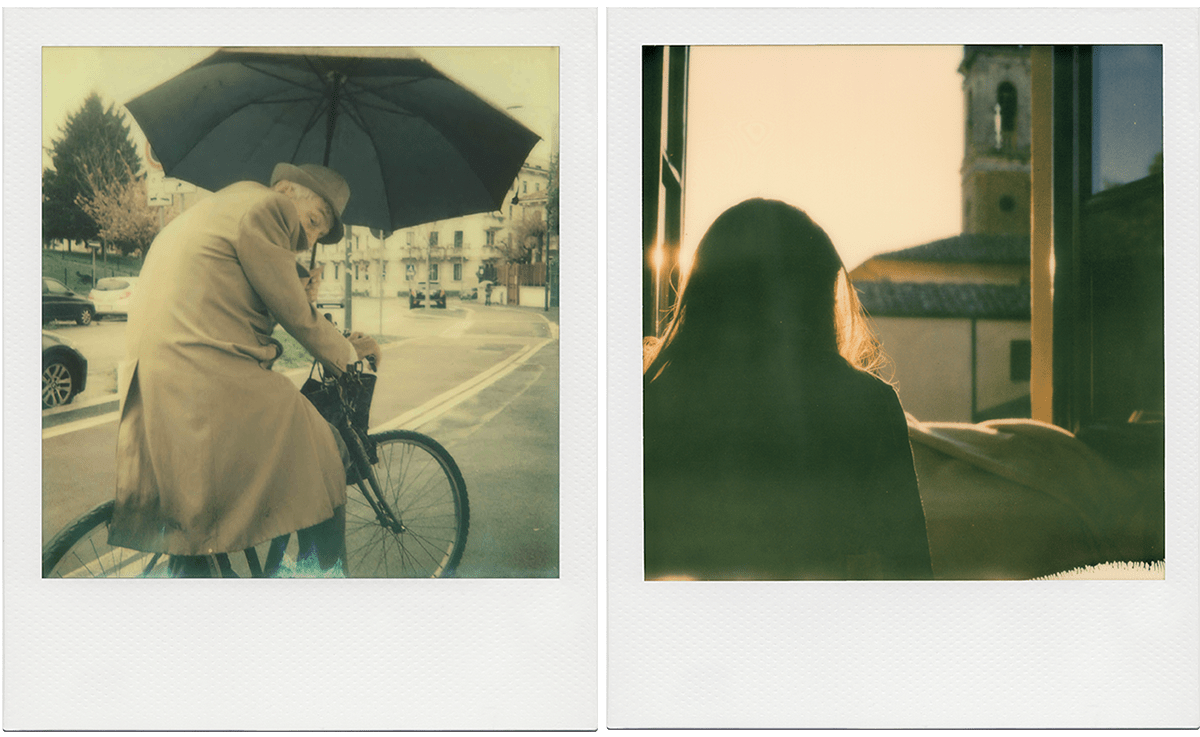

Instant cameras, commonly referred to as ‘Polaroids’ thanks to the pioneering company, offer limited manual-automatic controls. These self-developing photographs present numerous analog imperfections, but additional aspects make them distinctive.

Polaroids do not document the world faithfully. They create a new version of it through their own lighting schemes, colours, and softness; a quality associated with past technologies. All these aspects enhance the transient nature of subjects, such as boy counting in during a game of hide-and-seek (see picture).

The process of capturing an image can also draw from ‘missed opportunities’. These are subjects one comes across but does not photograph due to not having a camera at hand, or for fear of intrusion. A line of people coming down a hill, or visitors waiting like purgatorial souls outside a derelict hospital—such images are captured in the mind and their essence might be transferred into other shots.

Having the image in hand within minutes does not necessarily make the medium of instant photography unique, for even the photos themselves can change hues and mood with time. What does make it unique is its unpredictability and the challenge it poses when it comes to materialising intentions within the limitations of the medium. This makes the effort worth pursuing.

An image illustrates the relationship between a subject and its viewer. It is a perspective on the world, be it a printed photograph, a digital file, or a memory.