Cesar A. Cruz famously said that ‘art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.’ People have placed plenty of emphasis on the second half of that sentence—art is often used to provoke and make the viewer rethink their perception of the world. But what about the first half of that famous maxim? Can art serve as a comfort to those enduring difficult times? Pamela Baldacchino, the artist who founded the Deep Shelter project, certainly believes so.

Cesar A. Cruz famously said that ‘art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.’ People have placed plenty of emphasis on the second half of that sentence—art is often used to provoke and make the viewer rethink their perception of the world. But what about the first half of that famous maxim? Can art serve as a comfort to those enduring difficult times? Pamela Baldacchino, the artist who founded the Deep Shelter project, certainly believes so.

Baldacchino has experience with serious illness. Not only is she a qualified nurse, but she also suffered from fibromyalgia for 14 years, a chronic condition characterised by constant pain, fatigue, and trouble sleeping.

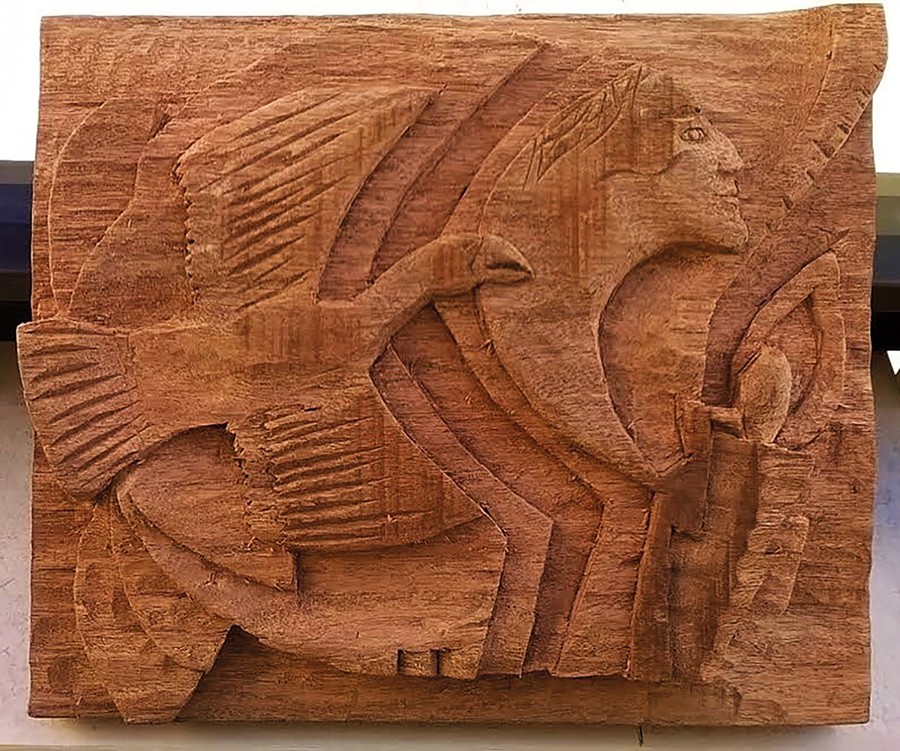

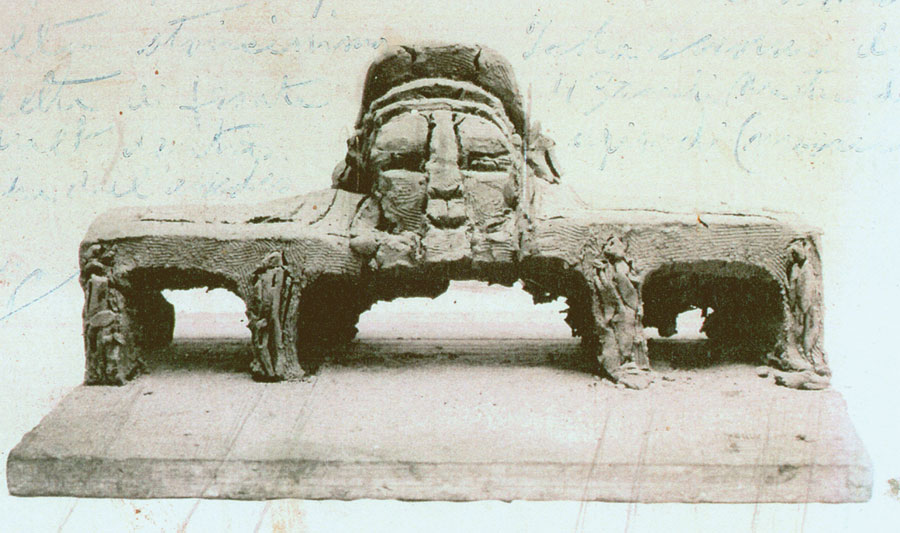

While reading for her Master’s degree in Fine Arts, Baldacchino created an audiovisual work purposely designed for a hospital environment. The work expressed empathy with patients by erasing the distinction between the sufferer and the audience, visually and symbolically showing states that merge into one another; the flesh of the artist’s hand becomes one with the ‘flesh of the sea’, for example. In another piece, the boundaries between sky, earth, and tree blur. She wanted to explore the concept further, to take her ideas beyond her degree and see them implemented in a practical manner within a clinical environment. With this goal in mind, she successfully acquired funding from the TAKEOFF Business Incubation Centre (University of Malta) as well as Arts Council Malta. Deep Shelter also forms part of the Valletta 2018 Cultural Programme and was presented during the Living Cities, Liveable Spaces conference held in November.

Others embraced Baldacchino’s approach to use art in helping those suffering from illness. A mutual friend introduced her to Dr Benna Chase, a psychologist within the Oncology Department (Mater Dei Hospital), who started using Baldacchino’s work during therapy with her patients. They then met clinical aromatherapist Marika Fleri, and the trio was complete. ‘We realised how much in sync we were. Through completely different mediums, we came together with instant understanding,’ Chase says.

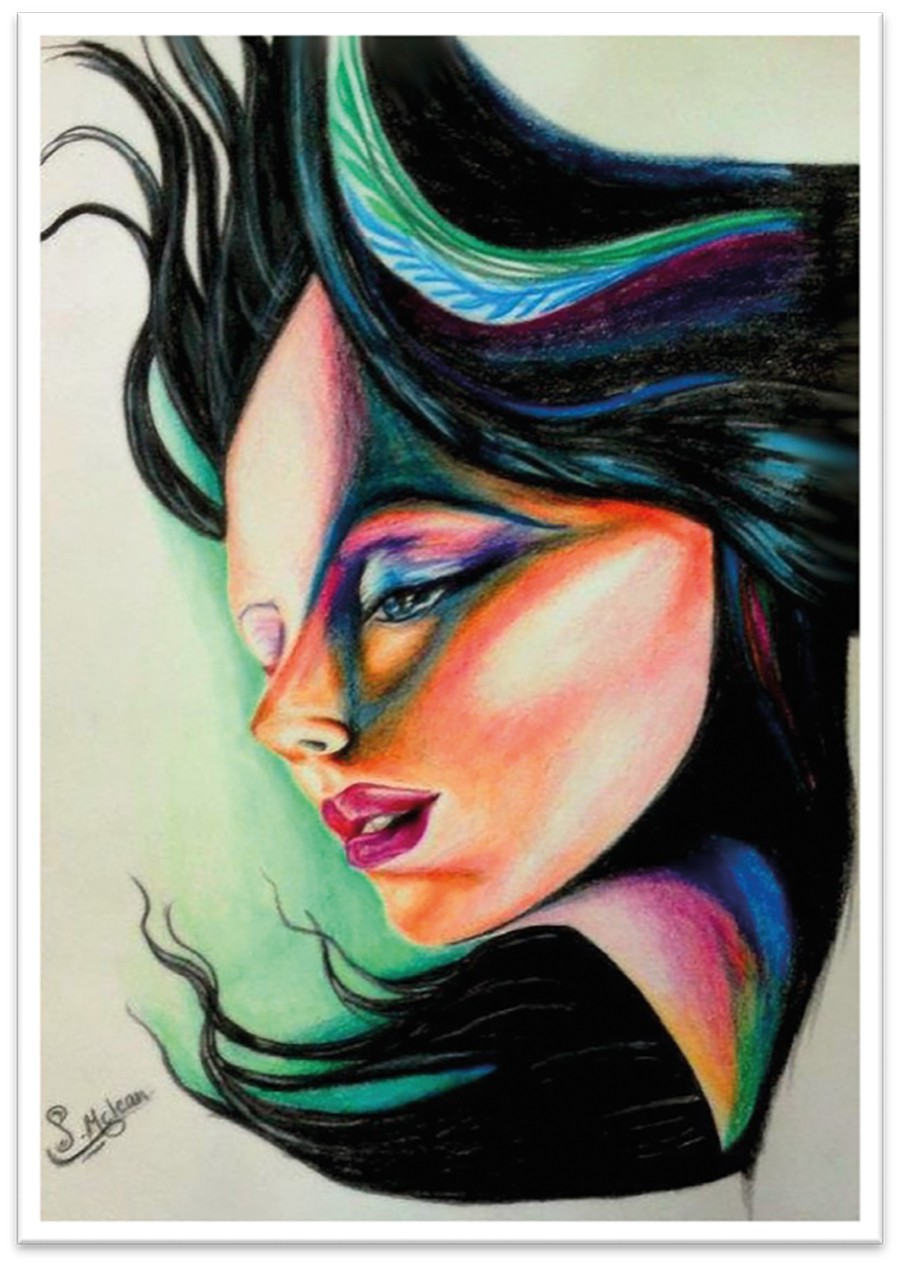

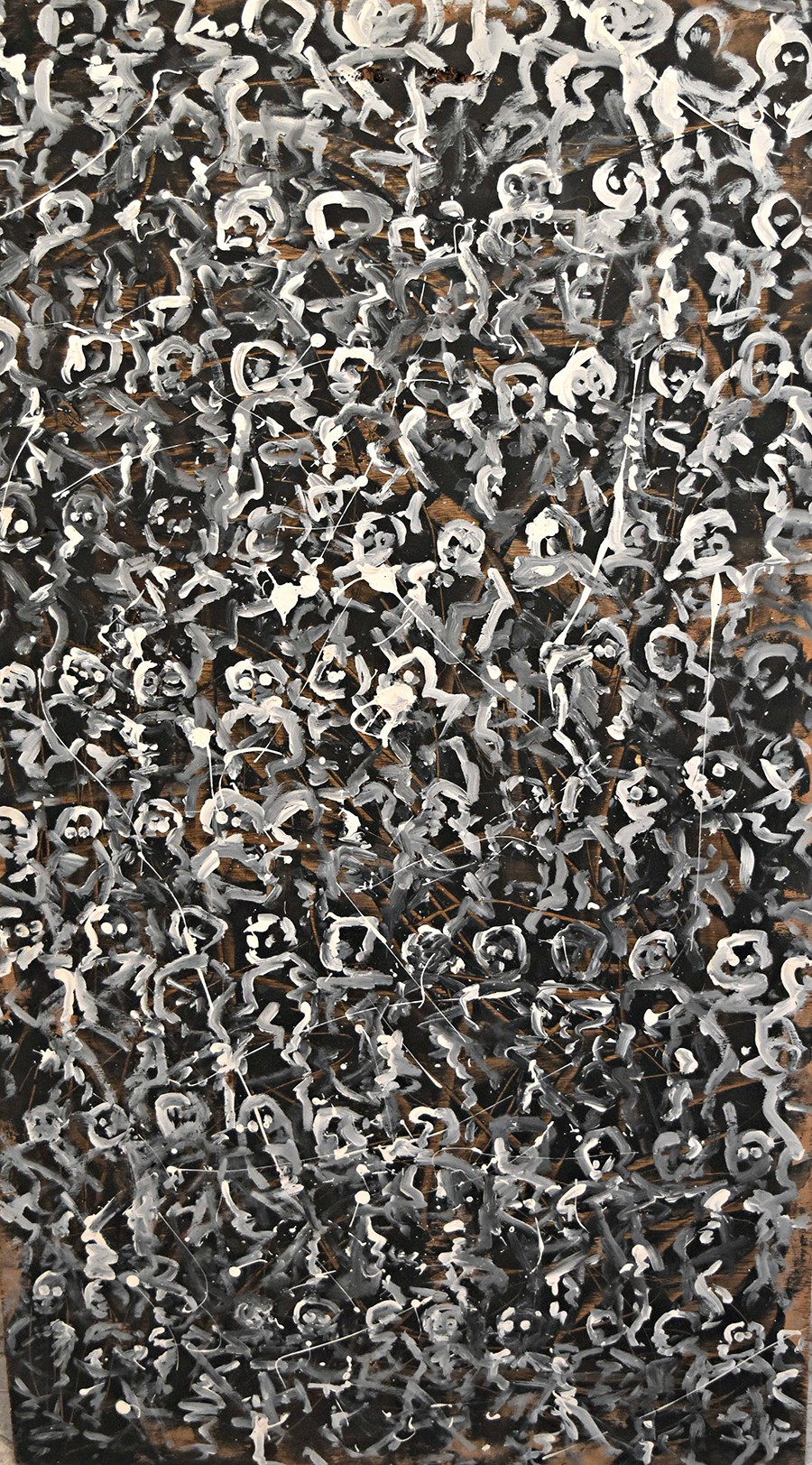

As the Deep Shelter project, they have organised two series of sensory workshops, consisting of six sessions each, as well as artist workshops for the creation and donation of artworks to clinical hospital spaces. Some of these workshops were aimed at people in palliative care, many of whom are aware that they are nearing the end of their lives. The workshops aimed to help them recognise, create, and make use of the ‘language’ that art provides when words are not enough.

“It is difficult for patients whose lives are punctuated by clinical sights, sounds, and smells to feel in tune with nature.”

‘In one of the workshops, author Leanne Ellul started reading from Tereża, a book she translated about a girl during the Second World War. Several of the patients had lived that experience and it took them back to their own childhoods. Then, we asked composer and percussionist musician Luke Baldacchino to pick up on the feelings conveyed in the writing, compose a piece of music, and play. We realised that something was happening within them,’ Baldacchino says. The most marvelous transformation was in an elderly woman who usually sat perfectly still and was almost totally unresponsive to the outside world. ‘While we were using spoken language, we couldn’t manage to get through, but then a piece of music brought a rare smile to her face. Through this alternate sensory experience, we were allowing processing to happen; it’s a form of therapy as well.’

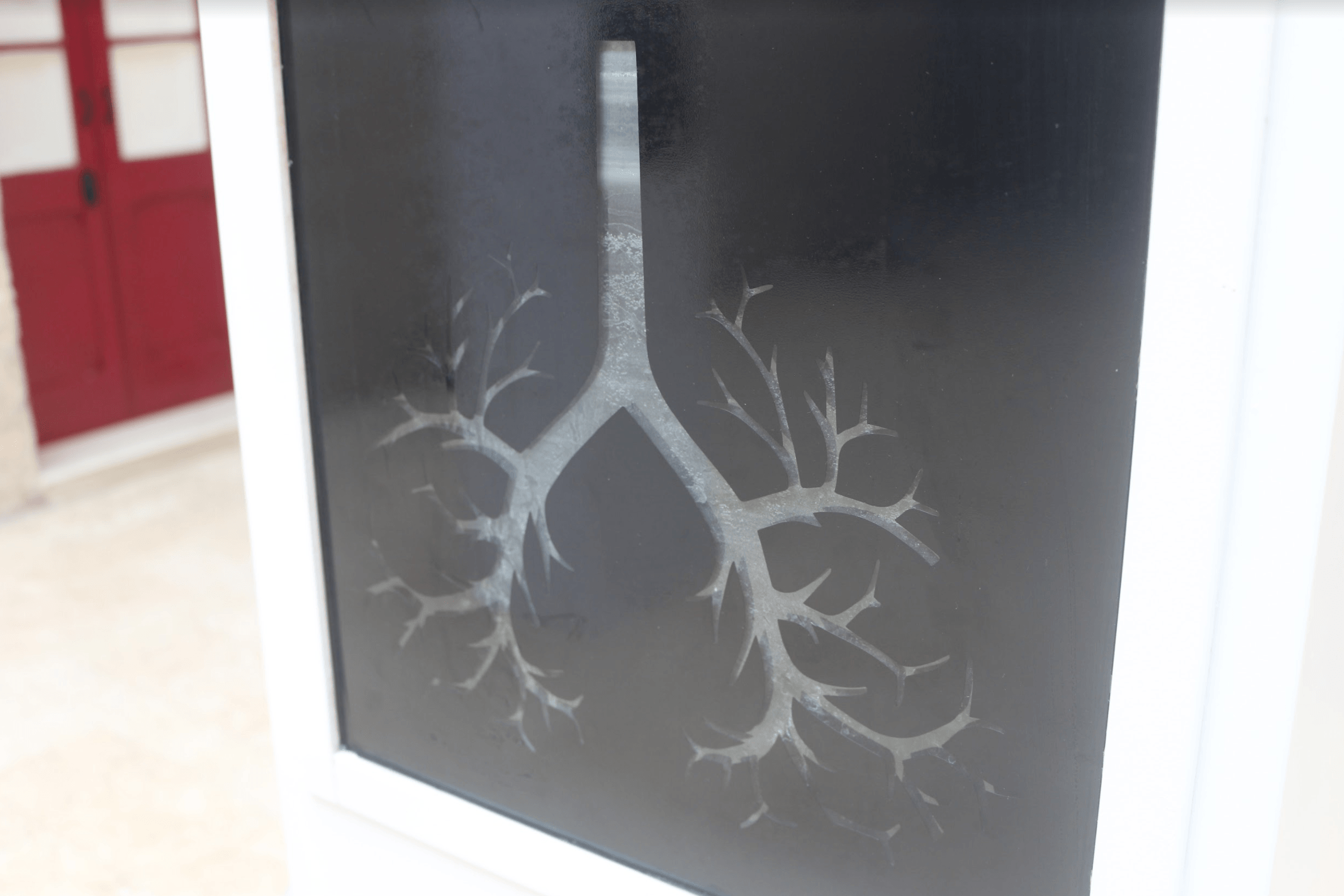

Nature has always been central to the context of the Deep Shelter project; it becomes ‘a metaphor of the self, where both fluidity and tension are captured.’ But it is

difficult for patients whose lives are punctuated by clinical sights, sounds, and smells to feel in tune with nature. With the help of her aromatherapy oils, Fleri brings in an element of nature and tactility to the patients. ‘The kind of experiences we are trying to create are aimed at making the patient feel contained and held,’ Baldacchino explains. ‘We want to provide something that supports their gritty journey towards acceptance. Even if it does not fit into what we traditionally think of as contemporary art, it fulfils the scope.’ She expresses her frustration with the art in spaces where people are undergoing medical treatment that is merely ‘decorative’ or ‘clever’, and does not provide any sustenance to the patient’s emotional well being. There has to be a story woven behind the artwork that leads one to feel understood when they are going through a time of change, upheaval, or trauma.’

Baldacchino, Chase, and Fleri have received both support and contempt about the project’s goal to derive value from art for the process of healing. However, the patients that the Deep Shelter project has treated are unequivocal about its benefits.

One patient says she believes the workshops serve to ‘release’ emotions, while supporting them throughout their different journeys. When she felt that she had nothing to lose, the artistic outlet Deep Shelter provided gave her a way to release the emotions of anger, fear, and regret she had been holding within for so long. ‘The health system needs to be more open to other therapies to be able to provide a truly holistic healing modality, incorporating mind and body and not seeing the person as ‘parts’.’

Humans are the only species on the planet with the ability to tell stories about their life through art and sensual expression. But during the cancer journey, it is harder to find yourself and your experiences reflected in a meaningful way. The Deep Shelter project seizes art’s potential as a means to process illness, pain, and trauma and puts that power into the hands of the people who need it most.

Author: Valletta 2018 Foundation