Conserving brushstrokes

A new conservation project will soon start work on one of Malta’s most significant historical artworks. Laura Bonnici meets Prof. JoAnn Cassar, Jennifer Porter, Dr Chiara Pasian, and Roberta De Angelis to find out why conserving the d’Aleccio Great Siege Wall Painting Cycle is of national importance.

Continue readingLuzzu Truths

Strolling along Malta’s coast, you’ll be mesmerised by the rainbow of traditional fishing boats ambling on the water—that and all the eyes ogling at you from their bows. Katre Tatrik takes a closer look at the hidden meaning behind the luzzu’s colours.

The Maltese luzzu dates back to the time of the ancient Phoenicians. For generations, Maltese fishermen have painted them in a kaleidoscope of bright colours, turning them into a national icon. But is there rhyme or reason to the hues they choose? Lifelong fishermen, brothers Charles (62) and Carmelo (70) from Marsaxlokk, paint their luzzus twice a year in bold blues, reds, and yellows. It’s no easy task, requiring thorough cleaning and six layers of paint. Despite their dedication, Charles and Carmelo, like many others, are largely unaware of the hidden meanings the colours on their boats carry. ‘They’re all the same,’ Carmelo says. ‘It’s just for beauty.’ Charles adds that ‘these boats have always looked the way they look.’

But in 2016, Prof. Anthony Aquilina from the University of Malta embarked on a project that would uncover more. ‘Contrary to what you have been told, there is a lot of meaning in the way our traditional boats are painted,’ he explains. Aquilina edited and published The Boats of Malta – The Art of the Fisherman, written by world-famous anthropologist Desmond Morris.

Morris resided in Malta for six years in the 1970s, visiting each of the fishing villages on the islands. During his stay, he sketched some 400 of the 700 traditional boats anchored in the coastal villages. He wrote: ‘to visit a Maltese fishing village is like entering a huge, open-air art exhibition.’

Summing up Morris’ work, Aquilina says that ‘even in a small country, you can see the difference between one locality and another. But at the same time, there is the individual stamp of the fisherman, of that particular person.’

To visit a Maltese fishing village is like entering a huge, open-air art exhibition.

Morris’ main findings show that some traditional rules come into play when choosing the colour palette for a luzzu.

Whilst reddish brown or maroon was typically painted on the lower half of the boat to mark the waterline, the locality of a boat’s owner could be identified by the colour of its mustaċċ. The mustaċċ is the band above the lower half of the boat, shaped like a moustache, which gives the feature its name. A red mustaċċ would indicate that the boat came from St Paul’s Bay, for example. A lemon yellow indicated a boat from

Msida or St Julian’s, whilst an ochre yellow one would identify the boat as hailing from the Marsaxlokk and Marsascala area. When a mustaċċ was painted black, it denoted mourning for a death in the family.

In addition to colours, decorations also send a message. In more than half of luzzus, signature eyes are painted on the bow or the stern—symbols of protection for fishermen out at sea. Where the eyes are not seen, other symbols such as a rising sun, a Maltese cross, fish, shooting stars, or lions are painted on. The gangway, usually varnished brown, can be heavily decorated or engraved with symbols of the sea and the island: shells, mermaids, birds, flowers. Religious insignia are common too, with doves, olivebranches, and lambs often making an appearance.

Political or religious influences also come into play where a luzzu’s name is concerned. During the time we spent in Marsaxlokk, we saw San Mikiel (Saint Michael the Archangel, patron saint of Isla), John F. Kennedy, and Ben Hur.

Even if Charles and Carmelo couldn’t tell us what the luzzu’s colours mean, their dedication to tradition is undeniable. Before we left, they said they were fearful that this part of Malta’s heritage may fade away as featureless carbon-fibre boats wade in. I hope they’re wrong.

Author: Katre Tatrik

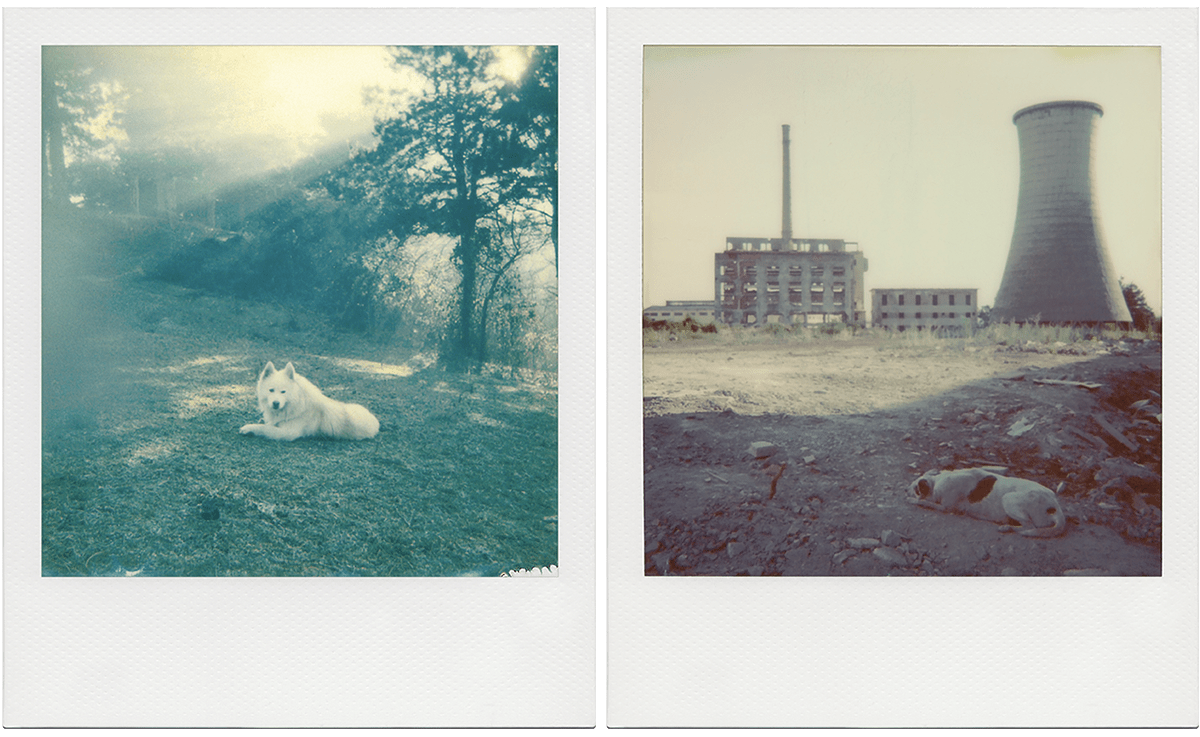

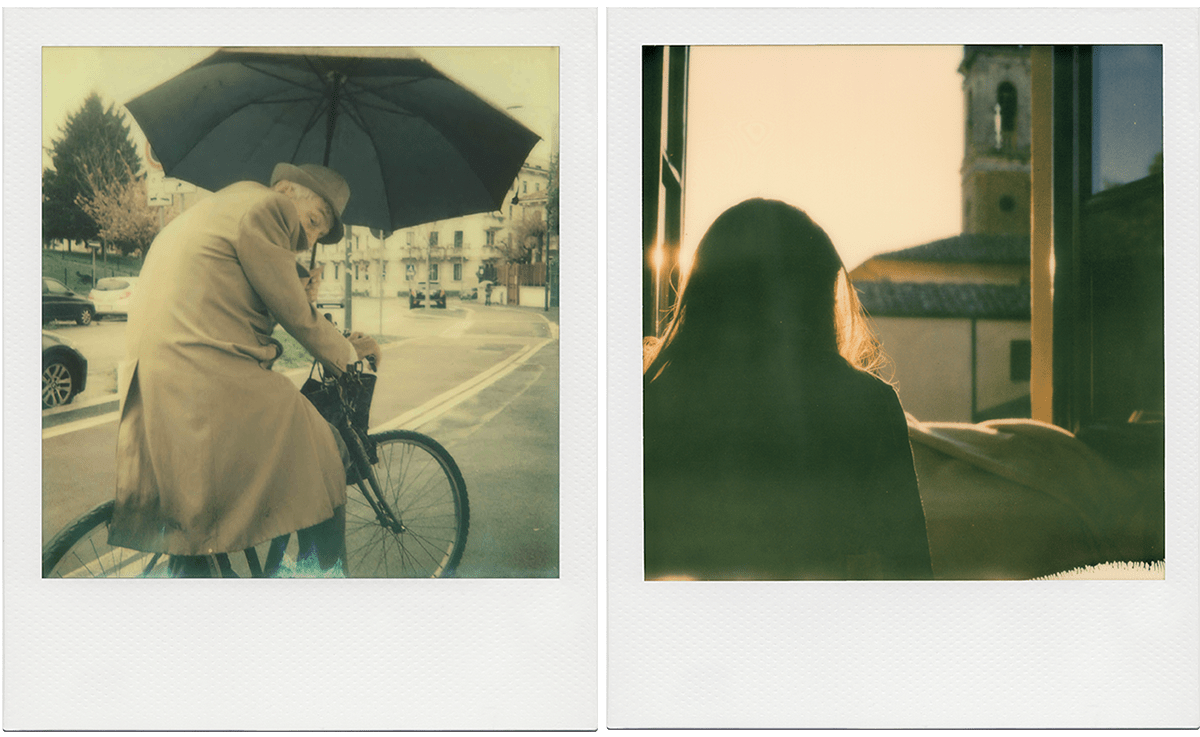

Instant Photography

Instant cameras, commonly referred to as ‘Polaroids’ thanks to the pioneering company, offer limited manual-automatic controls. These self-developing photographs present numerous analog imperfections, but additional aspects make them distinctive.

Polaroids do not document the world faithfully. They create a new version of it through their own lighting schemes, colours, and softness; a quality associated with past technologies. All these aspects enhance the transient nature of subjects, such as boy counting in during a game of hide-and-seek (see picture).

The process of capturing an image can also draw from ‘missed opportunities’. These are subjects one comes across but does not photograph due to not having a camera at hand, or for fear of intrusion. A line of people coming down a hill, or visitors waiting like purgatorial souls outside a derelict hospital—such images are captured in the mind and their essence might be transferred into other shots.

Having the image in hand within minutes does not necessarily make the medium of instant photography unique, for even the photos themselves can change hues and mood with time. What does make it unique is its unpredictability and the challenge it poses when it comes to materialising intentions within the limitations of the medium. This makes the effort worth pursuing.

An image illustrates the relationship between a subject and its viewer. It is a perspective on the world, be it a printed photograph, a digital file, or a memory.

Find out more about Instants, published by Ede Books, here: http://bit.ly/2yCQLyV

Article and photographs by Charlo Pisani

A generation game

Sharing memories, ideas, and feelings is something we usually do with friends. What if you were asked to do it with a stranger? And what if that stranger was ‘from a different time’? Active Age – Intergenerational Dialogue project creator Charlotte Stafrace has the answers.

Confrontation caricaturised

My work centres on the co-existence of dualities. It treads blurred borders and investigates uncertain divides between opposing poles. It synthesises extremities and acts as a seam that binds together disparate realities.

Uncertain of its own actuality, it questions its own being.

Artist statement

Prof. Vince Briffa peels back the layers of his latest works to reveal his thoughts on duality, confrontation and caricaturisation and how he translates them into art.

De-isolating an island scene

While the Maltese art scene continues to expand and mature, questions of relevance are coming to the fore: How does Maltese art travel? Is it as insular as we think? Nikki Petroni looks at current research to find answers.

Of art and interpretation

Interviewed by Prof. Raphael Vella, local artist Aaron Bezzina gives insights into what has shaped him and his work.

Drawing with our eyes

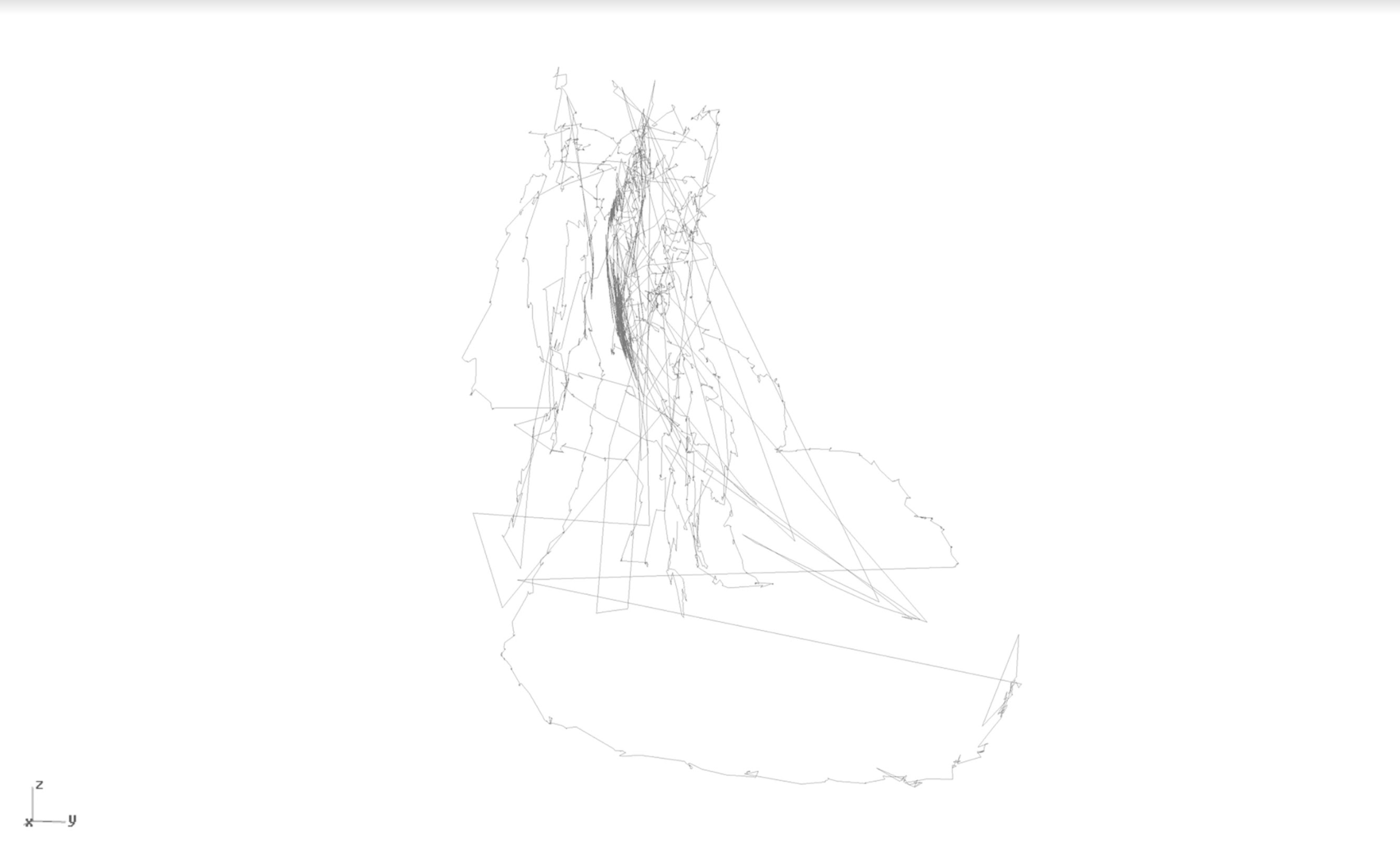

Drawing can be defined as the active exploration of an individual’s mental imagery. John Berger described it as ‘an autobiographical record of one’s discovery of an event—seen, remembered, or imagined.’

The initial hunch for my research revolved around the idea of drawing with one’s eyes instead of hands by using an eye-tracker.

The approach intrigued me for three reasons. It allowed me to explore the notion that an artist’s skills are in his tools—his hands. The eye-tracker-based technique ‘levelled the playing field’ between artist and non-practitioner by removing hands from the equation. Secondly, through eye-drawing practice, I could also notice a shift in the drawing methods used. Normal drawing involves hand-eye coordination and a degree of intuitive eye movements. In ‘eye-drawing’, these movements have to be suppressed into following contours along the observed worldview, while also restraining the impulse to refer to the accustomed curvilinear hand motions. All this feeds into the fact that eye-drawing cannot be regarded through the same approach as ‘normal’ drawing. Eye-drawn objects have a direct representation tied to their place and time of execution and acquire a technological aesthetic.

I explored these concepts in several experiments. I ran communal ‘life’ eye-drawing classes with first year students reading for an MFA (Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta [UM]). Their resulting visuals were surprisingly individualistic, highlighting their characters, a quality I observed to be constant throughout all eye-drawings.

Using an eye-tracker to draw led to some exciting possibilities. I tested a preliminary algorithm, developed by my colleague Neil Mizzi, (Faculty of ICT, UM) that ‘corrected’ an eye-drawing by comparing it to a real-world picture. The technique could be applied in future eye-drawing devices designed to help physically impaired individuals to draw from real-world images using just their eyes.

It can be argued that art is a subjective experience, both in its creation and perception. Eye-drawing can exploit this subjectivity revealing ‘signature’ gestures through a new way of looking.

This research was carried out as part of a Masters by research at the Department of Digital Arts, Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta (UM).

Author: Matthew Attard

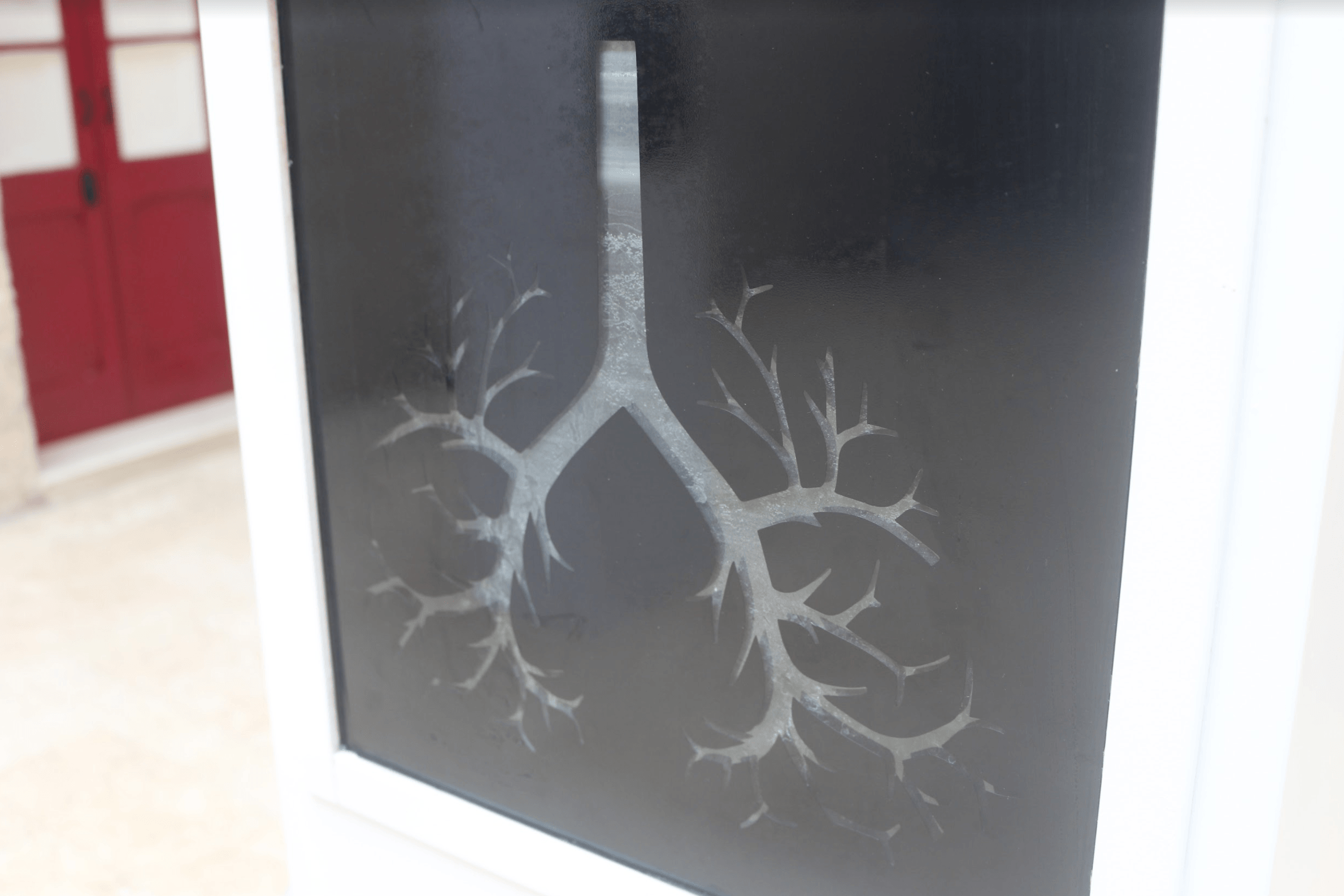

Onfoħ

Breathing moves air in and out of the lungs. Oxygen goes in, carbon dioxide is flushed out. An exchange occurs within our internal environment. Onfoħ is an installation that explores the phenomenon of carbon emissions through human respiration.

Carbon emissions are loosely defined as the release of greenhouse gases and their precursors into the atmosphere over a specified area and time. This notion is usually linked to the burning of fossil fuels like natural gas, crude oil, and coal. In short—human activity.

From the very beginning, humans have altered their environment. In fact, an average person takes 12 to 20 breaths per minute, amounting to an average of 23,040 breaths per day. The world’s population collectively breathes out around 2500 million tonnes of carbon dioxide each year, around 7% of the annual carbon dioxide tonnage produced by burning fossil fuels.

Although the carbon dioxide produced through breathing is part of a closed loop in which our output is matched by the input from the food we eat, it can be used as a metaphor to visualise other unseen outputs from other man-made sources: transportation, electricity, heating, water consumption, food production.

Onfoħ was designed to engage citizens and address an overwhelmingly challenging environmental problem of our time—our inability to visualise our own carbon footprint. The work does this by showing that which is usually unseen—the physical manifestation of carbon emissions.

The installation consisted of five plinth-like structures, each housing a glass container of lime water. Stencilled onto the pillars were illustrations of lungs, each consecutive pair having decreased surface areas, conveying a sense of degeneration. When the audience interacted with the installation, breathing into the lime water and adding carbon dioxide, they triggered a chemical reaction that produced insoluble calcium carbonate. The clear solution turned milky, making the invisible visible.

Humans contribute constantly to carbon-based, hazardous waste production, and the installation demanded that they face that reality.

Note: The installation was displayed as part of a collective exhibition entitled Human Matter, hosted by the Malta Society of Arts at the end of last year. David Falzon, Matthew Schembri and Annalise Schembri teamed up to work on this artwork as soon as they finished reading for an MFA in Digital Arts (Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta).