Bursting the RRI bubble

Relationships are based on trust, communication, and mutual respect. The same can be said of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI). Behind all the new ideas, it all boils down to a group of people, hailing from different walks of life, coming together to try and create a better future for everyone. At the fourth annual NUCLEUS conference, researchers, academics, science communicators, creatives, and business people flocked to the tiny isle of Malta to share their stories and attempts to embed RRI into their institutions and communities. As everyone settled in, dialogue flowed among delegates and the room was abuzz. University of Malta pro-rector Prof. Godfrey Baldacchino opened the conference with a question: How similar are universities and Valletta, the fortified capital that was hosting the conference? Having been constructed following Malta’s infamous Great Siege, the Knights encased Valletta in massive bastions, allowing only four small entry points. ‘Valletta is an island on an island,’ Baldacchino said. ‘Are universities the same? Are we trying to protect our own?’ The question had many heads nodding in response.

Most people in the room expressed a feeling of obligation to render knowledge more accessible, more relevant, and more digestible to a wider audience. But they encounter a myriad of challenges. Engaging with publics or policy makers isn’t easy. It means addressing different needs in different ways, sometimes even pandering to whims and flights of fancy. Most people noted issues with time, funding, and resources, calling for processes to be formalised. Others pointed to a lack of creative skills and, sometimes, general interest across the board. What also quickly emerged was frustration with the term RRI itself, creating confusion where there needn’t be any.

With all of these difficulties, however, came solutions. Dr Penny Haworth from the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, said that in her experience ‘we need to look at what universities are already doing and work smart. Win hearts and minds.’ University of Malta’s Nika Levikov also pointed out that ‘there are a lot of people practicing RRI who are not conscious of it.’ And for those who do not believe it to be a priority, for those who do not want to engage? ‘You have to set them aside and show them it is possible in a way they understand,’ says Zoran Marković from MISANU, Serbia.

Picking up Baldacchino’s thread on bringing down the walls of universities and research institutions, Dr Annette Klinkert from Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences in Germany summed up her main takeaway from all the discussions. ‘What we can learn here is that it’s time to burst the bubble in which we work. Especially this field of RRI. It is time to leave our cosy little community with our results.’ The results are the various projects that NUCLEUS has been championing over the past years, bringing research to its audiences. ‘All the projects are useless if they can’t merge and get out [into society and communities],’ she emphasises. ‘If they don’t merge, they’re pointless. It is time to burst the bubble.’

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Pushing for Malta’s industrial renaissance

With all the cranes strewn across the Maltese landscape, it appears that the construction industry is one of Malta’s primary economic drivers. But there are other, less polluting ways of generating income. Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi discusses MEMENTO, the high-performance electronics project that could pave the way for a much-needed cultural shift in manufacturing.

Continue readingThe sky’s role in archaeology

In 1994, Czech poet-president Vaclav Havel wrote an article discussing the role of science in helping people understand the world around them. He also noted that in this advance of knowledge, however, something was left behind. ‘We may know immeasurably more about the universe than our ancestors did, and yet it increasingly seems they knew something more essential about it than we do, something that escapes us.’ Almost all traditional cultures looked to the sky for guidance. Cosmology is what gave our ancestors their fundamental sense of where they came from, who they were, and what their role in life was. While arguably incorrect, these ideas created codes of behaviour and bestowed a sense of identity. The cosmology of European prehistoric societies has been studied independently by archaeologists and archaeoastronomers (an interdisciplinary field between archaeology and astronomy). Despite their shared goal of shedding light on our past lives, thoughts, and ideas, the two fields have often failed to merge, mainly due to different approaches. A clear local case is the question of the Maltese megalithic temples.

The Mnajdra South Temple on Malta predates both Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids. It is the oldest known site in the world that qualifies as a Neolithic device constructed to cover the path of the rising of the sun throughout a whole year. What is unfortunate is that, so far, archaeologists and archaeoastronomers have studied the site largely in isolation.

Whether the temples were built to visualise the effects of the rising sun as seen today is an open question. But with such specific and repetitive patterning, one cannot deny that the sky was an important element in the builders’ understanding of the world—their cosmology.

With some exceptions, archaeologists have largely ignored, excluded, or underrated the importance of the sky in the cultural interpretation of the material record. When studying ancient communities, chronological dating and economic concerns are often given precedence over the immaterial.

But the fault does not lie solely with disinterested archaeologists. Archaeoastronomy has often been too concerned with collecting astronomical and orientation data, neglecting the wider archaeological record, and ignoring the human element in cosmology.

We need to find a common ground. Both sides need to open themselves up to different professional perspectives and convictions and embrace alternative interpretations and possibilities. Bridging the gap between archaeology and archaeoastronomy will allow us to paint a detailed picture of past societies. And maybe it will shed light on that lost knowledge about the universe and our place in it.

Lomsdalen and Prof. Nicholas Vella are organising an afternoon workshop on Skyscape Archaeology as well as an open symposium on Cosmology in Archaeology. For more information, visit: um.edu.mt/arts/ classics-archaeo/newsandevents

Author: Tore Lomsdalen

Kidney Stakes

A small team of scientists at the University of Malta is trying to determine what causes children to be born with serious kidney defects. Laura Bonnici speaks to Prof. Alex Felice, Dr Valerie Said Conti, Esther Zammit, and Alan Curry to find out more about this ground-breaking programme.

‘I’d sell a kidney for that!’ Most of us have been guilty of using this expression when faced with something desirable. But do we fully appreciate the real value of what we are offering before the words escape our lips?

Kidneys are our body’s official waste disposal system, filtering out toxic build-up from our blood, which can poison us if left unchecked. With kidney failure posing such a threat, renal research has become an ongoing global goal.

A team of scientists from the University of Malta is currently honing in on what may cause children to be born with ‘CAKUT’, or Congenital Anomalies of the Kidney and Urinary Tract.

With between three and six cases recorded per 1000 live births worldwide, CAKUT is the most common cause of end-stage kidney disease in children. Since early identification of these anomalies may reduce kidney damage later in life, the LifeCycle Malta Foundation has raised funds for a renal research programme which targets CAKUT and its causes.

‘We know that a number of children are born with a kidney defect, but in many cases, we are not sure why,’ explains the programme’s principal investigator, Dr Valerie Said Conti . ‘There are many factors that can affect the development of the kidney, both genetic and environmental. We are trying to understand those influences so that we can carry out preventative strategies, diagnose issues earlier, and target personal therapeutic interventions.’

A number of children are born with a kidney defect, but in many cases, we are not sure why.

For this team of renal researchers, the first three years of initial research has been the first step in a far longer journey. ‘We hope to contribute our data to the international literature pool,’ continues Prof. Alex Felice, consultant and supervisor on the programme. ‘We will need a massive amount of data to create a robust theory with which to progress. We hope that our findings regarding CAKUT will be useful when we come to the stage of creating new interventions.’

It’s an end-game that has kept the small team focused as they approach the programme’s expected completion date this year. Having had to start literally from scratch, they collected biological samples from patients with a range of kidney diseases, including CAKUT, nephrotic syndrome, and Bartter syndrome. This allowed them to build the renal disease collection at the Malta BioBank, a vital storehouse for scientists.

‘For research projects like this, you see what material is available and you work with it,’ explains Said Conti . ‘A big part of it so far has been sourcing the samples from families attending the clinic with their formal consent for the material to be used in this project. We are hugely grateful to those who accepted to take part in the research. Without them, it would have been impossible.’

This project has set the groundwork for renal research in Malta to continue. ‘Without funding, projects such as this one simply could not exist,’ Said Conti remarks of the €100,000 donation LifeCycle Malta Foundation made to RIDT. ‘It enabled us to employ a full-ti me Research Support Officer, involve other laboratories, attend international meetings to share insights, perform ultrasound tests, and invest in ‘Next Generation DNA Sequencing’, genetic technology that maps out genes, revolutionising our world.’ But there is much more to come.

The Founder of the LifeCycle Malta Foundation, Personal Fitness Consultant Alan Curry, agrees. ‘Renal failure is an ever-increasing problem with figures going up every year, and LifeCycle is the only NGO that is actively supporting renal patients and their families in Malta. Our annual LifeCycle Challenge, which this year is routed from Dubai to Oman, aims to raise €150,000. It’s a huge responsibility, but we are sure that, by funding research programmes such as this, we will significantly improve the lives of kidney patients.’

Author: Laura Bonnici

Eat your way to a healthy life

With growing evidence showing that our eating habits affect not only our waistline, but our physical and mental health, should we all be turning to the Mediterranean diet to live longer, healthier lives? Prof. Giuseppe Di Giovanni, Prof. Christian Scerri, and Dr Paulino Schembri write.

Continue readingAccidental science

Do scientists need to have a clear end-goal before they dive down the research rabbit hole? Sara Cameron speaks to Dr André Xuereb about the winding journey that led to the unintended discovery of a new way to detect earthquakes.

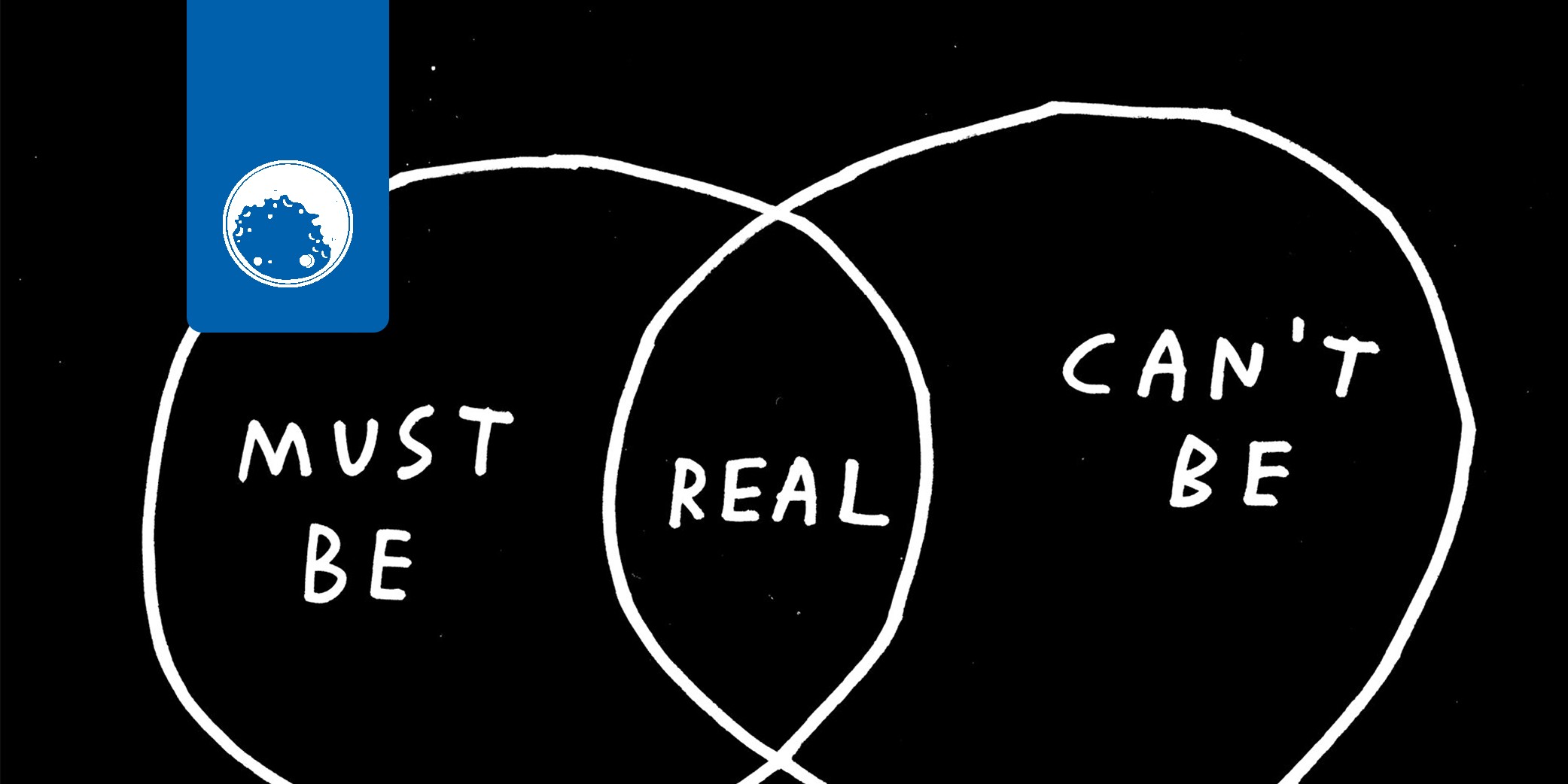

Some of science’s greatest accomplishments were achieved when no one was looking with a purpose. When studying a petri dish of bacterial cultures, Alexander Fleming had no intention of discovering penicillin, and yet he changed the course of human history. Henri Becquerel was trying to make the most of dwindling sunlight to expose photographic plates using uranium when he stumbled upon radioactivity. A chance encounter between a chocolate bar in Percy Spencer’s pocket and the radar machine that melted it sparked the invention of the household microwave.

One would think that with this track record of coincidental breakthroughs, the field of science and research would continue to flourish by embracing curiosity and experimentation. But as interest piques and funding avenues pop up for researchers, there has been a shift in mindset.

Money changes things. And while it does allow people to work hard and answer more questions, it has also fostered expectations from stakeholders. Investors want fast results that will improve their business or product. We, the end-user, want to see our lives changed, one discovery at a ti me. We’re no longer satisfied with research for research’s sake. At least for the most part.

Quantum physicist Dr André Xuereb (Faculty of Science, University of Malta) is all too aware of this issue and its effects on scientific progress. Xuereb explains scientists’ frustration: ‘A lot of funding, in Malta and elsewhere, is dedicated to bringing mature ideas to the market, but that is the ti p of the iceberg. There is an entire innovation lifecycle that must be funded and sustained for good ideas to develop and eventually become technologies. The starting point is often an outlandish idea, and eventually, sometimes by accident, great new technologies are born,’ he says.

STARTING POINTS

Over the past few years, Xuereb has been exploring new possibilities in quantum mechanics.

The field of quantum mechanics attempts to explain the behaviour of atoms and what makes them. Its mathematical principles show that atoms and other particles can exist in states beyond what can be described by the physics of the ordinary objects that surround us. For example, quantum theorems that show objects existing in two places at once off er a scientific basis for teleportation.

Star Trek fans know exactly what we’re talking about, but for those rolling their eyes, the reality is that many things in our everyday lives wouldn’t exist without at least some understanding of quantum physics. Our computers, phones, GPS navigation, digital cameras, LED TV screens, and lasers are all products of the quantum revolution.

The starting point is often an outlandish idea, and eventually, sometimes by accident,

great new technologies are born

Another technology that has changed the way we live and work is modern telecommunications technology. When you pick up your phone to message a friend overseas, call a loved one, or email a colleague, telecoms networks spanning the earth carry the data across continents and under oceans through thousands of kilometres of optical fibres.

The 96-kilometre submarine telecommunication link between Malta and Sicily was Xuereb’s focus in 2015. He organised a team of European experts to begin investigating the potential for building a quantum link between the two countries.

The Austrian, Italian, and Maltese trio were particularly interested in a strange property called ‘entanglement.’ This is a curious property of quantum objects that can be created in pairs of photons, connecting them together. This entanglement can be distributed by giving one of these photons to a friend and keeping the other for yourself, establishing a quantum link between you and this friend—an invisible quantum ‘wire,’ so to speak.

Through this connection, you and your friend can send data faster than over ordinary connections; by modifying the state of the photon at your end, you can instantly affect the state of your friend’s photon, no matter how far apart you are in the universe. Using quantum links such as these, all manner of feats can be performed, including super-secure communications. ‘We wanted to demonstrate that quantum entanglement can be distributed using a 100km-long, established telecoms link, using what was already available, with no laboratory facilities in sight,’ explains Xuereb. His team also wanted to demonstrate that entanglement using polarisation of light was possible. Previously it was thought impossible in submarine conditions, even though it has some very technologically convenient properties.

Two years and several complex experiments later, Xuereb and his team have indeed proven the possibility of quantum communications over submarine telecommunication networks. And with one question answered, a slew more lifted their heads.

The Italian subteam, led by Davide Calonico (Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica, INRIM), now turned their attention to a different set of questions for the Malta-Sicily telecommunication network.

MORE TO COME…

Atomic clocks keep the world ticking by providing precise timekeeping for GPS navigation, internet synchronisation, banking transactions, and particle science experiments. In all these activities, exact timing is essential.

These extremely accurate clocks use atomic oscillations as a frequency reference, giving them an average error of only one second every 100 million years. Connecting the world’s atomic clocks would create an international common time base, which would allow people to better synchronise their activities, even over vast distances. For example, bank transactions and trading could happen much faster than they do at present.

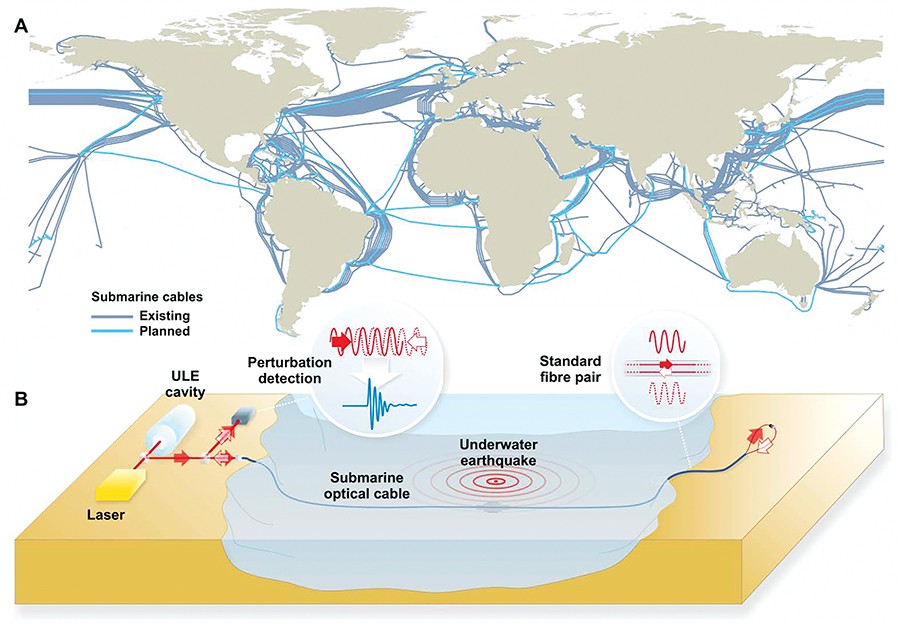

This can’t be done by bouncing signals off of spaceborne satellites, since tiny changes in the atmosphere or in satellite orbits can ruin the signal. This is where the fibre-optic network comes back into the picture. Researchers have recently been looking at the telecoms network as a way to make this synchronisation possible. Scientists can use an ultra-stable laser to shine a reference beam along these fibres. Monitoring the optical path and the phase of the optical signal of the beam can then allow them to compare and synchronise the clocks at both ends.

Whilst Calonico and his team were testing this idea on the submarine network between Malta and Sicily, a few thousand kilometres away, meteorology expert Dr Giuseppe Marra was monitoring an 80km link in England. On October 2016, everything changed. One night, he noticed some noise in his data. Unable to attribute the noise to misbehaving equipment or a monitoring malfunction, his gut told him to turn to the news from his home country, Italy. There, he saw that the town of Amatrice had been devastated by an earthquake of 5.9 magnitude.

Further testing confirmed that the waveforms Marra saw in the fibre data matched those recorded by the British Geological Survey during the earthquake. His system even recorded quakes as far away as New Zealand, Mexico and Japan. This was huge news.

In simple terms, the seismic waves from an earthquake tremor cause a series of very slight expansions and contractions in fibre-optic cables, which in turn modify the phase of the cable’s reference beam. These tiny disturbances can be captured by specialised measurement tools at the ends of the cable, capable of detecting changes on the scale of femtoseconds: a millionth of a billionth of a second.

The majority of seismometers are land-based and so small that earthquakes more than a few hundred kilometres from the coast go undetected. Conventional seismometers designed to monitor the seabed are expensive and don’t usually monitor underwater seismic activity in real time. Telecoms networks could offer a solution that would allow us to observe and understand seismic activity in the world’s vast oceans. They would open up a new window through which to observe the processes taking place underneath Earth’s surface, teaching us more about how our planet works. In future, it may even make it possible to detect large earthquakes that cause untold devastation earlier.

The beauty of this discovery is that the infrastructure already exists. No new work is needed. All that is required is to set up lasers at either end of these cables, using up a tiny portion of a cable’s bandwidth without interfering with its use.

THREADS COMING TOGETHER

Marra got together with Xuereb and Calonico, who were already working on the undersea network between Malta and Sicily, to conduct some initial tests. The underwater trial, published in the world-leading journal Science this year along with the terrestrial results, was able to detect a weak tremor of 3.4 magnitude off Malta’s coast. Its epicentre was 89km from the cable’s nearest point, which reinforced the idea that cables can be used as a global seismic detector. ‘We would be able to monitor in real time tiny vibrations all over the planet. This would turn the existing network into a microphone for the Earth,’ Xuereb explains.

If we don’t fund the initial few steps of the innovation lifecycle,

how will we ever develop new technologies?

The system hasn’t been tested on an ocean cable. An interesting target would be a cable that crosses the mid-Atlantic ridge, where the drifting of Eurasian and African tectonic plates creates an area of high seismic activity. Based on the results so far and on conservative assumptions, trials are being planned for the near future on a larger scale, which will give us a better idea of the possibilities.

FURTHER DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE…

In many ways, it is understandable that agencies that fund science favour smaller, more goal-driven research programmes. They seek tangible results in a timely manner to reap quick rewards. But as this story goes to show, a change in mentality is needed.

‘If we don’t fund the initial few steps of the innovation lifecycle, how will we ever develop new technologies? This is a problem that affects scientists from many countries and comes from a mismatch in timescales. A year is a long time in politics, but a decade is often a short time in science,’ Xuereb comments.

Innovation has to start from somewhere, and it often starts from ideas which may have no apparent relevance to our everyday lives. We need to support researchers by keeping an open mind to unknown long-term possibilities—or the world might not only miss the next earthquake but also the next life-changing discovery.

Author: Sara Cameron

English for medicine: Bridging worlds

You come to Malta to attend Medical School, and you end up in an English class. Nicola Kirkpatrick talks to Dr Isabel Stabile, Omar N’Shea, and Edward Wilkinson about the often unappreciated value of the University of Malta’s Medical Foundation Programme and its impact on international medical students’ lives.

A sea of blank faces stared him down. Omar N’Shea had asked his students a question, but no reply came. None of them wanted to be there. The University of Malta’s Medical Foundation Programme (MFP) aims to equip high school graduates with less than 13 years of formal education with the skills they need to enter Medical or Dentistry school. But its focus on academic English is what receives the most ire. N’Shea, one of the programme coordinators, understands. ‘They don’t see the value initially. They think to themselves: ‘I didn’t travel thousands of miles away to sit in an English class. No, I want to study medicine.’ The frustration is understandable,’ he nods.

But when so many international students were struggling with the medical course due to language and communication difficulties, something clearly had to be done.

Looking back at the challenges she was facing when the Medical School opened its doors to international students, Director of Studies Professor Isabel Stabile notes the discrepancy in language skills. What was expected was quite distinct from the reality of the situation. ‘What is interesting about our student body is that their spoken level of English is really high,’ says N’Shea, ‘but their written level of English needs work to keep up with the demands of an academic course.’

English Programme Coordinator and tutor Edward Wilkinson agrees, highlighting that ‘resources were lacking. Teaching exercises and materials were sourced online and everyone did the best they could. But a gap quickly emerged as far as Medical English was concerned.’ Stabile further clarifies, ‘Most books available were aimed at teaching doctors and nurses bedside manner and care for patients, but there was little to none out there that focused on academic medical English.’

With this philosophy in mind, Stabile, N’Shea, and Wilkinson joined forces to develop a series of books called Academic Medical English for Pathway/Foundation Programmes. These books provided a framework for students to deal with the language in which scientific subjects are taught. The material improves their academic literacy in ways important to medical students, equipping them with skills such as reviewing research papers, writing reflective essays, and answering essay questions.

The book was ‘born out of the needs of these students and the medical program,’ says N’Shea. ‘The concept is to present to the students the core skills required by the medicine and surgery degrees, so that students become aware of the differences between using English as a lingua franca and using English within the framework of academic literacy.’ To enable this, the team included topics to reflect those covered in the science classes that students attend throughout the course. ‘So if they’re doing pulmonary topics in science classes,’ N’Shea says, ‘then they’re discussing them in English classes too. We used the science as a framework for our English lessons, and that was essential. Rather than teaching two disciplines with no dialogue, we created a bridge.’

This approach saw immediate shifts in perception. Dr Hussein Alibrahim, now a house officer in Kuwait, says his primary and secondary education was all in Arabic, and the foundation course, where English and science stood side by side, ‘was an advantage and a necessity. Skimming carefully through an article, identifying keywords, summarising, criticising, asking questions, and looking for the right answers are all skills that I learned for the first time in the foundation course and are skills I still use today,’ he added.

But the programme was not only useful for medical school. Alibrahim noted how it changed his day-to-day life as well. It taught him important lessons on punctuality and work ethic. ‘If you don’t learn [these things in foundation school] then maybe you’re in the wrong place,’ he notes.

With time, the team refined the course. After looking into the discrepancy between spoken and written levels of English, N’Shea and Wilkinson determined that the most probable reason behind it was a lack of reading by the students. Due to this, reading is now a core element of the course and is based on science topics to keep students’ interest piqued.

Now that the coursework has been implemented, positive results can already be seen. Students are so ready and raring to go that ‘sometimes they even want to take over the sessions,’ says N’Shea. ‘A student came up to me in class one time and asked to explain a concept to the others. It was such a dramatic shift.’ This has made it a joy to be in class, he adds, saying that ‘it became an active classroom. Students are totally immersed now.’ He feels that, through this course, the students are empowered ‘because they feel they can bring into the classroom all the things they know from science, but explore them through language.’ This way, ‘English is presented as a skill set to enable them to better achieve their goal in the career path of choice. It makes English less of an extra subject and more of a tool,’ he adds.

N’Shea, Wilkinson, and Stabile all agree that they will continue to perfect the programme. Currently in the works is a coursebook dedicated to developing listening skills. It will concentrate on areas such as note writing and identifying and differentiating words even when people speak with different accents. However, before the ‘listening book’ (as they fondly call it) is released, we will see the ‘reading book’, which will provide scientific passages for the students to read and be assessed on. All editions of this book will have the added bonus of a teacher’s book, meaning that the coursework can be taught by any teacher around the world, even if their knowledge of science is lacking.

With students communicating more, isolation is less of an issue and this is immensely beneficial. ‘We have to remember the dramatic shift that these students are going through,’ Stabile says. ‘They’re moving country, dealing with culture shock, all while fending for themselves for the first time in their lives, an adjustment local students do not need to make.’ This, along with the pressure that comes with a course you only get one chance to pass, is significant.

With students communicating more, isolation is less of an issue and this is immensely beneficial.

The fruit of their hard work is evident. According to research conducted by the team, between 2008 and 2015, 86% of MFP graduates progressed through Medical School. Moreover, the proportion of MFP students who repeat Year 1 of their medical degree is only 8.2% compared with 8.8% for EU (mostly British) students between 2014 and 2017. They also found that MFP students who started in 2010 and graduated medical school in 2015 achieved the same average grade over the whole five years as did local students in that cohort.

That said, all this work is not just about grades. Stabile says the team’s intentions go beyond seeing students pass exams. What they want to do is to ‘place them on a trajectory for success.’ And that is definitely a goal they are achieving, one year at a time.

Author: Nicola Kirkpatrick

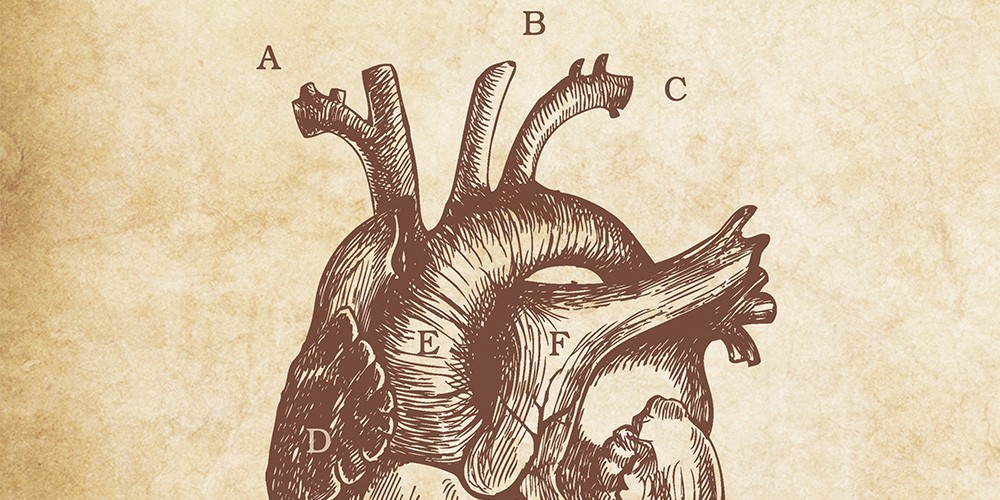

Aspirin and Cancer

Aspirin is often considered a wonder drug due to its versatile use in treating inflammation, reducing pain, and helping to prevent heart-related disease. However, there is more to it. Aspirin is actually cancer-preventive. Studies have shown that a daily low dose of aspirin, medically prescribed for more than five years, lowers the risk of cancer-related deaths by at least 30%. So, should we all start taking aspirin on a daily basis to lower our chances of getting cancer?

No, not exactly. This is because many aspects of aspirin’s cancer-preventive effects are still poorly understood. Particularly, researchers have not yet pinpointed what enables aspirin to selectively kill early-stage cancer cells and not healthy cells. This is the scope of the research currently being carried out at the Yeast Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Laboratory (headed by Prof. Rena Balzan).

The secret behind aspirin’s tendency to kill certain cells but not others seems to lie in the physiology of the exposed cells. Aspirin exploits the natural differences between healthy and cancerous cells to eliminate malignant cells before they can take over.

Oxygen, if transformed into ‘Reactive Oxygen Species’, is known to cause DNA mutations that can lead to cancer. Through this research, we studied mutated yeast cells which are a relevant model of early-stage cancer cells due to their low tolerance to oxygen-associated stress. We then identified genes in these mutant yeasts which are affected by aspirin.

One of aspirin’s targets is a key metabolite required for the production of energy-rich compounds vital for cell survival. We found that aspirin creates a shortage of this metabolite in mutated yeast cells, causing them to run out of energy and die.

This implies that early-stage human cancer cells may suffer a similar fate and, more importantly, partly explains how aspirin prevents tumour formation. Such knowledge may prove useful in the development of novel anti-cancer treatments.

This research was carried out as part of Project “R&I-2015-001”, financed by the Malta Council for Science & Technology through the R&I Technology Development Programme. This research is being carried out as part of Azzopardi’s Ph.D. project at the Centre for Molecular Medicine & Biobanking and the Department of Physiology & Biochemistry, University of Malta

Author: Maria Azzopardi

Chasing the white whale: the pursuit of sustainable tourism in Malta

EcoMarine Malta’s boat tours are leading the way in environmentally sustainable tourism around the Maltese Islands. Founder Patrizia Patti talks to Edward Thomas about how economic success doesn’t need to be sacrificed in order to protect nature.

Aquarter of Malta’s GDP comes from the tourism industry. It accounts for €2 billion annually and shows no sign of slowing down. Tourist expenditure went up by 13.9% from 2016 to 2017 alone. It constitutes one in every seven jobs in the local economy and maintains a close link to development: better hotels, improved roads, more diverse shops and restaurants. Beyond the economic benefits, tourism promotes and celebrates local customs, food, traditions, and festivals, creating a sense of civic pride.

However, there are concerns. In July and August, Malta, Gozo, and Comino are covered by thousands of holiday-makers flocking in. This is a not only a burden on already strained island resources and infrastructure including water, waste management, and traffic congestion, but it pushes many coastal habitats and aquatic ecosystems to the breaking point, with drastic impacts on local biodiversity.

Marine biologist Patrizia Patti laments how ‘people go with speed boats to Comino carrying beers, drinking, throwing bottles into the sea, playing loud music… it disturbs everything.’ If larger tour companies made a small effort to be more responsible, it could have a large effect, she says. ‘Even a simple announcement on a microphone, reminding people they are in a protected area and to behave in a certain way, advising people to respect nature, would help. It’s only a small reminder but it would help a lot.’ Always looking to lead by example, and to show that small actions can have a great impact, Patti set up EcoMarine Malta. The start up organises responsible boat tours around the island, where the international code of conduct is followed and people can experience the joy of encountering dolphins, turtles, and seabirds in their natural habitat.

FACE TO FACE

Patti says their goal is to establish profound personal connections between people and the sea in the hopes that it will change behaviour. She has been passionate about marine biology since the age of 17, when she first encountered a dolphin. That happened during a school trip to an aquarium. She says ‘it was exciting because it was the first time I saw a dolphin, but it was terrible seeing it trapped in a small tank. It made me so sad.’ The emotional response was strong enough to move Patti to tears. ‘It was at that point I decided I wanted to become a marine biologist. I wanted to help.’

Patti went on to study the ecology of sperm whales in the Ligurian Sea before travelling far and wide, gaining experience working with marine mammals in Canada, the Maldives, and the Red Sea. In 2013, she cofounded Costa Balenae Whale and Nature Watching in Italy, a company, like Eco Marine Malta, which strongly focuses on bringing humans closer to marine wildlife, forming lasting memories that inspire them to consider their environmental impact and educating both children and adults about the natural biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea.

How can you love something and want to protect it when you’ve never seen it?

Seeing these animals and experiencing their natural environment first hand is vital to establishing an emotional bond. This is what then engages people and inspires them to change their behaviour. ‘How can you love something and want to protect it when you’ve never seen it?’ Patti questions. By opening local and tourists’ eyes to the majesty of indigenous species, EcoMarine Malta create compassion and motivate people to take responsibility for the environment too. They also chip away at the sense of helplessness many feel when it comes to ‘actually making a difference.’ EcoMarine Malta provide education and information for their passengers to follow. Patti, who leads the tours herself, goes into how they can enjoy Malta’s beaches responsibly and sustainably, empowering them to take ownership for their actions and decisions before it’s too late.

MONEY PROBLEMS

It’s not always been plain sailing for EcoMarine Malta and their boat trips. Patti firmly believes that environmental conservation can be a tool to increase economic growth and employment in Malta. ‘Even if we act like an NGO, we decided to be a private company

because we want to create job places and grow and be able to provide the best service possible,’ Patti says. But not everyone agrees. Patti has received plenty of push back from others in the field as she lobbies for best practices to be enforced around the islands.

Some views are severely narrow and short-sighted, rooted in the belief that any sort of restriction of operations is bad, even if inspired by respect and protection for the natural resources they use. ‘People have to understand that a protected area is to enjoy for a long time. Maybe not now, maybe for one or two years you have to be careful, you can’t do everything you want to do. But after those two years, you can enjoy a new beautiful area, rich in life,’ explains Patti. Setting up EcoMarine Malta as a for-profit enterprise to prove these people wrong, however, has led to another kettle of fish. Because they’re not an NGO, applying for sponsorship and funding is a major challenge. Potential benefactors often dismiss collaboration, telling Patti that the company should be able to support its own endeavours.

This lack of support saw EcoMarine Malta having to rent boats from various charter companies, a massive expense. Externally renting a boat brought with it uncertainty and inflexibility. Last-minute dropouts or weather changes forced them to cancel tours and lose a lot of money. ‘The boat rental still had to paid for,’ she says. But things are looking up. EcoMarine Malta purchased their own boat this summer, and Patti is working hard on getting all the permits in place to have it out on the water as soon as possible. ‘Now we will be able to plan our own routes and diversify the tours we offer. At the moment, we have six tours available to choose from, including a sunset tour when marine life is at its most active,’ she smiles.

GET THEM YOUNG

2018 might be EcoMarine Malta’s first full summer season, but that doesn’t stop Patti from dreaming big about their future. She and her team want to do more outreach and education and are working on offering a series of courses for students aged between 10 and 16 years old. These children will be able to participate in a day of hands-on classroom activities, discovering and learning about sustainability and the ecosystem of the Mediterranean, followed by a boat trip to implement their new knowledge, observing and identifying the variety of wildlife and nature surrounding them and their island. ‘We hope to inspire a whole new generation of marine biologists and environmental scientists,’ Patti says.

With an army of environmentalists in the making, Patti hopes they will take over her role in the future. That would allow her to refocus on a passion she is itching to pick up again: searching for evidence of sperm whales in the Mediterranean surrounding the Maltese Islands. Her eyes light up as she admits to me, ‘I love outreach, but my personal dream is to spot sperm whales in Malta.’ Researchers know that juvenile and female sperm whales in the Atlantic remain in warm waters while the males migrate to the poles to feed, but movements and social dynamics of pods in the Mediterranean are still unclear.

With an army of environmentalists in the making, Patti hopes they will take over her role in the future.

Looking forward, Patti is working hard to establish networks with other entities and NGOs who share the same vision. EcoMarine Malta already collaborates with the likes of Birdlife Malta and has been involved with beach ‘Clean Up’ projects in the past year. Patti asserts that despite everything, ‘the Maltese public and tourists are some of the most enthusiastic and passionate people we’ve worked with so far. It’s great to see people of all ages and backgrounds, coming together to work on a common goal.’

‘Everyone can contribute different things, and together, it adds up to make a big difference.’ Patti is keen to encourage people to help in whatever way they can. To cooperate with others and not feel overwhelmed or alone in their efforts. ‘It’s not possible to do it alone. We need to work together, holistically, caring about the land, sea, and air, to protect the island’s environment.