Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex, progressive, neurodegenerative condition affecting around 10 million people worldwide. But for every person directly struggling with PD, there is at least one carer, if not an entire family, dedicated to managing the disease. Are we doing enough to support these silent heroes? Cassi Camilleri asks.

‘I’m extremely anxious about her balance. Since the diagnosis, it’s been a constant nightmare because of the risk of falling and getting hurt. In reality, it’s only now that it’s started to become slightly affected,’ says Mildred Atanasio.

Mildred’s mother Rita was diagnosed with PD some years back after her husband passed away. One evening, Rita picked up one of her favourite novels for an evening read and noticed a tremor in her hand.

‘The worst part is when she tells me that all is ok and lovingly attempts to disguise a PD-caused stumble as something less worrying,’ Mildred continues.

‘She does this out of love, we know. She is worried about being a burden on me or my siblings, an idea which cannot be further from the truth. We all love her just the way she is. But this, coupled with my own fear and worry is rather draining… though I think sometimes my mind is worse than the actual symptoms.’

Though her experience is unique in many ways, the feeling of anxiety Mildred goes through is one she shares with many others.

The task of caring for another human being requires time and energy. According to the European Parliament Interest Group on Carers (EPIGC), carers spend an average of 22 hours per week providing for their loved ones. Even when this is done willingly and with love, without the right support network, it can leave carers susceptible to significant strains on their own physical, mental, and emotional health.

The same research by the EPIGC reveals that a third of carers lack sleep and feel depressed. Another third say that they are at a ‘breaking point’; one in five is unable to see anything positive in their life.

Close relatives often take on this important role; however, they often reject the term ‘carer’, seeing their work as a natural extension of the relationship with their affected loved one. ‘I am a daughter first. And the word ‘carer’ does not quite fit in my mental image of things,’ Mildred explains.

However, this has seen many go unrecognised for the service they provide for our community. Often, those who do not register themselves as carers are less likely and less able to access the services available to them.

You are not alone

Working hard to reverse this trend is the Malta Parkinson’s Disease Association (MPDA), with Veronica Clark at the helm as president.

MPDA informs citizens about PD and offers practical help on how to manage symptoms in the home. This includes talks by healthcare professionals so that people with PD and their carers are empowered to better manage their condition.

Peer support meetings foster a discussion about emotional and psychological needs and allow carers to cope with mental health issues they might be facing. Healthcare professionals are employed to further achieve this.

Mildred and her family make use and speak highly of these services. ‘Thanks to the MPDA, we have discovered and happily become part of a strong network of friends,’ Mildred says, a network she describes as very comforting. ‘We also share useful tips among us for day-to-day life which is nice.’

Giving a snapshot of the situation in Malta, Clark is quick to point out the benefits of our national healthcare system, which provides free treatment, accessible to people with Parkinsons in a whole range of disciplines, from neurologists and GPs to physiotherapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists. All this eases pressure on families and carers like Mildred and many others.

Malta also gives access to most PD medications through the government free at the point of use. The same can be said when it comes to any required surgery. This is available ‘without the need to travel,’ Clark specifies, ‘and this is also free, which I will point out is not the case for all European countries.’

An important role the MPDA has is its dissemination of information on how to access support services which may be required outside the family network. The Active Ageing community, Clark tells us, provides services like a carer at home, meals on wheels, home help, and many more. ‘Some aids are free and some are subsidised,’ Clark explains. ‘It is so important that people know they are not alone.’

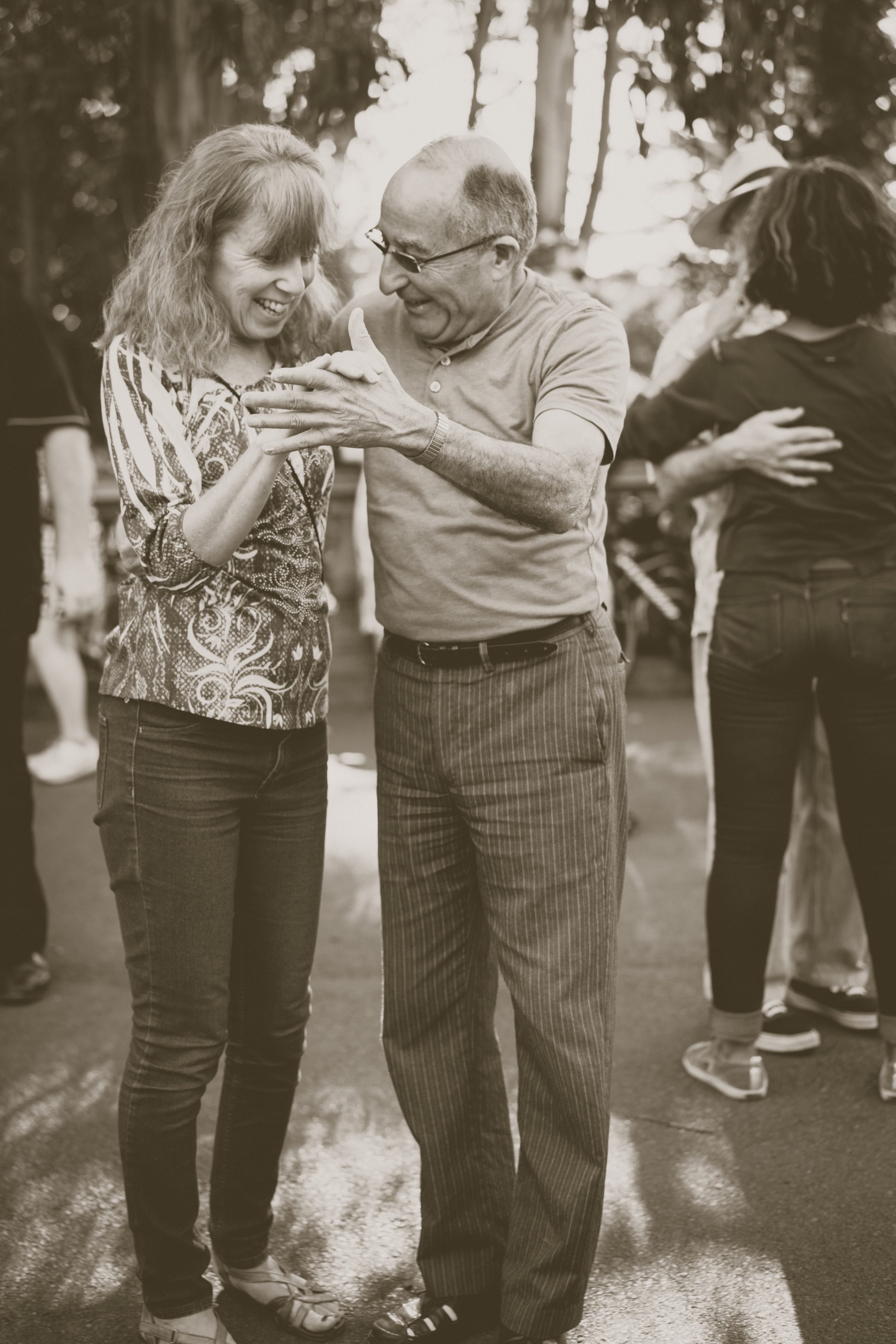

Dancing to better health

Mildred has nothing but wonderful things to say about a special group the MPDA introduced her to — Step Up for Parkinson’s (SUFP).

SUFP are not only dance classes for people with PD and their carers, but a community of people dedicated to uplifting one another.

Dancer Natalie Muschamp founded the organisation around 2016 and hasn’t looked back since.The binding philosophy is to help maintain physical activity of motor movement through dance, all while allowing the person with PD and their carer to bond and enjoy doing something together that isn’t about service.

‘When you have a disease or become a carer, you can lose your identity,’ Muschamp explains. ‘When [our participants] come to the class, they’re just two people and not a sick person and someone taking care of them. We sometimes even separate the couples. We put a lot of emphasis on this. And we encourage them to live their own lives. Some people, even after losing their partners, they continue to come. They regain some of their agency here.’

Of course, there is always room for improvement.

A concern Clark, Mildred, and Muschamp all have is that there are no specialised services tailored specifically for PD — neurologists, PD nurses, therapists, etc.

‘The lack of PD awareness people have at first hand’ is another point Mildred brings up. ‘There are so many misconceptions surrounding the condition,’ she said, ‘which often lead to added difficulties for people with Parkinson’s. To give a few examples, non-motor symptoms, such as hallucinations and impulsivity may easily lead to conflicts within the family unless they are recognised and understood. Slowness and rigidity may force people with Parkinson’s to take longer to cross the road or pay at the counter, leading to undeserved frowns or the tendency of rushing them, often quite unkindly.’

The fact that so many people don’t know what it is like to live with PD creates isolation and damaged relationships across the board. ‘The system needs to address not only the physical part of PD but also the mental, emotional, and social burdens it carries,’ Mildred encourages.

And while both MPDA and SUFP are doing their best to keep making positive changes, there is no escaping the biggest hurdle of all.

‘Co-ordinating regular and timely sessions between health professionals (from both the private and public sector) for people with PD is quite a challenge, due to reduced resources,’ explains Clark. ‘This means leaving people waiting longer or not receiving the regularity of sessions they need to manage their condition.’

The COVID effect

SUFP are also struggling with funding, especially as classes cannot happen in the real world anymore. ‘A lot of our participants struggle with the online thing,’ she explains, ‘and it’s worrying.’

‘For us not going to the gym, it will have an effect on our jean size. But for people suffering with Parkinson’s, it’s much more than that. Some of our participants started declining,’ she reveals sadly.

Ever adapting and creative, Muschamp tried to go around this by repurposing the footage from a cancelled tour with SUFP participants performing in shows all around Malta into a feature length documentary called One Day We Will Dance Again and a TV show called Step Up.

The show will air on ONE TV from January through to June of 2021, providing 15 minutes of daily exercises for the elderly and people with disabilities. ‘Amy, Mildred, Michelle, Roberta, Rowanne, myself, and everyone else — we’re currently in the middle of filming at the moment. Now we just need a good handful of sponsors to come forward — we have adverts to sell!’ she laughs, slapping the table, determined as always.

Knowing full well how infectious her energy is, Muschamp explains where it stems from — community. ‘These people are my people. My family,’ she says. ‘I can’t stop.’

The same goes for Clark. ‘When we see a smile on everyone’s face every month during our [MPDA] meetings, we know that the work we do is meaningful, and this really pushes us to continue to do what we do well,’ she says.

‘It is crucial not to live with PD alone,’ Mildred says, ‘be it the diagnosed person or the one accompanying them, whatever the stage of PD. Get in touch with the MPDA. The committee will be happy to assist them and direct them to any professional healthcare that they may require. And go to the dance classes when they start again. It makes a difference.’

‘We have to remember the bigger picture,’ Muschamp asserts. ‘What if the carer disappears? What if something bad happens to them? What then? The person with PD would need to be institutionalised sooner. The state would need to put even more resources into their care, and the result would be nowhere near as effective, because family is always family. And that does not serve our community. Caring for the carers. That serves our community.’

Resources and links:

Active Ageing services: https://activeageing.gov.mt/Elderly-and-Community%20Care-Services-Information

European Parkinson’s Disease Association: https://www.epda.eu.com/living-well/caring-and-parkinsons/being-the-carer/

Step up for Parkinsons: https://stepupforparkinsons.com/

Malta Parkinson’s Disease Association – www.maltaparkinsons.com