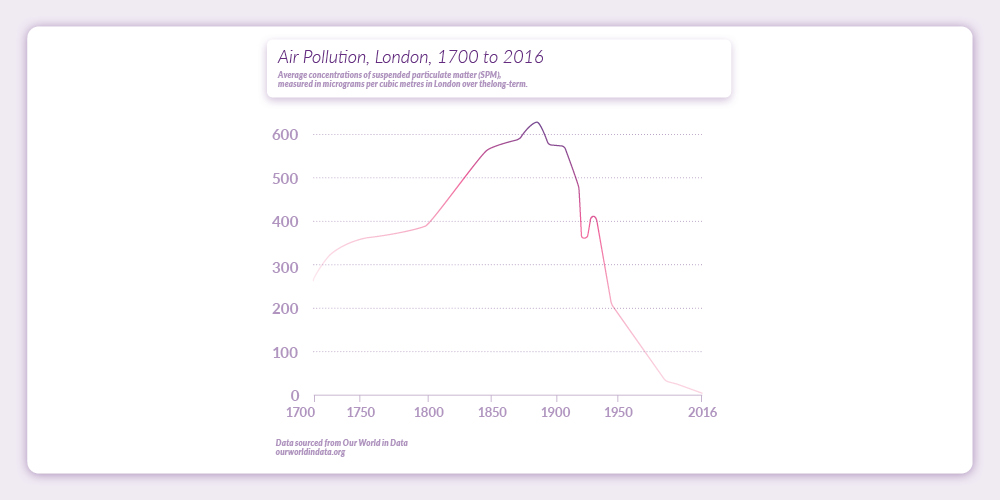

Alternative measures for a country’s success beyond measuring Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are needed. Wellbeing and quality of life do not always follow from economic growth. This realisation goes as far back as the 19th century. Air pollution triggered one of the first societal shifts to improve the environment. The factories of the Industrial Revolution blanketed cities like London in smog, which as early as 1891 led to urgent and severe government action in the form of the Public Health Act. Polluting businesses faced financial penalties unless they cleaned up their act. Air pollution in London has decreased ever since.

This brings us back to how GDP can be replaced as a measure of a country’s success. Quality of life and wellbeing are hard to measure; however, they are important to measure since they also have a tangible impact on the economy. Unhappy and unhealthy people inflate a country’s healthcare costs, and stressed workers produce poorer quality work. A community rendered unrecognisable due to rampant overdevelopment has consequences on people’s sense of place, purpose, and identity.

One of the world’s leading reinsurers, Swiss Re Institute, recently released its Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Index, explaining that 55% of global GDP is dependent on ecosystem and biodiversity services. Malta is listed in the top five countries at risk of ecosystem collapse as a result of a decline in biodiversity services — worrying news for Malta. This index demonstrates that progress is being made to understand the relationship between our environment, our financial success, and our wellbeing in ways which many would not have imagined a few decades ago.

Our economies have been built on the assumption of eternal abundance. As we push up against our natural limits, we are no longer plucking wild fruit, but we are robbing and harming our neighbours, even when this is not immediately obvious. Take deforestation of the Amazon, which directly impacts every person on Earth. Such consequences mean that we must redefine where we consider our rights to begin and end. Short-sightedness and short-term gains lead to the Tragedy of the Commons, where everyone ends up losing when instead everyone could have gained.

The European Union is trying to rebalance things internationally. Its Carbon Border Adjustment tool will penalise unsustainable products entering the EU’s single market from third countries. Such policy instruments are being increasingly refined and adopted, but not quickly enough. To prevent ecosystem collapse and reduce climate change, we must start recognising the true value of our natural resources today, not tomorrow. Malta certainly has the potential, as a small country, to be a leader and set an example for others to follow.