Natural Hazards, Maths, and the Financial World

Does Alcohol kill brain cells?

This myth is HUGE! Urban legend says that drinking kills cells, some even say: ‘three beers kill 10,000 brain cells.’ Thankfully, they are wrong.

In microbiology labs, a 70% alcohol 30% water mix is used to clean surfaces pretty efficiently. It seems our neurons are made of sturdier stuff.

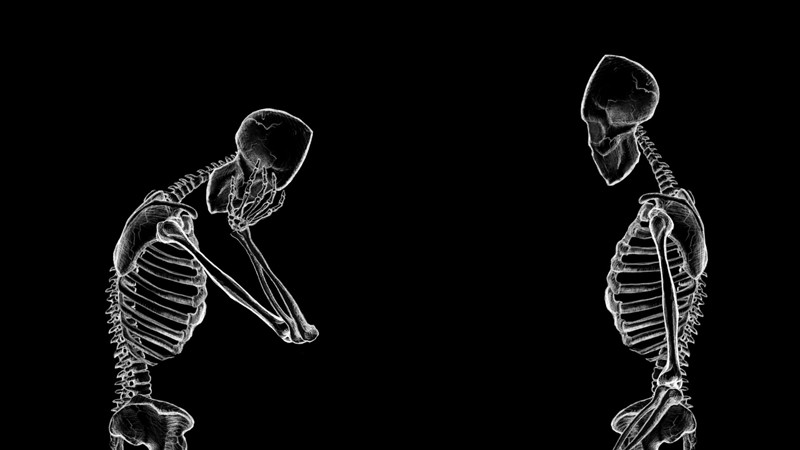

Alcohol does affect brain cells. Everyone knows that and it isn’t pretty. Alcohol can damage dendrites, which are delicate neural extensions that usually convey signals to other neurons. Damaging them prevents information travelling from one neuron to another — a problem. Luckily, the damage isn’t permanent.

Racing into the Future

Way back in 2007, a dedicated group of six people put together a formula-style race car in just six months to compete in a prestigious international competition called FSAE. Since then no other team has participated. Students were always interested to build a racing car but found it too hard to actually carry out — the underlying logistics were simply too much.

Way back in 2007, a dedicated group of six people put together a formula-style race car in just six months to compete in a prestigious international competition called FSAE. Since then no other team has participated. Students were always interested to build a racing car but found it too hard to actually carry out — the underlying logistics were simply too much.

In December 2012, a group of motivated university students founded the University of Malta Racing (UoMR) team. Their mission statement: ‘To encourage and facilitate students of the University of Malta to unite together as a team in the planning, design and construction of a Formula-style race car and to participate in the Formula SAE, or similar competitions.” They were brought together by a love of cars, engines, speed and a competitive spirit.

The 2007 team placed 17th out of 20 teams. The new team has stiff competition and huge challenges to overcome for the upcoming competition in July 2014. Foreign universities compete every year and build a database of knowledge and experience which students use to continue improving their cars. For the UoM to compete eff

The 2007 team placed 17th out of 20 teams. The new team has stiff competition and huge challenges to overcome for the upcoming competition in July 2014. Foreign universities compete every year and build a database of knowledge and experience which students use to continue improving their cars. For the UoM to compete eff

ectively with top-class international universities, there must be a strong framework which supports and encourages students from every faculty, especially the Faculty of Engineering. To overcome this challenge the team extensively researched the parts, materials needed and procedure to build a competitive vehicle. The PR and Finance team of the UoMR also drew up a sponsorship proposal, which was used to attract sponsors and collaborators. Without them the project would not be possible.

The team is currently working on the car’s design. At the same time they are fabricating some parts and structures inside their workshop at University. They are looking for financial or in kind assistance from driving enthusiasts and organisations. •

For more information on UoMR and contact details visit: uomracing.com. The University of Malta’s research trust, RIDT, fully supports the UoM racing team initiative. The trust aims to sustain and grow the UoM’s research activity. Please consider making a contribution at www.ridt.eu

Mapping Cultural Space

Through the Looking Glass

What’s your favourite game? Pacman? Doom? World of Warcraft? Most of us have spent hours immersed in video games, many still do. Prof. Gordon Calleja studies why and how we get so involved in games. Science writer Dr Sedeer El-Showk found out about Calleja’s latest book and game that are gaining worldwide fame.

Celebrating 50 years of the Engineering degree at UoM

By Dr Ing. John C. Betts

Treating stone to save Maltese Culture

Malta has three UNESCO world heritage sites which need constant conservation. Generally, it is better to preserve the original building material than replace it. The conservation method called consolidation can glue deteriorating stone material to the underlying healthy stone maintaining it, but few consolidants have been tested on local Globigerina limestone. Sophie Briffa (supervised by Daniel Vella) tested a new set of consolidants which are stronger than other compounds but affected the colour of the stone. She applied five different conditions on the stone. The first three were novel treatments. They were based on a hybrid silane (tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) and 3-(glycidoxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GPTMS)) but one had nanoparticles, one had modified nanoparticles, and the other lacked them. The fourth was a simple laboratory-prepared TEOS silane. The fifth was untreated limestone samples for comparison.

The treatments successfully penetrated the stone’s surface. Microscopy coupled with other techniques including mercury intrusion porosimetry carried out in Cadiz, Spain, confirmed this infiltration and the stone’s physical qualities: strength, drilling resistance, and so on. Half of the treated stones underwent accelerated weathering. The consolidants with nanoparticles or modified nanoparticles were stronger than the other treatments. They also maintained the original surface colour and improved the stones’ ability to absorb water. On the other hand, they were less resistant to salt crystallisation that can damage the stone making it brittle.

The best consolidant for Maltese stone has not yet been found. Ideally, it should have a good penetration and good weathering properties that preserve the stone’s appearance. It should allow ‘breathability’ and be reversible. Current stone consolidation techniques are irreversible since they permanently introduce new material into the stone. These are only acceptable since consolidation is a last attempt to save the stone before complete replacement.

French writer Victor Hugo summed up the importance of this research when he said, ‘Whatever may be the future of architecture, in whatever manner our young architects may one day solve the question of their art, let us, while waiting for new monuments, preserve the ancient monuments. Let us… inspire the nation with a love for national architecture’.

This research was performed as part of an M.Sc. in Mechanical Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering. The research was funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta).

Titanium: Smoother and shapelier

Electron Beam Melting (EBM) is a state of the art manufacturing process. Using this process product designers will be limited only by their imagination. This technology uses an additive manufacturing approach where parts are built layer by layer — think of ‘3D printing’. It can use exotic metals like titanium alloys, however it does have limitations such as producing a rough surface finish that hampers its functions.

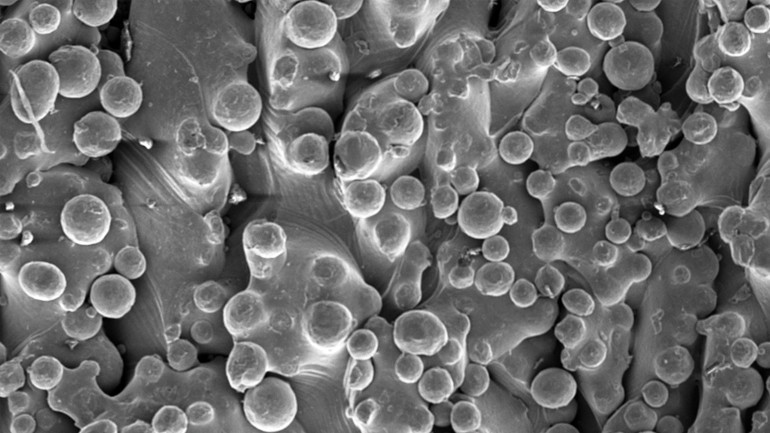

Christian Spiteri (supervised by Dr Arif Rochman) investigated whether the Electric Discharge Machining process can be used to finish parts produced using EBM to give a smooth surface (difference pictured). He treated titanium products with the Electric Discharge Machining process and microscopy showed that the finished surface consists of a set of micro-craters instead of rough grains. By adding the finishing process, more complex geometries could be created. Overall, adding Electric Discharge Machining to EBM had many benefits.

Dr Arif Rochman (University of Malta) said, ‘EBM parts can be used for a wide range of applications such as implants in the medical sector or complex tool inserts, […] which cannot be manufactured using conventional methods. Understanding the synergy between both processes is a must for product designers and process engineers to be able to manufacture high quality EBM products.’

This research was performed as part of a M.Sc. (Res) in Mechanical Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering. This research was partially funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). This Scholarship is part-financed by the European Union – European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II – Cohesion Policy 2007-2013, ‘Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality Of Life’.

Logical chemicals

Chemistry is not usually associated with logic gates, sensors, and circuits. However, a new breed of chemist — the molecular engineer — is adding a bit of chemical spice to them. Given the right tools, his/her hands can synthesize anything, from molecules that assemble into large structures to others that can display information about their environment.

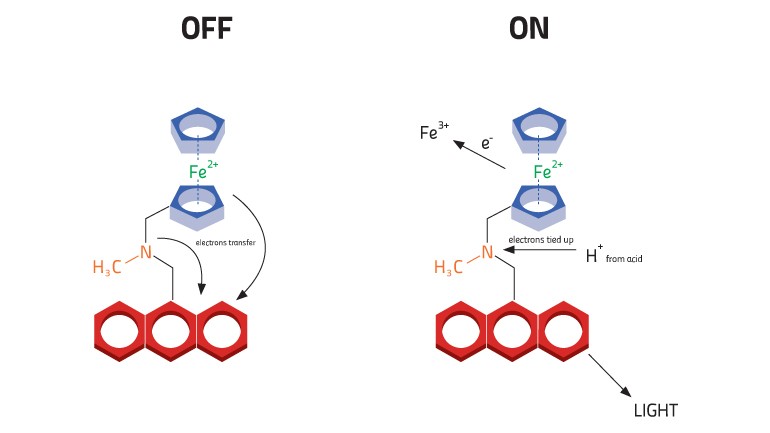

Thomas Farrugia (supervised by Dr David Magri), created a molecule that could be toggled between an ON and OFF state using AND Logic. AND logic means that it needs two chemicals to switch state, adding just one chemical makes no difference. The states are easily recognised by shining UV light on the molecule since only the ON state produces blue light.

In the OFF state, the movement of electrons from two input sites prevents light being released. Stopping the electron transfer enables light release. The blue light shines when specific chemicals bind to the two input sites. The chemicals use up the electrons being transferred, letting the output of the molecule absorb UV light and shine blue light.

The two chemicals added were an acid and an iron (III) source (like what is found in rust). The acid provides hydrogen ions that bind to the nitrogen atom, whilst the iron (III) ions attack the molecule’s iron (II) atom (pictured as Fe). The molecule displays AND logic since it needs both the acid and iron (III) to turn on light emission.

The molecule was synthesised using a one step reaction and tested to determine the strength of the ON and OFF signals. Testing by fluoresence spectroscopy is essential to determine whether it would make a viable sensor, since the technique compares the strength of the ON and OFF state. The molecule will only work well if there is a large difference between the different states, since a machine needs to detect the change.

This molecule can sense the extent of acidity and iron (III) ions in a solution, and convey that information using light, which is easily measured. The molecule’s design could also be integrated into bigger and more complicated molecules so as to carry out other logical and mathematical operations using chemicals. These molecules are a step towards chemical computers.

This research was performed as part of a B.Sc. (Hons) Chemistry with Materials at the Faculty of Science.