Maltese needs to be saved from digital extinction. Dr Albert Gatt, Prof. Gordon Pace, and Mike Rosner write about their work making digital tools for Maltese, interpretting legalese, and making a Maltese-speaking robot

In 2011 an IBM computer called Watson made the headlines after it won an American primetime television quiz called Jeopardy. Over three episodes the computer trounced two human contestants and won a million dollars.

Jeopardy taps into general world knowledge, with contestants being presented with ‘answers’ to which they have to find the right questions. For instance, one of the answers, in the category “Dialling for Dialects”, was: While Maltese borrows many words from Italian, it developed from a dialect of this Semitic language. To which Watson correctly replied with: What is Arabic?

Watson is a good example of state of the art technology that can perform intelligent data mining, sifting through huge databases of information to identify relevant nuggets. It manages to do so very efficiently by exploiting a grid architecture, which is a design that allows it to harness the power of several computer processors working in tandem.

“Maltese has been described as a language in danger of ‘digital extinction’”

This ability alone would not have been enough for it to win an American TV show watched by millions. Watson was so appealing because it used English as an American would.

Consider what it takes for a machine to understand the above query about Maltese. The TV presenter’s voice would cause the air to vibrate and hit the machine’s microphones. If Watson were human, the vibrations would jiggle the hairs inside his ear so that the brain would then chop up the component sounds and analyse them into words extremely rapidly. The problem for a computer is that there is more to language than just sounds and words. A human listener would need to do much more. For example, to figure out that ‘it’ in the question probably refers to ‘Maltese’ (rather than, say, ‘Italian’, which is possible though unlikely in this context). They would also need to figure out that ‘borrow’ is being used differently than when one says borrowing one’s sister’s car. After all, Maltese did not borrow words from Italian on a short-term basis. Clearly the correct interpretation of ‘borrow’ depends on the listener having identified the intended meaning of ‘Maltese’, namely, that it is a language. Watson was equipped with Automatic Speech Recognition technology to do exactly that.

To understand language any listener needs to go beyond mere sound. There are meanings and structures throughout all language levels. A human listener needs to go through them all before saying that they understood the message.

Watson was not just good at understanding; he was pretty good at speaking too. His answers were formulated in a crisp male voice that sounded quite natural, an excellent example of Text-to-Speech synthesis technology. In a fully-fledged human or machine communicating system, going from text to speech requires formulating the text of the message. The process could be thought of as the reverse of understanding, involving much the same levels of linguistic processing.

Machine: say ‘hello’ to Human

The above processes are all classified as Human Language Technology, which can be found in many devices. Human Language Technology can be found everywhere from Siri or Google Now in smart phones to a word processing program that can spell, check grammar, or translate.

Human-machine interaction relies on language to become seamless. The challenge for companies and universities is that, unlike artificial languages (such as those used to program computers or those developed by mathematicians), human languages are riddled with ambiguity. Many words and sentences have multiple meanings and the intended sense often depends on context and on our knowledge of the world. A second problem is that we do not all speak the same language.

Breaking through Maltese

Maltese has been described as a language in danger of ‘digital extinction’. This was the conclusion of a report by META-NET, a European consortium of research centres focusing on language technology. The main problem is a lack of Human Language Technology — resources like word processing programs that can correctly recognise Maltese.

Designing an intelligent computer system with a language ability is far easier in some languages than it is in others. English was the main language in which most of these technologies were developed. Since researchers can combine these ready-made software components instead of developing them themselves, it allows them to focus on larger challenges, such as winning a million dollars on a TV program. In the case of smaller languages, like Maltese, the basic building blocks are still being assembled.

Perhaps the most fundamental building block for any language system is linguistic data in a form that can be processed automatically by a machine. In Human Language Technology, the first step is usually to acquire a corpus, a large repository of text or speech, in the form of books, articles, recordings, or anything else that happens to be available in the correct form. Such repositories are exploited using machine-learning techniques, to help systems grasp how the language is typically used. To return to the Jeopardy example, there are now programs that can resolve pronouns such as ‘it’ to identify their antecedents, the element to which they refer. The program should identify that ‘it’ refers to Maltese.

For the Maltese language, researchers have developed a large text/speech repository, electronic lexicons (language’s inventory of its basic units of meaning), and related tools to analyse the language (available for free). Automatic tools exist to annotate this text with basic grammatical and structural information. These tools require a lot of manual work however, once in place, they allow for the development of sophisticated programs. The rest of this article will analyse some of the on-going research using these basic building blocks.

From Legalese to Pets

Many professions benefit from automating tasks using computers. Lawyers and notaries are the next professionals that might benefit from an ongoing project at the University of Malta. These experts draft contracts on a daily basis. For them, machine support is still largely limited to word processing, spell checking, and email services, with no support for a deeper analysis of the contracts they write and the identification of their potential legal consequences, partly through their interaction with other laws.

Contracts suffer from the same challenges when developing Human Language Technology resources. A saving grace is that they are written in ‘legalese’ that lessens some problems. Technology has advanced enough to allow the development of tools that analyse a text to enable extraction of information about the basic elements of contracts, leaving the professional free to analyse the deeper meaning of these contracts.

Deeper analysis is another big challenge in contract analysis. It is not restricted to just identifying the core ‘meaning’ or message, but needs to account the underlying reasoning behind legal norms. Such reasoning is different from traditional logic, since it talks about how things should be as opposed to how they are. Formal logical reasoning has a long history, but researchers are still trying to identify how one can think precisely about norms which affect definitions. Misunderstood definitions can land a person in jail.

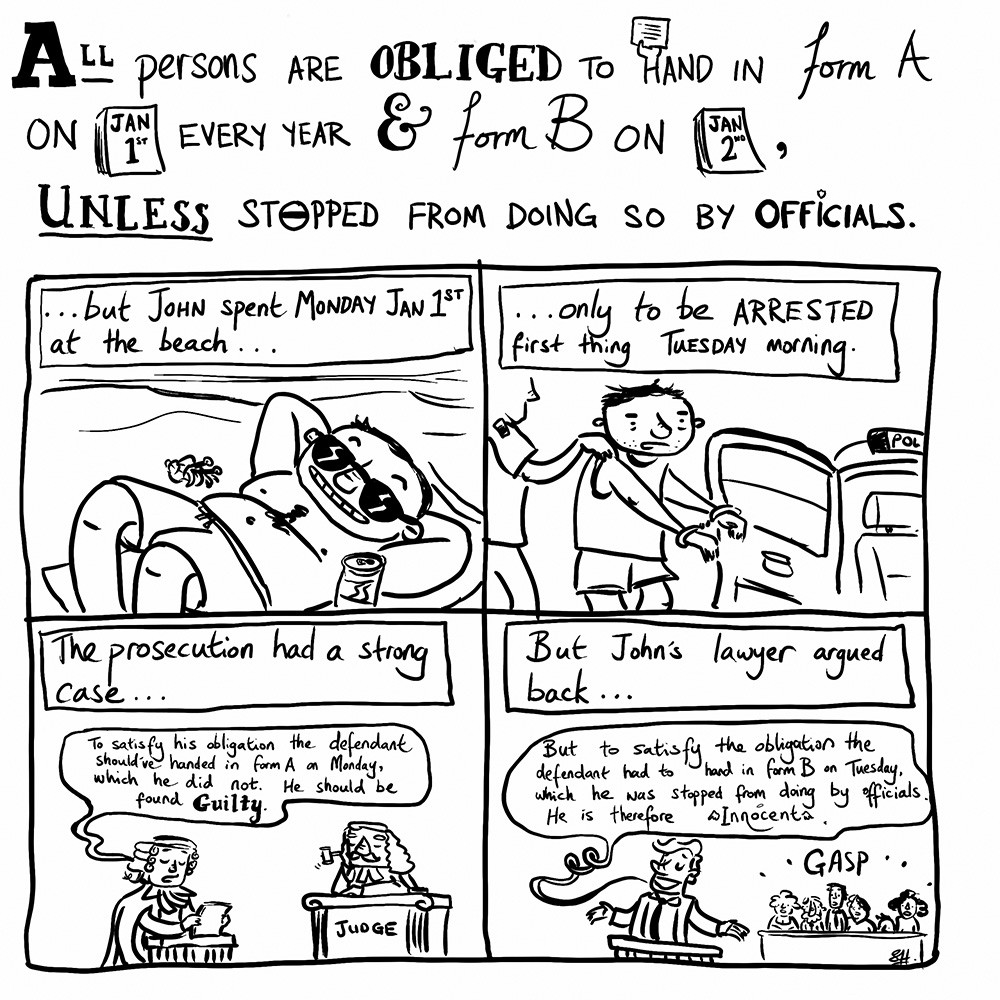

Consider the following problem. What if a country legislates that: ‘Every year, every person must hand in Form A on 1st January, and Form B on 2nd January, unless stopped by officials.’ Exactly at midnight between the 1st and 2nd of January the police arrest John for not having handed in Form A. He is kept under arrest until the following day, when his case is heard in court. The prosecuting lawyer argues that John should be found guilty because, by not handing in Form A on 1st January he has violated the law. The defendant’s lawyer argues that, since John was under arrest throughout the 2nd of January he was being stopped by officials from handing in Form B, absolving him of part of his legal obligation. Hence, he is innocent. Who is right? If we were to analyse the text of the law logically, which version should be adopted? The logical reasoning behind legal documents can be complicated, which is precisely why tools are needed to support lawyers and notaries who draft such texts.

Figuring out legal documents might seem very different to what Watson was coping with. But there is an important link: both involve understanding natural language (normal every day language) for something, be it computer, robot, or software, to do something specific. Analysing contracts is different because the knowledge required involves reasoning. So we are trying to wed recent advances in Human Language Technology with advances in formal logical reasoning.

Contract drafting can be supported in many ways, from a simple cross-referencing facility, enabling an author to identify links between a contract and existing laws, to identifying conflicts within the legal text. Since contracts are written in a natural language, linguistic analysis is vital to properly analyse a text. For example in a rent contract when making a clause about keeping dogs there would need to be a cross-reference to legislation about pet ownership.

We (the authors) are developing tools that integrate with word processors to help lawyers or notaries draft contracts. Results are presented as recommendations rather than automated changes, keeping the lawyer or notary in control.

Robots ’R’ Us

So far we have only discussed how language is analysed and produced. Of course, humans are not simply language-producing engines; a large amount of human communication involves body language. We use gestures to enhance communication — for example, to point to things or mime actions as we speak — and facial expressions to show emotions. Watson may be very clever indeed, but is still a disembodied voice. Imagine taking it home to meet the parents.

“Robby the Robot from the 1956 film Forbidden Planet, refused to obey a human’s orders”

Robotics is forging strong links with Human Language Technology. Robots can provide bodies for disembodied sounds allowing them to communicate in a more human-like manner.

Robots have captured the public imagination since the beginning of science fiction. For example, Robby the Robot from the 1956 film Forbidden Planet, refused to obey a human’s orders, a key plot element. He disobeyed because they conflicted with ‘the three laws of robotics’, as laid down by Isaac Asimov in 1942. These imaginary robots look somewhat human-shaped and are not only anthropomorphic, but they think and even make value judgements.

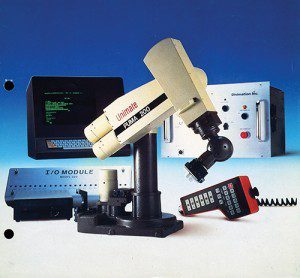

Actual robots tend to be more mundane. Industry uses them to cut costs and improve reliability. For example, the Unimate Puma, which was designed in 1963, is a robotic arm used by General Motors to assemble cars.

The Puma became popular because of its programmable memory, which allowed quick and cheap reconfiguration to handle different tasks. But the basic design was inflexible to unanticipated changes inevitably ending in failure. Current research is closing the gap between Robby and Puma.

Opinions may be divided on the exact nature of robots, but three main qualities define a robot: one, a physical body; two, capable of complex, autonomous actions; and three, able to communicate. Very roughly, advances in robotics push along these three highly intertwined axes.

At the UoM we are working on research that pushes forward all three, though it might take some time before we construct a Robby 2. We are developing languages for communicating with robots that are natural for humans to use, but are not as complex as natural languages like Maltese. Naturalness is a hard notion to pin down. But we can judge that one thing is more or less natural than another. For example, the language of logic is highly unnatural, while using a restricted form of Maltese would be more natural. It could be restricted in its vocabulary and grammar to make it easier for a robot to handle.

Take the language of a Lego EV3 Mindstorms robot and imagine a three-instruction program. The first would be to start its motors, the second to wait until light intensity drops to a specific amount, the third to stop. The reference to light intensity is not a natural way to communicate information to a robot. When we talk to people we are not expected to understand how the way we put our spoken words relates to their hardware. The program is telling the robot to: move forward until you reach a black line. Unlike the literal translation, this more natural version employs concepts at a much higher level and hence is accessible to anybody with a grasp of English.

Take the language of a Lego EV3 Mindstorms robot and imagine a three-instruction program. The first would be to start its motors, the second to wait until light intensity drops to a specific amount, the third to stop. The reference to light intensity is not a natural way to communicate information to a robot. When we talk to people we are not expected to understand how the way we put our spoken words relates to their hardware. The program is telling the robot to: move forward until you reach a black line. Unlike the literal translation, this more natural version employs concepts at a much higher level and hence is accessible to anybody with a grasp of English.

The first step is to develop programs that translate commands spoken by people into underlying machine instructions understood by robots. These commands will typically describe complex physical actions that are carried out in physical space. Robots need to be equipped with the linguistic abilities necessary to understand these commands, so that we can tell a robot something like ‘when you reach the door near the table go through it’.

To develop a robot that can understand this command a team with a diverse skillset is needed. Language, translation, the robot’s design and movement, ability to move and AI (Artificial Intelligence) all need to work together. The robot must turn language into action. It must know that it needs to go through the door, not through the table, and that it should first perceive the door and then move through it. A problem arises if the door is closed so the robot must know what a door is used for, how to open and close it, and what the consequences are. For this it needs reasoning ability and the necessary physical coordination. Opening a door might seem simple, but it involves complex hand movements and just the right grip. Robots need to achieve complex behaviours and movements to operate in the real world.

The point is that a robot that can understand these commands is very different to the Puma. To build it we must first solve the problem of understanding the part of natural language dealing with spatially located tasks. In so doing the robot becomes a little bit more human.

A longer-term aim is to engage the robot in two-way conversation and have it report on its observations — as Princess Leia did with RT-D2 in Star Wars, if RT-D2 could speak.

Language for the World

Human Language Technologies are already changing the world. From automated announcements at airports, to smartphones that can speak back to us, to automatic translation on demand. Human Language Technologies help humans interact with machines and with each other. But the revolution has only just begun. We are beginning to see programs that link language with reasoning, and as robots become mentally and physically more adept the need to talk with them as partners will become ever more urgent. There are still a lot of hurdles to overcome.

To make the right advances, language experts will need to work with engineers and ICT experts. Then having won another million bucks on a TV show, a future Watson will get up, shake the host’s hand, and maybe give a cheeky wink to the camera.