Dr Karsten Xuereb tells us about the role of culture in the Arab world

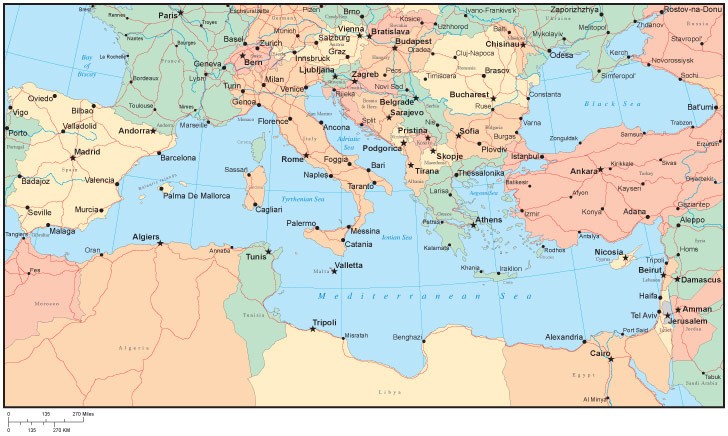

European cultural institutes are spread throughout the Southern Mediterranean. Each institute takes on a different political, social, and economic role depending on the country’s culture. Local communities have expectations from cultural projects that influence the challenges within each country and their European partner. Projects may aim at developing partnerships, yet the starting points may vary and colonial elements are still highly influential. To learn more about the influence of European cultural institutes in the Southern Mediterranean, I carried out interviews with artists and cultural operators in Algeria, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, and Malta. Through them I gained insight into the realities experienced by people active in their own territory, while using these experiences to reflect on the wider Mediterranean. The people contacted are engaged on both local and international levels, which allowed for a fruitful exchange of ideas and experiences. I contacted colleagues and friends from the Association BJCEM (Biennial of Young Artists of Europe and the Mediterranean), established in 1985 in Barcelona and one of the veteran artistic initiatives in the region, represented locally by the literary association Inizjamed. BJCEM opened up contacts who are active cultural participants in each location, as well as in Europe and the Mediterranean.

Different Mediterranean territories offer their own blend of cultural expression and cooperation. Their particular characteristics need to be respected. However, my research aims at extracting indicators of common challenges and opportunities faced by people within these different territories. The goal is to provide reflections and recommendations which cater for local realities within the Mediterranean. As a result, the outcome is to propose a set of common actions. As argued by the UCLG (United Cities and Local Government) in Agenda 21, working together with a greater understanding of each other would benefit the different Mediterranean communities. This is preferable to maintaining today’s situation where each city or local authority operates separately or with limited cooperation.

The interviews also show that the term ‘the Arab world’ is a gross oversimplification of the complex existing realities. Nevertheless, common trends do exist and are used as reference points in the accompanying analysis. In writing about common cultural challenges faced by the Arab world in the Mediterranean context, the reflections offered by Ahmed Moatassime are of particular assistance. He notes that identity is mainly related to language, self-perceptionand representation. These are important focal points for any research dealing with cultural relations in the Mediterranean. Moatassime’s aspects strongly featured in the interviews, together with the interaction between contemporary and traditional interpretations of identity. In ways which recall observations by Toynbee as well as Franco Cassano on power struggles in cultural relations, Moatassime notes there are many geopolitical and geosocial elements at play.  He identifies two opposing lines that are of critical importance in this analysis. The first is the ‘cultural resistance’ that favours the ‘specific’, in the expression and study of personal plus collective identity, in other words, what individuals and communities express and experience in an area. The second is the wider, more encompassing perspective which is connected to the overarching geopolitical realities. For this research, the framework of geopolitical realities are provided by cultural relations within the Mediterranean.

He identifies two opposing lines that are of critical importance in this analysis. The first is the ‘cultural resistance’ that favours the ‘specific’, in the expression and study of personal plus collective identity, in other words, what individuals and communities express and experience in an area. The second is the wider, more encompassing perspective which is connected to the overarching geopolitical realities. For this research, the framework of geopolitical realities are provided by cultural relations within the Mediterranean.

Moatassime highlights two other important elements which shape Arab cultural expression in relation to Europe and the Mediterranean, namely:

I. the Mediterranean North–South divide is represented by who dominates whom; and II. the influence of globalisation, European influence, and culture. He notes that Francophony, Europeanism, and globalisation (coupled to the US, China, and Brazil) can be described as ‘extra-Mediterranean’, but over time, they have enmeshed themselves within the Mediterranean fabric. Moatassime’s analysis is also useful in my research by distinguishing between different groups of Arab people from the Southern Mediterranean by identifying them as:

I. Europhiles (or those who put foreign cultures before their own);

II. local culture supporters;

III. those at ease with both cultures.

The social and political upheaval in the Southern Mediterranean has changed the context of culture in these states. As pointed out by Marc Lynch, these recent developments have gone hand-in-hand with cultural, artistic, and political expression. At the moment of protest, these fused into powerful tools for change. As Lynch notes with good foresight, the emergence of a transnational public sphere was driven by domestic repression and political entrepreneurs. They took advantage of new media opportunities to invoke a shared identity.

“the term ‘the Arab world’ is a gross oversimplification of the complex existing realities”

The study of cultural policy allows engagement with various elements of human expression. It encourages the interested individual to structure diverse outcomes in ways which may lead to recommendations and action. All across the Southern Mediterranean there are concerns with language and ethnic belonging to identify groups, the flow of migrants and the mix of cultures, the struggle to make projects happen in spite of limited resources, and establishing structures for communities, like schools and centres. In each territory the wants are different but urgent. For change to take place, a thorough analysis of the situation can drive a plan for sustainable action based on solid political will, vision and a concern with the human dimension. •

Karsten Xuereb was recently awarded a Ph.D cum laude in cultural policy (Universitat Rovira i Virgili Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain). Dr Xuereb was tutored by Professor Enric Olivé Serret (UNESCO Chair on intercultural dialogue in the Mediterranean) and assessed by Professor Franco Cassano, University of Bari. Dr Xuereb is Project Coordinator for the Valletta 2018 Foundation. The research document may be accessed here:

http://hdl.handle.net/10803/97209

Find out more:

BOUQUEREL, Fanny; EL HUSSEINY, Basma (2009). Towards A Strategy for Culture in the Mediterranean Region, EC Preparatory document: Needs and opportunities assessment report in the field of cultural policy and dialogue in the Mediterranean Region,

http://bit.ly/ThinkV18a.

MOATASSIME, Ahmed (2006). Langages du Maghreb face aux enjeux culturels euro-méditerranéens, L’Harmattan, Paris.

LYNCH, Marc (2012). The Arab Uprising, Public Affairs, New York.

Comments are closed for this article!