Eyes front!

How often do your date’s eyes glance down at your chest? Which products do people notice in a supermarket? How long does it take you to read a billboard?

Eye trackers are helping researchers around the world answer questions like these. From analysing user experience to developing a new generation of video games, this technology offers a novel way of interacting with machines. People with disabilities, for example, can use them to control computers. A team at the Department of Systems and Control Engineering (University of Malta) is using a research-grade eye-gaze tracker, worth around €40,000, to test technologies they are planning to commercialise soon.

Continue readingSTEM ambassadors thrashing stereotypes

Over the last four decades, STEM industries have risen to great heights. Scientific, technological, engineering, and mathematical minds have been called to rally. And the demand continues. How can you contribute?

Few would dispute that technological and scientific advancements dominate the 21st century. Adverts provide ample proof. From tablets to smartphones, to robot home appliances and driverless cars, our world is changing fast. As a result, we are now living in a global knowledge-based economy where information can be considered as the highest form of currency. This reality comes with both benefits and challenges.

Statistics from 2013’s European Company Survey show that 39% of European Union-based firms had difficulty recruiting staff with STEM skills. Malta is no exception. Another report in 2018 showed that people with STEM careers are still in short supply locally, especially in the fields of healthcare, ICT, engineering, and research. So, while the jobs are available, there aren’t enough people taking up STEM careers, and this is holding Malta back.

There are many reasons for this trend. For one, Malta has a low number of tertiary level graduates; the third lowest in the EU. An array of harmful stereotypes can also shoulder some blame. The ‘fact’ that people in math, science, and technology ‘don’t have a social life’ is unhelpful. The ‘nerd’ image is still prevalent, especially among the younger generations that are still in primary and secondary school. Then there is the ‘maleness’ associated with STEM jobs and industries. According to Eurostat statistics, in 2017, from 18 million scientists and engineers in the EU, 59% were men and 41% women.

Still, this is far from the whole picture.

Employers have reported instances where, despite having enough graduates to fill roles, applicants did not possess the right non-technical skills for the job. This was especially true for abilities such as communication, creative thinking, and conflict resolution.

Many were unprepared to work in a team, to learn on the job, and to problem solve creatively. This is a real concern, especially for the country’s future. At the rate with which markets are evolving, a decade from now young people will be applying for jobs that do not exist today, and the country needs to prepare students for these roles. And it has to start now.

The Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) is trying to do this through an Erasmus+ project called RAISE. They are launching an Ambassador Programme to empower young students to take up the STEM mantle. STEM Career Cafés are going to be popping up in schools all over Malta, alongside a Career Day at Esplora aimed to inform and inspire. This is where you come in.

They want undergraduates from the University of Malta and MCAST to work with Esplora by sharing your experiences in STEM and telling your stories to encourage those who may be considering a STEM career. STEM Ambassadors will gain important public engagement skills while making research and science careers more accessible.

STEM is crucial in our contemporary world; our economies depend on it. It has completely changed the way we live and opened up new prospects for a future we never imagined. For those who have already made up their mind to be a part of it, there is now the opportunity to empower others and guide them in finding their own path.

Note: To become a STEM Ambassador, email programmes@esplora.org.mt or call 2360 2218.

The MCST, the University of Malta, and the Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology have embarked on a national campaign to promote STEM Engagement. Its first activity was a National STEM Engagement Conference.

Research to business plan: A metamorphosis

Author: Michelle Cortis

In recent years, there has been a shift in the relationship between research and commercial industries. Commercial viability almost always comes into question for ongoing research. Commercialisation can be a boon. When a research project has demonstrated its potential to become a viable business, funding opportunities increase, meaning the research can be turned into a product or service that people can use.

In 2018, as part of a Masters in Knowledge-Based Entrepreneurship, I analysed the commercial potential of an ongoing University of Malta project. I conducted an in-depth market feasibility study on Prof. Ing Joseph Cilia’s Smart Micro Combined Heat and Power System, a device that can be fitted into homes and offices to deliver heat as a by-product of electricity, reducing energy costs. Many EU countries are setting up incentives to make these systems more feasible and attractive to consumers.

For my dissertation, I developed a business plan for the research team. An engineer myself, and having earned a Masters by Research back in 2014, this was different to anything I had done before. My supervisors, Prof. Russell Smith and Dr Ing. Nicholas Sammut, helped me find the right balance between utilising my technical knowledge whilst also analysing the product’s commercial potential. Even my language changed through the process; I began to speak of ‘euros per day’ rather than ‘kilowatt hours’. I learnt to differentiate between technological features and what real benefits future users would gain.

Being presented with a physical product, initially one may assume that it is to be sold to customers, or protected through a patent and licensed to the private sector. However, my market analysis revealed new target audiences that had not been thought of before. Selling the device was not the only way to exploit the project’s commercial potential. What if we leased the product instead of selling it? Should we continue developing the product or is it already innovative enough? What if we developed a spin-out—would it be too expensive or is it worth the investment?

By analysing a project through a commercial lens, all these questions arise, pointing out potential ways to make a good project great. But what makes a good business plan great is when all these questions are answered.

The Project ‘A Smart Micro Combined Heat and Power System’ is financed by the Malta Council for Science & Technology, for and on behalf of the Foundation for Science and Technology through the FUSION: R&I Technology and Development Programme.

Are you carrying out research at the University of Malta which you think may have commercial potential? If so, contact the Knowledge Transfer Office on knowledgetransfer@um.edu.mt

Taking solar to sea

In a world first, a small team of engineers at the University of Malta is attempting to prove that harnessing solar power in the open sea is theoretically possible and cost-effective. Laura Bonnici speaks to Prof. Luciano Mulѐ Stagno to learn more about the ground-breaking Solaqua 2.1 project.

Renewable energy is in the spotlight. In Malta—an island that is said to enjoy an average of 300 days of sunshine per year—solar power has become mainstream, enabling the country to reach its goal of using 10% renewable energy by 2020.

But any advantage Malta has in terms of abundant sunshine, it loses through its lack of another vital resource: space. Measuring just 316 km², Malta’s limited surface area means that, beyond the existing photovoltaic (PV) panels installed on rooftops or disused quarries, any land left for larger PV installations is rare and expensive.

Prof. Luciano Mulѐ Stagno at the University of Malta believes the answer to this problem lies not on land, but at sea. Malta being surrounded by water, he has proposed that installing solar panels in open water, in offshore floating PV farms, could be as cost-effective and reliable as those on land—an idea that has never progressed beyond the theoretical stage anywhere in the world.

‘There are many PV projects happening on fresh water everywhere, from China and the UK to France and USA. But none of them are working on open sea,’ explains Mulѐ Stagno. ‘Their PV farms are installed in more sheltered, land-locked waters such as irrigation ponds or lakes, believing that PV farms cannot survive sea conditions. The Solaqua project aims to prove that they can survive, and do so at a comparable cost to land-based PV farms.’

When funding was secured from MCST in 2012, the previous Solaqua 1.0 project set about achieving these ambitious aims. Testing various prototypes out at sea, it confirmed that large, floating platforms were viable, cheap to construct, and could produce more power than similar systems on land.

The sea proved beneficial for many reasons. ‘The offshore panels produced around 3% more energy than similar land-based modules simply by being at sea, possibly due to the cooler temperatures at sea and a less dusty environment.’

The success of the first project inspired a second. With this one, the modular raft was designed and tested. ‘Solaqua 2.0 was financed by Takeoff [The University of Malta’s business incubator] in July 2017, with a preliminary design for the platform almost completed. Now discussions are underway about possible patents for the design,’ Mulѐ Stagno elaborates. ‘The ultimate aim is to launch a large farm in Maltese territorial water which, if it meets

the cost and power output targets, will be followed by other systems worldwide.’

The Professor and his team (marine structural engineer Dr Federica Strati, systems engineer Ing. Ryan Bugeja, and engineer Martin Grech) are now starting the next phase of the Solaqua project. Before the team builds and launches a full-scale system, they have to conduct a series of rigorous wave tank tests. Using a scale model while mimicking the worst possible sea conditions that the system may encounter, the team will be able to refine the design and optimise power output by testing the effect of water motion, cooling, or even different types of panels.

‘Through Solaqua 2.1, we hope to reassure investors that the system is viable. Once completed, we will be ready to launch a full-scale system that could be used not only by islands such as Malta, but also in coastal cities around the world which have insufficient land available for PV systems.’

Investors are being invited to join this project to push for global commercialisation. To reach this stage, several local entities supported the project. The Regulator for Energy and Water Services, with the help of the RIDT (the University of Malta’s Research Trust), invested €100,000 to cover the cost of constructing the scale model, as well as testing, equipment, transport, and engineers. And now that the project is commanding international interest, potential investors are being sought for the half a million euros needed to achieve a full-scale floating solar farm in Maltese waters.

‘This is a homegrown project, in which Malta could be an example to the world,’ explains Mulѐ Stagno. ‘We have already placed Malta at the cutting edge of this research area by being the first to test small systems in the open sea. Now we need to find an investor willing to take the plunge and help us create the world’s first full-scale floating solar farm. With Solaqua, Malta could be at the forefront of a ground-breaking new global industry—one which has the potential to change the way solar power is collected and used the world over.’

Safe haven?

Some refer to the Venice Biennale as the pinnacle of the international art world. Last year, feathers were flurried by the Maltese delegation and their representation of Maltese identity. This year, the works question a specific part of the Maltese narrative.

‘We are working around the theme of MALETH,’ says Dr Trevor Borg, artist, curator, and University of Malta lecturer. Maleth refers to the ancient word for Malta. ‘It is also called HAVEN and SAFE PORT.’ These were all terms used in reference to Malta over the centuries. But is our island really that? This is the question being tackled by Borg and his colleagues.

Immigration has been a critical issue in recent years, creating an inflammatory divide in Malta. Borg is using the first immigrants, the animals that travelled to Malta during the ice age, to make his point. ‘They travelled here because of the heat our island provided and the food that came with it. But as the ice in the North started to melt, sea level rose and they were unable to return.’

What is the relation between an (apparent) safe haven and a heterotopia? Here, heterotopia refers to Michel Foucault‘s notion of the ‘other place’. Heterotopias are described as ‘worlds within worlds’, connecting different places. They are places that constitute multiple layers of meaning, that accumulate time, that can be both real and unreal.

To represent this visually, Borg is going to create an archaeological find with hundreds of objects from history. Animal remains will feature, as will unusual artefacts and other strange finds. Borg was inspired by Ghar Dalam and used it as a starting point, but this work is not about history. ‘My work begins at the cave. But I will then leave the cave behind and delve into a distant world that never was! The work responds to fabricated histories, museological conventions, historical interpretations, and hypothetical authenticity. It is based on pseudo-archaeological objects and imaginary narratives,’ he explains.

Collaborating on this work, bringing the artefacts to life is Dr Ing. Emmanuel Francalanza (Faculty of Engineering). The process began at the National History museum in Mdina. ‘Together we selected and scanned a number of animal bones from their archives,’ Francalanza says. This included femurs, teeth, and skulls among others. ‘I then supported Trevor in reconstructing the 3D model and preparing it for printing.’

For Francalanza, this was a chance to apply engineering technologies in new ways, to allow artists to express themselves. But not just. ‘At the same time, this opportunity provides us engineers and scientists with an avenue to explore concepts and even utilise thinking patterns which are not traditionally associated with our disciplines. It helps us be more creative and open to innovative practices.’

Working together, Borg and Francalanza are blurring the lines between what is real and what is fake. By recreating the original artefacts in such a way that a viewer cannot determine whether what is being seen is authentic, the project is poignant commentary for the post-truth era we are living in.

Pushing for Malta’s industrial renaissance

With all the cranes strewn across the Maltese landscape, it appears that the construction industry is one of Malta’s primary economic drivers. But there are other, less polluting ways of generating income. Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi discusses MEMENTO, the high-performance electronics project that could pave the way for a much-needed cultural shift in manufacturing.

Continue readingUp, up and away!

How do aerospace research engineers test new cockpit technologies without having to actually fly a plane Answer: flight simulators. These machines give pilots and engineers a safe, controlled environment in which to practise their flying and test out new technologies. In 2016 the team at the Institute of Aerospace Technologies at the University of Malta (IAT) started work on its first-ever flight simulator—SARAH (Simulator for Avionics Research and Aircraft HMI). Its outer shell was already available, having been constructed a few years back by Prof Carmel Pulé. From there, the team built the flight deck hardware and simulation software, and installed all the wiring as well as side sticks, pedals, a Flight Control Unit (FCU) and a central pedestal. The team constructing the simulator faced many hurdles. The biggest challenge was coordinating amongst everyone involved in the build: students, suppliers, and academic and technical staff. Careful planning was crucial.

The result is a simulator representative of an Airbus aircraft. However, it can also be easily reconfigured to simulate other aircraft, making it ideal for research purposes and experimentation. The Instructor Operating Station (IOS) also makes it possible to select a departure airport and change weather conditions.

One of the first uses of SARAH was to conduct research on technology that enables pilots to interact with cockpit automation using touchscreen gestures and voice commands. This research was conducted as part of the TOUCH-FLIGHT 2 research and innovation project (read more about this in Issue 19).

Going beyond the original aim of SARAH being used for research purposes, the IAT is also using the technology to educate graduates and young children in the hope of sparking an interest in the field. Earlier this year, a group of secondary school students flew their own virtual planes under the guidance of a professional airline pilot.

Looking ahead, the IAT plans to incorporate more state-of-the-art equipment into SARAH to increase its capabilities and make the user experience even more realistic. There are also plans to build other simulators—including a full-motion flight simulator and an Air Traffic Control simulator—and to connect them together to simulate more complex scenarios involving pilots and air traffic controllers; a scenario that would more closely resemble the experience of a real airport.Project TOUCH-FLIGHT 2 was financed by the Malta Council for Science & Technology, for and on behalf of the Foundation for Science and Technology, through the FUSION: R&I Technology Development Programme.

Author: Abigail Galea

Blood in the brain

Artificial intelligence (AI) has now made its way into the medical world. But it’s not as scary as it sounds. Most forms of AI are simply programs which have been developed to carry out very specific tasks–and they do them very well.

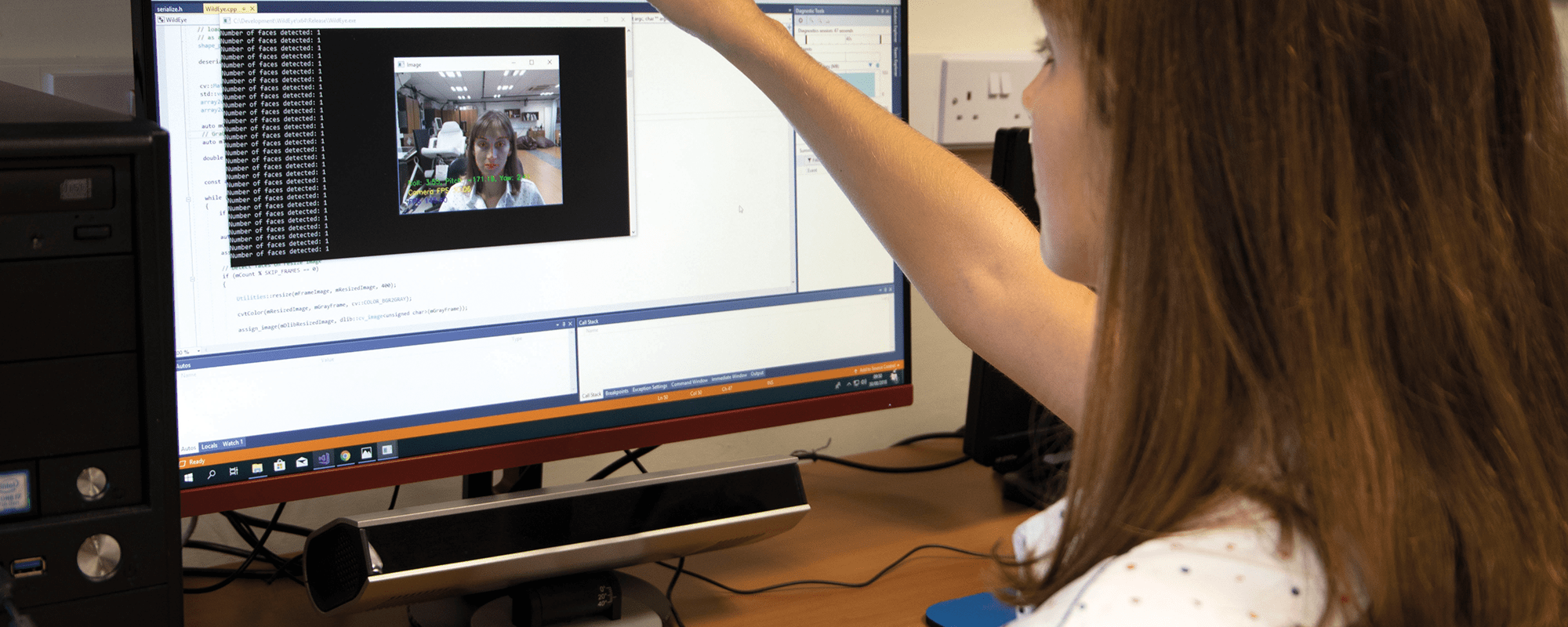

As part of my final-year project, I used AI to develop a program that can diagnose different types of brain haemorrhages. Brain haemorrhages are life-or-death situations where blood vessels in the brain burst and bleed into surrounding tissues, killing brain cells. Speed is key in preventing long-term brain damage, but treatment options depend on the size and location of the haemorrhage. This is when computerised tomography, or CT scans, come in.

Using X-rays, CT scans can image the brain in seconds. Last year, John Napier (another final-year project student) created an AI system to detect brain haemorrhages from CT scans. Building on this, I (under the supervision of Prof. Ing. Carl James Debono, Dr Paul Bezzina, and Dr Francis Zarb) developed a system to take the output from Napier’s system and further analyse the intensity, shape, and texture of haemorrhages to identify them as one of three types.

The AI was trained on 24 pre-classified CT scans. By presenting the scan image to the artificial neural network along with the answer, the system can take on the information and learn. This process trains it to become familiar with the types of haemorrhage. Two different structures of artificial neural network were used with 220 variants each–resulting in 440 variants being used to train and test the model.

Then it was time to test this system. Six scans were given as unknowns and the network successfully classified over 88% of the haemorrhages using only three of the 440 variants.

The purpose of this system is to verify radiologists’ diagnoses. However, we hope to develop it to diagnose haemorrhages, which would help treat patients faster. The system can be adapted to other illnesses–CT scans are commonly used to image the abdomen and chest. The applications, and life-saving potential, are endless.

This research was carried out as part of a Bachelor’s degree in Computer Engineering at the Faculty of ICT, University of Malta.

Author: Kirsty Sant

Women in science, do it with art

STEM subjects tend to intimidate, seeming inaccessible to the untrained eye. Dr Vanessa Camilleri, Dr Marie Briguglio, and Prof. Cristiana Sebu speak to Becky Catrin Jones about how they are challenging preconceptions by combining science and art at Science in the City, Malta’s national science festival.

It’s 2018. We live in a world where saliva samples sent out from the comfort of our own homes return to us with a sprawling outline of our ancestry and where some of the biggest social media influencers are robots. Despite this progress, utter the word ‘scientist’ and the outdated image of men in white lab coats still abound.

When advances in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) direct almost every aspect of life, why is it that so many still switch off the minute we mention science?

Researchers haven’t always had the best PR. In films and TV, science is often portrayed as a foreign language, gibberish to most. Real life is not always that much better, with some researchers needing to carry a jargon-busting dictionary around to translate what they study. To improve its reputation, we need a more creative approach that can break these stereotypes and bring science to the masses in a way that doesn’t send people running for the hills.

Science in the City (SitC), Malta’s science and arts festival, is the perfect opportunity for researchers at the University of Malta (UM) to bring their research to citizens in a way that doesn’t need subtitles.

Professor Cristiana Sebu (Department of Mathematics, UM) joined UM only three years ago, but has already made a firm mark. With a background in Applied Mathematics, she moved to the university as an Associate Professor, setting up a new course stream for undergraduate students in Biomathematics. Sebu’s interests lie in the practical applications of mathematics, particularly in biology, and in exploring how mathematics underpins essentially everything in life. ‘The links between mathematics and biology are strong,’ Sebu asserts. ‘We need to be able to make predictions and apply mathematical modelling to understand complex and intertwined biological systems such as signalling pathways in the body or ecosystems in the environment.’

That said, Sebu is still very aware that her love for mathematics is not often shared by the wider world. The word ‘mathematics’, however applied it might be, still strikes fear into the hearts of many. In an effort to counter this reaction and replace it with a more positive one, Sebu is joining the myriad of researchers at SitC and adding music to the mix.

‘Maths provides the building blocks and the structure of music,’ says Sebu. ‘Debussy, Mozart, Beethoven, and so many more used a mathematical pattern known as the Fibonacci Series in their scores.’ The Fibonacci sequence is an infinite pattern of numbers where the next number is the sum of the two previous ones, going from 1, to 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, where (1+1) = 2, (1+2) = 3, and so on. This sequence is closely related to what’s known as the Golden Ratio, an infinite number which can be found in so many examples throughout nature, from the composition of bee colonies to the shape of seashells and the patterns in sunflower seeds.

Debussy, Mozart, Beethoven, and so many more used a mathematical pattern known as the Fibonacci Series in their scores.

To highlight this elegance, Sebu has teamed up with jazz composer Diccon Cooper. The performance, entitled ‘Jazzing the Golden Ratio’, will feature presentations of the Golden Ratio in art, the environment, and the human body, accompanied by Fibonacci-inspired jazz music specially commissioned for the festival. Sebu herself will also be there, sharing her thoughts about the significance of this pattern in the world around us. ‘People see arts and science at odds, but the two are very much embedded in each other,’ Sebu states. ‘Hopefully we’ll be able to demonstrate the beauty of mathematics at Science in the City this year.’

The significance of this connection between arts and science is a notion shared by Dr Vanessa Camilleri (Faculty of ICT, UM). After working on a project combining Artificial Intelligence (AI) with behavioural studies at Coventry University, Camilleri found a niche research environment using immersive technology and design to influence our decisions and behaviours. Returning to the UM, she worked on a Virtual Reality (VR) headset allowing teachers to experience what it might be like for a child with autism in a classroom.

‘Unless you experience something, it’s very difficult to reach a deep level of empathy,’ Camilleri said of the idea behind the project. ‘We wanted to give [teachers] the opportunity to build new memories through VR, and help them understand the needs of the child in greater detail.’

For SitC this year, Camilleri is taking a different approach. The VR headsets are having the night off, and attendees will need nothing but their smartphones to see science brought to life in artistic form. Using Alternative Reality (AR) methods, she’s collaborating with artists Matthew Attard and Matthew Galea to bring a fourth Triton to the fountain for one night only through a project funded by Valletta 2018. By downloading the smartphone app, attendees will see the new fountain brought to life through their phones. In the build-up to the festival, the artists are using eye-motion tracking and heat mapping sensors on volunteers to see which bits of the current statue draw their attention. This is then translated into the final depiction, making the fourth Triton as eye-catching as the current three.

Lecturer Dr Marie Briguglio (Faculty of Economics, Management & Accountancy, UM) is also hoping to use art to bring her subject to life, albeit in a more sober manner. As a behavioural economist, Briguglio’s focus is on a population’s impact on environment and how we can police this. In particular, at SitC, she wishes to convey the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’—the notion that free or common assets such as public space or air are likely to be exploited by the masses due to sense of entitlement combined with lack of responsibility.

To do this, Briguglio recruited the expertise of Steve Bonello, a cartoonist with a political bent. ‘Working out how best to design environmental regulation underpins much of the research I am involved in. But it’s also very evident in many of the cartoons Steve draws,’ says Briguglio. ‘I soon realized that there was enough material to write a book.’ And so they did, combining the work of faculty with cartoons to produce the comic The Art of Polluting.

Home truths about how we personally damage the world we live in might not make for easy reading, but Briguglio hopes the fusion between arts and science will make this message easier to swallow. ‘It is intended to bring to light research on environmental pressures, status, and responses in a manner that is accessible and also fun.’ The book itself will be displayed as part of a larger instalment titled No Man’s Land, which will include a live action play, more detailed research, and even a free tree-planting stall.

Putting research on the main stage is no new concept to any of these three, and this year’s SitC is certainly not their first venture into science communication. The projects they’ve put forward have all stemmed from previous public engagement ideas. Camilleri worked with the same artists on an AR feature about Greek Mythology, and she regularly translates her research for mass media. A science communication event, Go For Research, which was spearheaded by the Faculty of Science and Directorate of Curriculum Management and aimed at the Junior Science Olympiads was where Sebu’s idea for highlighting the beauty of mathematics was born.

The passion for their subjects is infectious in all three researchers. Each one listed the prospect of inspiring their audience as their top goal for the festival. Shaking up science communication by presenting it in a way we wouldn’t expect, through musical maths, theatrical economics, and artistic AI, provides an opportunity for researchers and citizens alike to see science through a new lens. One where progress seems brighter and kinder.