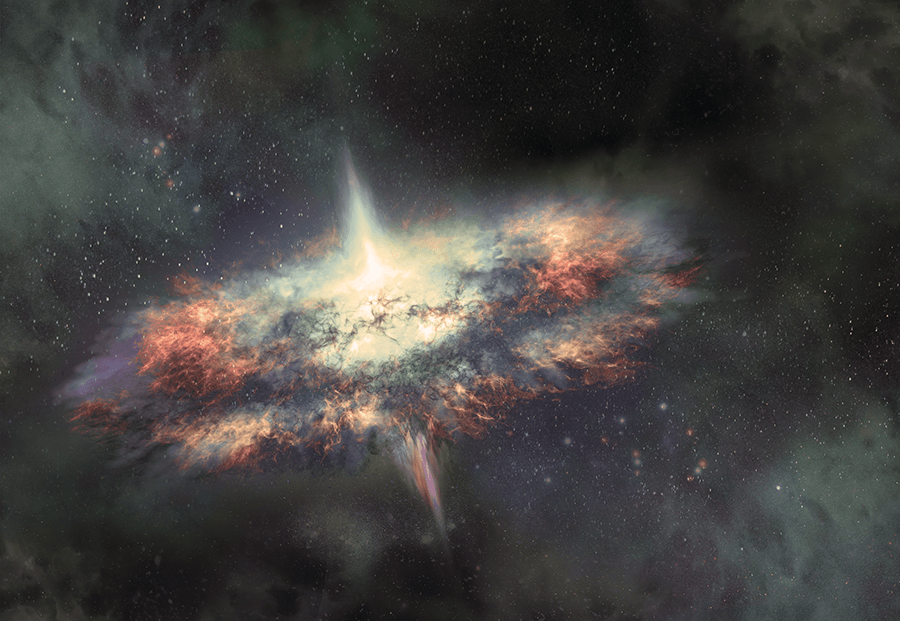

Earth is just one planet in a solar system that wanders around a galaxy. Each galaxy is unique in its own right, each composed of its special ration of dust, gas, and endless stars. What unites them all is the mysterious dark sky that they float in: the Universe.

A constantly growing expanse of space and time, the Universe’s attractive gravitational force is currently decreasing while its repulsive force is increasing. This repulsive force is referred to as dark energy. It is pushing galaxies apart at an increasing rate, bringing up a flurry of questions. Why is this happening? How does dark energy work? What is the role of magnetism?

To answer these questions and more requires the right tools. Improvements in instrumentation up until now have enabled astronomers to unveil many mysteries, not only in the visible region of our Universe where human eyes are sensitive to electromagnetic waves, but also beyond. This is done through various means. Optical telescopes, such as the famous Hubble Space Telescope, detect the intensity of incoming radiation in the optical band of the spectrum. Fundamentally, all celestial objects emit electromagnetic radiation, among them radio waves.

The observation of cosmic objects in these radio frequencies is defined as radio astronomy. Because radio waves penetrate dust, scientists utilise radio astronomy techniques to explore undetectable areas of space which cannot be seen using visible light by optical telescopes.

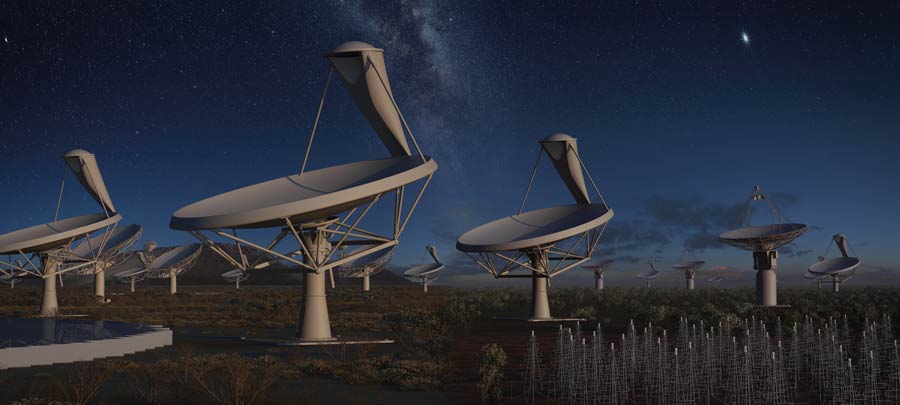

The project is an international effort to build the world’s largest multi radio telescope that will have a total collecting area of approximately one million square metres.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project is the largest project planned for the 21st century. It will see thousands of radio telescopes built in South Africa and Australia. It will enable unparalleled insights into the Universe. The project is an international effort to build the world’s largest multi radio telescope that will have a total collecting area of approximately one million square metres. SKA’s developers are building a system that would operate over a wide range of frequencies, and its size would make it 50 times more sensitive than any other radio instrument. It is set to be able to take images of the sky at up to 10,000 times the speed of current survey radio telescopes.

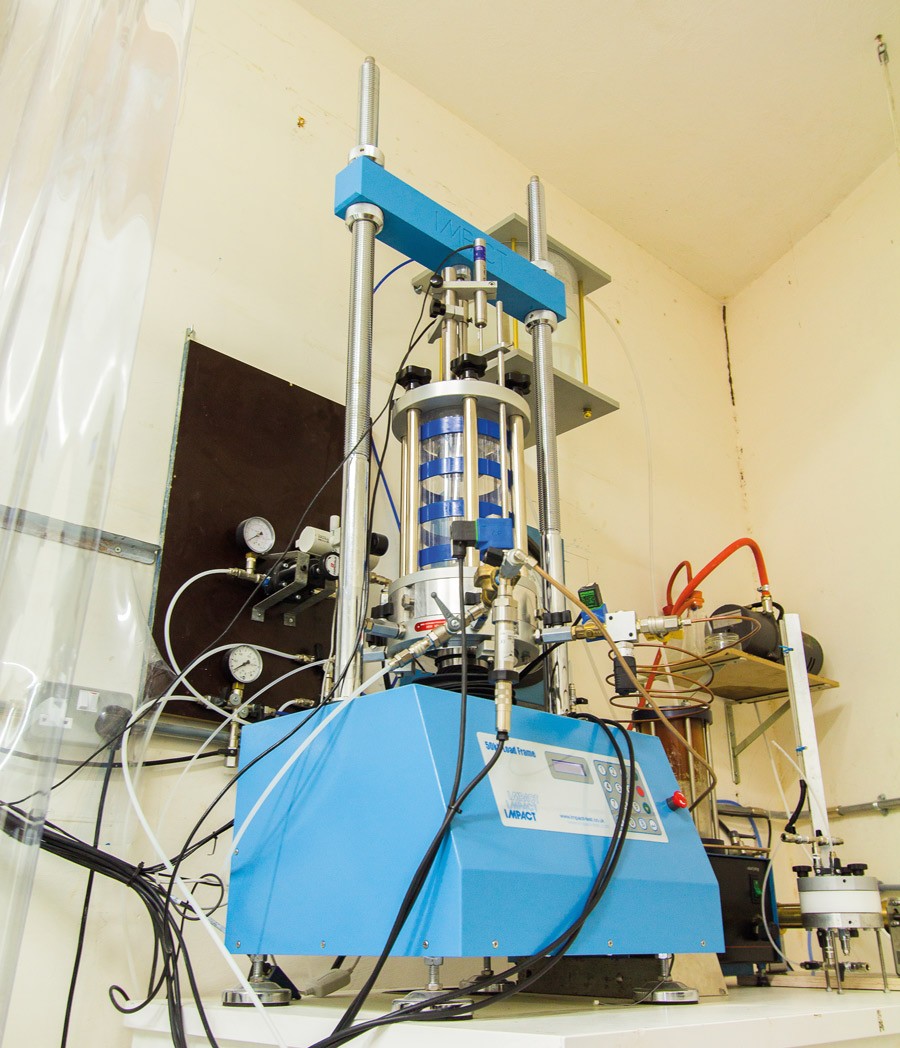

The University of Malta’s (UoM) contribution to the SKA project is being spearheaded by the Institute of Space Sciences and Astronomy (ISSA). ISSA Founder Prof. Kristian Zarb Adami, Faculty of Science Dean Prof. Charles Sammut, and Iman Farhat are developing an antenna which can be printed like a newspaper and can be rolled out like a carpet.

Unlike conventional antennas which are designed to work optimally at one frequency, the engineering prototype developed at the UoM can sense a large range of frequencies and is capable of running applications such as TV, wireless, Bluetooth, and near-field communications. This was also important because ISSA researchers are trying to detect the first atoms and molecules that were formed at the earliest stages of the Universe. This antenna is also intended to serve as a cost-effective element to cover remote locations for SKA.

The SKA project is scheduled to be built in phases, starting in 2018 and finishing in 2024. Even before the SKA is online, several thousand combined radio telescopes will be collecting and processing data equivalent to 100 times today’s global internet traffic per [unit of time].

The first small scale prototype antenna ISSA built had 256 elements and met SKA’s application and requirements. This was immensely motivating, especially when considering the high standards of this world-wide consortium. The initial success drove home the possibility of further in-depth studies.

ISSA has now embarked on building a large-scale version of the array (funded by the Technology Development Programme of the Malta Council for Science and Technology and Malta Communications Authority). The Malta array demonstrator is an implementation of two antenna arrays. Each array consists of 5,000 elements covering an area of 100 m2. The main aim of this is to test the array in an environment close to its real world conditions. The characterisation of the antenna array radiation pattern is being investigated using a far-field flying source. The system makes use of drones equipped with a transmitter and a dipole antenna that communicates with the array on test. The team is now working on this antenna to ensure a seamless performance.

SKA is a behemoth of a project, involving about 100 organisations across 20 countries. With it, scientists and researchers all over the world will be able to conduct transformational science in astronomical observation, breaking new ground with every step and redefining our understanding of space as we know it.

Key goals include challenging Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to have a closer look at how the very first stars and galaxies formed moments after the Big Bang. It could also potentially provide an answer to one of the greatest mysteries known to humankind—are we alone in the Universe?