Some look at the state of global politics and say the world has gone crazy. But dissatisfaction with the status quo has long been brewing. Dr George Vital Zammit tells us how and why it happened.

‘Look out for those who still want to hang on

Look out for those who live in the past

Get out and listen to the whisper

Because the times are changing fast’

Mike and the Mechanics, Word of Mouth (1991)

Rewind to July 2013. Newly appointed Pope Francis is visiting the most populous Catholic nation in the Americas, Brazil. Millions greet him, as expected. His security is ample, as expected. But the visit is tarnished by protesters who perceive the spending to be excessive. A year later, Brazil is knee-deep in preparations for the 2014 World Cup it is set to host. At the same time reports about ‘the high cost of the stadiums, corruption, police brutality, and evictions’ abound.

These two key occasions in Brazil’s history were characterised by anger and discontent. But such episodes are neither irregular nor isolated. Masses are moved by actions that undermine their well-being and will organise themselves to voice their disagreement. Many recent examples could be taken. From the protests in Venezuela against the Maduro regime, to the Women’s March on the morrow of President Trump’s inauguration, to the populist sentiments in Europe that threaten the EU. There is no indication that the curtain on public discontent will be closed any time soon.

We are now witnessing an uprising against the political norm.

The expression of change and desire for social justice can take various formats, from the ballot to the bullet. We are now witnessing an uprising against the political norm. Leaders who do not represent the conventional power structures have become more palatable with the electorate. This is the ‘globalisation of rage.’

We are living in an age where controversial candidates, at times with huge credibility gaps in their proposals, not only step forward to rattle the boat, but actually manage to win elections. The implications of such wins require deeper thinking. We have seen a rush to relegate such wins as the ‘new malaise’ or the ‘new wave of populism’ in modern democracies. And while this assessment may be right, in a sense, I argue that it is superficial. At best, it is a flawed understanding of a ‘post-liberal’ world.

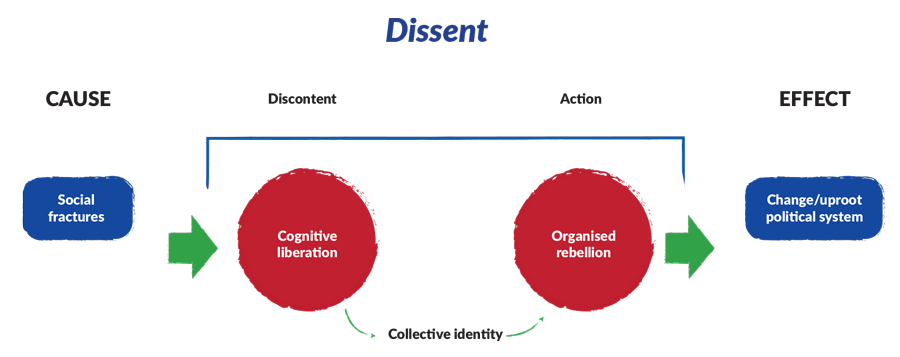

The theme of my argument is the politics of dissent: a state of conflict, intellectual and physical, individual, or in a group. Dissent, rather than a disruption of a state of order, can be considered a catalyst of change, an awakening against conformity, a protest against convention. Once this is contextualised, the world around us makes more sense.

Breaking things down

Lenin’s premise was that ‘politics begin where the masses are.’ This notion of politics skews the attention of politics away from the individual and towards a collective representation of society. Various political thinkers have contributed to the debate, offering conflicting views.

The tumultuous foundation of nations and the birth of their institutional architecture was subject to important political debates. As the dust settled, less attention has been devoted to the relevance of these structures. Some scholars argued that revolutions enjoy a ‘marginal existence’ in international relations literature, a vacuum now mitigated by a plethora of reflections on how phenomena like the Arab Spring or the Euromaidan revolution (also referred to as the Revolution of Dignity) inferred on the international system.

To understand resistance is to understand the exchange of power. Society remains ‘the expression of power relations.’ According to Michel Foucault, the problem with contemporary notions of democracy is that power now appears kind when it is not, whereas in the past, power was cruel, encouraging rebellion by the masses. This reflection still holds. However, it is also true that while revolutions can be subtle, as in the case of Brexit, protests can now take both a physical dimension (in public spaces) and a virtual dimension where people converge online to perpetuate dissent.

Society resents domination. According to the American political scientist Jack Goldstone, ‘when one expects a better life, and those expectations are frustrated, dangerous feelings of aggression and resentment against the social order arise.’ Whereas we expect democracy to be a political system that produces equitable and fair governments, we are also witnessing a number of political processes where democracy is considered the ‘culprit’ of unfavourable outcomes—take Brexit and the election of Donald Trump for instance (see schematic above). However, dismantling an accepted convention like democracy comes with a number of perils. Is there an alternative? The answer is no, even when it gives us its fair share of disappointments.

Understanding rage

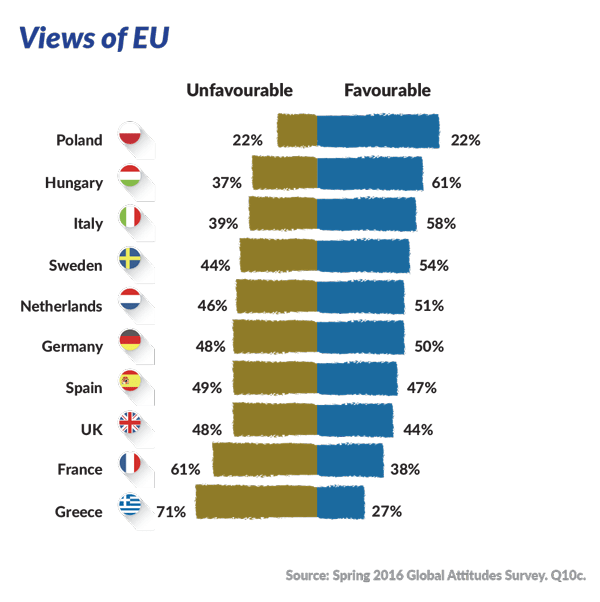

People react when they perceive that their dignity is being breached. During his intervention in the Davos Summit of the World Economic Forum, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte claimed that ‘too many countries (in the EU) are not doing what was promised— implementing reform.’ Why are we then so surprised that different segments of European populations are protesting against the EU?

The EU has undeniably been the most significant historical development after the Second World War. It has kept the peace throughout the continent, albeit not without turmoil, and opened an era of neoliberal institutionalism, that is, the functioning of ‘institutional machinery to facilitate cooperation among members in the security, economic, social, or related fields.’ What we are witnessing now is an increase in the disenfranchisement of the EU and what it represents. My belief is that the antidote is not more, but less Europe. An increasingly federal model (a United States of Europe), is more likely to increase resentment and discontent.

In her essay On Violence, Hannah Arendt treats bureaucracy as an alienating variable in the nation state. She describes it as ‘an intricate system […] in which no man, neither one nor the best, neither the few nor the many, can be held responsible, and which could be properly called rule by Nobody.’ If we shift this accusation to the EU, we are left with a gigantic bureaucratic structure, with which people cannot easily identify.

Moreover, the notion that the EU is a gravy train has gained currency in recent years.

In 2016 a multi-nation survey from Pew Research Center showed that Euroscepticism is on the rise across Europe. Sociologist Anthony Giddens argued that the EU is a ‘functionalist enterprise, driven by results rather than affection, let alone passion.’ It will either ‘move closer to its citizens […] or it will not survive in recognisable form at all.’

But, wait. Not all is lost. According to Joonas Leppänen, dissent is ‘positive and constructive for many reasons: it fosters democratic citizenship, it aims to remove injustices, and it may improve the institutional framework and strengthens participatory parity in society.’ The view here is that dissent should be welcomed, rather than disdained. Political leaders need to heed signals where possible, avoiding blackmail if key values are challenged.

Solutions?

Solutions?

In her recent work Agonistics, Chantal Mouffe posits that the search for consensus ‘and the hope for a perfectly reconciled and harmonious society’ is futile. Thinking can never be homogenised, and a pluralist society can never ascribe to a hegemonic political platform. What Mouffe postulates is that the wave of protests ‘should be seen as reactions to the lack of agonistic politics in liberal democracies’ calling for ‘a radicalisation, not a rejection, of liberal democratic institutions.’ The paradox today is that we have more tools to communicate, yet less predisposition to listen to each other. More tolerance to diverse views and transparent political processes will only make democracies stronger.

The next step would be an injection of dignity. We live in an age where the state (and its people) is at the service of the economy, and not vice-versa. This course needs to be abandoned if we truly believe in sustainable well-being. When the status quo becomes incomprehensible to fathom, unbearable to withstand, social disorder is inevitable. The January Oxfam Briefing Paper An Economy for the 99% estimates that just eight men own the same wealth as the poorest half of the world. The unrestrained race to enrichment has made globalisation a multiplier of inequalities rather than a means for development and well-being. Global politics professor Barry Gills argues that ‘the death of polities, via the death of our ideals […] is the inevitable outcome of a process wherein capital and the market alone determine the restructuring of economic, political, and cultural life, making all other alternative values or institutions increasingly redundant.’

Depoliticising politics

Depoliticising politics

Unless society is allowed to foster a truly democratic environment, extreme views on the ideological spectrum will find more fertile ground. Political parties (and their influence) play a crucial role in the functioning of democracies yet their reach often suffocates the free exchange of ideas. In The Theory of Communicative Action, German sociologist Jurgen Habermas argues that ‘the public sphere of modern society does not allow a genuine democratic debate.’ Politics, if divested of excessive and blind partisanship, would be able to deliver much more. The political space is often ‘hijacked’ by mainstream political parties allowing little space for experimentation of new ideas. As political scientist Andrew Heywood reminds us, ‘no tradition possesses a monopoly of political wisdom.’

We live in a reality where policies are articulated (tweeted) in 140 characters. Such communication has succeeded in widening reach, but often it narrows the grasp of the very message it intends to convey. Connectivity has been drastically enhanced, but so has alienation and detachment. The political reality of today gives more prominence to form than to content, leaving our systems of government weaker and unable to think and plan for the future. The adage ‘the future is now’ has no place in politics. Past-present-future are separate compartments, connected, but not interchangeable.

Politics is to remain a vehicle for social justice. Whenever dissent leads to seismic changes, we are never fully prepared for its ramifications. As Goldstone claimed, revolutions are like earthquakes, when one occurs, we try to make sense of it and why it happened. But when the next one happens, will we still be caught by surprise?

www.facebook.com/politicsofdissent

Further Reading

-

Pankaj Mishra, ‘The Globalisation of Rage—Why today’s Extremism looks familiar’ in Foreign Affairs Magazine, 95(6), pp. 46-54

-

Arendt, H. (1972), Crises of the Republic, Harcourt Brace & Company, p. 137

-

Giddens, A (2014), Turbulent and Mighty Continent—What future for Europe?, Polity, pp. 4-5

-

Leppänen, J. (2016), “A Political Theory of Dissent: Dissent at the Core of Radical Democracy”, Dissertation submitted at the Faculty of Social Science, University of Helsinki, Finland.

-

Heywood, A (2015), Political Theory—An Introduction, 4th ed., Palgrave, p. 4

Solutions?

Solutions? Depoliticising politics

Depoliticising politics

Comments are closed for this article!