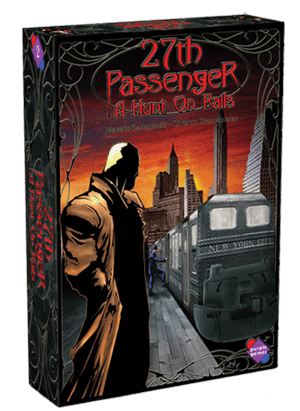

27th Passenger

I thought I hated deduction games. A friend of mine had purchased The Resistance and we played it till kingdom come. Everyone loved it, except me. It was too much a social exercise and too little a game. This is not necessarily bad, it just made the game extremely different with different groups, and it didn’t work with some of them. I assumed that this was true for all deduction games; 27th Passenger proved me wrong. 27th Passenger is about a group of assassins on a train. They all want to kill each other, but not the civilians. Of course, all players have a disguise ranging from a tough gangster to a sweeter schoolgirl.Continue reading