The Humanities, Medicine, and Science (HUMS) Symposia at the University of Malta offer a unique platform where experts from diverse fields come together to explore a single theme from multiple disciplinary perspectives. This academic year, the HUMS first event, entitled ‘The Sun’, provided an interdisciplinary deep dive into the scientific, cultural, and existential significance of our closest star.

Continue readingWhy Don’t Ants Take Fall Damage?

Do you ever recall those moments in nature, where tiny insects seem to mistake you for a tree? Not only do they walk vertically upwards with incredible grip, but as they are brushed off and fall to the ground, they just nonchalantly walk away. No big deal. Except, when put into perspective, an ant falling from your arm is as though a person fell off a rooftop and walked away untouched. Why do small insects, and ants specifically, never seem to take any fall damage?

Continue readingSounds of silence

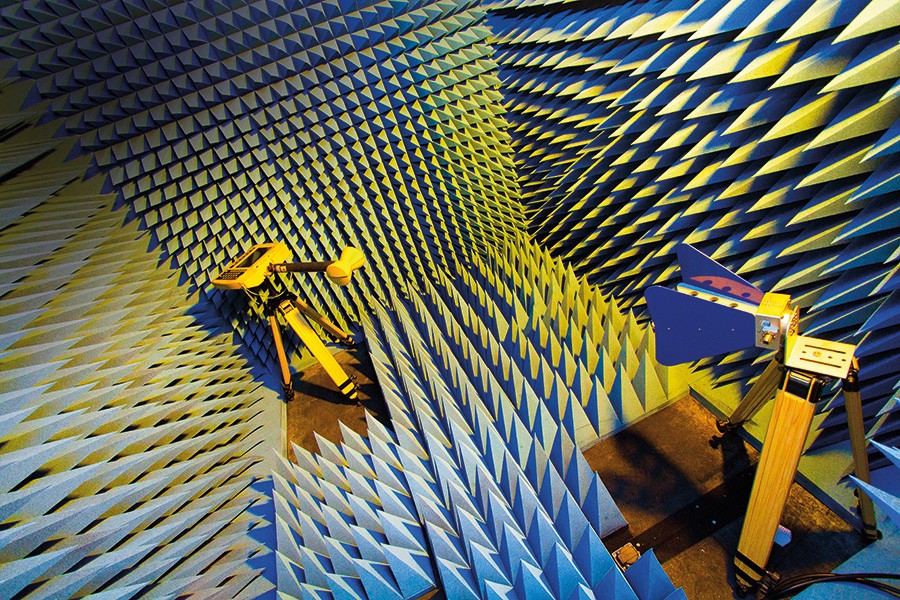

| Tech Specs |

Dimensions: 2.5m x 2.5m x 2.5m Weight: 2 tonnes Frequency: 800MHz – 18GHz Price: €140,000 |

Everything in the world can emanate sound waves. These are invisible, consisting of vibrating particles in the air which can strike our eardrums, which lets humans hear. But what if you want to measure waves coming from a particular object?

An anechoic (echo-free) chamber is a heavy, metal enclosure with inner walls covered in foam wedges made from a radiation absorbent material. Any emitted sound or electromagnetic waves become trapped between these wedges until all their energy is completely absorbed. The chamber also eliminates all noise from exterior sources. Simply put, speak in an anechoic chamber, and you will hear the pure sound of your voice echo-free. The volume of these chambers is dictated by the size of the objects as well as the frequency of the device under investigation. They can be anywhere from the size of an old television monitor to the size of an aircraft hanger.

So what are they used for?

Testing electronic devices that radiate acoustic or electromagnetic waves and mapping out radiation patterns of antennas. It’s useful for systems such as satellites, radars, computers, missiles, and vehicles. Measurements aim to determine characteristics such as susceptibility, system sensitivity, effective radiated power, tracking ability, and comparability. The chambers can also be used to evaluate the effect of electromagnetic fields on human tissues, a type of experiment that has already been carried out in the University of Malta (UoM) anechoic chamber. Manufacturers of electronic equipment are required to conduct electromagnetic compatibility and immunity testing prior to placing a device on the market. This ensures that they won’t generate too much electromagnetic disturbance and will also be sufficiently immune from fields generated by other sources. Due to this new equipment, the UoM will be able to provide pre-compliance testing services to companies, which will prepare their devices for expensive compliance testing in certified laboratories, saving them a good sum of money.

Radio Telescope

Malta now has a radio telescope. This is a great step forward for the University of Malta as it helps speed up research.

The Department of Physics, Faculty of Science and the Institute of Space Sciences & Astronomy (ISSA; both at the University of Malta) have just acquired a 5.3m dual-reflector parabolic dish, as part of a European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) project to extend postgraduate research lab facilities. The radio telescope will now allow students and researchers to study celestial objects such as the sun or the centre of the galaxy through the radio waves they emit.

| Quick Specs |

| Dish diameter: 5.3m

Feed horns: L-Band and K-band Gain: 44 dBi @ 4GHz Observing modes: Continuum and line observation Total weight (including pedestal): 1900 kg Surface accuracy: 0.5mm PC-based automated control unit |

When pointed to a radio-loud celestial object (an object which emits large amounts of radio waves, such as the sun), the telescope will receive radio waves from these sources and convert them to voltage readings in the feed. The converted signal is then transmitted to a digitiser that converts these signals into bits and bytes.

When pointed to a radio-loud celestial object (an object which emits large amounts of radio waves, such as the sun), the telescope will receive radio waves from these sources and convert them to voltage readings in the feed. The converted signal is then transmitted to a digitiser that converts these signals into bits and bytes.

The digitised signals are then processed and broken down into the different frequency counterparts (similar to what a car radio does with the radio waves it receives from its antenna), which allows for continuum observation of the skies above. The telescope provides a test-bed for several research initiatives being undertaken at ISSA.

Some of its specialisations include improving the hardware and software processing back-ends for radio telescopes. The on-site telescope can speed up this sort of research immensely. ISSA is part of the largest radio telescope project in the world: the SKA (Square Kilometre Array).

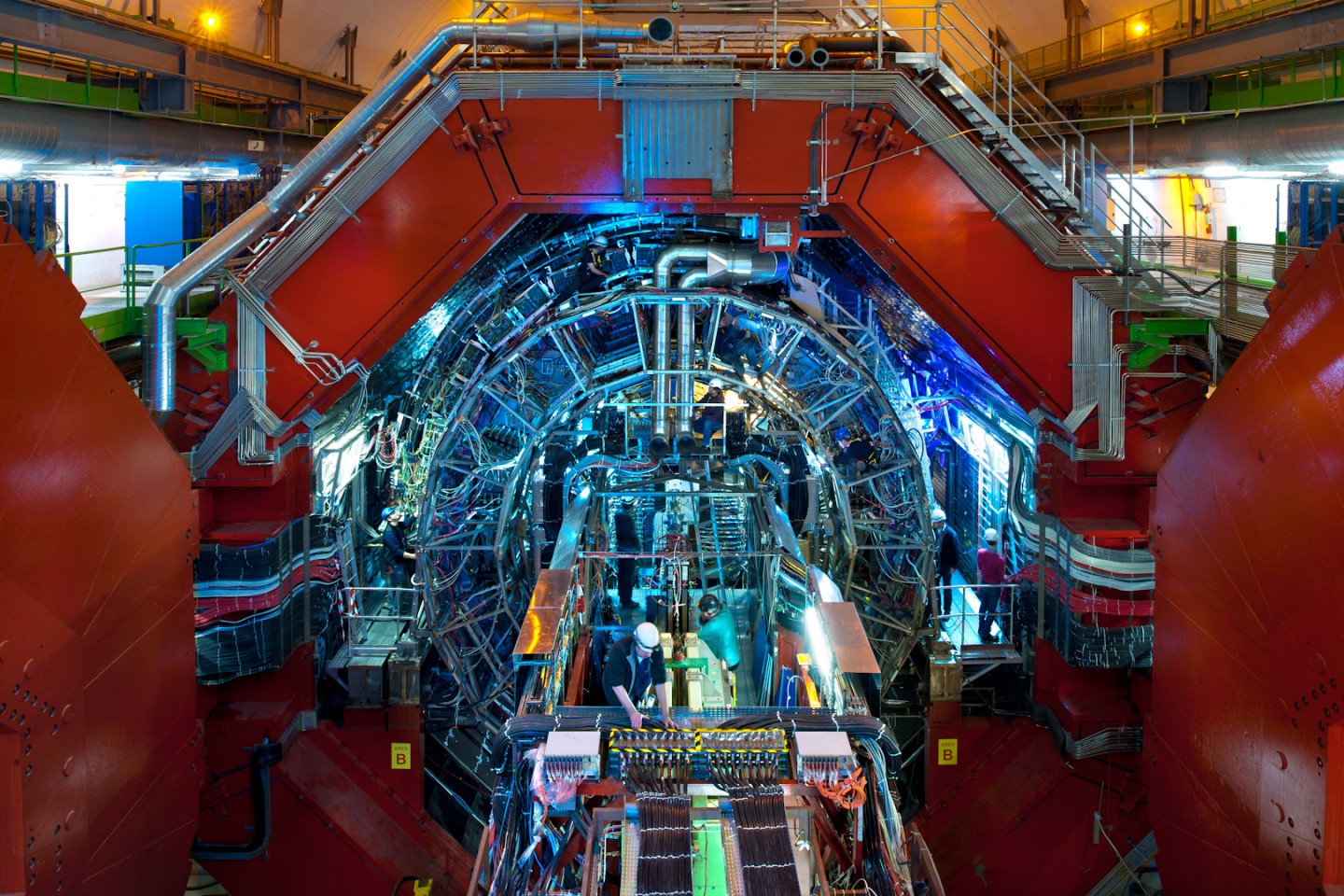

ALICE’s Adventures in Switzerland

Hidden 175 metres below the Franco-Swiss border lies a feat of human ingenuity: the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). The LHC is the largest scientific instrument ever constructed, providing mankind with the ability to begin unravelling the very fabric of the universe and everything around us. Now, following long established links with the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN), University of Malta has signed a memorandum of understanding for its scientists’ collaborate with the latest set of experiments at the LHC. Words by Scott Wilcockson. Photography by Edward Duca.

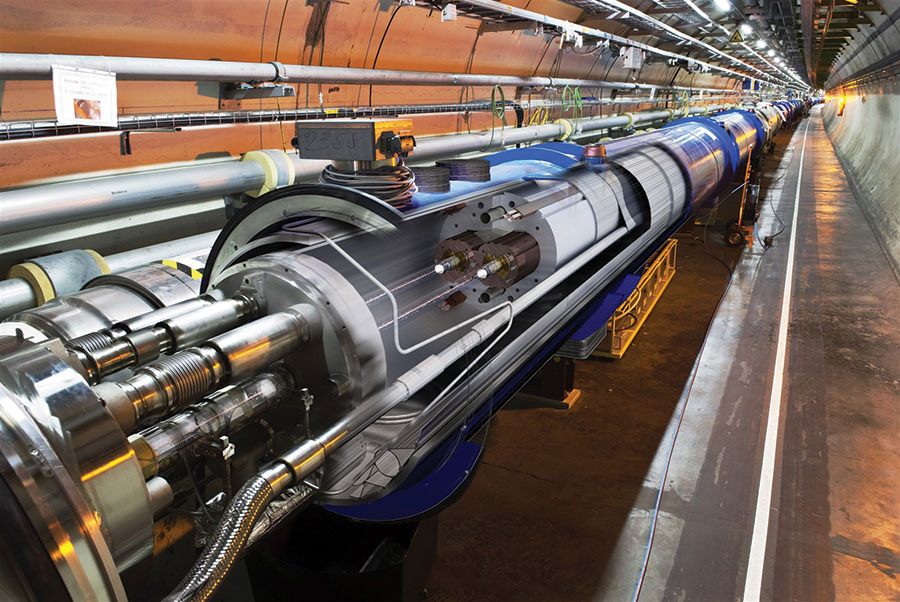

Crash Testing: the Largest Experiment on Earth

Under Europe lies a 27 km tunnel that is both the coldest and hottest place on Earth. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has already found out what gives mass to all the matter in the Universe. It is now trying to go even deeper into what makes up everything we see around us. Dr Marija Cauchi writes about her research that helped protect this atom smasher from itself. Photography by Jean Claude Vancell.

Under Europe lies a 27 km tunnel that is both the coldest and hottest place on Earth. The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has already found out what gives mass to all the matter in the Universe. It is now trying to go even deeper into what makes up everything we see around us. Dr Marija Cauchi writes about her research that helped protect this atom smasher from itself. Photography by Jean Claude Vancell.

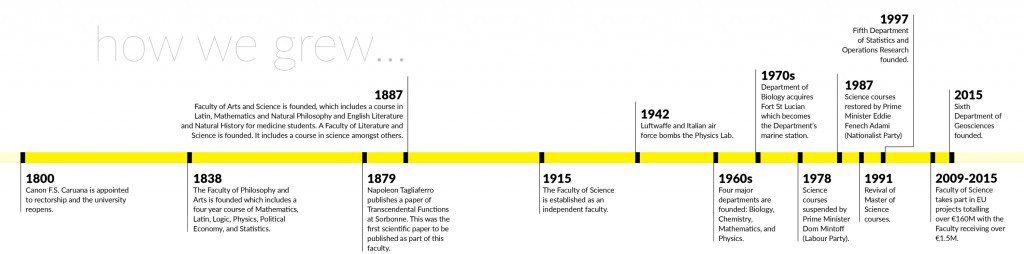

A Faculty Reborn

During the mid-1970s, the Faculties of Science and Arts were closed down, and the Bachelor programmes phased out. Most of the foreign (mainly British) academics left Malta, as did some Maltese colleagues. Those few who stayed were assigned teaching duties at the newly established Faculty of Education and Faculty of Engineering. Relatively little research took place, except when funds were unneccessary, and it is thanks to these few that scientific publications kept trickling out.

In 1987, the Faculties of Arts and Science were reconstituted. The Faculty of Science had four ‘divisions’ which became the Departments of Biology, Chemistry, Physics, and Mathematics. In the same year, I returned from the UK to join the Faculty.

Things gradually improved as more staff and students joined. However, equipment was either obsolete or beyond repair. The B.Sc. (Bachelor of Science) course was re-launched with an evening course. Faculty members worked flat out in very poor conditions. The Physics and Mathematics building was still shared with Engineering. Despite these problems, we had a Faculty and identity. Nevertheless, we wanted our courses to be of international repute—our guiding principle.

During the 1990s, yearly budgets had improved slightly along with experimental facilities. Computers and the occasional capital investment helped immensely. Research output increased, as did student numbers, while postgraduate Masters and Ph.D. students started to appear.

Since 2005, some faculty members have been working hard to secure European Regional Development Funds (ERDF) by submitting proposals to reinforce our research infrastructure. A total of six projects were approved with a combined budget of nearly €5 million. This has resulted in new, state of the art research facilities and an exponential increase in research output, bolstered by additional academic staff and research student numbers of close to 80.

Students are now organised and active through S-Cubed, the Science Students’ Society. This leading organisation is one of the three faculty pillars: the academic and support staff, and the student body. Together, we have made giant strides and the future looks bright.

Special thanks to Prof. Stanley Fiorini who helped us compile our timeline, aided by Prof. Josef Lauri.