Moving to Malta

Our childhood years are meant to help us develop our sense of identity, belonging, culture, and home. But what happens to those for whom childhood is dominated by moving to a new country with a new language, culture, and social norms? Prof. Carmel Cefai speaks to Becky Catrin Jones.

It’s a small world these days. Developments in technology and transport mean it’s much easier to pack your bags and head off for a fresh start in a foreign land. For many, the destination is Malta. As a beautiful island in the Mediterranean Sea with a booming economy, it is no surprise that it’s drawing the attention of bright sparks and aspiring families from Europe and beyond. In fact, Malta currently boasts the fastest growing EU population.

Of course, it’s not always through choice that you might find yourself leaving your homeland behind. Humanitarian crises and ongoing wars in North and sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East have seen thousands set sail under the most treacherous conditions in search of safety. For this population, Malta is often the first port of call between the dangers of home and the promise of hope in Europe.

It seems strange to group these populations together, given the stark differences in the journeys that bring them to Malta and the life they seek here. But together, this influx of people has contributed to a sudden rise in interculturalism, where people from different backgrounds interact and influence one another. This is a reality all parties are having to adapt to.

Even in a fairytale scenario, childhood is challenging. Growing up when you’re far from home, look different to everyone around you, and don’t speak their language, makes the challenge reach a whole other level. Children’s wellbeing is an increasingly important and emotive topic to study in Malta, which is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. A team of researchers from the Centre for Resilience and Socio-Emotional Health (University of Malta), set out to explore the situation. They questioned: How do you settle into a new home and identity when you are still trying to figure out who you are and where you are from?

Finding the voices

Children are often a silent group. When analysing the wellbeing or effect of migration on a population, they are usually spoken for by adults. For this study, however, Prof. Carmel Cefai and his team wanted the child’s voice as well. The scope of the study was ambitious; every single contactable, non-Maltese child living in Malta was invited to take part and share their experiences. But this was a challenge.

‘Identifying and obtaining access to foreign children from age zero to 18 was not easy… Some schools suffered from research fatigue and did not wish to participate; whilst translation of instruments and data and use of interpreters drained the limited budget we had for this project.’ Maltese children were contacted and invited to participate too. After all, they are as affected as anyone else when around one in ten of their schoolmates are not Maltese.

The study focused on four main areas; social interaction and inclusion, education, subjective wellbeing and resilience, and physical health and access to services. They covered the experiences of children up to 18 years of age, from various schools, who were either settled into their own family houses or still in open shetlers following a difficult journey to Malta. They also aimed for a balance in migrants’ nationalities; European, North American, African, Middle Eastern, or East Asian; as the experiences of each population are understandably different. Cefai and his team found that the experiences of migrant children in their everyday life are quite positive. In some areas, even more positive than those of Maltese children, with only 8% reporting difficulties in their psychological wellbeing compared to 10% in the native population. Overall, they found that migrant children feel safe, listened to, and cared for by the adults in their communities. Despite the language barriers, most feel like they have a support network, and enough friends though more often than not those friends are other foreign children, not Maltese.They are able to keep up at school, and generally do as well as their Maltese peers, with teachers reporting high levels of engagement.

Adapting to a new world

All is not rosy. Bullying in schools is quite common, though less frequent than that reported by native Maltese children. One in five migrant children also do not feel they have enough friends.

Younger children seem to be more included and engaged than secondary school ones, and in general females fared better in the study than male classmates. That said, age and gender weren’t the main influencers when it came to predicting how well the children engaged at school and in their communities. ‘The study suggests that there are different layers of reality, with the big picture hiding the socio-economic, psychological, and social difficulties encountered by a substantial minority,’ remarks Cefai.

Unsurprisingly, those who speak Maltese feel more engaged than those who don’t, and those who aren’t confident in English are in an even worse position. However, the factor producing the biggest differences between the overall wellbeing, health, and education of the children is their country of origin. ‘The health, wellbeing, and relative comfort enjoyed by many children of European economic migrants contrast sharply with the poverty, poor accommodation, psychological difficulties, learning difficulties, and experiences of discrimination of many children from Africa and the Middle East’, says Cefai. Western Europeans and American children scored highly over all criteria, whereas African and Middle Eastern children are far more likely to be lonely or suffering from social or economic difficulties.

They are more likely to be less proficient in English, which leads to difficulties in making friends with children from other cultures and which also contributes to problems in their education. Although they are generally nourished by their spiritual and religious communities, in all other areas these children report social and emotional difficulties and are also more likely to report facing prejudice and discrimination. Healthcare proved problematic; many parents and children worry that they are subjected to discrimination whilst using services, or do not have enough information to use them in the first place.

A land of opportunity

Despite the additional challenges that these particular migrant children face, the overriding feeling is one of acceptance and hope. Even children in open centres view Malta as a land of opportunity, even when some are in suboptimal housing and lack basic necessities. What children in open centres do not perceive is Malta as their home. Better living conditions in the community, more cultural sensitivity, and openness to interculturalism may help to reduce the feeling of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

So what do Maltese children think? Again, the overall conclusions show that children are open, tolerant, and welcoming of this dramatic and quick rise in multiculturalism that has happened. However, on closer inspection, it seems that there is still a way to go before we can truly call ourselves an open and accepting society.

Relatively few Maltese children have many foreign friends, preferring to spend time with native peers. This hesitation is stronger in children who aren’t from a mixed community, whereas children in independent schools and more exposed to foreign children seem more at ease with the idea that the future might be even more multinational and intercultural. As many as one in three Maltese children also report feeling unsafe in culturally diverse communities, and worry about potential negative consequences of these changes in the future. There also appears to be particular prejudice against children from Africa and the Middle East in contrast to children from Europe, the US, Canada, and Australia.

What has become clear is that both foreign and native children could do with some reassurance. So what do Cefai and his team suggest we can work on to help everyone embrace this new culturally diverse reality?

A united future

‘[We need] to address the needs of marginalised and vulnerable children, particularly those coming from Africa and the Middle East’, says Cefai. There’s also a lot both populations could learn from each other; caring for their environment, sharing cultures, or even adopting healthier lifestyles. By encouraging more open and judgement-free spaces to play, learn, and share, we’ll take away the ‘us’ and ‘them’ ideology from a young age and replace it with one of acceptance, curiosity, and openness to new ideas. This will help prevent the dangerous spiral of segregation and ghettoisation, seen all over Europe.

Cefai suggests a space for more positive role models for those migrant children thrown into a foreign culture that doesn’t seem to have space for them. Having teachers, healthcare workers, or even political representatives who have similar backgrounds will foster this inclusive nature, showing that everyone has a voice when it comes to working together to make this country a home for all.

There’s work to be done with Maltese children. ‘Whilst it is encouraging that the majority hold positive attitudes towards interculturalism, it is worrying that as they grow older children’s attitudes tend to become less positive,’ says Cefai. ‘It’s our responsibility to ensure that educators, community leaders, and parents of Maltese children are part of a national initiative to embrace interculturalism.’

Although overall a positive study, Cefai and team have shown we still have a way to go until every child in Malta feels safe, happy, and at home. And in this ever-changing and diverse environment, Malta has real potential to be an example to its neighbours on how a successful multicultural society can work on every level. These children are our future.

I <3 potato

Plant-based diets are going mainstream all over the world. Cassi Camilleri sheds light on the local vegan movement and how reducing our meat consumption can benefit us all.

Some label the rise of plant-based living as evidence of ‘trend culture’. And they’re not all wrong. Traditional media bombards us with countless headlines on the topic’s pros and cons. Hard-hitting advocacy films like Cowspiracy and Forks over Knives expose the horrors of the meat industry. Social media influencers share their experiences with the diet, turning it into lifestyle content. And now the market is following suit with vegan and veggie lines and options popping up everywhere.

In 2016, an Ipsos MORI survey for the Vegan Society identified that 3.25% of adults in the UK never eat meat in any form as part of their diet, equating to roughly 540,000 people. Vegan January—commonly known as Veganuary—is growing in popularity. This year, a record-breaking 250,310 people from 190 countries registered for the month-long vegan pledge. And Malta is no exception.

While the official number of people following a plant-based or vegan diet are unavailable, interest is clear. Facebook pages Vegan Malta and Vegan Malta Eats have a combined following of over 16,500 people.

The reasons behind people’s decision to take up veganism are various, however three main motivators keep being cited: health benefits, ethics, and environmental concerns. For vegan business woman Rebecca Camilleri the process was natural and gradual. ‘There was no real intention behind it for me. But after a couple of months of following this diet, I noticed that my energy levels were better than before, and this encouraged me to learn more on how I needed to eat in order to nourish my body with the right nutrients to sustain my active lifestyle.’

Researcher and nutritionist Prof. Suzanne Piscopo (Department of Health, Physical Education, and Consumer Studies, University of Malta) confirms that ‘moving towards a primarily plant-based diet is recommended by organisations such as the World Health Organization and the World Cancer Research Fund, for health and climate change reasons.’

Oxford academic Dr Marco Springmann has attempted to model what a vegan planet would look like, and the results are staggering. According to his calculations, should the world’s population switch to a vegan diet by the year 2050, the global economy would save $1.1 trillion in healthcare costs. We would also save $0.5 trillion in environmental costs, all while slashing greenhouse gas emissions by two-thirds.

Despite all this, veganism has earned itself quite a few enemies along the way. The vitriol thrown back and forth across both camps is shocking. Relatively recently, UK supermarket chain Waitrose came under scrutiny after magazine editor William Sitwell responded to plant-based food article ideas from writer Selene Nelson with a dark counter offer—a series on ‘killing vegans’. Sitwell was since forced to resign. Nelson posited that the hostility stems from ‘a refusal to recognise the suffering of animals. Mocking vegans is easier than listening to them.’

Abigail Higgins from American news and opinion website Vox agrees that guilt plays a role in the hatred aimed towards veganism, but also proposes that the whole movement ‘represents a threat to the status quo, and cultural changes make people anxious.’ This notion is based on research on intergroup threats and attitudes by US researchers Walter G. Stephan and Cookie White Stephan.

It however remains a reality that some of the loudest voices in veganism in the past have been militant. Some have invoked hatred and threats towards those that they perceive not to be sufficiently aggressive in promoting the cause. Piscopo calls for a respectful discussion.

‘Food is not only about sustenance and pleasure, but has symbolic, emotional, and identity value. Take meat for example. Some associate it with masculinity and virility. Others link it to food security as meat was a food which was scarce during their childhood. Some others equate it with conviviality as meat dishes are often consumed during happy family occasions. What is important is that we do not try to impose our beliefs, thoughts, and lifestyle on anyone.’

The way forward is a ‘live and let live’ approach, according to Rebecca Galea. When her journey started she had people ‘staring strangely at [her] food’. Even her family didn’t take her seriously. ‘They were very sceptical as their knowledge on veganism was very limited at the time,’ she remembers. Now, seeing the effect the switch has made to Rebecca’s life, her positive choices are naturally impacting theirs. ‘Everyone is free to make their choice,’ she says. Embodying the philosophy of leading by example, Rebecca has even set up her own business making delicious vegan nut butters, spreads, and more, to great success. ‘The more vegan options are available [in Malta], the more people will be attracted to learning and accepting the benefits of veganism. This might also lead to them following a vegan lifestyle!’

With that, and sharing valid, up-to-date research-based information, as Piscopo suggests, it seems there is no stopping this ‘trend’. And who would want to when veganism can lead to a lower carbon footprint and better health for everyone?

I am online

We’re always warned about what personal details we share on social media. But what does the language people use on platforms like Facebook and Twitter tell us about their wellbeing? Words by Dr Olga Bogolyubova.

Today being an Internet user means being a social media user. The two have become synonymous.

According to the Global Web Index report, there are now over three billion people worldwide using at least one social networking site. The average Internet user has eight social media accounts and is active on at least three platforms. In our contemporary world, most of us spend a significant chunk of our lives online.

This is a modern reality: we access information online, purchase goods and services online, search for jobs online, follow professional interests online, schedule events online, invest in relationships online (some of them purely virtual), and then spend the remaining idle time browsing through our news feeds.

Humans are social creatures, and like other big apes we care about hierarchies and group status. This is reflected in our behaviour on social media, where we actively engage in impression management. We select aspects of our lives to present online in the hopes that they will bring us more benefits, while editing out other parts that could cause negative consequences.

We want to look happy, popular, rich, and successful, or if that doesn’t work, at least try to come across as dramatic or alluring. But in a world where the line between reality and the digital world continues to blur, can we really separate our real-life characteristics from our online persona? Can we effectively hide aspects of our offline identity when online? Are we as good at concealing our true selves as we think we are?

Going deep

A few years back, Dr Michal Kosinski and his team set out to find answers to the above questions. They sought to determine if it would be possible to predict individual characteristics (such as age, gender, sexual orientation, and so on) and personality traits from Facebook Likes.

Over 58,000 people volunteered to take part in the study and provided their Facebook Likes, demographic data, and answers to a set of psychometric measures.

Ethnic origin and gender were predicted from Likes with the highest level of accuracy (95% and 93%, respectively). Prediction of religion, political preferences, and sexual orientation was also good, with 75% to 85% accuracy. However, predicting personality traits turned out to be somewhat more difficult.

In psychology, personality traits are described as characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours and, by definition, these are latent variables, meaning that they are not directly observable but derived from answers to a set of questions. Even so, Kosinski’s research team did manage to demonstrate significant connections between the study participants’ personality traits and their Facebook Likes, with the trait of Openness showing the best predictive potential.

The study has attracted a lot of attention. Other researchers have since been attempting to predict individual characteristics from various features of social media profiles. At first glance, some of the findings may look strange or even absurd. For instance, in one of the studies aimed at predicting personality traits from profile pictures, it was found that extroverted people are less likely to have profile pictures with nostrils showing. Sounds ridiculous… but it actually makes sense if you think about it. By definition, extroverted individuals are more likely to be mindful of other people’s perceptions of them, more likely to see themselves from another’s point of view. As a result, they’ll post better selfies and profile pictures when compared to introverts, who are more likely to upload casual snapshots as profile pictures.

This observation shows that we are unable to control the little details of our behavior. There as so many minute variables involved that it is impossible for us to keep track of them all. A lot of non-vital and therefore ‘unnecessary’ information slips through, yet it reveals a lot about us. This is also found in language. While we usually have no trouble controlling what we say, it is much harder to control how we speak. The topics of our conversations with friends and strangers are firmly under our control, but our use of pronouns and articles in everyday conversations is not. The style of our language is invisible to us.

Honing in on the invisible

James Pennebaker, Professor of Psychology at the University of Texas, USA, was among the first behavioural scientists to propose computational approaches for the study of these invisible, functional components of language.

Pennebaker’s research demonstrated that it is these ‘stealth’ elements that connect deeply with our psychological makeup and state of mind. His ideas provided a starting point for a lot of current social media-based research. After all, our online presence is still largely text-based and rooted in language, and it is only natural that a lot of social media research is based on linguistic analysis.

Many studies are exploring predictors of how online language is being used. For instance, in a recent Facebook-based study, conducted in collaboration with my colleagues from St. Petersburg State University, Russia, we explored connections between subjective wellbeing (i.e. level of satisfaction with one’s life and positive emotionality) and language used in wall posts.

We were able to show that individuals with lower levels of subjective wellbeing are more likely to use ‘should statements’ in their language. In psychotherapy there is a long-standing tradition to regard ‘should statements’ as a type of irrational thinking associated with distress and mental health problems. It is interesting that we were able to demonstrate the relevance of these classic, pre-Internet theories to the contemporary world.

Identifying markers of mental health problems in online language is another important strand of research. Anxiety and mood disorders are the most common mental health conditions, responsible for a significant burden worldwide. They are also treatable, so early identification is vitally important, and social media may provide a platform for screening, psychoeducation, and connection to treatment (including affordable digital interventions). Research can change these citizens’ lives.

Social media-based research on mental health disorders has consistently found an increased use of first person pronouns (I, me) by people with depression. The finding reflects the painful self-centeredness of the mind in mental illness. Some other findings include observations on language use in post traumatic stress disorder, seasonal affective disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder, as well as on identification of suicide risk.

Social media can be risky, but is it the monster we are seeing splattered all over mainstream media? Research can help build systems that bring mental health interventions to low resource regions, and it can aid in identification of suicide risk and risk of violence. Ultimately, it can promote healthy living and save lives.

Public health priority: Type 2 diabetes mellitus

What is Malta doing to address this very prevalent problem? Dr Sarah Cuschieri writes about a project called SAĦĦTEK.

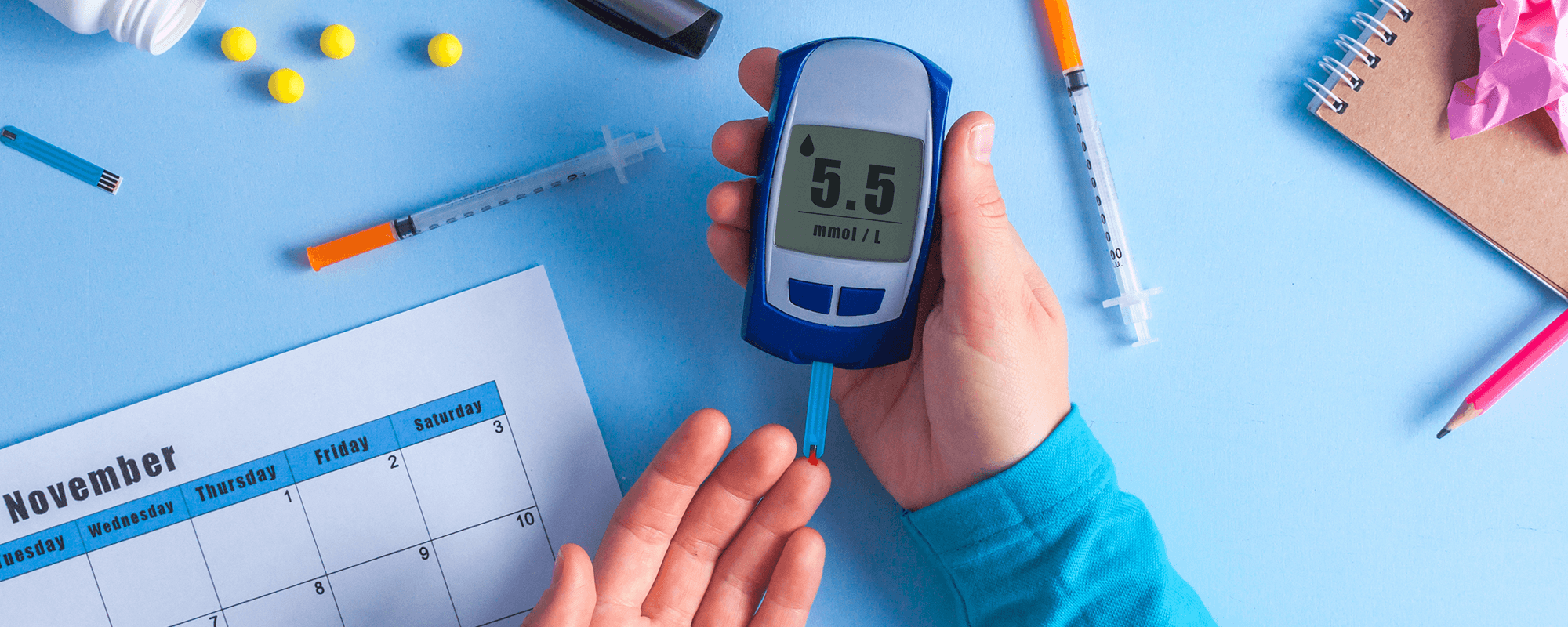

In Malta, diabetes has been a health concern since 1886. In 1981, the World Health Organization performed the first national diabetes study in Malta and reported that the total prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is 7.7% (5.9% previously known diabetics and 1.8% newly diagnosed diabetics).

Since then, we have seen that percentage increase through self-reported questionnaire studies such as 2008’s Maltese European Health Interview Survey, which reported a T2DM prevalence of 8.3% in the population aged between 20 and 79. In 2010, it rose again to 10.1%, according to the Maltese European Health Examination Survey. And while this information is definitely useful, it cannot help researchers and doctors investigate what elements contribute to the diabetes epidemic in Malta.

The economic boom over the last four decades has permanently changed the Maltese Islands. With it came a change in lifestyle habits, like car use and diet, and an influx of different cultural and ethnic populations settling on the islands, which meant that it was time to update our understanding of T2DM in Malta; its prevalence, determinants, and risk factors.

I undertook the project “SAĦĦTEK – The University of Malta Health and Wellbeing study” to find out more about T2DM in Malta. SAĦĦTEK was a cross-sectional study that will effectively act like a snapshot in time.

The study population included a randomised sample of adults that had been living in Malta for at least six months and held a permanent Maltese identification card, irrelevant of their country of origin.

How is your health?

The survey took place between November 2014 and November 2015, and involved 4,000 people (18 to 70 years of age) who were statistically chosen from the national registry. We set up examination hubs in each town where the participants came in to complete socio-demographic questionnaires. While participants were there, we also took several measurements, including blood pressure, weight, height, and waist circumference. Finally, we took blood samples to check for their glucose levels during fasting periods, genetic analysis, and lipid profile (cholesterol and fats in the blood).

In the end, 47.15% of the invited adults actually attended the health survey. From these, we found that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 10.39%, with males being more affected than females. From the total T2DM group, 6.31% were known diabetics, while the remaining 4.08% were newly diagnosed with T2DM during the study. The numbers mean that over the past couple of decades there has been a rise in the diabetes rate in adults. Higher levels of T2DM mean that related diseases, such as obesity and heart problems, will also be more common.

In fact, study participants were often overweight (35.66%) or obese (34.11%). The weight increase is very relevant because it puts pressure on the body’s organs, including the pancreas, which has a direct link to T2DM development.

An increase in weight increases waist size, and this too comes with its own set of problems called the metabolic syndrome—increased blood pressure being one of many. A third of survey participants reported a high blood pressure (30.12%), again with a male majority.

Tobacco smoking was also prevalent at 24.3% (male majority). Smoking is linked to T2DM development, increased blood pressure, and stroke.

What are the implications?

The survey results are a major public health concern. An unhealthier population means higher demands on Malta’s healthcare services.

In 2016 diabetes cost Malta an estimated €29 million, while obesity cost an estimated €24 million. The increased disease rate identified means that Malta’s bills are set to rise.

Men seem to have a worse health profile than women. Older males with a high body mass index (BMI) were more likely to suffer from high blood pressure. The majority had normal levels of glucose but abnormal lipid profiles, so even though the sugar levels were normal, they were still at risk when it came to acquiring diseases such as heart problems. Those diagnosed with a metabolic syndrome were five-fold more likely to also have T2DM. There is no denying—the gender gap is a concern.

The survey shows that more public health research is in dire demand. Malta’s underlying problem appears to be the increasing overweight-obesity problem. A number of initiatives have already been put in place by the Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Directorate as well as the establishment of “Dar Kenn Għal Saħħtek”, but there is more to be done.

Gender sensitive action is needed. Government, private entities, communities, and NGOs all need to work together to change the harmful lifestyle choices that have become the norm today. Sedentary lifestyles need to change and high intakes of fat, sugar, and salt need to decrease to alleviate Malta’s weight and diabetes problem. A diabetes screening programme also needs to be introduced to help citizens help themselves.

Early diagnosis of this disease will benefit all of Malta’s health and wellbeing and safeguard its health services. What more could we hope for?

Read more:

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., Pace, N., & Mamo, J. (2016). Diabetes, pre-diabetes and their risk factors in Malta: A study profile of national cross-sectional prevalence study. Global Health, Epidemiology and Genomics, 1. https://doi.org/10.1017/gheg.2016.18

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., et al. (2016). The diabesity health economic crisis-the size of the crisis in a European island state following a cross-sectional study. Arch Public Health; 74: 52.

Cuschieri, S., Vassallo, J., Calleja, N., et al. (2016). Prevalence of obesity in Malta. Obes Sci Pract 2016; 2: 466–470.

Busting out of the box

Aesthetic physician and artistic consultant Dr Joanna Delia traces her journey from medical student to successful business owner, telling Teodor Reljić that her experience at the University of Malta helped her resist excessive industry specialisation.

Modern life is rigidly compartmentalised. Perhaps this is more true of the West than anywhere else, where the materialist, rationalist models that have aided efficiency and technological advancement also require us to absorb vast amounts of knowledge early on, and specialise later.

Many educational systems reflect this tendency and the Maltese model is no exception. From a very young age, exams come in thick and fast, and cramming to pass them replaces a more holistic education.

Dr Joanna Delia is not a fan of the word ‘holistic’—preferring the term ‘polyhedral’ for reasons that will be explained later—and has enjoyed a career trajectory that has flouted excessive specialisation. A doctor turned aesthetic physician with an interest in the world of contemporary art, Delia’s journey is an affront to such restrictive notions.

While she assures me that her own time at the University of Malta (UM) was nothing short of amazing, in recounting the roots of her intellectual curiosity, she is compelled to go even further back.

‘Like every excited little girl, my dreams used to alternate and metamorph somewhere between wanting to be a writer like Emily Brontë or Virginia Woolf and a scientist who would make incredible discoveries and change the world like Marie Curie,’ Delia recalls. ‘I also wanted to be a doctor who would cure people in war-torn countries, yet fantasised about being Alma Mahler or a young Chanel surrounded by philosophers, drenched in fine clothes and surrounded by white rose bouquets…’

Delia recounts this awareness that we’re shaped to view these inclinations as contradictory. But for her, the intuitive desire to learn about and closely observe scientific phenomena matched the heights of aesthetic appreciation.

Vella’s own student enthusiasm did not come as immediately as all that, however. While she is now secure in her three-pronged role as writer, performer, and translator (also acknowledging her former role as a lecturer), forging an early path as a student meant first squinting through the fog.

‘I just loved learning the science subjects… figuring out protein synthesis and DNA replication literally made me feel giddy, light headed, downright euphoric! I was a real geek,’ Delia says with disarming self-deprecation. ‘To me, it was just the same as reading an incredible work of literature or staring at a work of contemporary art alone in one of the silent, perfectly lit halls of a museum.’

Given this internal push-pull across various disciplines, Delia confesses that in terms of pursuing the later strands of her formal education, she ‘floated into medical school’ without feeling the need to strategise things much further. It was only upon graduation that the realities of being slotted into a specialised discipline dawned on her with an ominous pall.

‘The day I graduated I felt a suffocating feeling: the thought that I had somehow sealed my fate,’ Delia says, though the sense of regret which followed did not linger for much longer.

‘Looking at one’s future through a tunnel vision perspective based on the imaginary restrictions of one’s degree is just that a self-imposed illusion,’ Delia observes.

Her University years were active and inspiring, with Delia having happily taken on extra-curricular activities and also quietly rebelled against the notion of boxed-in specialised disciplines.

University and beyond

‘University was amazing! I would repeat those years ten times over,’ Delia unapologetically enthuses. Though she does acknowledge that the Medicine course was challenging to begin with—citing the ‘competition among students’ as an additional factor—she looks back on both her time there, and her association with the UM’s Medical School, with immense pride.

‘My lecturers were charismatic and experts in their field, which of course garners respect and made us feel honoured to be part of that system,’ Delia says, while also recalling her involvement in additional campus activities.

‘I was the chair of the environmental committee at KSU and served two terms as the Officer for the Sub-Committee on Refugees and Peace within MMSA. I loved my time on campus, and encourage all students to participate in campus affairs. We never stopped organising fairs, events, fundraisers, workshops, and outreach programmes with the community…’

Hinting at an essential discomfort with the idea of overbearing specialisation, Delia believes ‘the Maltese education system does not proactively encourage sharing knowledge’, but also notes that she did find hope, solidarity, and inspiration among her peers, from various faculties.’ I socialised with students from the architecture department, and attended their workshop parties. I was invited to history of art lectures and tours. I organised panel discussions to reduce car [use] on campus and lobby for [a] paperless [campus],’ Delia says. All these activities contributed to ‘a feeling of a hopeful future’.

Adjacent to Delia’s academic efforts were her course-related travels abroad, which contributed to expanding her horizons. ‘I did internships in Rio De Janeiro and travelled to India and Nepal through the Malta Medical Students’ Association (MMSA), both of which were incredible experiences.’ During this time, she gained a keener interest in art.

‘My sister was studying history of art and eventually read for a Ph.D. in Museology. I followed her as closely as I could; her subjects fascinated me and a lot of her excitement about art rubbed off on me…’

But first, her early medical career needed seeing to. Delia admits that medical students in Malta are somewhat privileged since they enjoy a relatively smooth changeover from academic to professional life. However, the change happens very rapidly.

‘Young doctors in Malta have the advantage of an almost flawless transition into a job. This also turns out to be the toughest time in your life, but at least there there is a continuity of support at the start of your profession,’ Delia says, citing the diligence and discipline instilled into her and her peers by their University tutors and lecturers. This rigour was crucial to ensure that those early years went on as smoothly as possible.

Pausing to reflect, Delia feels compelled to add that a culture that leaves more breathing room for exploration and enquiry could only be beneficial for the future of Maltese medicine. ‘I wish we had a stronger culture of research and publication in Malta. We need to somehow find time for it as it will not only improve the reputation of the institution but also nurture us as students, alumni, and professionals, and keep us on our toes,’ Delia says, adding that these ideas reflect the same culture of hard work that her course promoted, which rewards diligence and depth. ‘I believe in constantly keeping astride with knowledge by reading publications and actively pursuing ‘continued medical education’. I wish that the institution instilled more of this into its alumni,’ Delia muses.

This approach of constant enquiry arguably gave Delia a fount of knowledge and inspiration to draw from when she found herself at a forking road in her medical career.

Expanding horizons

”After a few years of working at the general hospital, I was lucky enough to be chosen to pursue some level of surgical training, but by that point I had realised that the life of a surgeon was not for me…’

This was an ‘extremely tough decision’, with regret once again raising its ugly head. ‘However, the 80-hour weeks, and above all the realisation that my professional life would be all about facing and treating ill and dying people, forced me to make a decision to leave the hospital,’ Delia says.

This pushed Delia to explore other careers, and she now juggles her love of both medicine and aesthetics in a sustainable way.

‘After I stopped working as a hospital doctor, there were too many things I was hungry to explore – one of them was medical aesthetics. I started pursuing training in London and Paris, and essentially spent years of salary training with the best doctors I could find.’

After working at a reputable local clinic, Delia finally managed to go at it independently, opening up her own place.

‘It was nothing short of a dream come true. I had to search hard within myself and build up entrepreneurial and management skills. I learnt the hard way sometimes, business-wise, but I was also fortunate to find help from my friends who excel in other fields like marketing, photography and architecture, to help me build my brand and clinic,’ Delia recalls.

In the end, her resistance to rigid specialisation helped her to open a thriving business called Med-Aesthetic Clinic People & Skin. She couples this work to her position as head of the Advisory Board at the newly-opened Valletta Contemporary, a boutique showcase for local and international contemporary art run by artist and architect Norbert Francis Attard.

Which brings her story back to a ‘polyhedral’ conception of the world.

‘I believe everything in life is polyhedral. I prefer polyhedral to ‘holistic’. Every square, or rather, every cube we think we’re trapped in, can be pushed out and reconfigured to welcome other disciplines. I don’t believe any of us purposely split the two fields, but I believe we don’t allocate enough time to explore all the wonders we could discover if we used both their lenses to analyse the world. After all, even Einstein believed that the most important thing in science is creativity…’

A healing touch

Emerging research suggests that mild sensory stimulation like touch can protect the brain if delivered within the first two hours following a stroke. Laura Bonnici speaks with experimental stroke specialist Prof. Mario Valentino to find out how uncovering the secrets of this ‘touch’ may have life-changing implications for stroke patients worldwide.

Stroke is universally devastating. Often hitting like a bolt from the blue, it is the world’s third leading cause of death. In Malta, over 10% of the deaths recorded in 2011 were due to stroke. But stroke inflicts suffering not only through a loved one’s passing. As the most common cause of severe disability, stroke can instantly rob a person of their independence and dignity—even their very personality. This impact, individually, socially, and globally, makes stroke research a top priority.

Yet while scientists know the risk factors, signs, symptoms, and causes of both main types of stroke—whether ischemic, in which clots stop blood flow to the brain, or haemorrhagic, where blood leaks into the brain tissue from ruptured vessels—they have yet to find a concrete solution.

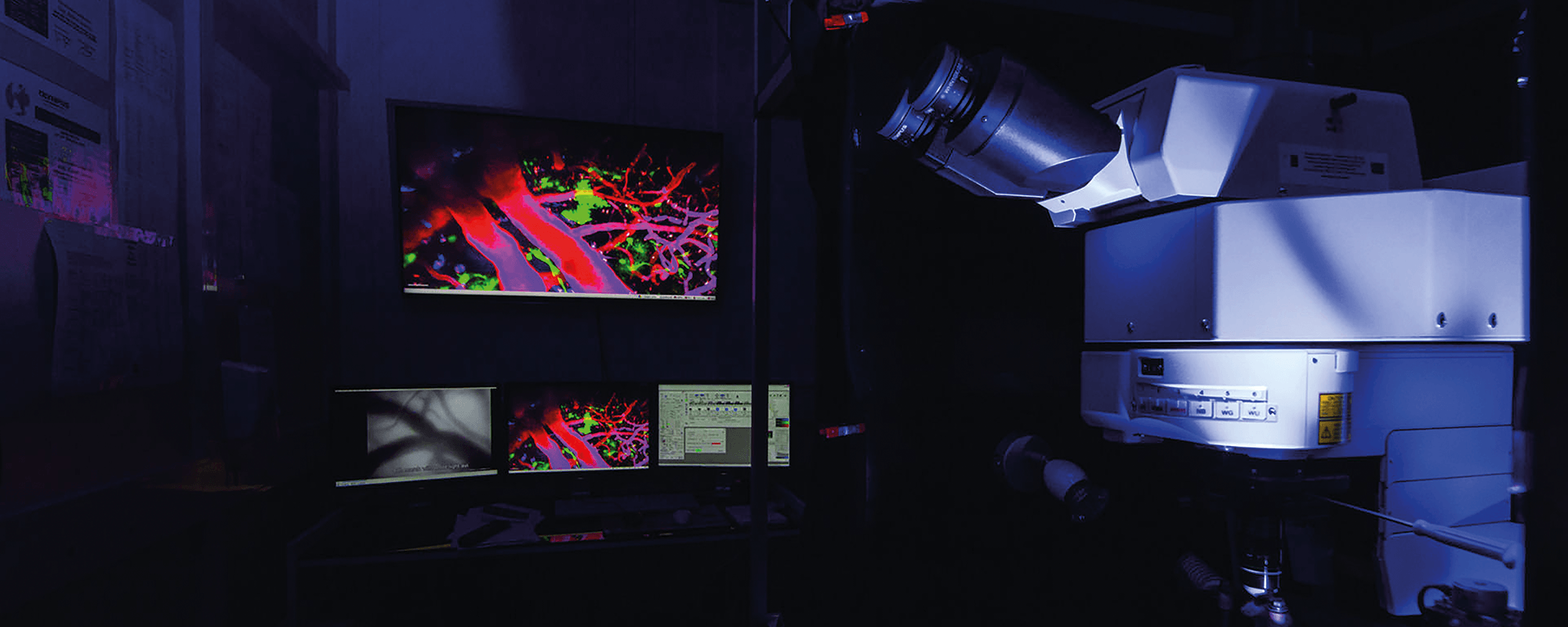

A dedicated team at the Faculty of Medicine (University of Malta) hopes to change that. Using highly sophisticated technology and advanced microscopic laser imaging techniques, Dr Jasmine Vella and Dr Christian Zammit, led by Prof. Mario Valentino, can follow what happens in a rodent’s brain as a stroke unfolds in real-time.

‘We use powerful lasers and very sensitive detectors coupled with special lenses, which allow us to capture the very fast events that unravel when a blood clot interrupts the blood supply in the brain,’ explains Valentino. ‘We observe what happens to the neighbouring blood vessels, nerve cells, and support cells, and the limb movements of the rodent throughout.’ Their aim is to find out how sensory stimulation might then help protect the brain.

The idea stems from an accidental discovery in 2010 by members of the Frostig Group at the University of Irvine, USA. The scientists found that when the whiskers of a rodent were stimulated within a critical time window following a stroke, its brain protected itself by permanently bypassing the blocked major artery that commonly causes stroke in humans. The brain’s cortical area is capable of extensive blood flow reorganisation when damaged, which can be brought about by sensory stimulation.

The human brain can bypass damage. For example, blind individuals have limited use of their visual cortex, so the auditory and somatosensory cortex expands, giving them heightened sensitivity to hearing and touch. For stroke patients, this means that the brain can compensate for its loss of function by boosting undamaged regions in response to light, touch, or sound stimulation.

‘This accidental discovery could be life-changing for stroke patients. The key is to figure out the mechanism involved in how sensory stimulation affects stroke patients, and then establish the best ways to activate that mechanism. Perhaps touching a stroke victim’s hands and face could have a similar beneficial effect, and this is what this latest research study hopes to define,’ says Valentino.

‘The team is now painstakingly correlating the data obtained during this brain imaging with the rodent’s movement and trajectory,’ he continues. ‘Using a motion-tracking device fitted under a sophisticated microscope, we can record the behaviour of the rodent during high-precision tactile stimulation, such as stroking their whiskers, and detect any gain of [brain] function through behavioural and locomotor readouts whilst ‘looking’ inside the brain in real-time.’

If they can prove that any protection is the direct cause of new blood vessels (or other cells) resulting from the electrical activity inspired by the sensory stimulation, then the next step would be to explore ways of redirecting these blood vessels to the affected brain area.

The team’s track record is encouraging. In collaboration with scientists from the University Peninsula Schools of Medicine and Dentistry, UK, they made another recent breakthrough that was published in Nature Communications, identifying a new drug, QNZ-46, that could protect the rodent brain following a stroke.

‘That project was about neuroprotective agents – to create a drug that will substantially block or reduce the injury, and so benefit a wider selection of patients,’ elaborates Valentino. ‘The study identified the source and activity of the neurotransmitter glutamate, which is the cause of the damage produced in stroke. This led to the discovery that QNZ-46 prevents some damage and protects against the toxic effects of the glutamate. This is potentially the first ever non-toxic drug that could prevent cell death during a stroke, and the results from this research could lead to pharmaceutical trials.’

While ongoing research in these projects has been supported through a €150,000 grant from The Alfred Mizzi Foundation through the RIDT, Valentino points out that globally-significant discoveries such as these are in constant need of support.

‘The funding of such projects is so important. This money is life-changing for people in such a predicament. Health research changes everything—our lifestyle, our quality of life, our longevity. And yet, government funding for research is still lacking. It’s only thanks to private companies and the RIDT, who realise the global potential of our work, that these projects can continue to try to change the lives of people all over the world,’ says Valentino.

And while Malta may be a small country with limited resources, the work conducted within its shores is reaching millions globally, proving that when it comes to knowledge, every contribution counts. We must continue striving for more to leave our best mark on the world.

Help us fund more projects like this, as well as research in all the faculties, by donating to RIDT.

Link: researchtrustmalta.eu/support-research/?#donations

Crafting business from hobbies: The HUSKIE story

Put a physicist and an engineer together and what do you get? A brewery. Obviously. Cassi Camilleri sits down with Jean Bickle and Miguel Camilleri to talk about entrepreneurship, beer, and how variety really is the spice of life.

As you read this, a warehouse in a Qrendi quarry is bustling, undergoing hefty conversions as it morphs into a dream brewery. Water and electricity supply is solid, the walls have a fresh lap of white and the steel housings are in place. Now, the countdown begins until the tanks are set up. But they’re used to it. This waiting business.

The Huskie Craft Beer company was but a twinkle in their eye when Jean Bickle and Miguel Camilleri first met as workmates during a stint in Leeds, which is where they discovered a thriving craft beer scene.

‘We were part of a club at the Wharf Chambers,’ Bickle remembers. ‘It’s what we did after work. We played table soccer and tried beers.’ Learning about the process, the recipes, and the different flavours that are possible to incorporate in a beer, planted a seed in them both. ‘Eventually, when we came back home, we wanted to give brewing a shot ourselves,’ Bickle adds. And so they did.

Getting the basics down

Their first investment was in education. ‘We spent quite a bit on books and materials to learn how to brew,’ Jean says. They had the ingredients down—water, malt, yeast, and hops. Hops being the flowers of the hop plant which are used as a bittering, flavouring, and stability agent in beer. They understood the role temperature played and gained plenty of experience with identifying flavours through taste tests. Beyond this, however, they also needed to be familiar with how these ingredients interact with one another and the techniques involved in creating a beer.

They were more careful with their purse strings when building their first set up in early 2017. ‘We could have very easily gone online and found these home brewing kits. But you have to spend a lot of money to get those. And this was all coming from our own pockets. So, with Miguel being an engineer, we just bought stainless steel tanks and sheets, shaped them, and welded the parts together. We even built the control panel and electronics ourselves. Everything was done from scratch.’

This is not to say that it was all smooth sailing. ‘Sometimes you get ahead of yourself. You start rushing in your eagerness to try out new things. Which is fine. But sometimes you have to take a step back and go back to basics. We keep each other in check,’ Jean notes, smiling. ‘We both come up with radical ideas on how to approach the task at hand, but you can’t do everything at once, otherwise you get careless.’

‘You’ve also got to be adaptable and not follow others’ rules to the dot. Malta’s ambient conditions and accessible raw materials make brewing harder than in many other countries. With the right technique though, it’s definitely possible,’ Miguel points out.

Creative thinking meets business

Initially, it was all about making beer. ‘Our focus was that the quality of the process should be done to a certain standard,’ Jean says, but the creative element soon started becoming a priority. ‘Now we have shifted to the actual product being top quality. You have loads of recipes online if you want to find them, but we wanted to create our own.’

From a business standpoint, finding what makes you unique is an essential part of building a company. What is the value you are bringing to your client base that others are not?

Huskie’s approach harkens back to the reason the boys started the company. They loved beers and wanted to continuously try new ones. When they had the brewing process perfected, it was time to start being experimental.

‘We started thinking about creating recipes we hadn’t seen before, with flavours we hadn’t seen anyone use before. We made beers using Maltese strawberries for example, and we also produced a range of beers inspired by the flavours of the traditional qagħaq ta’ l-għasel (honeyring).’ Of course this isn’t as simple as adding some extra water to a cake mix.

‘Experimentation brings about its own set of challenges. Some ingredients have their own sugars, so including them in the beer recipe drives the yeast crazy.’ And when Jean says crazy, he means it. ‘If we don’t get everything right, the pressure in the bottle can build up and they literally explode. We’ve had this happen a few times,’ Jean admits. ‘We call them molotovs,’ Miguel grins.

But even with the added cleaning time, all’s well that ends well. This curiosity has given Huskie a very niche service they can provide to clients. ‘We can create beers exclusive to our clients. If someone comes along and tells me I like cinnamon or whatever, we can create something specifically for them.’

Coming up with each new recipe involves another process of trial and error, tinkering, and perfecting. ‘When we come up with a new recipe, we usually come up with three different versions and we taste each different beer on the same day. We write down notes, we compare, and if there is some kind of consensus, we move onto that.’ Now, Jean and Miguel have a spreadsheet with all the beers they produce, each marked with a rank. So far, over the course of two years, they’ve already finalised 11 beer recipes and released four to the market!

No to mass markets

The culture behind craft beer is one that is very close to Jean and Miguel’s hearts. This is not about making three beers, sticking to them, and selling them en masse. They want to keep the personal touch, the Maltese identity in their product, while pushing boundaries and trying new things. ‘So our philosophy is get this beer now because it won’t be around in six months. We want to continue creating.’

Of course, this isn’t always easy. And Jean is the first to say it. ‘It’s hard letting go of a good beer,’ he admits. ‘Even we fall in love with some of the recipes. But you have to come from a place of abundance. We know we can continue to create good beers. And we will.’

Now they’re in the growing phase. Setting themselves up to expand their brewing power. With the new brewery they’ll soon be able to increase production tenfold. ‘Then it’s about creating our own events. Entering competitions abroad. We want to put Malta on the map.’

‘We’ve already spent a year working on the new brewery, so we’ve had a lot of time to think about what we want to do and where we want to go, and this is essential in building a business that is sustainable. You have to do things right and really think about things properly,’ Miguel asserts.

This measured attitude has definitely worked in Huskie’s favour. Research led to new funding opportunities. ‘Miguel found out about [the] TAKEOFF [business incubator] and we met Joe Bartolo. He really motivated us and was of great help in the vital early stages,’ Jean says. After a few months Huskie was awarded a TOSFA fund that they used to purchase more equipment, allowing them to try more recipes and scale up production. They followed this up with some EU funding applications. ‘We [obtained] funding to purchase more equipment for the brewery,’ he notes.

Jean is quick to mention the help and support from their family and friends.

‘We got a lot of help. Really a lot. Miguel’s father helped us with the building of the brewery. His uncle did all the electricity. And Connie, Miguel’s mum is a star. Miguel did all the planning, plumbing, and the majority of the rest. He’s even got the scars to prove it! I painted a wall. It was a real team effort,’ Jean laughs.

Maintaining Balance

For such a new business, Huskie is already growing with leaps and bounds. But hours in the day are limited and questions about priorities and goals are already circling. ‘Managing Huskie at its current level already takes up loads of our time, and we’ve had to sacrifice a lot from our private lives,’ Jean says. ‘But in doing that, Miguel and I manage to run it whilst still holding full time positions. Where it will take us in the future—well, who knows? We wouldn’t mind employing people to take care of logistics and cleaning for example. We’re also looking into hiring a driver to take care of distribution for us.’

The love they have for medical physics has in no way diminished. ‘Miguel and I both love what we do. Working in healthcare is extremely satisfying and keeps us well in check on life’s priorities,’ Jean says. ‘And that is just as much our passion as brewing beer is. But I believe that if you work hard enough at something, and if you love it enough, you’ll find the time for it.’

‘Everybody will say you’ll enjoy it once you get there. But for us it’s more important to enjoy what we’re doing while getting there. God forbid Miguel and I weren’t friends. We’d kill each other with all the time we spend in the same room. For us, the brewing thing works because it’s part of the development of our friendship. We brew, drink, chat, and joke. It’s about enjoying the process. Not just tunnel vision towards the end goal.

Science and coffee, anyone?

In an age of misinformation, having a grasp on current affairs and research is essential for us to be active, responsible citizens. Gillianne Saliba writes about the dire need for more dialogue and engagement from citizens and scientists alike.

For many, science is far removed. It’s just a subject they had to take at school. Or the star of crazy stories on newspapers, or videos and memes on social media. Opposing views are a dime a dozen. And sometimes it’s very hard to discern between them; what’s right? what’s wrong? ‘It’s complicated,’ they say, ‘it’s hard’, and so most people move on, letting others do all the talking. As a result, science and citizens have had a rocky relationship. But when the issues being discussed relate to health, technology, and our environment, that is, when they affect us directly, we need to be able to engage.

Science Communication (SciComm for short) can offer a solution to this problem.

SciComm can take many forms. Articles, films, museum exhibitions; you name it. In the wake of a scientific knowledge-gap in the community, SciComm has taken root and has been rapidly growing over the last 40 years. Researchers want to share their ideas and get citizens’ input, gauge interest, and see what others have to say.

Enter Malta Café Scientifique.

To create a safe space where people can chat about science, Malta Café Sci organises monthly science communication events in Valletta where researchers and professionals discuss topics of interest with attendees. Entrance is completely free and open to all, which attracts a diverse audience.

What makes Malta Café Sci special is how it prioritises the public, putting their learning experience first. The events are tailored to them. Speakers keep their talks short and succinct, taking complex scientific concepts and breaking them down, discussing how the research can impact society. The Q&A session that follows is often far longer than the talk itself, opening up a dialogue within the audience. The elitist mantra of ‘it’s complicated’ is so far gone that talks, and the following question and answer portion of the evening, are put to bed with closing drinks where speakers and audience members can have one-on-one time, discussing the topic of the day.

I have been volunteering as an organiser with Malta Café Scientifique for the last nine months. Through the experience, I have gained marketing and public speaking skills.

More importantly, I have had the privilege of a front row seat to pivotal moments in people’s lives—the moment when perception shifts.

I’ve often had audience members come up to me after an event to tell me how the talk changed their ideas. How they are learning to be more receptive but also critical about what they learn and read online. Some point out how they usually steer clear of such events, with many wrongly thinking they aren’t smart enough for them, only to find that they not only understand, but can also participate.

Aside from all this, Malta Café Scientifique is also conducting its own research. Led by Café Sci’s project manager Danielle Martine Farrugia, we are evaluating and interviewing different science communicators about their practices. We’re also evaluating the initiative to understand its contribution to science communication in Malta.

What we can already see is that Malta Café Sci is living, breathing proof of how people can come together when dialogue is open and welcoming. It is empowering local researchers to share their findings with citizens while giving community members the chance to learn and weigh in on work that may have ramifications for them. Where a learning process is no longer from expert to layman, but a continuous sharing of information in both directions.

Note: For more about Malta Café Scientifique’s next events, or if you want to get involved, see its Facebook page or Instagram @maltacafesci. Or email us on cafesci@mcs.org.mt.

Enter the swarm

Author: Jean Luc Farrugia

Once upon a time, the term ‘robot’ conjured up images of futuristic machines from the realm of science fiction. However, we can find the roots of automation much closer to home.

Nature is the great teacher. In the early days, when Artificial Intelligence was driven by symbolic AI (whereby entities in an environment are represented by symbols which are processed by mathematical and logical rules to make decisions on what actions to take), Australian entrepreneur and roboticist Rodney Brooks looked to animals for inspiration. There, he observed highly intelligent behaviours; take lionesses’ ability to coordinate and hunt down prey, or elephants’ skill in navigating vast lands using their senses. These creatures needed no maps, no mathematical models, and yet left even the best robots in the dust.

This gave rise to a slew of biologically-inspired approaches. Successful applications include domestic robot vacuums and space exploration rovers.

Swarm Robotics is an approach that extends this concept by taking a cue from collaborative behaviours used by animals like ants or bees, all while harnessing the emerging IoT (Internet of Things) trend that allows technology to communicate.

Supervised by Prof. Ing. Simon G. Fabri, I designed a system that enabled a group of robots to intelligently arrange themselves into different patterns while in motion, just like a herd of elephants, a flock of birds, or even a group of dancers!

I built and tested my system using real robots, which had to transport a box to target destinations chosen by the user. Unlike previous work, the algorithms I developed are not restricted by formation shape. My robots can change shape on the fly, allowing them to adapt to the task at hand. The system is quite simple and easy to use.

The group consisted of three robots designed using inexpensive off-the-shelf components. Simulations confirmed that it could be used for larger groups. The robots could push, grasp, and cage objects to move them from point A to B. To cage an object the robots move around it to bind it, then move together to push it around. Caging proved to be the strongest method, delivering the object even when a robot became immobilised, though grasping delivered more accurate results.

Collective transportation can have a great impact on the world’s economy. From the construction and manufacturing industries, to container terminal operations, robots can replace humans to protect them from the dangerous scenarios many workers face on a daily basis.

This research project was carried out as part of the M.Sc. in Engineering (Electrical) programme at the Faculty of Engineering. A paper entitled “Swarm Robotics for Object Transportation” was published at the UKACCControl 2018 conference, available on IEEE Xplore digital library.