In early modern Malta, some men resisted patriarchal attitudes which oppressed women. Drawing upon two cases lifted from primary sources, Dr Christine Muscat argues that written history has largely neglected the voices of men who manoeuvred patriarchal structures to empower women.

Eighteenth-century Malta was a dynamic, adaptive place. In the hinterland farmers struggled to transform barren areas into productive land. In the harbour district, on the Eastern side of the island, people from all walks of life wove their way into a multi-coloured, multi-faceted cultural tapestry. The establishment of the Hospitaller convent in 1530 transformed the once desolate Marsa into a landscape of opportunities.

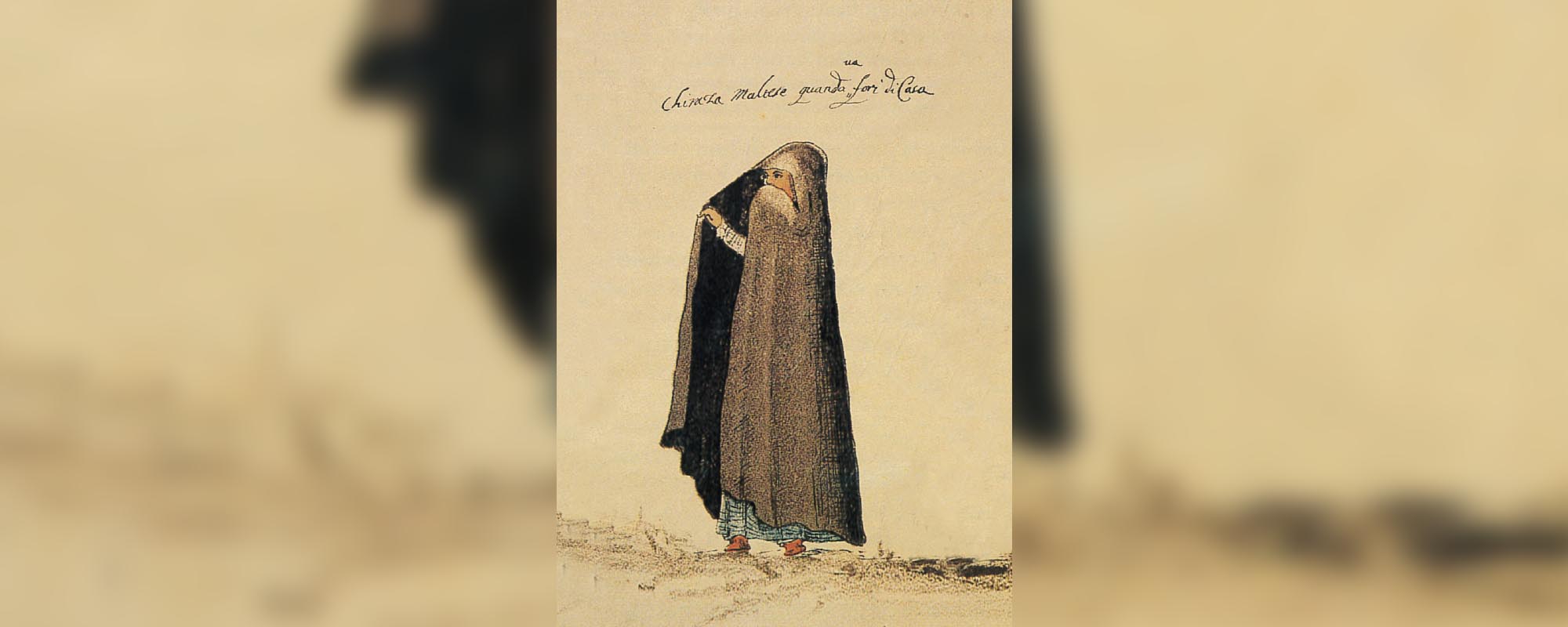

Still, hierarchical class relations based on economic differentiation and social stratification continued to define the social reality of the island’s denizens. An overarching patriarchal Catholic morality maintained a tight grip on society — most oppressively on women, who were economically disadvantaged, excluded from public life, and subordinate to family interests. Women were not necessarily passive to the strictures and structures that controlled them. Trials lifted from the Bishop’s court and the secular court show that some women resisted or negotiated oppressive configurations, and some men appear to have helped women to act independently.

Female prostitute entrepreneurs

Monographs on women’s histories in Malta started late in the early 21st century. Women are mentioned in Attilio Critien’s 1949 study on foundlings under the Hospitallers and in Paul Cassar’s 1964 book, Medical History of Malta. Cultural perspectives on women in Hospitaller Malta emerge in Frans Ciappara’s 1988 monograph on marriage in late eighteenth-century Malta and his subsequent Society and the Inquisition in Early Modern Malta, published in 2000. Sporadic essays were also published on the deeds and misdeeds of early modern women in Malta. Carmel Cassar’s Daughters of Eve (2002) is the first published socio-cultural study on early modern women in Malta. Carmel Cassar showed how women in the 16th and 17th centuries overcame or ignored confining norms imposed on them.

My monograph, Public Women: Prostitute Entrepreneurs in Valletta 1630–1798, published in 2018, is a study that looks into the entrepreneurial pursuits of some early modern prostitutes in Valletta. It provides evidence of women carving out individual spheres of autonomous action by making choices, employing wealth, and influencing men as well as other women. At first glance this may not seem phenomenal, but the fact that these women operated in a city of chaste men made their achievements conspicuous.

The question of whether men aided women in their lives was peripherally approached in Emanuel Buttigieg’s pioneering book Nobility, Faith and Masculinity: The Hospitaller Knights of Malta, c.1580-c.1700 (2011). The Knights’ vocational mission included charity. Charitable deeds bestowed on women did not always sit comfortably with religious austerity and patriarchy.

[My book] provides evidence of women carving out individual spheres of autonomous action by making choices, employing wealth, and influencing men as well as other women.

Feminist historians like Margaret F. Rosenthal and Liz Sperling associate male motivations to help women navigate patriarchal authority to political or sexual intentions, or chivalry. In his study on patrician society in Renaissance Venice, Stanley Chojnacki gives alternative motivations: respect, solicitude, and affection. Functioning on an unconscious level, a number of Maltese Baroque novels, like Giammaria Ovvero L’ultimo dei Baroni Cassia and Frà Fabrizio Cagliola’s Disavventure Marinaresche, offer rich evidence of these ideologies. A sense of righteousness may have been an ulterior motivation that drove some men to support women.

From Jesuits to seamen

In May 1703, Father Emanuel Sanz, a Jesuit residing in the Collegium Melitense in Valletta, was called to testify in the Bishop’s Court. He was questioned on the mannerisms of Ursula Gatt, an alleged prostitute, who passed away on 26 February 1702. His deposition formed part of a long-drawn out litigation between the Magdalene Nuns and Gatt’s relatives over death dues. Following the good counsel of the erudite Don Girolamo Bisano, Sanz recounted having informed Ursula that she could, in all good conscience, abstain from cohabitating with her abusive husband Marcello Gatt. Sanz made it a point to emphasise that Bisano was the moral theologian and casuist of the Collegium, a reader of the sacred canons and qualifier of the Holy Office in Palermo (National Library Manuscript 1067, f.85v). In Catholic doctrine wives were duty bound to submit to their husbands. Sanz and Bisano were religious men who sanctioned a married woman’s abandonment of her husband. They supported Ursula Gatt’s interests without ‘religious’ or ‘patriarchal’ qualms. In another case dating to 30 January 1740, frustrated by judicial inefficiency and procrastination, Onorato Zolan filed an urgent appeal in the Magna Curia Castellania, the secular tribunal of the Order of St John (1530-1798). Zolan was a seaman who was about to embark on a journey.

The job was important; he urgently needed money to support his family. He informed the Court that a warrant of impediment of departure had been issued against him by Captain Claudio Castagnè in security of an ongoing Court dispute. Clearance was subject to the defendant’s constitution of a procurator litis – a person legally appointed to represent someone else in court litigation. Castagnè’s demand was illegitimate. On 27 January 1740, Zolan had given his wife Margarita power to act in his name. The deed was drawn by Notary Gio Andrea Abela. Zolan attributed the judiciary’s delay to the fact that his procurator was female. The plaintiff was cited as a possible conspirator. Zolan insisted that women had every right to act as procurators (come se fosse proibito dalle Leggi, che le Donne potessero essere constituiti Procuratrici). Denying such rights was utterly absurd and ‘an open calumny’ (essendo ciò un assurdo, et una aperta calunnia) (National Archives of Malta, Court Proceedings Box 406: Supplica Onorato Zolan). A ‘calumny’ is a false and malicious statement designed to harm someone. The word ‘open’ makes the injury infinite. Powerful words.

They supported Ursula Gatt’s interests without ‘religious’ or ‘patriarchal’ qualms.

Sanz, Bisano, and Zolan’s voices surfaced during my research on public women. There are many other male voices waiting to be heard. These are voices that show that there were righteous men who were not impassive to the patriarchal conventions and institutions which unjustly penalised women. In January 1740, patriarchal ideals, lack of preparation, late preparation or incompetency may have inhibited Judge Pietro de Franchis from responding positively to Zolan’s appeal. My experience in studying women’s history in Malta and Western Europe shows that the same shortcomings, this time under the umbrella of a feminist critical edge, may be obstructing modern historians from engaging with the past with an open mind.

‘As he that binds a stone in a sling,

So is he that gives honour to a fool’ (Proverbs of Solomon 26:8)

Further reading:

Muscat, Christine, Public Women: Prostitute Entrepreneurs in Valletta 1630-1798 (Malta, BDL Publishers, 2018).

Muscat, Christine, ‘Regulating Prostitution in Hospitaller Malta the Bonus Paterfamilias Way’ in Storja (2019).

Buttigieg, Emanuel, Nobility, Faith and Masculinity: The Hospitaller Knights of Malta, c.1580-c.1700 (London & New York, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2011).

Comments are closed for this article!