Translation is both a science and an art with practical applications. Let’s explore how translation can address cultural and linguistic misunderstandings in the tourism industry.

Continue readingA career fashioned in Malta

Heidi Ruggier wanted to study film. Today she’s president and founder of Toronto-based public relations company Matte PR, advisor with Ryerson University’s School of Fashion programme, and mentor with Toronto Fashion Incubator. In her world, that’s a perfectly logical outcome. Words by Cassi Camilleri.

Continue readingThe language of <3

Can emojis replace words, or are they pretty decorations to our verbal communication? Latasha Barbara looks into the science behind our use of emojis.

Continue readingScience and coffee, anyone?

In an age of misinformation, having a grasp on current affairs and research is essential for us to be active, responsible citizens. Gillianne Saliba writes about the dire need for more dialogue and engagement from citizens and scientists alike.

For many, science is far removed. It’s just a subject they had to take at school. Or the star of crazy stories on newspapers, or videos and memes on social media. Opposing views are a dime a dozen. And sometimes it’s very hard to discern between them; what’s right? what’s wrong? ‘It’s complicated,’ they say, ‘it’s hard’, and so most people move on, letting others do all the talking. As a result, science and citizens have had a rocky relationship. But when the issues being discussed relate to health, technology, and our environment, that is, when they affect us directly, we need to be able to engage.

Science Communication (SciComm for short) can offer a solution to this problem.

SciComm can take many forms. Articles, films, museum exhibitions; you name it. In the wake of a scientific knowledge-gap in the community, SciComm has taken root and has been rapidly growing over the last 40 years. Researchers want to share their ideas and get citizens’ input, gauge interest, and see what others have to say.

Enter Malta Café Scientifique.

To create a safe space where people can chat about science, Malta Café Sci organises monthly science communication events in Valletta where researchers and professionals discuss topics of interest with attendees. Entrance is completely free and open to all, which attracts a diverse audience.

What makes Malta Café Sci special is how it prioritises the public, putting their learning experience first. The events are tailored to them. Speakers keep their talks short and succinct, taking complex scientific concepts and breaking them down, discussing how the research can impact society. The Q&A session that follows is often far longer than the talk itself, opening up a dialogue within the audience. The elitist mantra of ‘it’s complicated’ is so far gone that talks, and the following question and answer portion of the evening, are put to bed with closing drinks where speakers and audience members can have one-on-one time, discussing the topic of the day.

I have been volunteering as an organiser with Malta Café Scientifique for the last nine months. Through the experience, I have gained marketing and public speaking skills.

More importantly, I have had the privilege of a front row seat to pivotal moments in people’s lives—the moment when perception shifts.

I’ve often had audience members come up to me after an event to tell me how the talk changed their ideas. How they are learning to be more receptive but also critical about what they learn and read online. Some point out how they usually steer clear of such events, with many wrongly thinking they aren’t smart enough for them, only to find that they not only understand, but can also participate.

Aside from all this, Malta Café Scientifique is also conducting its own research. Led by Café Sci’s project manager Danielle Martine Farrugia, we are evaluating and interviewing different science communicators about their practices. We’re also evaluating the initiative to understand its contribution to science communication in Malta.

What we can already see is that Malta Café Sci is living, breathing proof of how people can come together when dialogue is open and welcoming. It is empowering local researchers to share their findings with citizens while giving community members the chance to learn and weigh in on work that may have ramifications for them. Where a learning process is no longer from expert to layman, but a continuous sharing of information in both directions.

Note: For more about Malta Café Scientifique’s next events, or if you want to get involved, see its Facebook page or Instagram @maltacafesci. Or email us on cafesci@mcs.org.mt.

STEM ambassadors thrashing stereotypes

Over the last four decades, STEM industries have risen to great heights. Scientific, technological, engineering, and mathematical minds have been called to rally. And the demand continues. How can you contribute?

Few would dispute that technological and scientific advancements dominate the 21st century. Adverts provide ample proof. From tablets to smartphones, to robot home appliances and driverless cars, our world is changing fast. As a result, we are now living in a global knowledge-based economy where information can be considered as the highest form of currency. This reality comes with both benefits and challenges.

Statistics from 2013’s European Company Survey show that 39% of European Union-based firms had difficulty recruiting staff with STEM skills. Malta is no exception. Another report in 2018 showed that people with STEM careers are still in short supply locally, especially in the fields of healthcare, ICT, engineering, and research. So, while the jobs are available, there aren’t enough people taking up STEM careers, and this is holding Malta back.

There are many reasons for this trend. For one, Malta has a low number of tertiary level graduates; the third lowest in the EU. An array of harmful stereotypes can also shoulder some blame. The ‘fact’ that people in math, science, and technology ‘don’t have a social life’ is unhelpful. The ‘nerd’ image is still prevalent, especially among the younger generations that are still in primary and secondary school. Then there is the ‘maleness’ associated with STEM jobs and industries. According to Eurostat statistics, in 2017, from 18 million scientists and engineers in the EU, 59% were men and 41% women.

Still, this is far from the whole picture.

Employers have reported instances where, despite having enough graduates to fill roles, applicants did not possess the right non-technical skills for the job. This was especially true for abilities such as communication, creative thinking, and conflict resolution.

Many were unprepared to work in a team, to learn on the job, and to problem solve creatively. This is a real concern, especially for the country’s future. At the rate with which markets are evolving, a decade from now young people will be applying for jobs that do not exist today, and the country needs to prepare students for these roles. And it has to start now.

The Malta Council for Science and Technology (MCST) is trying to do this through an Erasmus+ project called RAISE. They are launching an Ambassador Programme to empower young students to take up the STEM mantle. STEM Career Cafés are going to be popping up in schools all over Malta, alongside a Career Day at Esplora aimed to inform and inspire. This is where you come in.

They want undergraduates from the University of Malta and MCAST to work with Esplora by sharing your experiences in STEM and telling your stories to encourage those who may be considering a STEM career. STEM Ambassadors will gain important public engagement skills while making research and science careers more accessible.

STEM is crucial in our contemporary world; our economies depend on it. It has completely changed the way we live and opened up new prospects for a future we never imagined. For those who have already made up their mind to be a part of it, there is now the opportunity to empower others and guide them in finding their own path.

Note: To become a STEM Ambassador, email programmes@esplora.org.mt or call 2360 2218.

The MCST, the University of Malta, and the Malta College of Arts, Science and Technology have embarked on a national campaign to promote STEM Engagement. Its first activity was a National STEM Engagement Conference.

Musical messaging: Politics in Maltese music

Music has been used as a vehicle for political commentary since time immemorial. Cassi Camilleri, Dr Mario Thomas Vassallo, and Brikkuni’s Mario Vella reflect upon the Maltese scene and its contribution to the discussion.

Music triggers all sorts of reactions and emotions in people. Hollywood’s multi-million dollar soundtracks are an eye-watering testament. Throughout history, music has also been used to transmit messages to the masses. Music can simultaneously act as a call to arms and a form of rebellion, depending on your perspective.

As part of his research into the relationship between music and politics, Dr Mario Thomas Vassallo points to the distinctly Maltese practice of adopting international hits to accompany political campaigns. Such adoptions have included We Take the Chance by Modern Talking, the anthem used by the Nationalist Party in 1998 after the collapse of Alfred Sant’s Labour Government, and, of course, New Tomorrow, Labour Party’s rallying call for change in 2013.

In another interview by Teodor Reljić, former radio presenter and music journalist Dr Toni Sant described the tendency of Malta’s political parties to rely on foreign songs as an unfortunate example of ‘cultural colonialism’. ‘It relates to the general Maltese idea that whatever comes from Britain, the US, Europe (take your pick) is better than what can be produced in Malta. It shows a lack of national cultural identity, unless the Maltese cultural identity is actually entrenched in its colonial past, rather than its more recent political history. And on it goes…’ Sant told Reljić.

Vassallo agrees with Sant’s reasoning, but adds that this ‘colonialism’ is not the only reason for the phenomenon.

‘In a globalised world, culture is being hybridised,’ Vassallo states. ‘You cannot tell what is local and what is foreign. Rihanna does not belong to Barbados, where she was born and raised as a kid, but to the world (and to Malta as well).’

Beyond this, Vassallo points to the commissioned music that political parties have funded over the years. These songs’ lyrics are usually interpretations of manifestos, used to get the electoral slogan to voters. ‘One of the most popular songs in this genre is Ngħidu Iva with lyrics by Joe Chircop and music by Philip Vella. This composition was the official song of the Nationalist Party during the 2003 referendum campaign for Malta to join the European Union,’ he writes in his paper.

But what of those operating outside the parties’ influences? Those who want to criticise and shed light on bad behaviour and problematic choices made by the powers that be? Among those most vociferous on the island are Brikkuni. Frontman Mario Vella explains his motivations saying, ‘As a songwriter, I feel inclined to delve into matters that affect me both on a personal level and in a wider context. Little matters whether one is apolitical or dismissive of this age-old phenomenon. Politics will, one way or another, force its way into our everyday lives. Addressing it is but a natural and obvious consequence.’

There are critics, of course. ‘I receive endearments of the ‘I hate you and your music’ variety,’ Vella notes; however, the results of this work have seen the band and its music embraced by many who see truth in the lyrics. L-Eletti’s message of contempt towards the ridiculousness embodied by those ‘elected’ (the English translation of eletti) is poignant especially when paired with the music’s fairground flavour. But loud voices often pay a price, and Vella is no different.

‘I have faced considerable censorship, but I hardly look at it as a repercussion. I tend to view it as an inevitable reaction to choices consciously made. There’s always some other way out of the hole. Even ones you dug for yourself. Unless you have a couple of kids to provide for. Then you’re screwed.’ Vella has none.

Vella and Vassallo both believe that there are limits to artistic expression. Vassallo puts an emphasis on ‘respect and autodiscipline’. In an interview with Vassallo, singer-songwriter Vince Fabri explained that, ‘if I want to criticise someone, I’d rather not offend him. I can definitely be satirical, cynical, or mocking, but I will never resort to vilification and absurdity.’ Vella, too, doesn’t see artistic limitation as a hindrance ‘as long as you’re the one setting it.’

There is an element of responsibility that comes with the ability to speak to people on a visceral level. Artists can use their skills for positive effect. In 2007, at the height of the immigration crisis in Malta, singer-songwriter Claudio Baglioni pointed to the fear artists’ influence can instil in politicians. This is why, he said, ‘we have to be close to politics, but not immersed in it. We can be like sentinels.’

There is an element of responsibility that comes with the ability to speak to people on a visceral level. Artists can use their skills for positive effect. In 2007, at the height of the immigration crisis in Malta, singer-songwriter Claudio Baglioni pointed to the fear artists’ influence can instil in politicians. This is why, he said, ‘we have to be close to politics, but not immersed in it. We can be like sentinels.’

At a time when the line between truth and lies gets increasingly blurred, perspective makes all the difference. If our sentinels can provide us with that, we’ll be all the better for it.

Maltese for all

What would you do if you were stripped of your words? If speech simply didn’t come to you? Sylvan Abela writes about MaltAAC, an Augmentative and Alternative Communication App for the Maltese Language.

Continue readingAccidental science

Do scientists need to have a clear end-goal before they dive down the research rabbit hole? Sara Cameron speaks to Dr André Xuereb about the winding journey that led to the unintended discovery of a new way to detect earthquakes.

Some of science’s greatest accomplishments were achieved when no one was looking with a purpose. When studying a petri dish of bacterial cultures, Alexander Fleming had no intention of discovering penicillin, and yet he changed the course of human history. Henri Becquerel was trying to make the most of dwindling sunlight to expose photographic plates using uranium when he stumbled upon radioactivity. A chance encounter between a chocolate bar in Percy Spencer’s pocket and the radar machine that melted it sparked the invention of the household microwave.

One would think that with this track record of coincidental breakthroughs, the field of science and research would continue to flourish by embracing curiosity and experimentation. But as interest piques and funding avenues pop up for researchers, there has been a shift in mindset.

Money changes things. And while it does allow people to work hard and answer more questions, it has also fostered expectations from stakeholders. Investors want fast results that will improve their business or product. We, the end-user, want to see our lives changed, one discovery at a ti me. We’re no longer satisfied with research for research’s sake. At least for the most part.

Quantum physicist Dr André Xuereb (Faculty of Science, University of Malta) is all too aware of this issue and its effects on scientific progress. Xuereb explains scientists’ frustration: ‘A lot of funding, in Malta and elsewhere, is dedicated to bringing mature ideas to the market, but that is the ti p of the iceberg. There is an entire innovation lifecycle that must be funded and sustained for good ideas to develop and eventually become technologies. The starting point is often an outlandish idea, and eventually, sometimes by accident, great new technologies are born,’ he says.

STARTING POINTS

Over the past few years, Xuereb has been exploring new possibilities in quantum mechanics.

The field of quantum mechanics attempts to explain the behaviour of atoms and what makes them. Its mathematical principles show that atoms and other particles can exist in states beyond what can be described by the physics of the ordinary objects that surround us. For example, quantum theorems that show objects existing in two places at once off er a scientific basis for teleportation.

Star Trek fans know exactly what we’re talking about, but for those rolling their eyes, the reality is that many things in our everyday lives wouldn’t exist without at least some understanding of quantum physics. Our computers, phones, GPS navigation, digital cameras, LED TV screens, and lasers are all products of the quantum revolution.

The starting point is often an outlandish idea, and eventually, sometimes by accident,

great new technologies are born

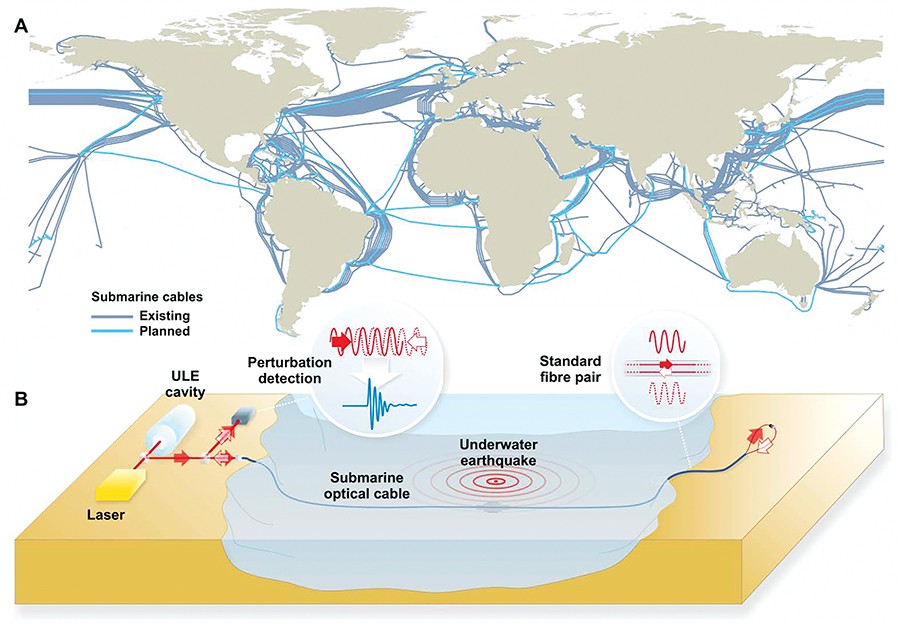

Another technology that has changed the way we live and work is modern telecommunications technology. When you pick up your phone to message a friend overseas, call a loved one, or email a colleague, telecoms networks spanning the earth carry the data across continents and under oceans through thousands of kilometres of optical fibres.

The 96-kilometre submarine telecommunication link between Malta and Sicily was Xuereb’s focus in 2015. He organised a team of European experts to begin investigating the potential for building a quantum link between the two countries.

The Austrian, Italian, and Maltese trio were particularly interested in a strange property called ‘entanglement.’ This is a curious property of quantum objects that can be created in pairs of photons, connecting them together. This entanglement can be distributed by giving one of these photons to a friend and keeping the other for yourself, establishing a quantum link between you and this friend—an invisible quantum ‘wire,’ so to speak.

Through this connection, you and your friend can send data faster than over ordinary connections; by modifying the state of the photon at your end, you can instantly affect the state of your friend’s photon, no matter how far apart you are in the universe. Using quantum links such as these, all manner of feats can be performed, including super-secure communications. ‘We wanted to demonstrate that quantum entanglement can be distributed using a 100km-long, established telecoms link, using what was already available, with no laboratory facilities in sight,’ explains Xuereb. His team also wanted to demonstrate that entanglement using polarisation of light was possible. Previously it was thought impossible in submarine conditions, even though it has some very technologically convenient properties.

Two years and several complex experiments later, Xuereb and his team have indeed proven the possibility of quantum communications over submarine telecommunication networks. And with one question answered, a slew more lifted their heads.

The Italian subteam, led by Davide Calonico (Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca Metrologica, INRIM), now turned their attention to a different set of questions for the Malta-Sicily telecommunication network.

MORE TO COME…

Atomic clocks keep the world ticking by providing precise timekeeping for GPS navigation, internet synchronisation, banking transactions, and particle science experiments. In all these activities, exact timing is essential.

These extremely accurate clocks use atomic oscillations as a frequency reference, giving them an average error of only one second every 100 million years. Connecting the world’s atomic clocks would create an international common time base, which would allow people to better synchronise their activities, even over vast distances. For example, bank transactions and trading could happen much faster than they do at present.

This can’t be done by bouncing signals off of spaceborne satellites, since tiny changes in the atmosphere or in satellite orbits can ruin the signal. This is where the fibre-optic network comes back into the picture. Researchers have recently been looking at the telecoms network as a way to make this synchronisation possible. Scientists can use an ultra-stable laser to shine a reference beam along these fibres. Monitoring the optical path and the phase of the optical signal of the beam can then allow them to compare and synchronise the clocks at both ends.

Whilst Calonico and his team were testing this idea on the submarine network between Malta and Sicily, a few thousand kilometres away, meteorology expert Dr Giuseppe Marra was monitoring an 80km link in England. On October 2016, everything changed. One night, he noticed some noise in his data. Unable to attribute the noise to misbehaving equipment or a monitoring malfunction, his gut told him to turn to the news from his home country, Italy. There, he saw that the town of Amatrice had been devastated by an earthquake of 5.9 magnitude.

Further testing confirmed that the waveforms Marra saw in the fibre data matched those recorded by the British Geological Survey during the earthquake. His system even recorded quakes as far away as New Zealand, Mexico and Japan. This was huge news.

In simple terms, the seismic waves from an earthquake tremor cause a series of very slight expansions and contractions in fibre-optic cables, which in turn modify the phase of the cable’s reference beam. These tiny disturbances can be captured by specialised measurement tools at the ends of the cable, capable of detecting changes on the scale of femtoseconds: a millionth of a billionth of a second.

The majority of seismometers are land-based and so small that earthquakes more than a few hundred kilometres from the coast go undetected. Conventional seismometers designed to monitor the seabed are expensive and don’t usually monitor underwater seismic activity in real time. Telecoms networks could offer a solution that would allow us to observe and understand seismic activity in the world’s vast oceans. They would open up a new window through which to observe the processes taking place underneath Earth’s surface, teaching us more about how our planet works. In future, it may even make it possible to detect large earthquakes that cause untold devastation earlier.

The beauty of this discovery is that the infrastructure already exists. No new work is needed. All that is required is to set up lasers at either end of these cables, using up a tiny portion of a cable’s bandwidth without interfering with its use.

THREADS COMING TOGETHER

Marra got together with Xuereb and Calonico, who were already working on the undersea network between Malta and Sicily, to conduct some initial tests. The underwater trial, published in the world-leading journal Science this year along with the terrestrial results, was able to detect a weak tremor of 3.4 magnitude off Malta’s coast. Its epicentre was 89km from the cable’s nearest point, which reinforced the idea that cables can be used as a global seismic detector. ‘We would be able to monitor in real time tiny vibrations all over the planet. This would turn the existing network into a microphone for the Earth,’ Xuereb explains.

If we don’t fund the initial few steps of the innovation lifecycle,

how will we ever develop new technologies?

The system hasn’t been tested on an ocean cable. An interesting target would be a cable that crosses the mid-Atlantic ridge, where the drifting of Eurasian and African tectonic plates creates an area of high seismic activity. Based on the results so far and on conservative assumptions, trials are being planned for the near future on a larger scale, which will give us a better idea of the possibilities.

FURTHER DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE…

In many ways, it is understandable that agencies that fund science favour smaller, more goal-driven research programmes. They seek tangible results in a timely manner to reap quick rewards. But as this story goes to show, a change in mentality is needed.

‘If we don’t fund the initial few steps of the innovation lifecycle, how will we ever develop new technologies? This is a problem that affects scientists from many countries and comes from a mismatch in timescales. A year is a long time in politics, but a decade is often a short time in science,’ Xuereb comments.

Innovation has to start from somewhere, and it often starts from ideas which may have no apparent relevance to our everyday lives. We need to support researchers by keeping an open mind to unknown long-term possibilities—or the world might not only miss the next earthquake but also the next life-changing discovery.

Author: Sara Cameron

A scientist and a linguist board a helicopter…

A scientist and a linguist board a helicopter, and the scientist says to the linguist, ‘What is the cornerstone of civilisation, science or language?’ It might sound like the opening line of a joke, but it’s actually from the opening sequence of the film Arrival (2016). In the film, aliens have landed on our doorstep, and our scientist and linguist have been chosen as suitable emissaries to establish contact. The scientist, perhaps wishing to size up his new colleague, then poses the question. Whose field has been more important to the advancement of the human race? Science or language?

In reality, they are both wrong (or both half-right). It is true that language was necessary for us to organise as a species, forming complex networks of cooperation over vast distances and time. Without specialising our efforts and collaborating, we could not have built our great structures, supported large communities, or migrated over all continents. Yet, without science, without improving our understanding of the natural world, we would still be at its mercy.

Science is the tool we use to change circumstance. When populations are dying from an infectious disease, we create a vaccine. When we’re unable to grow enough food to support ourselves, we develop a better strain of crop. When we struggle to transport materials over great distances, we create machines that will do it for us. Science is our secret weapon, transforming problems into possibilities. However, science alone means little. If innovation dies with its creator, who does it help? Science must be communicated to others before it can make a difference in any meaningful way.

It would be incomplete to bestow language or science with the title of ‘the cornerstone of civilisation.’ It was science communication that really drove our development. And I don’t just mean this in the external sense. After all, is the transfer of genetic information from one generation to the next not science communication? What are we but a biological game of Chinese Whispers, the message mutating through each host but somehow continuing to make sense over millions of years?

The human race not only benefits greatly from science communication; we are the product of it. It is embedded into our biological and cultural history. Proof that it is not just knowledge but the sharing of knowledge that is the real root of power.

Hopefully the aliens agree.

Author: Amanda Mathieson

Entering the Age of the Blockchain of Things

What happens when you put smart washing machines on a blockchain?

In writing this article, Dr Joshua Ellul and Prof. Gordon Pace explain their investigation into how to combine the interconnectedness of all things promised by the Internet of Things with the trust promised by blockchain technologies.Continue reading