Marine litter is a problem found across the world. As well as being directly deposited in seas and oceans, plastic, wood, rope, and other items are accumulating on land and making their way into bodies of water. On the Maltese Islands, such littering happens frequently. Last summer the Physical Oceanography Research Group (Faculty of Science, University of Malta [UM]) took a step towards tackling the issue.

Under the supervision of Prof. Alan Deidun and Adam Gauci, I sought to harness innovative techniques and create a monitoring programme that would begin to identify what kind of litter is on Malta and Gozo’s beaches.

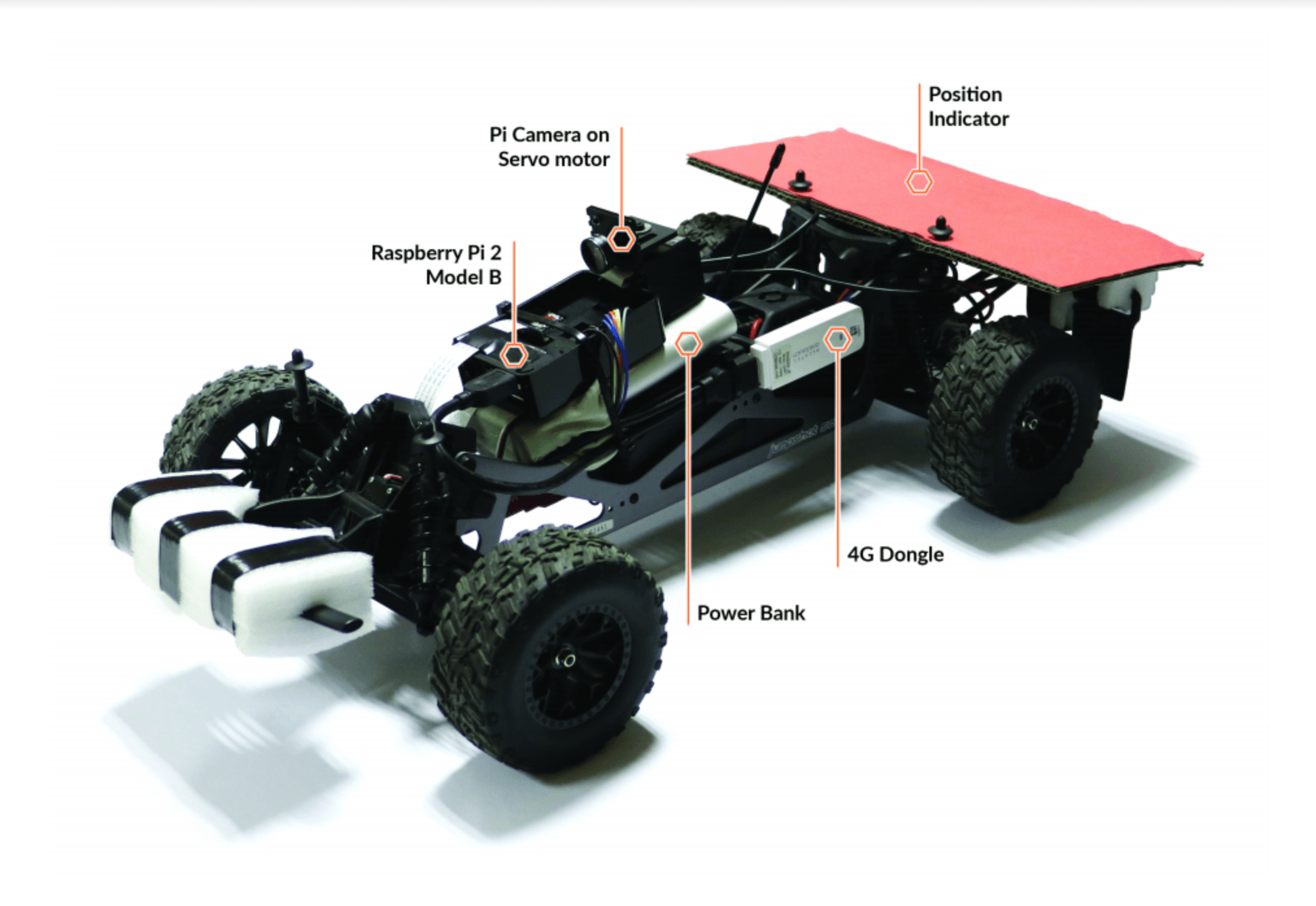

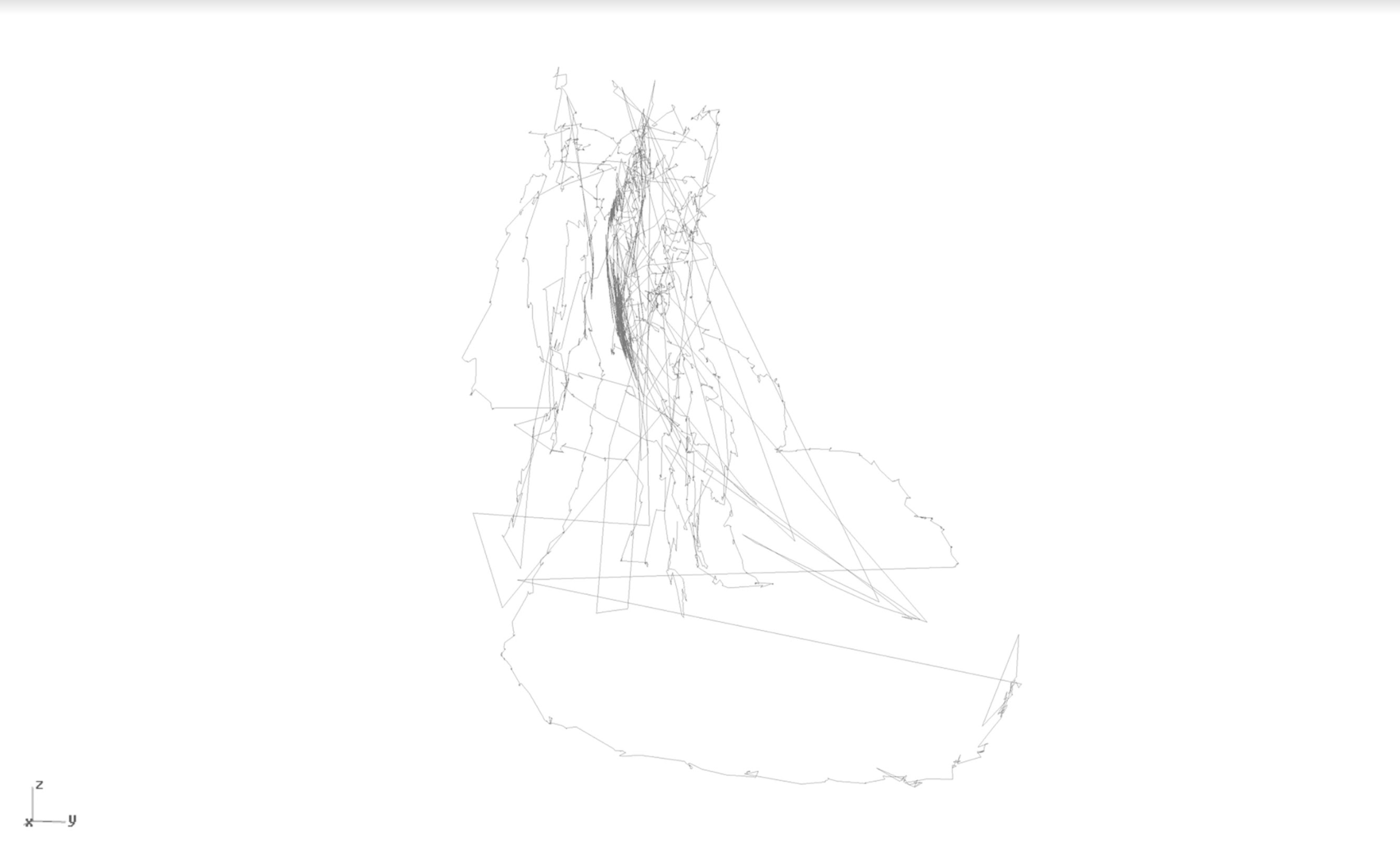

The national Marine Strategy Framework Directive was followed to ensure good data collection and meeting of the ‘Good Environmental Status’ by 2020. The study used images captured by a drone in three coastline areas: the north east Marine Protected Area of Malta, Qawra Point, and the eastern and western points of Baħar Iċ-Ċagħaq. Flying at an altitude of 30 meters, the drone was programmed to spot specific categories of marine and coastal litter. These included plastic, wood, rope, rubber, and other miscellaneous items such as washing machines and mattresses.

Apart from characterising marine litter, the project aimed to observe whether hydrodynamical phenomena, such as wind and currents, are also influencing the accumulation of litter. However, results showed that the difference between the areas of study was not due to dynamics of coastal currents and coastal topography, but to human activities. In Baħar iċ-Ċagħaq, for example, categories such as wood and plastic were found on land at considerable distances from the shoreline, close to points easily accessible by cars.

We also used statistical analyses to confirm that parameters such as tourism, lack of public knowledge, and lack of environmental consciousness are affecting the accumulation of marine litter, laying the blame firmly on human activities.

The remedy to the situation is in Maltese citizens’ hands. Only we have the power to turn things around. It’s time to clean up our act.

This research was carried out as part of a Masters in Physical Oceanography, Faculty of Science, UM.