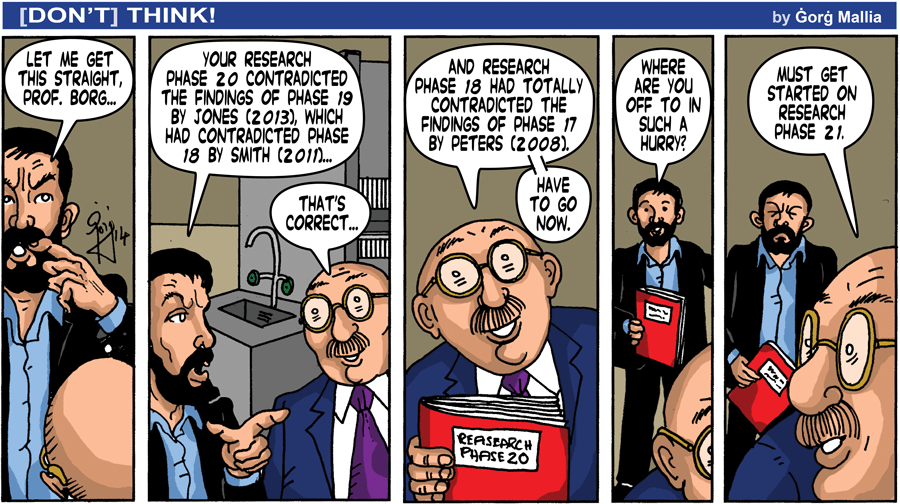

The Valletta 2018 Foundation recently started a five-year research study to evaluate and monitor the European Capital of Culture (ECoC) project in Malta. The process combines both quantitative and qualitative approaches to collect data that will be communicated to the general public and interested stakeholders. This research will provide feedback to help fine-tune or correct the Foundation’s operations. The process aims to provide a local model for research in culture and the creative sector in order to encourage more cultural research after 2018.Continue reading

The mystery of St Paul’s shipwreck

Malta’s identity is deeply intertwined with St Paul. The Islanders have even named a whole bay after him. However there is no hard evidence that St Paul was actually shipwrecked in this area. Elaine Gerada Gatt investigates. Illustrations by Whitebeard Illustrations.Continue reading

Pollution around Malta’s Sea

Research by Nicolette FormosaContinue reading

Read my hips, for longer

Research by Josianne CassarContinue reading

Translating Education

Research by Jana Galea

Language,translation,and education: three hot topics on the Maltese Islands.

Malta invests heavily in education with a big chunk of its budget, strength, and efforts invested to elevate standards. Malta is also largely bilingual. This is even reflected in Malta’s constitution which places both Maltese and English as official languages. Yet, deciding on which language to use to teach children is a thorn in the side of Maltese educational institutions. A viable bilingual policy is still needed.

The European Union places great importance on national languages. This policy elevates the importance of all EU languages no matter the country’s size. The EU releases its documents in each language—a boon for Maltese translation studies. However, there is a clear lacuna in terminology and glossaries for education documents.

Jana Galea (supervised by Prof. Anthony Aquilina) translated an international publication on education into Maltese and compiled an accompanying glossary of educational terms. Translators have to adopt the role of terminologists (professionals who research and locate information or past publications to ensure accuracy and consistency in the usage of terms) when working with specialised terminology, a time consuming activity due to the lack of standardised terms. A glossary of educational terms facilitates translation by providing an easy-to-access reference tool that ensures consistent terminology in translations.

The research tries to show that Maltese and English should not be seen as rivals constantly trying to outdo each other. The Maltese language is part of the country’s unique identity, its most democratic tool, and an official EU language. It is strong and continuously growing, as Prof. Manwel Mifsud stated ‘Ilsien żgħir imma sħiħ, ilsien Semitiku imma Ewropew, ħaj u dinamiku’ (A small but complete language, a Semitic language but European, alive and dynamic). Then there is the English language which is Malta’s main linguistic link to the rest of the world and the carrier of scientific, technological, and informational developments—both languages enrich the Maltese Islands.

This research was performed as part of a Master of Arts in Translation at the Faculty of Arts, University of Malta. It is partially funded by STEPS (the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship—Malta). This scholarship is part-financed by the European Union—European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II—Cohesion Policy 2007–2013, ‘Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality of Life’.

The Pool Party: Life at the Extreme

Shrimps, water fleas, waterworts, and pondweeds, this is one wild party. Dry summers with temperatures of over 40 degrees in summer and flooded winters, life in a rockpool is not easy. Decades of research by local ecologists have shed light on this extreme habitat—Dr Sandro Lanfranco, Kelly Briffa, and Sheryl Sammut tell us more.Continue reading

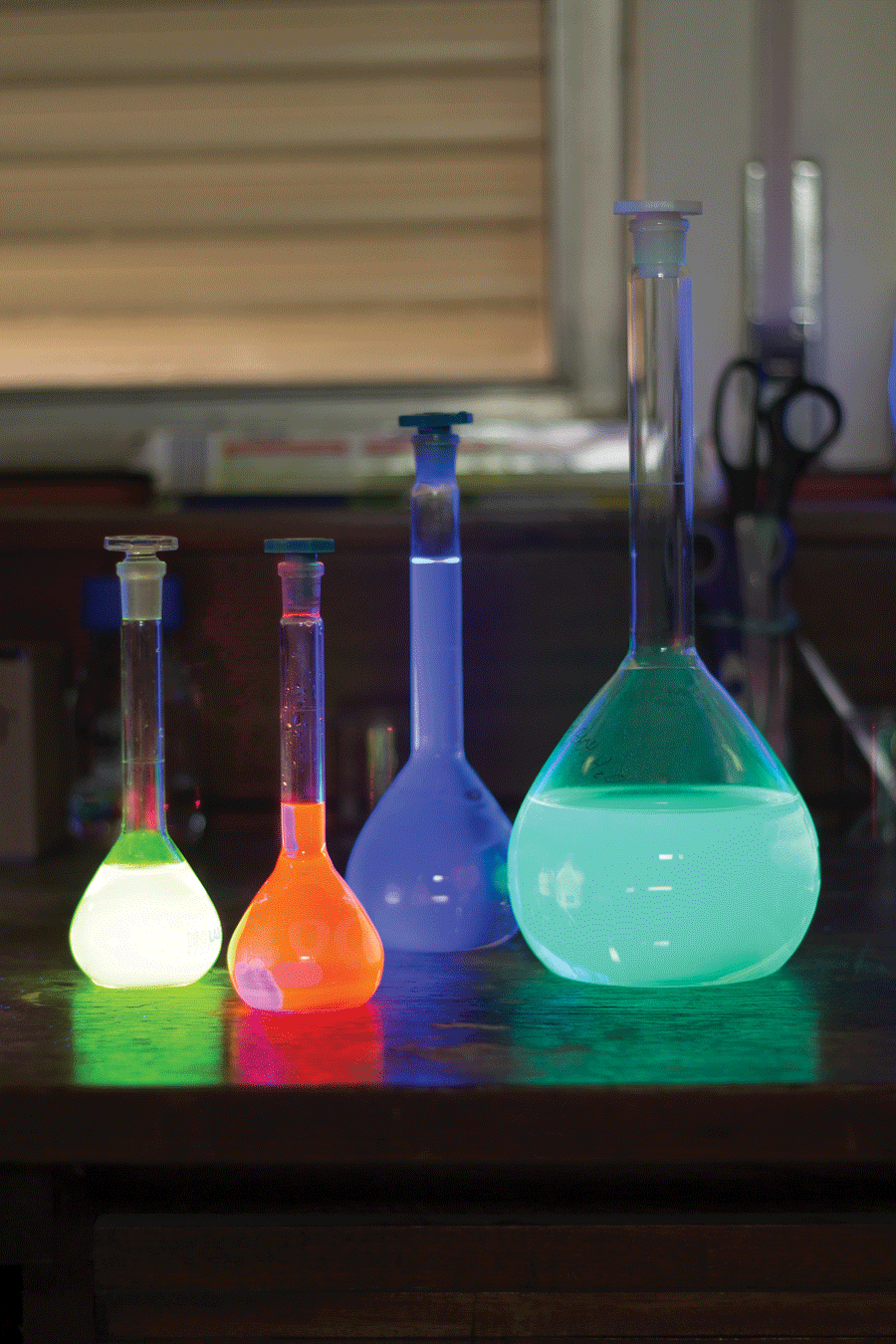

Colouring Chemistry

Smart, logical, and colourful. Dr David Magri and his team develop intelligent molecules. They are not only smart because they perform logical functions, similar to computers, but because they can detect miniscule changes in their surroundings that causes them to emit a large array of colours. These colour changes are intriguing researchers and are a great benefit to society.

Algae Farm

Alexander Hili

What is Malta’s most abundant resource? The sea and sun. Till now very few uses have been found for such resources due to the lack of applications in conventional industries. However, what would happen if we became unconventional?

Think Algae farms. Malta and Gozo could be using the warm waters around them to produce a cheap, healthy food. With copious sunlight prevalent throughout the year, local sushi bars could serve sushi wrapped in local nori. Malta could export to large profitable markets overseas. The farms could provide a large influx of work and increase cash flow to the Maltese Islands.

Don’t Think — September 2014 Edition

Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science

This book was published in 2010 but unfortunately remains one of the few examples of positivity towards Islam coming from the West. British Jim Al-Khalili was born in Iran and he wrote about science during the early days of Islam, also giving a beautiful picture of life before the Islamic revolution of 1979 that forced his family to flee. Al-Khalili is a an accomplished theoretical physicist and broadcast presenter for BBC Horizon, The Big Bang, Tomorrow’s World and Science and Islam (the parallel TV series to this book).

If you love history, you will love this book as Al-Khalili goes into great depth—three whole chapters—to explain the circumstances that led to the golden age of science within Islam. The standard history of science texts usually paints the Islamic Empire (the scientific golden age was mostly from the 8th till 13th century) as being the great saviour of Greek texts having translated the works of Pythagoras, Aristotle, and other Greek scientists that then instigated the Renaissance in Europe when they were translated into Latin and other languages. Al-Khalili shows that these scholars were not mere translators but innovative in Mathematics, Astronomy, Medicine, Chemistry, and other fields. Scholars came from all major faiths.

Al-Khalili takes till Chapter Four to start detailing these scientific achievements. I would have preferred if these came sooner. He reveals facts such as that the zero was not invented by the Arabs but by the Indians, the Arabs simply used it to powerful effect. The Arabs pushed mathematics by leaps and bounds and Al-Khalili uses multiple chapters to outline them all. They invented decimal fractions, part-invented the decimal system, and invented proofs of mathematical equations through induction, using pages of equations to break down the initial equation and prove it absolutely, which is still the gold standard for modern mathematicians.

“He reveals facts such as that the zero was not invented by the Arabs but by the Indians, the Arabs simply used it to powerful effect”

He talks about the polymath al-Razi (854 AD–925 AD). Al-Razi lays claim to classifying substances according to their properties based on experimentation. He used experimentation to select the most hygienic site for Baghdad’s hospital, improved medical ethics and even accepted mentally ill patients (when concurrently the Christian world saw them as devil-possessed), distinguished between curable and incurable disease, clinical trials, and many other advances. His medical textbook al-Kitab al-Hawi fills 23 modern volumes, the largest in the Arab world.

Al-Khalili talks about plenty of other advances and scholars that are sure to surprise readers. The book can be slightly challenging for people to get through. Al-Khalili writes beautifully, clearly, but somewhat academically. If you’re interested in learning about a neglected part of the history of science, this book is for you.

I spoke to Al-Khalili back in 2010 about the TV series related to this book. His final words were that I had to bring his series to Malta. Words relevant then as they are now: a shining light on the possible positivity within Islam interpreted in the right way.