Making children’s voices count

Don’t judge too soon when children enjoy various online tools, says researcher Dr Velislava Hillman — and brings data to prove it.

Continue readingI am online

We’re always warned about what personal details we share on social media. But what does the language people use on platforms like Facebook and Twitter tell us about their wellbeing? Words by Dr Olga Bogolyubova.

Today being an Internet user means being a social media user. The two have become synonymous.

According to the Global Web Index report, there are now over three billion people worldwide using at least one social networking site. The average Internet user has eight social media accounts and is active on at least three platforms. In our contemporary world, most of us spend a significant chunk of our lives online.

This is a modern reality: we access information online, purchase goods and services online, search for jobs online, follow professional interests online, schedule events online, invest in relationships online (some of them purely virtual), and then spend the remaining idle time browsing through our news feeds.

Humans are social creatures, and like other big apes we care about hierarchies and group status. This is reflected in our behaviour on social media, where we actively engage in impression management. We select aspects of our lives to present online in the hopes that they will bring us more benefits, while editing out other parts that could cause negative consequences.

We want to look happy, popular, rich, and successful, or if that doesn’t work, at least try to come across as dramatic or alluring. But in a world where the line between reality and the digital world continues to blur, can we really separate our real-life characteristics from our online persona? Can we effectively hide aspects of our offline identity when online? Are we as good at concealing our true selves as we think we are?

Going deep

A few years back, Dr Michal Kosinski and his team set out to find answers to the above questions. They sought to determine if it would be possible to predict individual characteristics (such as age, gender, sexual orientation, and so on) and personality traits from Facebook Likes.

Over 58,000 people volunteered to take part in the study and provided their Facebook Likes, demographic data, and answers to a set of psychometric measures.

Ethnic origin and gender were predicted from Likes with the highest level of accuracy (95% and 93%, respectively). Prediction of religion, political preferences, and sexual orientation was also good, with 75% to 85% accuracy. However, predicting personality traits turned out to be somewhat more difficult.

In psychology, personality traits are described as characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours and, by definition, these are latent variables, meaning that they are not directly observable but derived from answers to a set of questions. Even so, Kosinski’s research team did manage to demonstrate significant connections between the study participants’ personality traits and their Facebook Likes, with the trait of Openness showing the best predictive potential.

The study has attracted a lot of attention. Other researchers have since been attempting to predict individual characteristics from various features of social media profiles. At first glance, some of the findings may look strange or even absurd. For instance, in one of the studies aimed at predicting personality traits from profile pictures, it was found that extroverted people are less likely to have profile pictures with nostrils showing. Sounds ridiculous… but it actually makes sense if you think about it. By definition, extroverted individuals are more likely to be mindful of other people’s perceptions of them, more likely to see themselves from another’s point of view. As a result, they’ll post better selfies and profile pictures when compared to introverts, who are more likely to upload casual snapshots as profile pictures.

This observation shows that we are unable to control the little details of our behavior. There as so many minute variables involved that it is impossible for us to keep track of them all. A lot of non-vital and therefore ‘unnecessary’ information slips through, yet it reveals a lot about us. This is also found in language. While we usually have no trouble controlling what we say, it is much harder to control how we speak. The topics of our conversations with friends and strangers are firmly under our control, but our use of pronouns and articles in everyday conversations is not. The style of our language is invisible to us.

Honing in on the invisible

James Pennebaker, Professor of Psychology at the University of Texas, USA, was among the first behavioural scientists to propose computational approaches for the study of these invisible, functional components of language.

Pennebaker’s research demonstrated that it is these ‘stealth’ elements that connect deeply with our psychological makeup and state of mind. His ideas provided a starting point for a lot of current social media-based research. After all, our online presence is still largely text-based and rooted in language, and it is only natural that a lot of social media research is based on linguistic analysis.

Many studies are exploring predictors of how online language is being used. For instance, in a recent Facebook-based study, conducted in collaboration with my colleagues from St. Petersburg State University, Russia, we explored connections between subjective wellbeing (i.e. level of satisfaction with one’s life and positive emotionality) and language used in wall posts.

We were able to show that individuals with lower levels of subjective wellbeing are more likely to use ‘should statements’ in their language. In psychotherapy there is a long-standing tradition to regard ‘should statements’ as a type of irrational thinking associated with distress and mental health problems. It is interesting that we were able to demonstrate the relevance of these classic, pre-Internet theories to the contemporary world.

Identifying markers of mental health problems in online language is another important strand of research. Anxiety and mood disorders are the most common mental health conditions, responsible for a significant burden worldwide. They are also treatable, so early identification is vitally important, and social media may provide a platform for screening, psychoeducation, and connection to treatment (including affordable digital interventions). Research can change these citizens’ lives.

Social media-based research on mental health disorders has consistently found an increased use of first person pronouns (I, me) by people with depression. The finding reflects the painful self-centeredness of the mind in mental illness. Some other findings include observations on language use in post traumatic stress disorder, seasonal affective disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder, as well as on identification of suicide risk.

Social media can be risky, but is it the monster we are seeing splattered all over mainstream media? Research can help build systems that bring mental health interventions to low resource regions, and it can aid in identification of suicide risk and risk of violence. Ultimately, it can promote healthy living and save lives.

Maltese Gaming Goes Global

With ever more digital games companies opening their doors in Malta, standing out can be difficult. Dawn Gillies talks to Dorado Games co-founder Simon Dotschuweit to find out how a small company is carving out its niche in an industry of big players.

In 1974, long before the Internet was around, Mazewar introduced the world’s first computer-generated virtual world. With a serial cable to connect computers, friends could play over a network, competing with and against one another for the first time. The Internet now allows thousands of people from opposite sides of the globe to battle it out simultaneously in games set in online virtual worlds like World of Warcraft.

Digital gaming is an industry on the rise, and Malta has seen success after success. It’s a multi-billion dollar enterprise, taking in an astounding $30.7 bn globally in 2017 alone according to Statista. In recent years there has been a surge in free-to-play online games. With so many free games competing for our attention, you might wonder where the money comes from. It may seem counterintuitive, but these free online games sometimes generate higher profits than paid counterparts. Multiplayer PC beat ’em up Dungeon Fighter Online reportedly made an astonishing $1.6 bn in 2017.

With more than 30 digital games companies in Malta alone, it’s a competitive industry to take on. Yet Simon Dotschuweit and Nick Porsche have created Dorado Games, launched real-time grand-strategy game Conflict of Nations, and gained over 400,000 customers.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game.

Dorado’s Origin Story

Whilst working for the independent creators, publishers, and distributors of digital games Stillfront Group, Dotschuweit was already mulling over some new game ideas. The game engines, platforms, and building blocks were all at his disposal. What he needed was a collaborator. That was when Nick Porsche appeared on the scene.

Porsche and Dotschuweit brought different skills to the table: Dotschuweit came from an IT and technology background, while Porsche gained his experience as creative director for the Battlestar Galactica online game. Their ideas had Stillfront interested. They were in the early stages of building a game, and the endeavour was gaining support. ‘It was going well, and the company wanted to go ahead with it.’ Two years later, Dorado Games was acquired by the Stillfront Group.

When most of us think video games, we immediately think of games consoles. So why choose to create an online game? Or, for that matter, one that’s free?

Dotschuweit says, ‘They’re a lot more fun to do. You have more control. Usually you self-publish. You can do stuff more iteratively. You can release and then improve. With console games, you need a large publishing partner that will take a large portion of the revenue.’ With Dorado constantly striving to improve their online world for players, the ability to continually update was a big draw for them.

The world of online gaming better lends itself to strategy games. With Dotschuweit and Porsche already big fans, their goal was to create a game they wanted to play. Their business model is also better suited to online gaming than consoles. ‘It’s free to play, so we incentivise players to pay for extra features, which doesn’t work well on console.’ This is where the money comes from. Players pay to construct buildings or train their troops more quickly, giving them an advantage over the competition.

But Stillfront’s acquisition of Dorado meant it was decision time for Dotschuweit. He had to choose between keeping his comfortable job with Stillfront, or taking on a new challenge in the startup world. Living in China with his family at the time, the ramifications of that decision were huge. Porsche was already in Malta, incentivised by the Maltese government’s support of new businesses. In the end, Dotschuweit felt the opportunity to join forces was too great to pass up. He made the leap.

The Rise to Success

Money was key. Dotschuweit tells us, ‘We managed to secure quite a sizeable employment-based grant from Malta Enterprise for our company, which was of course a very nice plus. And Malta is a really nice place!’ The grant not only helped Dorado win over investors, but it reduced risk in an industry that’s infamous for its kill rate, both in-game and in real life. Suffice to say that coming out on top in the gaming world is not guaranteed.

Working in a start-up was also a change for Dotschuweit. Having previously worked for US tech giant IBM, he wanted to make a mark with this new venture. ‘You get to have a lot more impact. Your presence matters a lot more to a small business; it’s a lot more fun. You get to wear lots of hats and get a lot of experience.’ The busy and exciting nature of a small business appealed to him much more than clocking in to a regular office job.

The good times continued rolling with more support coming in from the University of Malta’s (UM) Centre for Entrepreneurship and Business Incubation (CEBI). CEBI houses the TAKEOFF programme which supports new businesses and provides facilities for them. Dr Joseph Bartolo and Prof. Russell Smith are familiar names when it comes to Maltese start-ups, and they have both been an influential part of Dorado’s story. They now operate from the TAKEOFF building on UM’s Msida campus.

But Dorado’s journey is not all smooth sailing. ‘We are a live service and we don’t have separate teams for operations and expansions, so that sometimes means your plans change!’ explains Dotschuweit. It’s all hands on deck to fix any problems. ‘It’s part of the bane and the fun of operations. But it doesn’t get boring!’ he says. This means that a day of meetings can quickly turn into a hectic day of making sure the game is running smoothly. They don’t want to disrupt players’ gameplay if they can avoid it.

In the past, Dorado hired game developers to bring their ideas to life. But this modus operandi changed when it came to Conflict of Nations. With this project, Dotschuweit and Porsche wanted more control, and they were ready to invest. They dug their heels in and hired their own team.

A game of political and military tactics with elements of espionage, Conflict of Nations requires real-world diplomacy skills to move up in the world. Unlike most other strategy games, it takes place right here on Earth, making use of Google Maps to make the game truly global.

Bringing their dream team to life was a challenge. ‘Finding talent back then wasn’t the easiest thing,’ says Dotschuweit. But their perseverance has seen them build a close-knit team who have all contributed to Dorado’s success.

The quest for perfection is a common theme in Dorado’s story. The perfect team, the perfect platform, the perfect game. Their commitment to giving players the best possible experience is a testament to their investment in their projects. Taking the time to get the right team together has proved to be one of the many reasons for Dorado’s fast climb up the games industry ladder. Another was getting their game out quickly to get fan feedback as soon as possible. The Stillfront platform restricts them somewhat in their design, as it wasn’t made specifically for Dorado, by Dorado, but it has reduced their workload massively, allowing them to get Conflict of Nations launch-ready in a fraction of the time. Identifying and taking advantage of opportunities has also been key to their quick rise.

Many Lessons Learnt

In the crowded world of online games, Dorado games has skillfully managed to carve out its place. Real-time negotiations and political tactics in Conflict of Nations are the stand-out features for fans who enjoy the long timescales and mental strategy involved. With this victory under their belt, we’ll soon see more from Dorado. They have plans to develop another game this year.

With years of experience in the industry, Dotschuweit has some advice for any future gaming entrepreneurs. ‘Get it out fast and get feedback. You can always improve it later.’ He notes the success of game jams in turning ideas into businesses and urges people to get involved. So, what are you waiting for?

Author: Dawn Gillies

Cyber-safety in an ever-changing landscape

The threat of infection looms large in the digital world, but a team of University of Malta (UM) alumni have taken it upon themselves to create a cybersecurity system that acts quickly and responds dynamically. Teodor Reljic learns about CyberSift.

Continue reading

The great siege of fake information

Information is under siege.

Where is the crowd?

Athletes who are cheered on during sporting activities are likely to perform better than athletes who don’t. The HeartLink project is investigating how to remotely cheer athletes while they are participating in sporting events. Dr Franco Curmi writes about his work for the HeartLink project.

Continue readingSensory Apparatus

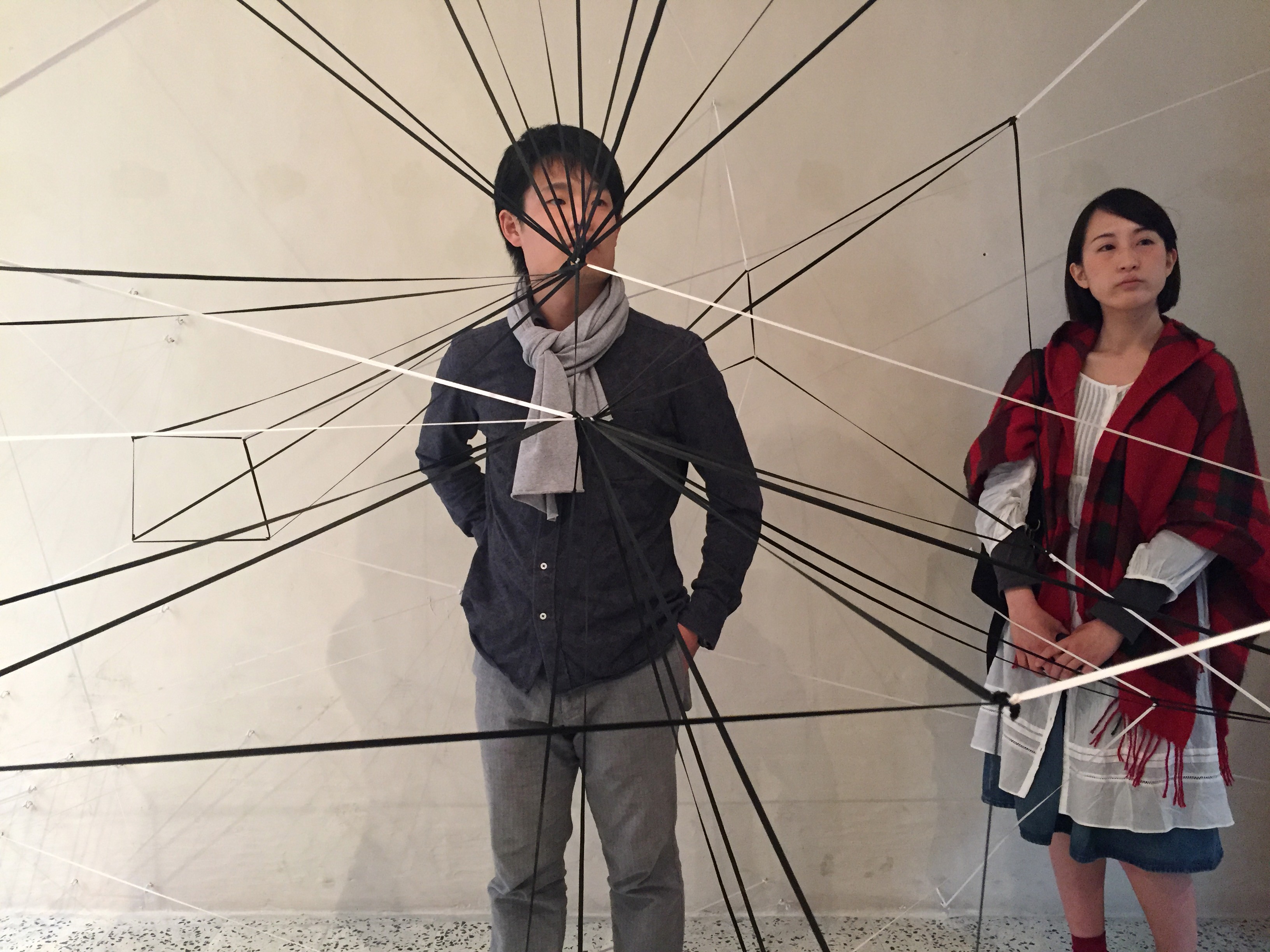

‘What does it really mean to sense something?’ That was the fundamental question Dr Libby Heaney (quantum physicist and artist) asked herself when she started working on Sensory Apparatus, currently on display at Blitz in Valletta. For almost a year she worked together with Bonamy Devas (artist and photographer) and Anna Ridler (designer working with information and data). For Libby sensing means the collection of data. Science tries to measure everything and is now through so-called ‘big data’ attempting to quantify subjective things, like happiness levels or the perfect online dating match.

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

The second room has circuit boards and speakers mounted to the walls. People curious enough will trigger a proximity sensor and a computerised voice starts talking. ‘Name. Country. Age. Address.’ What sounds like nonsense at first, quickly develops into the auditive representation of an algorithm. Passing consecutive speakers continuously reveals its different layers. These algorithms are complex programmes, designed to collect the footprints people leave while online. The information is used by marketers to direct and personalise adverts. ‘We wanted to reveal the technology. The actual objects represent the discussion we are trying to make.’

The last room is pitch black. Only when approaching the middle of the room a projector lights up, projecting advertisements directly onto people’s bodies. The commercial pieces, gathered from across Malta, follow every movement, change constantly and are reflected from the room’s glossy walls. At the exhibition opening, once people noticed they were being used as a billboard, they quickly moved away. ‘People change and behave differently in there’, Libby says, making it obvious how advertisements influence us online.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

The free exhibition opens every Tuesday–Thursday from 10am–3pm and Friday–Saturday from 3–7pm at Blitz, 68 St Lucia Street, Valletta, until April 6. For more information see thisisblitz.com

Sensory Apparatus is supported by Arts Council Malta / Malta Arts Fund.