Love (in) letters

Literature shapes our understanding of love, from Romeo and Juliet to over-quoted phrases before Valentine’s Day. It continues to influence the way we relate to the complex emotions and quests surrounding love. Literature experts Prof. James Corby and Prof. Adrian Grima (University of Malta) share their thoughts about the cornerstones of the literature of love with Daiva Repeckaite.

Continue readingWhat’s love got to do with it?

While some of us are privileged to be shielded from it, the truth remains — violence in Malta is rampant. From popular songs to neighbours’ conversations, the normalisation of abuse is shaping our communities and our basic understanding of healthy relationships. Words by Cassi Camilleri.

Continue readingTying the second knot

In May 2011, three quarters of the electorate went to cast their vote on whether or not divorce should be legal in Malta. The verdict came in strong with 53% voting in favour of legalising divorce. But how do people really feel about love and remarrying? Words by Emma Clarke.

Continue readingYoung hearts run free

For the first time in Malta, a cardiac screening programme for young people aims to identify who among them are most at risk of sudden cardiac death. Here, Laura Bonnici chats with Dr Mark Abela to learn more about the Beat It project and the impact it is having on young lives across Malta.

There are times in life when death haunts us all. It is most tragic when it strikes down our youth. This year, Italian footballer Davide Astori and Belgian cyclist Michael Goolaerts made headlines after they died unexpectedly. Also making headlines was sudden cardiac death (SCD).

Ischaemic heart disease is the most common cause of cardiac deaths, its likelihood increasing with age. A blockage in one of the arteries supplying the heart starves it of oxygen and nutrients, leading to heart attacks, sometimes resulting in cardiac arrest, in which there is sudden and unexpected loss of electrical heart function. But SCD in young people is very different from cardiac death later in life.

Much like Astori and Goolaerts, SCD victims are generally presumed to be in good health. Early symptoms are often incorrectly attributed to other issues or life changes. The result is a horrendous loss for the sufferer and their family and friends, who also have to weather biological, psychological, and social repercussions. Seeing these events unfold, specialist trainee in Cardiology Dr Mark Abela felt the time was right to offer an SCD screening programme to young people in Malta. He called the project Beat It.

The idea behind Beat It was inspired by the UK-based NGO Cardiac Risk in the Young [CRY], Abela notes. ‘CRY offers screening to young people between 14 and 35 to identify those who might be prone to heart disease. They then give follow-up advice, support, and evaluations accordingly. I realised that a similar programme would be very beneficial to young people here in Malta,’ says Abela.

In Malta, the Beat It project has focused mainly on fifth form students between the ages of 14 and 16. The cardiac screenings attempt to identify those who may be susceptible to SCD, with those prone to it referred to hospital for further tests to catch the condition before it can strike.

‘Because athletes are believed to be at a higher risk for SCD, we need to have routine screening across all sporting disciplines,’ says Abela. ‘Sport has shown the medical community that young individuals who are susceptible to genetic heart disease are still at risk of SCD. Screening helps decrease this burden. Current evidence also supports that this risk is present for non-athletic youths—so why neglect these youngsters?’

Launched officially in October 2017, the Beat It project saw nine doctors, accompanied by a team of technicians and nurses, going into schools and running screenings. Students filled in a simple questionnaire and took an Electrocardiogram (ECG) test on the spot. ‘We analysed the results in the hope of identifying heart disease in the early stages, then advised the young people if they should consider some lifestyle changes,’ says Abela. This included advice ranging from easing up on tennis, to which career choices might be most appropriate for the student based on their health. The team also advised further medical treatment and organised follow-up appointments with specialists Dr Mark Sammut, Dr Tiziana Felice, and Dr Melanie Burg in some instances. In the end, the project screened 2,700 of the 4,300 eligible fifth form students across Maltese schools, all with the support of the school administrators and teachers, who ensured that everything ran smoothly.

The significance of this project could also reach well beyond the lives of the young people themselves. ‘Since the country is so small and families are often inter-connected, genetic diseases in Malta tend to be more prominent,’ Abela emphasised. ‘The discovery of susceptibility to hereditary cardiac disease in any young person therefore also suggests that their parents or siblings may be at risk of SCD. With appropriate testing, the ripple effect of Beat It could preempt problems in entire families, maybe even saving someone’s life in the process.’

The project boosted awareness of cardiac disease and SCD for Maltese young people, their parents, and their teachers. UK data reports that eight out of 10 young deaths do not report symptoms beforehand. There is also a tendency for symptoms to be downplayed by educators who are not aware of potential problems. With this in mind, Beat It will also act as a learning platform. Since young people with cardiac abnormalities are at higher risk for exercise-related symptoms, physical education teachers are now more aware about potential red flags.

Celebrating the completion of the Beat It project, Abela expressed his gratitude for the team who made it possible. ‘The incredible dedication and teamwork of everyone involved has helped Beat It to effect positive change in young people’s lives, potentially saving some in the process.’

Note: The Beat It project is a collaboration between the Cardiology Department at Mater Dei Hospital, the Ministry of Education, the University of Malta, and the Malta Heart Foundation and is supported by corporate sponsors including Cherubino Ltd. through the Research, Innovation and Development Trust (RIDT) and TrioMed.

Author: Laura Bonnici

Through the VR glass

As societies evolve and take in a greater number of distinct cultures, histories, and traditions, the ability to empathise with each other becomes vital, for all our sakes. In an effort to get as close as possible to seeing life through another’s eyes, researchers from the University of Malta are creating a virtual reality experience that allows users to step into someone else’s shoes.

Words by Dr Vanessa Camilleri.

From a young age we are often taught that if we want to understand someone else’s perspective, we must first walk a mile in their shoes. This ability to place ourselves in another’s position is what we call empathy. This component of emotional intelligence is known to increase prosocial behaviour and reduce individualistic traits, meaning that it can lead to a better quality of life where practiced, whether at home, in the workplace, or any other environment.

Where is the crowd?

Athletes who are cheered on during sporting activities are likely to perform better than athletes who don’t. The HeartLink project is investigating how to remotely cheer athletes while they are participating in sporting events. Dr Franco Curmi writes about his work for the HeartLink project.

Continue readingNMR, Kidneys and a Family

I chose to study Chemistry and Physics simply because they were the subjects I enjoyed most, so I enrolled on a B.Sc. (Hons) degree at the University of Malta without having a clear idea about what I would be doing once the four years are over. I was not the best brain in the class but in 2004 I graduated with a 2:1 grade and it was quite obvious that I needed a plan. A couple of opportunities to embark on a Ph.D. in Britain came along through local contacts and applications on jobs websites. Despite not knowing much about the subject, I decided to go with the Ph.D. at Exeter University because it was about Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, a subject that sits right on the verge of Chemistry and Physics.

Obviously the idea of moving abroad, living away from my parents and starting this amazing new adventure was incredibly exciting. From the start of my Ph.D. things went incredibly well, it was immediately obvious that I was much better at doing research than studying for exams. I started with looking into dynamics in solid materials on the microsecond timescale, which is the less studied type of motion. It bridges the gap between very fast (spin-lattice relaxation motions, nanosecond) and slow (millisecond to second) timescales. I published my first scientific paper a year into my Ph.D., and five more followed by the time I defended my thesis.

Because of the contacts I built during my Ph.D. as soon as I finished I was offered a post at University College London, Institute of Child Health, working as a research fellow in renal imaging. I carry out research at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital using novel non-invasive Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) techniques. I work mainly with children requiring a kidney transplant. The aim of my work is to eventually be able to furnish doctors with information about their patients, which is currently either unavailable to them or they can only get through invasive clinical techniques such as biopsies. My work here has produced six peer-reviewed papers and I am currently working on a few more.

The research I carried out during my Ph.D. involved dealing with basic scientific concepts like Quantum Mechanics — that studies sub-atomic phenomena — and I was at liberty to experiment as I saw fit, which I enjoyed. However, despite being much more restrictive, I find clinical research extremely rewarding. Coming face to face with the people benefiting from all your hard work is really priceless.

Just after my Ph.D. I married my husband. We are now very proud parents of a two-year-old son. Any working mum would tell you that raising a family while maintaining a career is not easy, but I believe that if you like your job enough, combing the two is very worthwhile. Obviously research does not wait for anyone, and luckily for me, having colleagues that supported me meant that I was able to carry on publishing while I was on maternity leave.

It’s all in the family

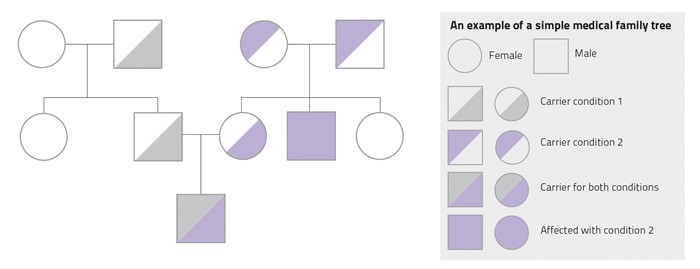

Whatever you inherit comes from your biological family. Unfortunately, this includes disease. Talking about inherited conditions can make people anxious, making them unwilling to discuss the issue with their relatives. After speaking to a number of people my impression is that it seems taboo to discuss these things. People seem to feel that they will be stigmatised or treated differently because of a genetic condition.

A fear of social stigma hinders beneficial research. Research needs the collaboration of patients, since by investigating their condition researchers can in the long run develop a treatment or therapy. Not only that, but avoiding certain discussions means that relatives who might be at risk of developing the same problem would not be aware of it. If a condition is detected too late there might be very little that can be done.

It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together. By building a medical family tree you can easily see who might inherit what. This way, your relatives will learn more about their health and then seek treatment. For example, a cousin might learn that she has an increased risk of breast cancer and would therefore attend screening sessions to catch the cancer before it spreads. Not knowing that something is there does not make it go away but discussing medical matters with your family could save a relative’s life.

“It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together”

Scientific studies need family medical information. Scientific studies using family trees have already shown how useful this information is in identifying families with a high risk for inheritable cancers, like colon and breast cancer. Other research showed that families can benefit from preventative treatments against cardiovascular diseases like diabetes.

Local research has recently used this technique to find new genes, knowledge that can be developed for new treatments. The researchers were studying the genetic background of the protein which carries oxygen in our blood, haemoglobin. This protein switches from foetal haemoglobin to adult haemoglobin 3–6 months after birth. People with thalassemia have a problem with the adult version. Therefore, by studying local families that naturally cope well with the disease, they discovered the KLF1 gene that compensates for the malfunctioning adult protein by raising foetal haemoglobin levels. This was only possible with the help of family trees.

Speaking to a doctor to prepare a medical family tree (pictured) is done in the strictest confidentiality. You may also create your family medical history on https://familyhistory.hhs.gov/fhh-web/home.action to discuss with your family and doctor. I believe that it is in our best interest, apart from being potentially beneficial to the rest of humankind, to help in the creation of our own family medical trees.

If you have any queries when your physician or consultant asks you to prepare a family tree feel free to discuss them rather than avoiding family trees.