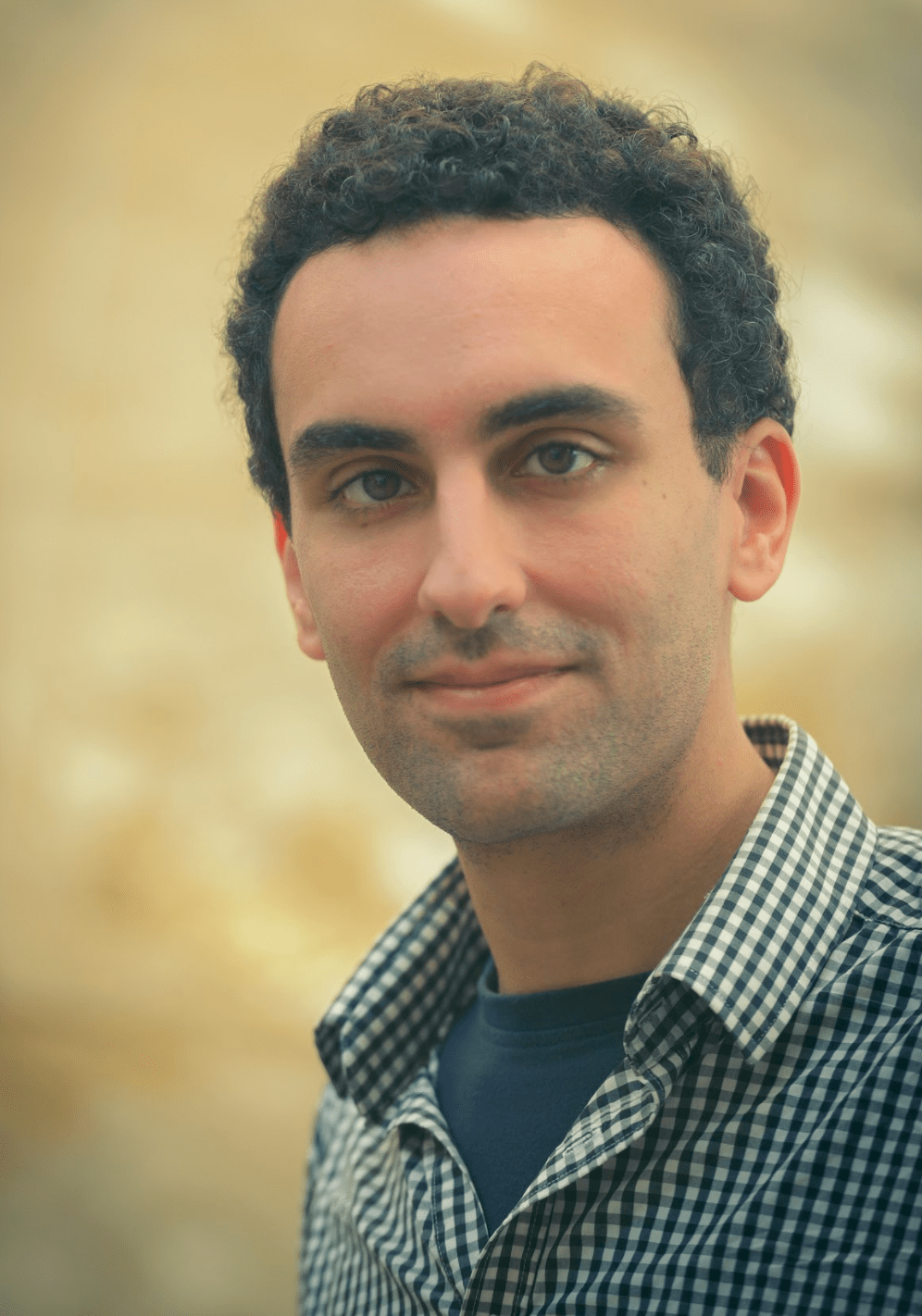

EcoMarine Malta’s boat tours are leading the way in environmentally sustainable tourism around the Maltese Islands. Founder Patrizia Patti talks to Edward Thomas about how economic success doesn’t need to be sacrificed in order to protect nature.

Aquarter of Malta’s GDP comes from the tourism industry. It accounts for €2 billion annually and shows no sign of slowing down. Tourist expenditure went up by 13.9% from 2016 to 2017 alone. It constitutes one in every seven jobs in the local economy and maintains a close link to development: better hotels, improved roads, more diverse shops and restaurants. Beyond the economic benefits, tourism promotes and celebrates local customs, food, traditions, and festivals, creating a sense of civic pride.

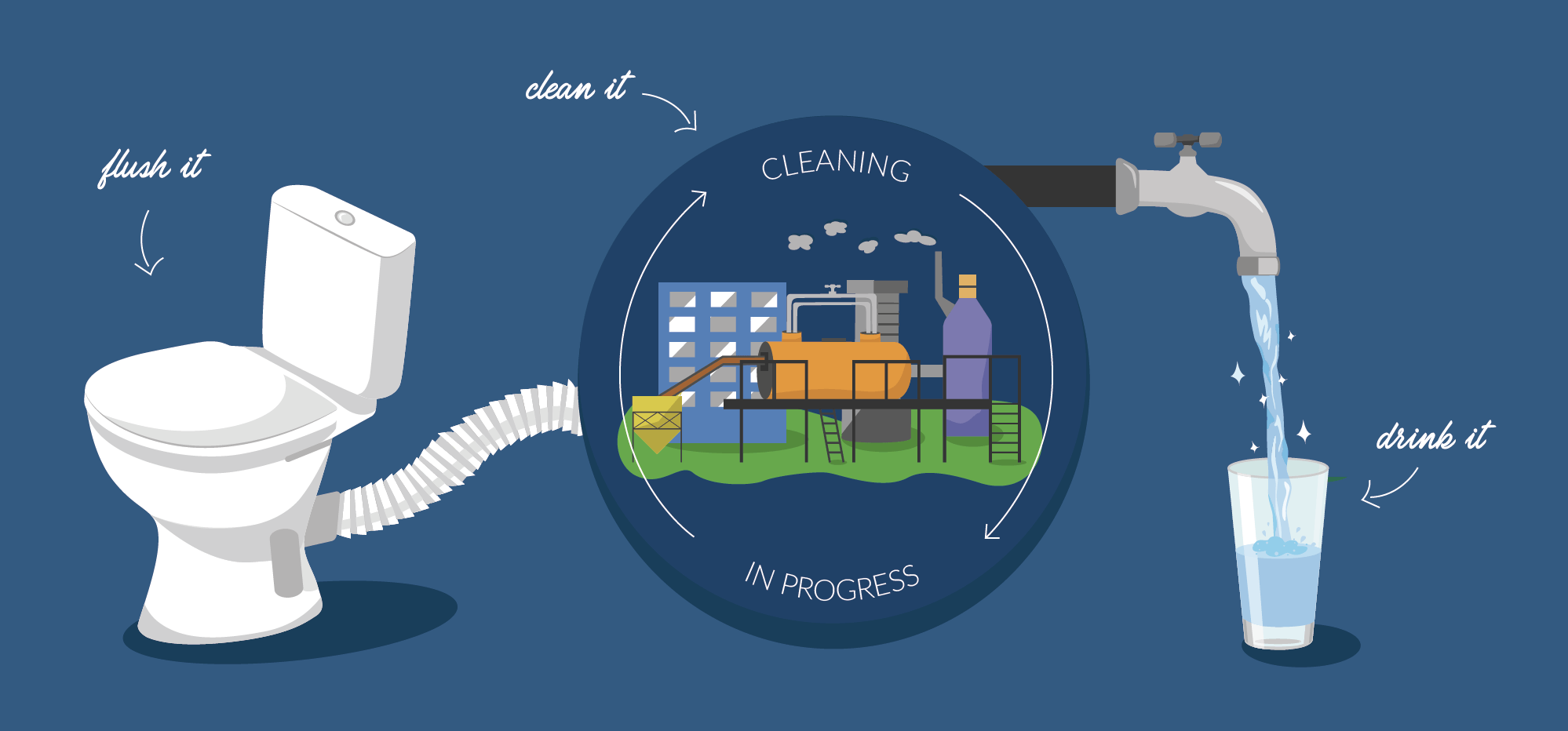

However, there are concerns. In July and August, Malta, Gozo, and Comino are covered by thousands of holiday-makers flocking in. This is a not only a burden on already strained island resources and infrastructure including water, waste management, and traffic congestion, but it pushes many coastal habitats and aquatic ecosystems to the breaking point, with drastic impacts on local biodiversity.

Marine biologist Patrizia Patti laments how ‘people go with speed boats to Comino carrying beers, drinking, throwing bottles into the sea, playing loud music… it disturbs everything.’ If larger tour companies made a small effort to be more responsible, it could have a large effect, she says. ‘Even a simple announcement on a microphone, reminding people they are in a protected area and to behave in a certain way, advising people to respect nature, would help. It’s only a small reminder but it would help a lot.’ Always looking to lead by example, and to show that small actions can have a great impact, Patti set up EcoMarine Malta. The start up organises responsible boat tours around the island, where the international code of conduct is followed and people can experience the joy of encountering dolphins, turtles, and seabirds in their natural habitat.

FACE TO FACE

Patti says their goal is to establish profound personal connections between people and the sea in the hopes that it will change behaviour. She has been passionate about marine biology since the age of 17, when she first encountered a dolphin. That happened during a school trip to an aquarium. She says ‘it was exciting because it was the first time I saw a dolphin, but it was terrible seeing it trapped in a small tank. It made me so sad.’ The emotional response was strong enough to move Patti to tears. ‘It was at that point I decided I wanted to become a marine biologist. I wanted to help.’

Patti went on to study the ecology of sperm whales in the Ligurian Sea before travelling far and wide, gaining experience working with marine mammals in Canada, the Maldives, and the Red Sea. In 2013, she cofounded Costa Balenae Whale and Nature Watching in Italy, a company, like Eco Marine Malta, which strongly focuses on bringing humans closer to marine wildlife, forming lasting memories that inspire them to consider their environmental impact and educating both children and adults about the natural biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea.

How can you love something and want to protect it when you’ve never seen it?

Seeing these animals and experiencing their natural environment first hand is vital to establishing an emotional bond. This is what then engages people and inspires them to change their behaviour. ‘How can you love something and want to protect it when you’ve never seen it?’ Patti questions. By opening local and tourists’ eyes to the majesty of indigenous species, EcoMarine Malta create compassion and motivate people to take responsibility for the environment too. They also chip away at the sense of helplessness many feel when it comes to ‘actually making a difference.’ EcoMarine Malta provide education and information for their passengers to follow. Patti, who leads the tours herself, goes into how they can enjoy Malta’s beaches responsibly and sustainably, empowering them to take ownership for their actions and decisions before it’s too late.

MONEY PROBLEMS

It’s not always been plain sailing for EcoMarine Malta and their boat trips. Patti firmly believes that environmental conservation can be a tool to increase economic growth and employment in Malta. ‘Even if we act like an NGO, we decided to be a private company

because we want to create job places and grow and be able to provide the best service possible,’ Patti says. But not everyone agrees. Patti has received plenty of push back from others in the field as she lobbies for best practices to be enforced around the islands.

Some views are severely narrow and short-sighted, rooted in the belief that any sort of restriction of operations is bad, even if inspired by respect and protection for the natural resources they use. ‘People have to understand that a protected area is to enjoy for a long time. Maybe not now, maybe for one or two years you have to be careful, you can’t do everything you want to do. But after those two years, you can enjoy a new beautiful area, rich in life,’ explains Patti. Setting up EcoMarine Malta as a for-profit enterprise to prove these people wrong, however, has led to another kettle of fish. Because they’re not an NGO, applying for sponsorship and funding is a major challenge. Potential benefactors often dismiss collaboration, telling Patti that the company should be able to support its own endeavours.

This lack of support saw EcoMarine Malta having to rent boats from various charter companies, a massive expense. Externally renting a boat brought with it uncertainty and inflexibility. Last-minute dropouts or weather changes forced them to cancel tours and lose a lot of money. ‘The boat rental still had to paid for,’ she says. But things are looking up. EcoMarine Malta purchased their own boat this summer, and Patti is working hard on getting all the permits in place to have it out on the water as soon as possible. ‘Now we will be able to plan our own routes and diversify the tours we offer. At the moment, we have six tours available to choose from, including a sunset tour when marine life is at its most active,’ she smiles.

GET THEM YOUNG

2018 might be EcoMarine Malta’s first full summer season, but that doesn’t stop Patti from dreaming big about their future. She and her team want to do more outreach and education and are working on offering a series of courses for students aged between 10 and 16 years old. These children will be able to participate in a day of hands-on classroom activities, discovering and learning about sustainability and the ecosystem of the Mediterranean, followed by a boat trip to implement their new knowledge, observing and identifying the variety of wildlife and nature surrounding them and their island. ‘We hope to inspire a whole new generation of marine biologists and environmental scientists,’ Patti says.

With an army of environmentalists in the making, Patti hopes they will take over her role in the future. That would allow her to refocus on a passion she is itching to pick up again: searching for evidence of sperm whales in the Mediterranean surrounding the Maltese Islands. Her eyes light up as she admits to me, ‘I love outreach, but my personal dream is to spot sperm whales in Malta.’ Researchers know that juvenile and female sperm whales in the Atlantic remain in warm waters while the males migrate to the poles to feed, but movements and social dynamics of pods in the Mediterranean are still unclear.

With an army of environmentalists in the making, Patti hopes they will take over her role in the future.

Looking forward, Patti is working hard to establish networks with other entities and NGOs who share the same vision. EcoMarine Malta already collaborates with the likes of Birdlife Malta and has been involved with beach ‘Clean Up’ projects in the past year. Patti asserts that despite everything, ‘the Maltese public and tourists are some of the most enthusiastic and passionate people we’ve worked with so far. It’s great to see people of all ages and backgrounds, coming together to work on a common goal.’

‘Everyone can contribute different things, and together, it adds up to make a big difference.’ Patti is keen to encourage people to help in whatever way they can. To cooperate with others and not feel overwhelmed or alone in their efforts. ‘It’s not possible to do it alone. We need to work together, holistically, caring about the land, sea, and air, to protect the island’s environment.

Greg Nowell is a diver whose ‘regular’ job involves electronics quality auditing and building renovation works. In 2011, while at a local fish market, Greg noticed something unusual. One of the catsharks on sale had an egg protruding from it. ‘I took it out, and it looked intact. I could see there was something inside,’ he says. He decided to put the egg in an aquarium to see what would happen, and while the shark pup inside developed successfully over the course of a few weeks, it eventually died before the two month mark. Looking back, Nowell can confidently say now that it had everything to do with temperature.

Greg Nowell is a diver whose ‘regular’ job involves electronics quality auditing and building renovation works. In 2011, while at a local fish market, Greg noticed something unusual. One of the catsharks on sale had an egg protruding from it. ‘I took it out, and it looked intact. I could see there was something inside,’ he says. He decided to put the egg in an aquarium to see what would happen, and while the shark pup inside developed successfully over the course of a few weeks, it eventually died before the two month mark. Looking back, Nowell can confidently say now that it had everything to do with temperature. While the initial plan for our interview was to go to the fish market and save the eggs still alive in the female sharks, a storm put an end to those plans. The fishermen couldn’t go out to sea, so we made our way to the Malta National Aquarium instead.

While the initial plan for our interview was to go to the fish market and save the eggs still alive in the female sharks, a storm put an end to those plans. The fishermen couldn’t go out to sea, so we made our way to the Malta National Aquarium instead. But there is more to Sharklab than the sharks themselves, Nowell notes. Towards the end of our trip to the aquarium, he highlights the need for better ecosystem management. ‘The animals, as fascinating as they are, live in an environment,’ he says. That itself deserves attention.

But there is more to Sharklab than the sharks themselves, Nowell notes. Towards the end of our trip to the aquarium, he highlights the need for better ecosystem management. ‘The animals, as fascinating as they are, live in an environment,’ he says. That itself deserves attention.