Gymnastic Polymers

by Alexander Hili

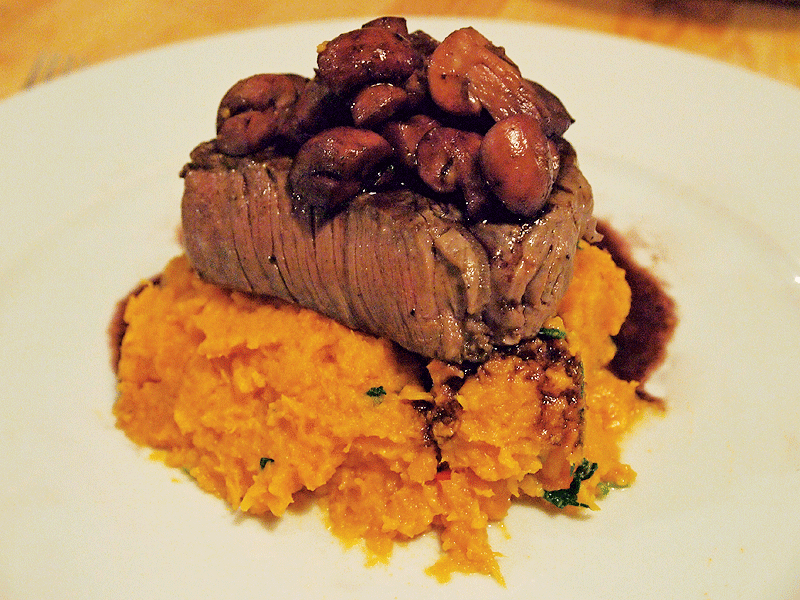

How do you cook the perfect steak?

Fillet is the best cut. Trust me. It’s worth the money.

Use molecular gastronomy to take advantage of decades of researching how meat changes with heat. Science indicates that the best cooking temperature is around 55˚C, and definitely not above 60˚C. At a high temperature, myofibrillar (hold 80% of water) and collagen (hold beef together) proteins shrink. Shrinking leads to water loss. In the water lies the flavour.

To cook the fillet use a technique called sous vide. It involves vacuum wrapping the beef and keeping it at 55˚C in a water bath for 24–72 hours. This breaks down the proteins without over heating. The beef becomes tender but retains flavour and juiciness.

Take the beef out. It will look unpalatable. Quickly fry it on high heat on both sides to brown it. The high heat triggers the reduction of proteins or the Maillard reaction. Enjoy with a glass of your favourite red.

Green Chemistry for the Environment

Producing Food products, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals leads to hazardous waste and poses environmental and health risks. For over 20 years, green chemists have been attempting to transform the chemical industries by designing inherently safer and cleaner processes. Continue reading

Playing with Solid State Benzene

Computational chemistry is a powerful interdisciplinary field where traditional chemistry experiments are replaced by computer simulations. They make use of the underlying physics to calculate chemical or material properties. The field is evolving as fast as the increase in computational power. The great shift towards computational experiments in the field is not surprising since they may reduce research costs by up to 90% — a welcome statistic during this financial crisis.

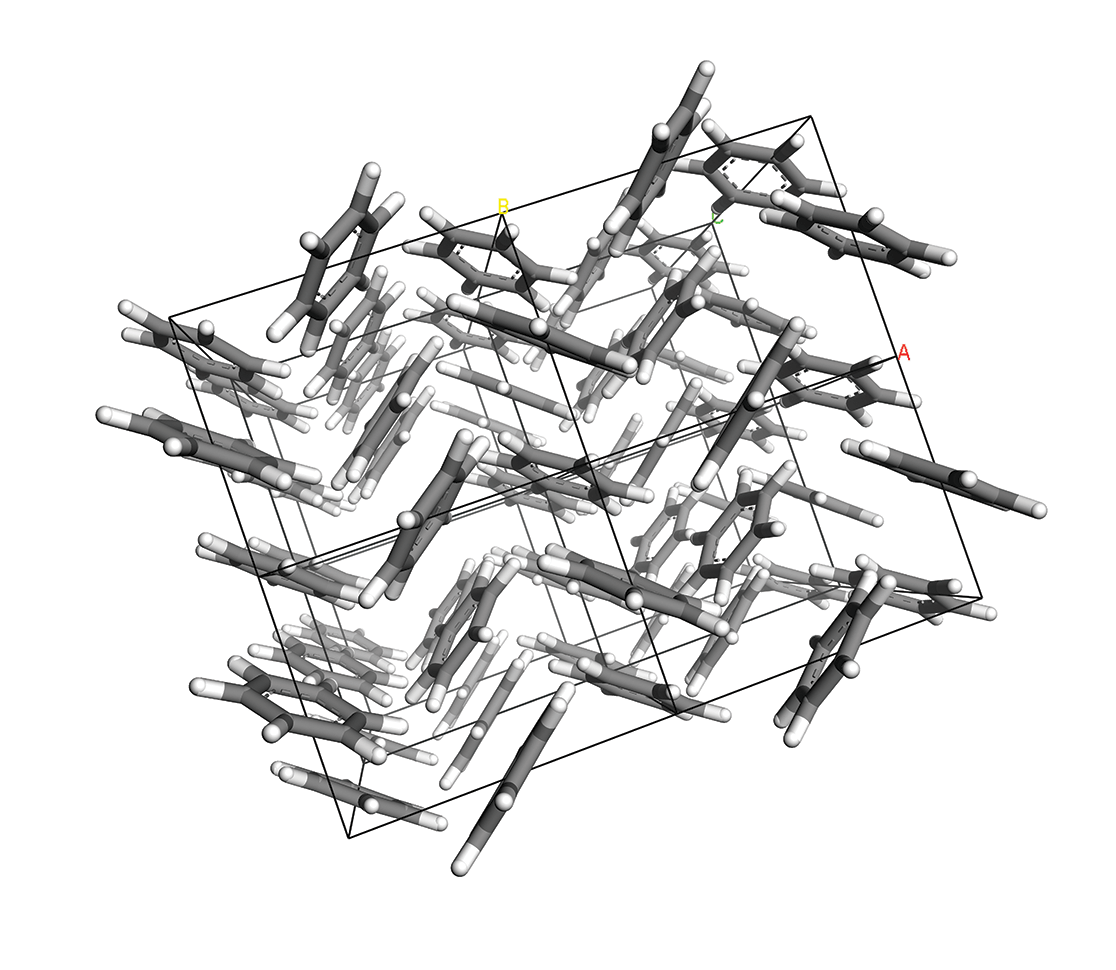

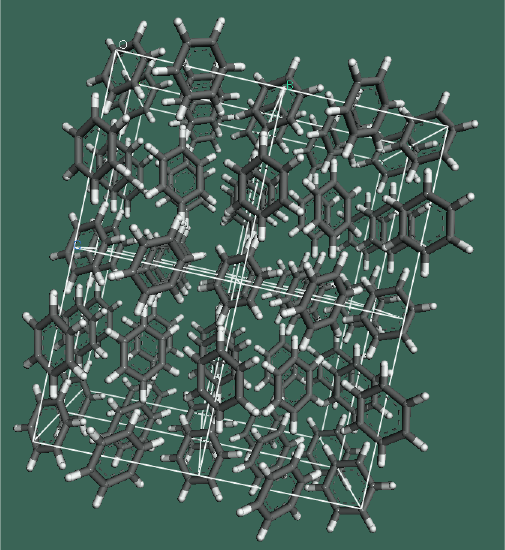

Keith M. Azzopardi (supervised by Dr Daphne Attard) used two distinct computational techniques to uncover the structure of a carcinogenic chemical called solid state benzene. He also looked into its mechanical properties, especially its auxetic capability, materials that become thicker when stretched. By studying benzene, Azzopardi is testing the approach to see if it can work. Many natural products incorporate the benzene ring, even though they are not toxic.

The crystalline structures of solid state benzene were reproduced using computer modelling. The first technique used the ab initio method, that uses the actual physical equations of each atom involved. This approach is intense for both the computer and the researcher. It showed that four of the seven phases of benzene could be auxetic.

The second less intensive technique is known as molecular mechanics. To simplify matters it assumes that atoms are made of balls and the bonds in between sticks. It makes the process much faster but may be unreliable on its own due to some major assumptions. For modelling benzene, molecular mechanics was insufficient.

Taken together, the results show that molecular mechanics could be a useful, quick starting point, which needs further improvement through the ab intio method.

This research was performed as part of a Masters of Science in Metamaterials at the Faculty of Science. It is partially funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). This Scholarship is part-financed by the European Union – European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II –Cohesion Policy 2007-2013, “Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality Of Life”. It was carried out using computational facilities (ALBERT, the University’s supercomputer) procured through the European Regional Development Fund, Project ERDF-080 ‘A Supercomputing Laboratory for the University of Malta’.

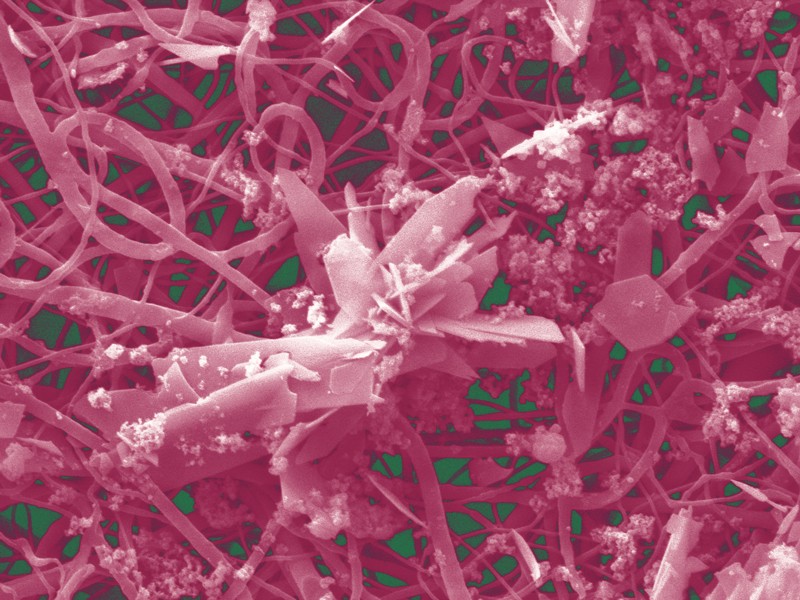

Scientific beauty of diamonds

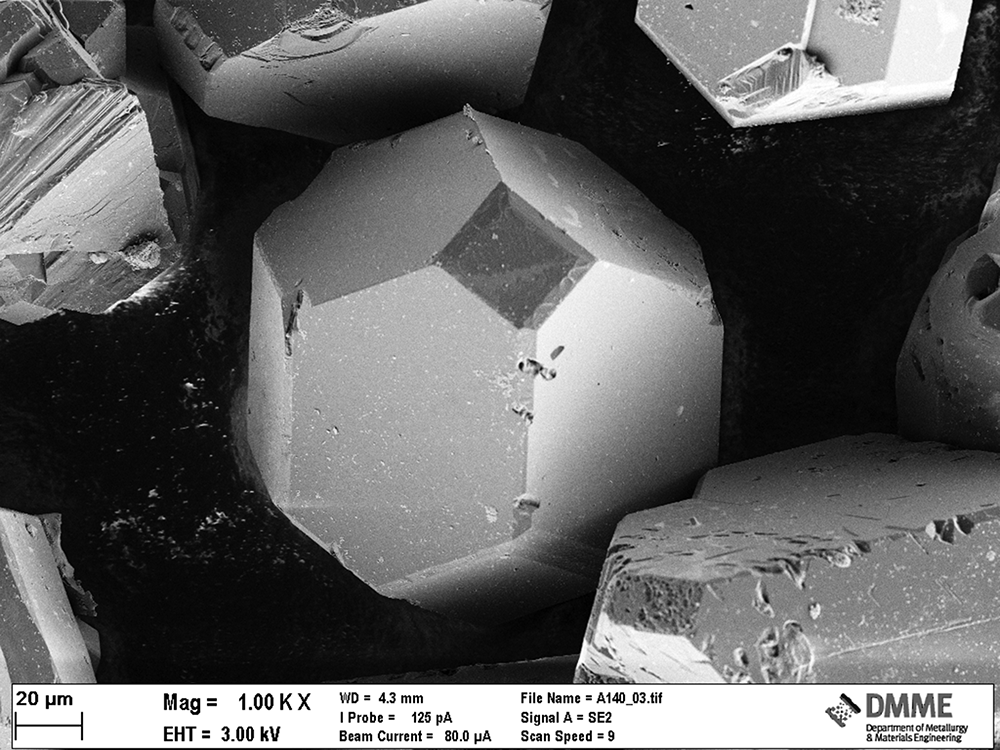

Laptops and mobiles are smaller, thinner, and more powerful than ever. The drawback is heat, since computing power comes hand in hand with temperature. Macs have been known to melt down, catch fire and fry eggs — PCs can be even more entertaining. David Grech (supervised by Prof. Emmanuel Sinagra and Dr Ing. Stephen Abela) has now produced diamond–metal matrix composites that can remove waste heat efficiently.

Diamonds are not only beautiful but have some remarkable properties. They are very hard, can withstand extreme conditions, and even transfer heat energy faster than any metals. This ability makes diamonds ideal as heat sinks and spreaders.

The gems are inflexible making them difficult to mould into the complex shapes demanded by the microelectronics industry. By linking diamonds with other materials, new architectures can be constructed. Grech squashed synthetic diamond and silver powders together at the metal’s melting point. The resulting composite material expanded very slowly when heated. The material could dissipate heat effectively, and was cheaper and simpler to produce than current methods — a step closer to use on microchips.

Grech’s current research is focused on obtaining novel types of interfaces between the diamond powders and the metal matrix. The new materials can improve the performance of heat sinks. New production techniques could help make these materials. By depositing a very thin layer of nickel (200 nanometres thick) on diamond powders using a chemical reaction, the gems would form chemical bonds with the layer while the metal matrix would form metallic bonds. The material would transfer heat quickly and expand very slowly on heating. A heat sink made out of this material would give us a cooler microprocessor and powerful electronics that does not spontaneously catch fire — good news for tech lovers.

This research was performed as part of a Bachelor of Science (Hons) at the Faculty of Science. It is funded by the Malta Council for Science and Technology through the National Research and Innovation Programme (R&I 2010-25 Project DIACOM) and IMA Engineering Services Ltd.

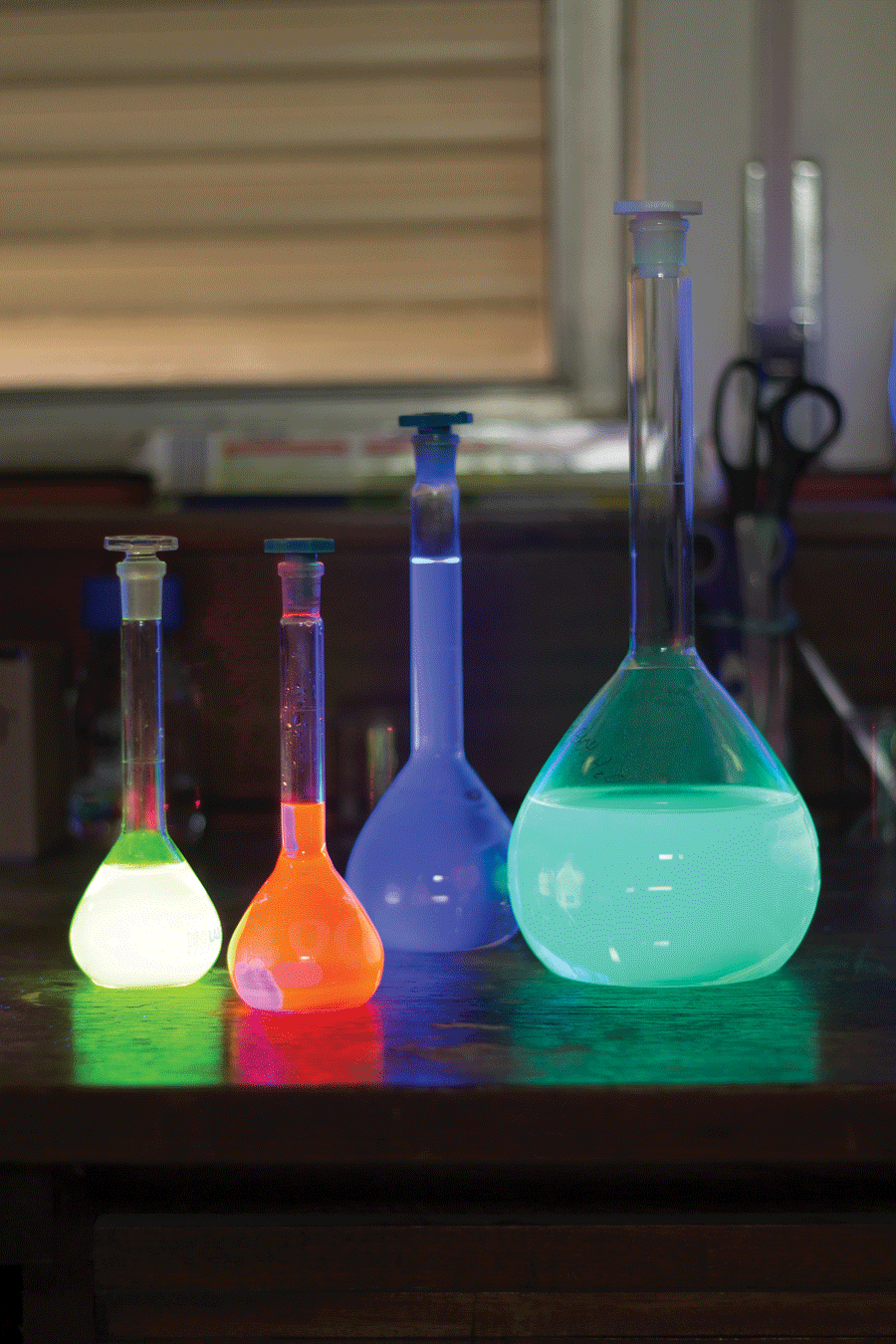

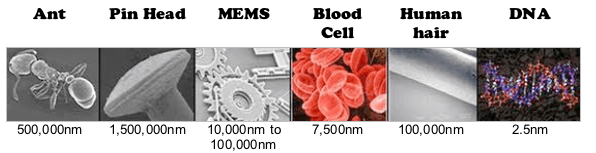

Labs in solution

Imagine the smallest thing you possibly can. The eye of a needle? A human hair? A particle of dust? Think smaller, something you cannot even see, something on a molecular scale. Now imagine that molecule has the potential of a whole laboratory. This dream is now becoming a reality.

In recent years, the field of molecular sensors has grown into one of the most ground-breaking areas in Chemistry. Molecular sensors are compounds that can detect a substance, or unique mixture of substances, and provide an easily detectable output. Usually this is a change in the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light, or in the emission of Fluorescence. In other words: colours!

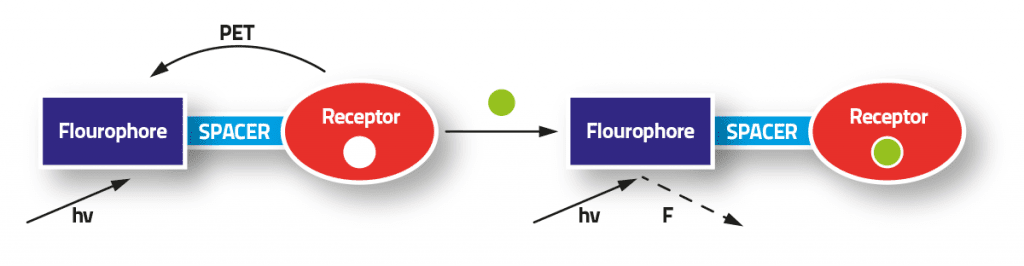

John Gabarretta (supervised by Dr David Magri) created a simple example of these fluorescent molecular sensors. The molecule was based on the Fluorophore-Spacer-Receptor model, where the ‘output’ part of the molecule (the fluorophore — a structure which shines light) is separated from the ‘input’ part (the receptor — a structure which is sensitive to a particular substance, such as acidity or a metal ion) by an intermediate spacer, whose main function is to link these two components together. The model means that a molecule can detect a chemical and respond by shining light or not. The process gives information about the chemicals in a solution.

The molecule was made by a two-step synthetic route (which took several attempts and resulted in several different colours), and its behaviour was tested by dipping into an acid. In water the molecule was switched ‘off’, but quickly turned ‘on’ in an acidic solution by giving a bright blue light when exposed to ultraviolet light (UV) — a pretty satisfying sight!

Molecular sensors have some very advanced applications — the pioneer A. P. de Silva said that there is room for a “small space odyssey with luminescent molecules”. This odyssey includes some that detect substances such as sugars.

While very advanced systems are approaching chemical computers, since they have multiple inputs and use Boolean Logic, the so-called ‘Moleculator’ or ‘gaming tic-tac-toe’ systems. The future is bright (if you pardon the pun) and with more complex structures more possibilities will appear; the molecular laboratory may become a reality detecting diseases or toxins in no time at all.

This research was performed as part of a Bachelor of Science (Honours) at the Faculty of Science.

Keeping heart attacks on hold

Heart attacks and strokes kill millions every year. Most are caused by blockages to blood vessels. Vessels can be pried open by heart stents, tubular devices that are inserted and inflated to prevent vessels from collapsing or blocking. Stents incur many problems ranging from flaring at the edges to fracturing to unexpected shrinking. All lead to complications, further surgery, and even death.

Luke Mizzi (supervised by Prof. Joseph N. Grima, Dr Daphne Attard, and Dr Ruben Gatt) has studied existing stent designs to identify their weaknesses and is currently studying novel designs that overcome these problems. He used computer simulations to replicate the stresses current stents experience in the human body. These stents performed well in response to inflation and bending. However, shortening still occurs and they do not expand uniformly leading to flaring at the edges.

Mizzi found which current designs fared well but no design had all the features needed by heart stents. Crowns with a zigzagging structure allow for high expandability while S-shaped connections between crowns allow for high flexibility.

Mizzi who forms part of the Metamaterials Unit is designing new stent geometries that build on these features incorporating them all and improving stent performance. The next step for these researchers are designs that support part of the throat or oesophagus to continue saving lives.

This research was performed as part of Doctoral Studies at the Faculty of Science at the University of Malta. It is funded by the Malta Council for Science and Technology through its R&I programme. This project is in collaboration between the University of Malta, HM RD Ltd, part of the HalMann Vella Group of Companies, and Tek-Moulds Precision Engineering Limited.

The Nanomolecular World

In life we are more capable of observing what we easily see. New technologies make it much easier to peek into the nano world to see molecules and atoms. By looking at the very small systems we can understand much larger ones.

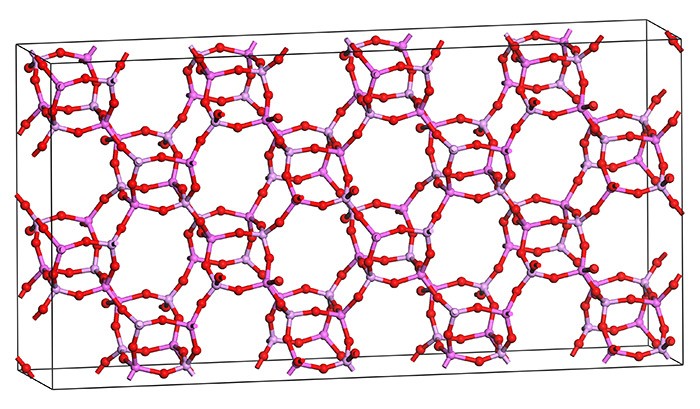

Dr Reuben Cauchi (supervised by Prof. Joseph N. Grima, Dept. of Chemistry and Metamaterials Unit) has studied the structural chemistry of particular inorganic crystals (zeolites) through various molecular modelling techniques to learn how nano features result in unusual properties. By using structural chemistry techniques, Cauchi also studied the mechanisms that influenced these unusual properties under different conditions of pressure and temperature. They resulted in some extremely useful properties.

Dr Cauchi observed multiple unusual properties in a single zeolite crystal. Such complex combinations gave birth to the idea that other systems apart from zeolites can have more than one property at the same time. Studying zeolites allowed

the team Cauchi is part of to develop smart systems. These systems can be controlled by changes to stimuli indirectly related to each other, which effect the response to other stimuli.

Zeolites are naturally found crystals and beautiful systems to learn from. Studying such structures may help us think of new ideas and ways for technology improvement. For example, some of Cauchi’s findings are now being used by the Metamaterials Unit to develop smart honeycomb-like systems which can improve heart stent designs or make superior skin grafts.

This research was performed as part of Doctoral Studies at the Faculty of Science at the University of Malta and with the help of Gdansk University of Technology. It is partially funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). The scholarship is part-financed by the European Union — European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II — Cohesion Policy 2007–2013, “Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality of Life”. The Metamaterials Unit also acknowledges the funds received from the Malta Council for Science and Technology through their R&I scheme.

Does Alcohol kill brain cells?

This myth is HUGE! Urban legend says that drinking kills cells, some even say: ‘three beers kill 10,000 brain cells.’ Thankfully, they are wrong.

In microbiology labs, a 70% alcohol 30% water mix is used to clean surfaces pretty efficiently. It seems our neurons are made of sturdier stuff.

Alcohol does affect brain cells. Everyone knows that and it isn’t pretty. Alcohol can damage dendrites, which are delicate neural extensions that usually convey signals to other neurons. Damaging them prevents information travelling from one neuron to another — a problem. Luckily, the damage isn’t permanent.