DNA is what life is made of. Found in every cell of the human body, it has sent criminals to jail and been the focus of controversial court cases. Dr Jean Buttigieg discusses these legal and ethical issues. DNA has also transformed the meaning of being human, with traits from disease to intelligence all linked to it. DNA is changing the world.

Octopus around Malta: Safe to eat?

Heavy metals can be toxic to humans. They need to be monitored to ensure environmental levels do not go above dangerous levels. The European Commission has set acceptable maximum levels of metals allowed in food since most metals end up in humans through their diet.

But how do metals find their way into our food in the first place? Heavy metals can enter the environment in a number of ways, including through volcanism, fossil fuel burning, and antifouling paint use. The heavy metals bind with biomolecules inside living tissue, and can build up to dangerous levels. One prime example of how such metals end up in the food we eat can be seen in the case of the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris). The octopus is susceptible to accumulating high levels of heavy metals due to its high ingestion rate of benthic fauna.

Joshua Gili (supervised by Prof. Victor Axiak) recorded the concentrations of cadmium, copper, lead, and zinc in the common octopus. Specimens were collected from around Malta during summer and winter. The analysis was performed on two of the species’ tissues—the tentacles and the digestive glands— which function in a similar way to the human liver. Each tissue was gathered into one pool by site, then homogenised, dried, and acid-treated. Afterwards a technique called polarography was used to determine the levels of each metal. This data helped Gili decide whether metal accumulation in the tissue of octopi is affected by biometry, season, or geography.

In Malta, metal levels depended on where the octopus was caught. In general, the concentrations were lower than other Mediterranean regions. The levels of cadmium and lead in the tentacles were below toxic levels as stated by the European Commission, indicating that local octopus is safe to eat.

This research was performed as part of Joshua Gili’s Bachelor of Science (Honours) in Biology and Chemistry, which he is reading at the Faculty of Science, University of Malta.

Blood, Genes, and You

Over the course of nine months, an entire human body is sculpted from a few cells into a baby. The blueprint is the information written into our DNA. But what happens if there is a mistake in these blueprints? Decades worth of research carried out in Malta and abroad have aimed to understand how these errors lead to a disease common in Malta and prevalent worldwide.

Scott Wilcockson talks to Dr Joseph Borg (Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Malta) to find out more.

Time, Space, & the Ocean Wanders

As an archipelago, the Maltese Islands have been a hotspot for seabird nesting since time immemorial. Marie Claire Gatt talks about her research and a major EU project determining how to protect far travelling seabirds. Photography by Jean Claude Vancell.

Who owns you?

One fifth of human genes have already been claimed as US Intellectual Property. But should anyone own our genes? And what happens when gene ownership can drastically prevent the advancement of life-saving cures?

The US Patent Office’s most controversial patents are on BRCA1 and BRCA2, both linked to the high risks of ovarian and breast cancer. They are now owned by Myriad Genetic Laboratories. In 1996, Myriad Genetics developed and began marketing a predictive test for the presence of possible cancer-causing mutations: the ‘BRCAnalysis’ test. The price of the test was US$3,000 but the company promised that it would eventually drop the price to US$300. This never happened because its patent holder had the right to stop any other party from duplicating the patented sequences. This single test accounted for over 80% of Myriad Genetics’ multibillion dollar business.

In 2009, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) decided to challenge the patenting of human genes on legal grounds. The ACLU was the representative of 20 medial organisations, geneticists, women’s health groups, and patients unable to be screened due to the prohibitive patents. The ACLU’s position was that Myriad’s patents violated the patent law on the issue of patent-eligibility.

The case went before the Supreme Court. By 3 June, 2013 it was declared that the Myriad patents were invalid because they did not create or alter any of the genetic information encoded in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. The location and order of the nucleotides existed in nature before Myriad found them. The company simply discovered what was already there and did not create anything new.

There is no worldwide consensus on whether parts of the human genome should be granted intellectual property protection. The Myriad patents should alert us to the injustice of having a pharmaceutical company make money out of cancer predictive tests that could cost 10 times less than what is charged. The same patents stifled diagnostic testing and research that could have led to cures as well as limiting women’s options regarding their medical care in Malta as in all other parts of the world. There are various international and regional agreements that have described the human genome as being part of humanity’s ‘common heritage’, including the 1998 UN Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights. The Myriad patents controversy has shown that gene patenting does not work to stimulate more research—one of the prime arguments Big Pharma uses. It is time to explore other avenues that will both promote scientific progress and technological development but at the same time protect the special nature of human genes that make us who we are. No one should own our genes—they should be exploited in the interest of everyone.

Written by: Dr Jean Buttigieg

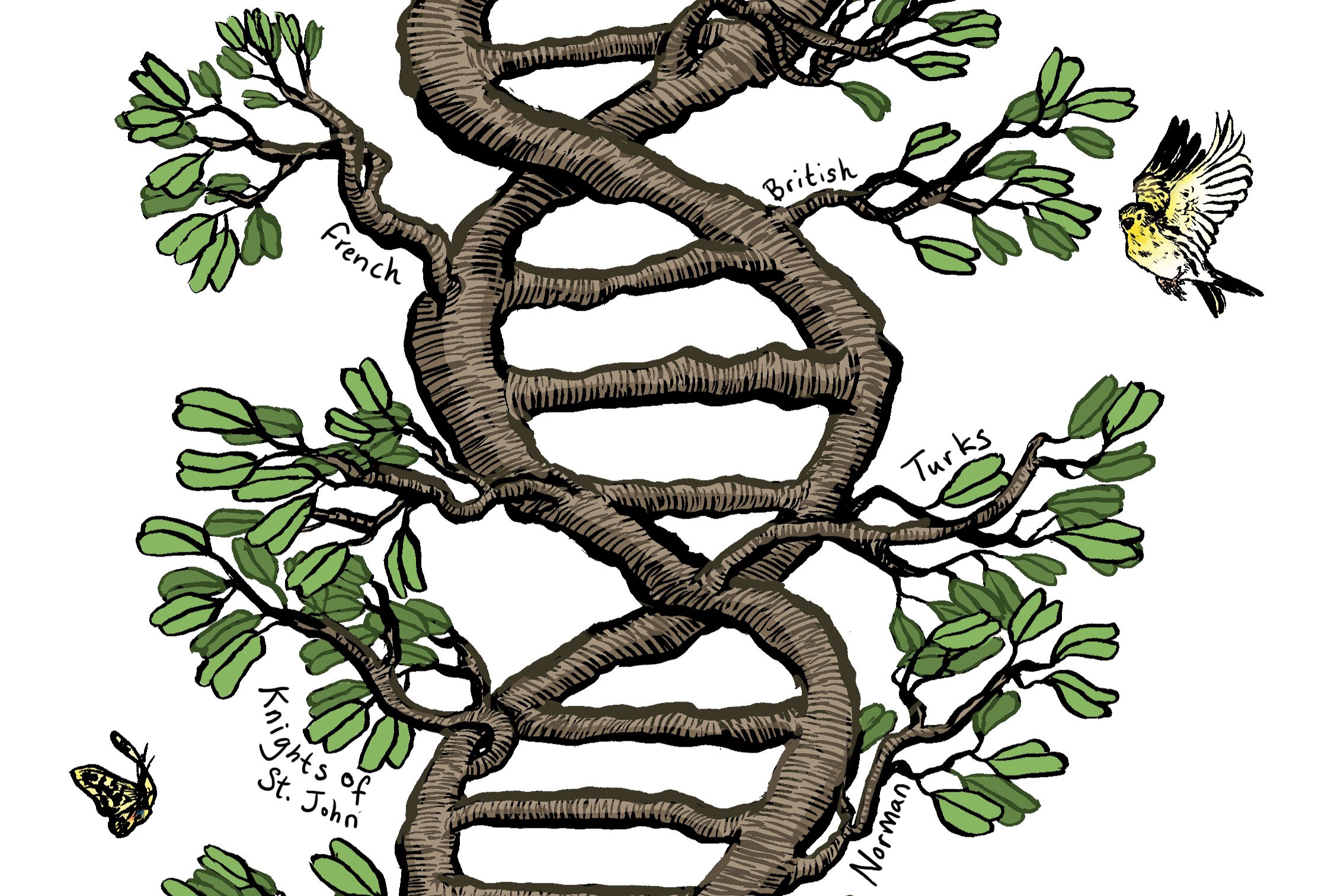

The Hidden History of the Maltese Genome

By reading someone’s DNA one can tell how likely they are to develop a disease or whether they are related to the person sitting next to them. By reading a nation’s DNA one can understand why a population is more likely to develop a disease or how a population came to exist. Scott Wilcockson talks to Prof. Alex Felice, Dr Joseph Borg, and Clint Mizzi (University of Malta) about their latest project that aims to sequence the Maltese genome and what it might reveal about the origins and health of the Maltese people.

What is More Addictive: Cannabis or Coffee?

The answer is coffee. Coffee is drunk by around 80% of Americans. The large numbers call for extensive studies on the effect of this drug on the brain.

Caffeine is a stimulant. It has a similar molecular structure to adenosine, a chemical linked to us feeling tired. Caffeine binds to adenosine and stops it from working. Coffee does not wake you up but makes your body forget it is tired.

Taking that espresso in the morning makes your body increase the number of receptors to caffeine in the brain. This increase makes us dependent on that cup of coffee in the morning to reach normal functional levels. On the other hand, cannabis has minimal risk of long-term addiction.

Send in your science questions to think@um.edu.mt

Heartbreakers

Every person possesses the same genes within every cell. Their DNA provides the information to first create an entire functioning body and then keep it running. While all humans share more than 99.9% of their DNA, it is the subtle differences in our DNA that ensure individuality. Many differences are superficial effects, like hair colour, but some can have disastrous health effects. Scott Wilcockson talks to Dr Stephanie Bezzina-Wettinger (Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Malta) about her research on these subtle differences and how they can contribute to heart attacks.

Rockets that Fail Safely

Spacecraft failures are spectacular. These unfortunate events are seared into the public memory. One reason why rockets can fail are software bugs. If a rocket’s computer system fails, that infamous blue screen leads to lost work hours, billions of Euro, and lives. Researchers from the Faculty of ICT and Faculty of Engineering (University of Malta) tell THINK about their collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA) to test novel satellite software architecture to prevent rocket failure.

Sensory Apparatus

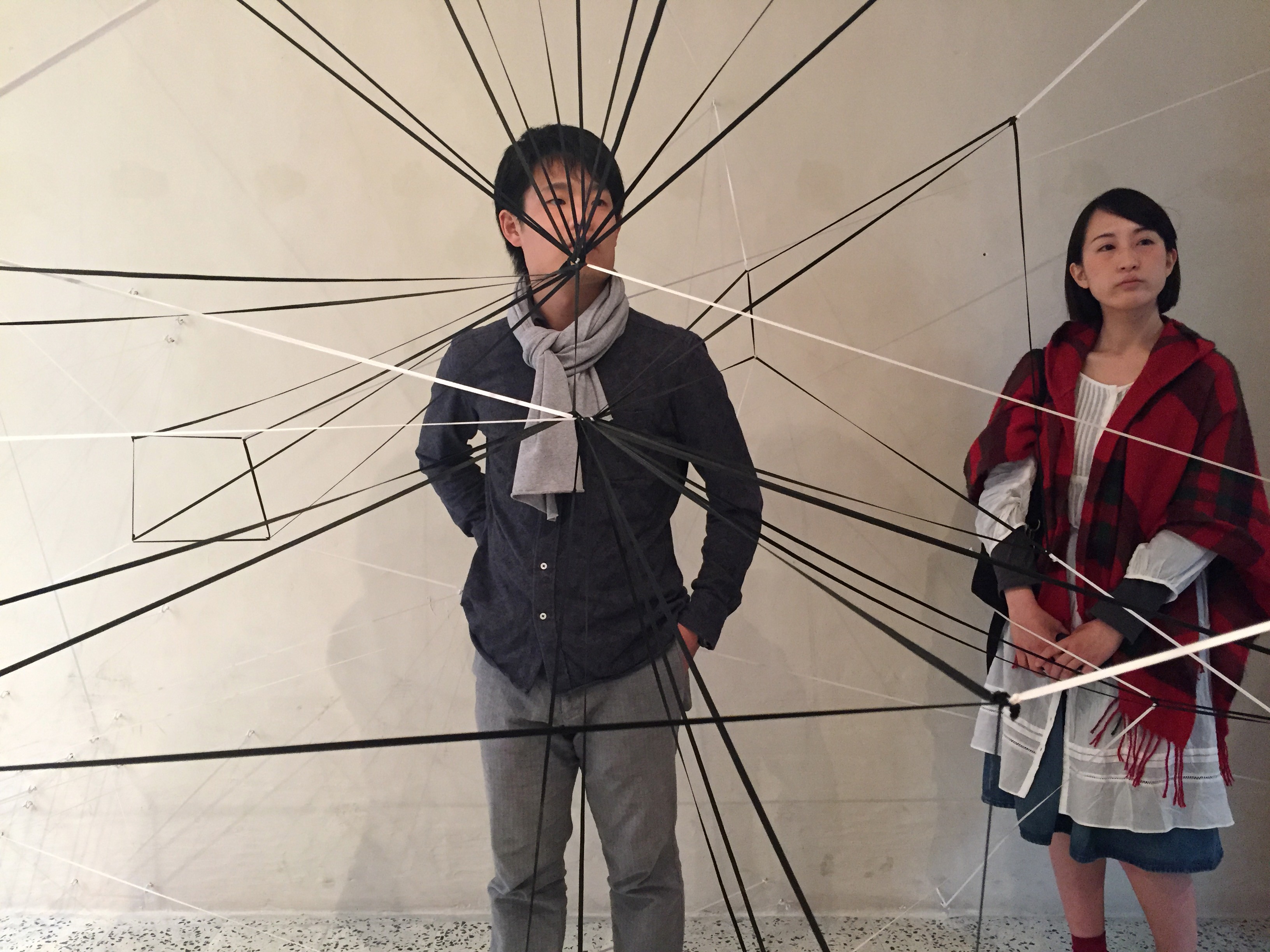

‘What does it really mean to sense something?’ That was the fundamental question Dr Libby Heaney (quantum physicist and artist) asked herself when she started working on Sensory Apparatus, currently on display at Blitz in Valletta. For almost a year she worked together with Bonamy Devas (artist and photographer) and Anna Ridler (designer working with information and data). For Libby sensing means the collection of data. Science tries to measure everything and is now through so-called ‘big data’ attempting to quantify subjective things, like happiness levels or the perfect online dating match.

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

The second room has circuit boards and speakers mounted to the walls. People curious enough will trigger a proximity sensor and a computerised voice starts talking. ‘Name. Country. Age. Address.’ What sounds like nonsense at first, quickly develops into the auditive representation of an algorithm. Passing consecutive speakers continuously reveals its different layers. These algorithms are complex programmes, designed to collect the footprints people leave while online. The information is used by marketers to direct and personalise adverts. ‘We wanted to reveal the technology. The actual objects represent the discussion we are trying to make.’

The last room is pitch black. Only when approaching the middle of the room a projector lights up, projecting advertisements directly onto people’s bodies. The commercial pieces, gathered from across Malta, follow every movement, change constantly and are reflected from the room’s glossy walls. At the exhibition opening, once people noticed they were being used as a billboard, they quickly moved away. ‘People change and behave differently in there’, Libby says, making it obvious how advertisements influence us online.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

The free exhibition opens every Tuesday–Thursday from 10am–3pm and Friday–Saturday from 3–7pm at Blitz, 68 St Lucia Street, Valletta, until April 6. For more information see thisisblitz.com

Sensory Apparatus is supported by Arts Council Malta / Malta Arts Fund.