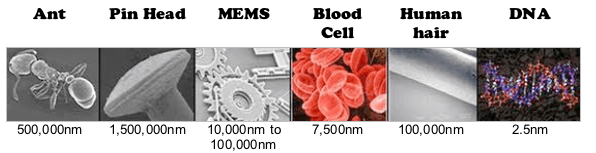

Computational chemistry is a powerful interdisciplinary field where traditional chemistry experiments are replaced by computer simulations. They make use of the underlying physics to calculate chemical or material properties. The field is evolving as fast as the increase in computational power. The great shift towards computational experiments in the field is not surprising since they may reduce research costs by up to 90% — a welcome statistic during this financial crisis.

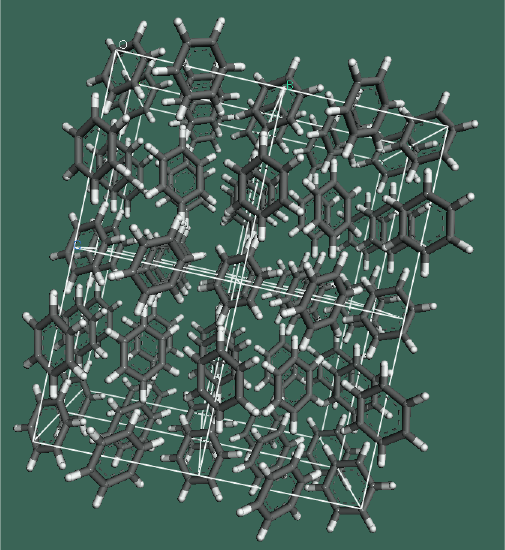

Keith M. Azzopardi (supervised by Dr Daphne Attard) used two distinct computational techniques to uncover the structure of a carcinogenic chemical called solid state benzene. He also looked into its mechanical properties, especially its auxetic capability, materials that become thicker when stretched. By studying benzene, Azzopardi is testing the approach to see if it can work. Many natural products incorporate the benzene ring, even though they are not toxic.

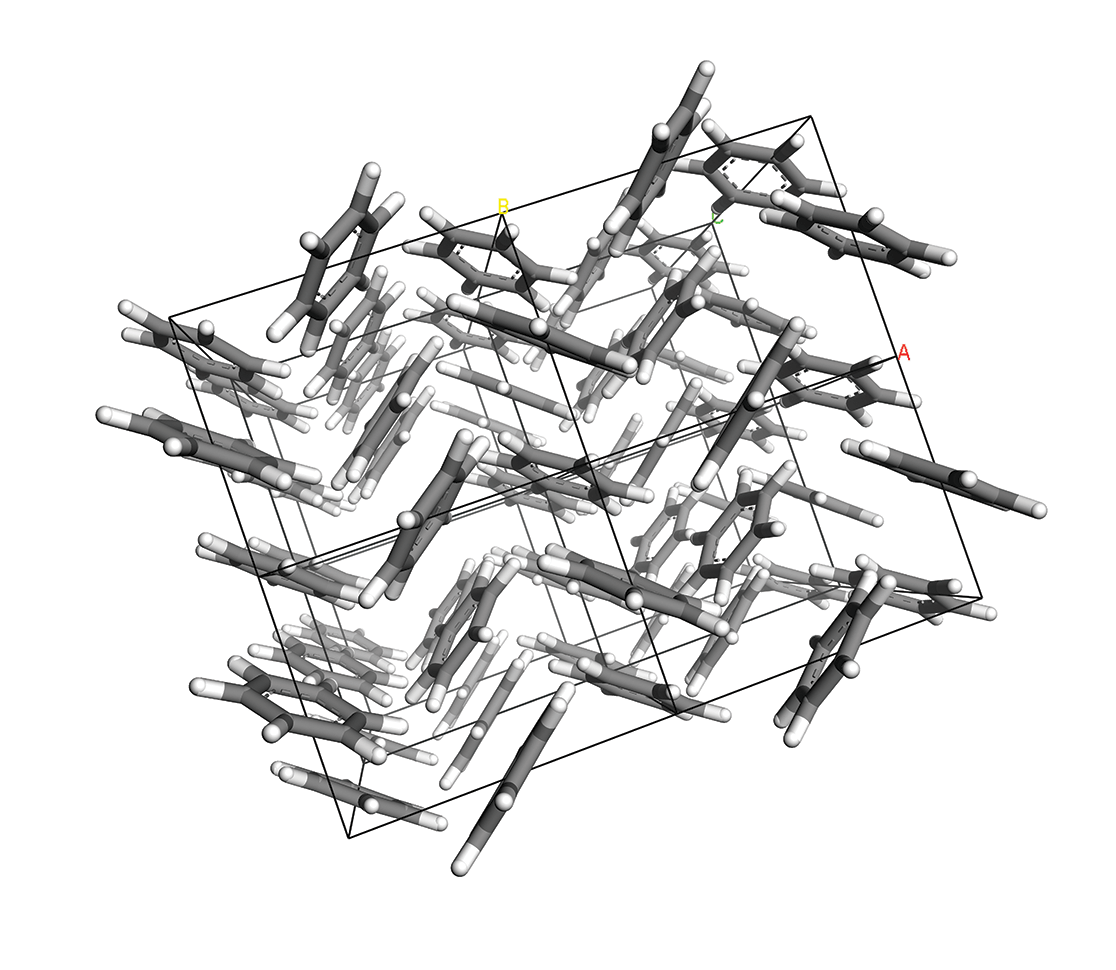

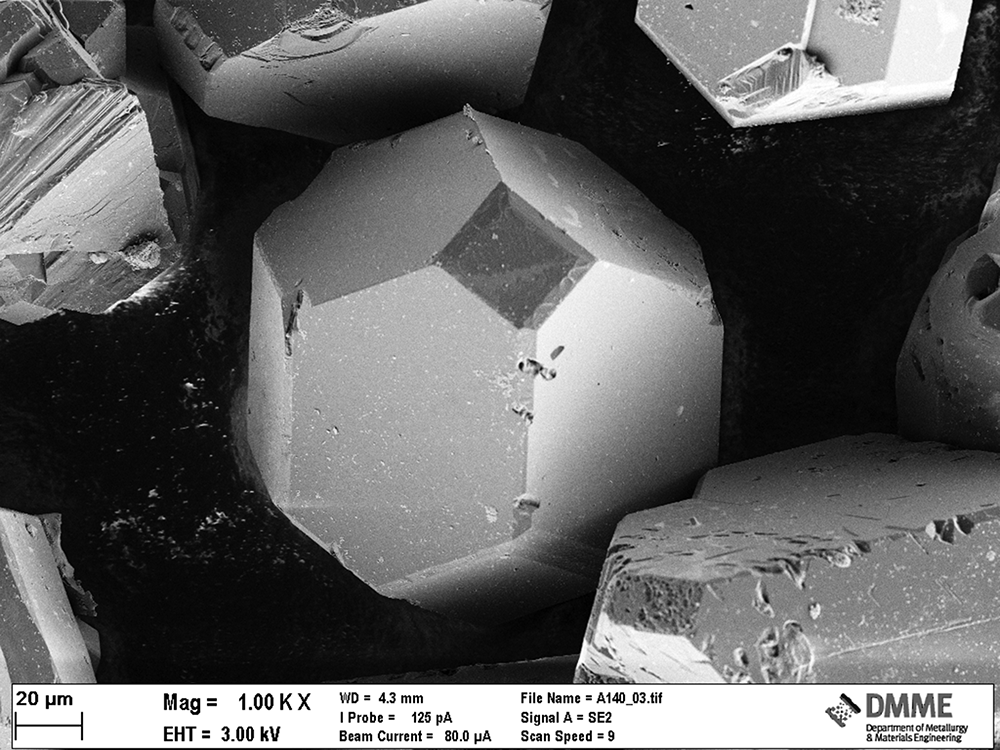

The crystalline structures of solid state benzene were reproduced using computer modelling. The first technique used the ab initio method, that uses the actual physical equations of each atom involved. This approach is intense for both the computer and the researcher. It showed that four of the seven phases of benzene could be auxetic.

The second less intensive technique is known as molecular mechanics. To simplify matters it assumes that atoms are made of balls and the bonds in between sticks. It makes the process much faster but may be unreliable on its own due to some major assumptions. For modelling benzene, molecular mechanics was insufficient.

Taken together, the results show that molecular mechanics could be a useful, quick starting point, which needs further improvement through the ab intio method.

This research was performed as part of a Masters of Science in Metamaterials at the Faculty of Science. It is partially funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). This Scholarship is part-financed by the European Union – European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II –Cohesion Policy 2007-2013, “Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality Of Life”. It was carried out using computational facilities (ALBERT, the University’s supercomputer) procured through the European Regional Development Fund, Project ERDF-080 ‘A Supercomputing Laboratory for the University of Malta’.