Malta’s brightest exports: Travelling to the EU’s JRC

A group of Maltese researchers travel to the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre site in Ispra to share their work in the fields of climate change, environment, and medicine. Cassi Camilleri writes.

Striving for Scientific Excellence

Research is a complex endeavour. From funding, to project management, quality assurance, and so much more, any active project, whether for applied or fundamental research, needs to tick a whole list of boxes for it to achieve its full potential. This is where we, the Research Support Services Directorate (RSSD), come in.

Our goal is to provide researchers with comprehensive support towards achieving scientific excellence, from identifying and advising on funding opportunities to getting specific accreditation of their scientific methods. And our newly established directorate reflects the growing ambition of the University of Malta (UM) to develop into a world-class research institution. We are a team of nine enthusiastic individuals with very diverse backgrounds.

Having worked and studied (apart from the UM) in institutes such as the University of Cambridge, Max Planck Institute, Imperial College London, University College London, University of Nottingham, the European Institutions, as well as the private companies like GlaxoSmithKline, Teva (Actavis), Novartis and Methode Electronics, our team is excited to bring international and private sector experience to the UM.

How can RSSD help you?

The most attractive funding opportunities for scientists at the UM nowadays are based on competitive European Union instruments. Preparation for them is intense, and only the most innovative and ground breaking ideas hit the mark. Our team can guide you not only to identify the most suitable funding opportunity, but also on building the right team, all the while ensuring that strict EU guidelines are being followed. We also help you identify and approach collaborators in Academia, private industry, and the state—a requisite of many EU funding programmes. To this end, RSSD aims to be the interface between the academics, researchers, and the general administration, as a one-stop shop for research funding. Once the project is successful and funded, we will then link it with the range of support services available. But that is not where our contribution ends.

On the laboratory and infrastructural side of RSSD, we help the scientific, technical, and laboratory staff at the UM to bring experimental laboratories to a world class level. The multifaceted nature of this work makes it difficult to summarise. Among other things, it involves building services, laboratory output, systems design and commissioning, followed by quality assurance, such as managing standard operating procedures (SOPs) and supporting and writing equipment tenders, creating and managing asset databases, and ensuring proper waste management. We can also contribute to managing your projects, all in the bid to improve the efficiency, productivity, and function of any laboratory.

The next step in this chain of quality assurance is obtaining accreditation for some of the techniques and methods used. To this end, accreditation and SOPs ensure reliable, repeatable, and reproducible measurements, a must for work in and with the private sector.

RSSD will give you the right support needed to achieve your vision.

How to get in touch?

We are based on the first floor in the Regional Building, Triq l-Imħallef Paolo Debono, or simply drop us an email on rssd@um.edu.mt or visit our website at um.edu.mt/rssd

Where Humanities, Medicine, and Sciences meet

Not many Ph.D.s lead to a new programme of studies, but cardiac paediatrician Prof. Victor Grech’s did. His study on Infertility in Science Fiction inspired him and his supervisors, Prof. Ivan Callus and Prof. Clare Vassallo, (University of Malta) to start the HUMS programme: a space for researchers in the humanities, medicine, and sciences to meet and discuss the bridges between these areas.Continue reading

Look up↑

Earth is just one planet in a solar system that wanders around a galaxy. Each galaxy is unique in its own right, each composed of its special ration of dust, gas, and endless stars. What unites them all is the mysterious dark sky that they float in: the Universe.

A constantly growing expanse of space and time, the Universe’s attractive gravitational force is currently decreasing while its repulsive force is increasing. This repulsive force is referred to as dark energy. It is pushing galaxies apart at an increasing rate, bringing up a flurry of questions. Why is this happening? How does dark energy work? What is the role of magnetism?

To answer these questions and more requires the right tools. Improvements in instrumentation up until now have enabled astronomers to unveil many mysteries, not only in the visible region of our Universe where human eyes are sensitive to electromagnetic waves, but also beyond. This is done through various means. Optical telescopes, such as the famous Hubble Space Telescope, detect the intensity of incoming radiation in the optical band of the spectrum. Fundamentally, all celestial objects emit electromagnetic radiation, among them radio waves.

The observation of cosmic objects in these radio frequencies is defined as radio astronomy. Because radio waves penetrate dust, scientists utilise radio astronomy techniques to explore undetectable areas of space which cannot be seen using visible light by optical telescopes.

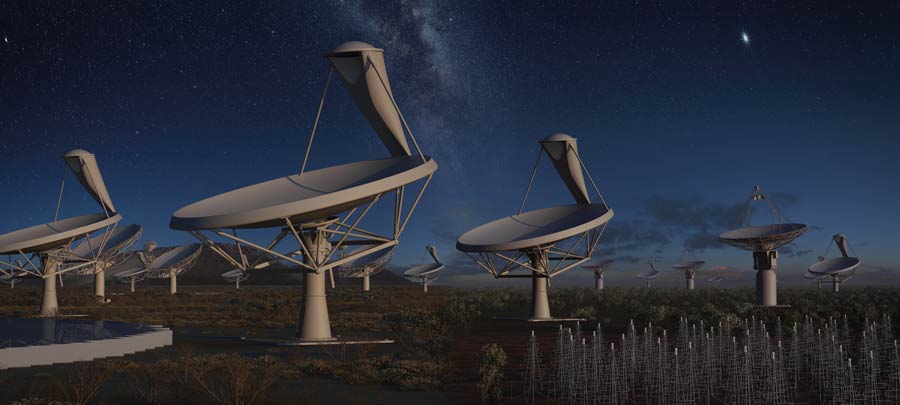

The project is an international effort to build the world’s largest multi radio telescope that will have a total collecting area of approximately one million square metres.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project is the largest project planned for the 21st century. It will see thousands of radio telescopes built in South Africa and Australia. It will enable unparalleled insights into the Universe. The project is an international effort to build the world’s largest multi radio telescope that will have a total collecting area of approximately one million square metres. SKA’s developers are building a system that would operate over a wide range of frequencies, and its size would make it 50 times more sensitive than any other radio instrument. It is set to be able to take images of the sky at up to 10,000 times the speed of current survey radio telescopes.

The University of Malta’s (UoM) contribution to the SKA project is being spearheaded by the Institute of Space Sciences and Astronomy (ISSA). ISSA Founder Prof. Kristian Zarb Adami, Faculty of Science Dean Prof. Charles Sammut, and Iman Farhat are developing an antenna which can be printed like a newspaper and can be rolled out like a carpet.

Unlike conventional antennas which are designed to work optimally at one frequency, the engineering prototype developed at the UoM can sense a large range of frequencies and is capable of running applications such as TV, wireless, Bluetooth, and near-field communications. This was also important because ISSA researchers are trying to detect the first atoms and molecules that were formed at the earliest stages of the Universe. This antenna is also intended to serve as a cost-effective element to cover remote locations for SKA.

The SKA project is scheduled to be built in phases, starting in 2018 and finishing in 2024. Even before the SKA is online, several thousand combined radio telescopes will be collecting and processing data equivalent to 100 times today’s global internet traffic per [unit of time].

The first small scale prototype antenna ISSA built had 256 elements and met SKA’s application and requirements. This was immensely motivating, especially when considering the high standards of this world-wide consortium. The initial success drove home the possibility of further in-depth studies.

ISSA has now embarked on building a large-scale version of the array (funded by the Technology Development Programme of the Malta Council for Science and Technology and Malta Communications Authority). The Malta array demonstrator is an implementation of two antenna arrays. Each array consists of 5,000 elements covering an area of 100 m2. The main aim of this is to test the array in an environment close to its real world conditions. The characterisation of the antenna array radiation pattern is being investigated using a far-field flying source. The system makes use of drones equipped with a transmitter and a dipole antenna that communicates with the array on test. The team is now working on this antenna to ensure a seamless performance.

SKA is a behemoth of a project, involving about 100 organisations across 20 countries. With it, scientists and researchers all over the world will be able to conduct transformational science in astronomical observation, breaking new ground with every step and redefining our understanding of space as we know it.

Key goals include challenging Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to have a closer look at how the very first stars and galaxies formed moments after the Big Bang. It could also potentially provide an answer to one of the greatest mysteries known to humankind—are we alone in the Universe?

Why write?

By Prof Victor Grech

All academics are constantly encouraged to share their research with the world through journals. Furthering knowledge is the aim, providing colleagues far and wide with a building block on which to potentially further their own work. But are these noble motivations what really drive researchers to publish? According to a study by Bryan Coles (1993), the short answer is no.

It has been shown that authors in the sciences publish primarily to disseminate their own work (54%). Other reasons are the furthering of career prospects (20%), improving funding opportunities (13%), ego (9%), and patent protection (4%).

Clearly, there are huge personal motivations to publish, and with good reason. Globalisation has seen job competition rocket. Today, finding a job opening is hard enough, let alone climbing the career ladder. The term ‘publish or perish’ takes on a more threatening and terrifying overtone as this is now literal and no longer a metaphor.

Careers depend on publishing.I research is conducted without being written up as a paper and accepted in a reputable journal, then it is almost as if it has simply not been done at all. It has not been given official public recognition. Not only this, but even if one has a worthwhile research project to investigate and write up, there are many intervening steps that must be negotiated before a paper can be completed; from drafting a proposal for ethics and data protection, to opting co-authors, all the way to dealing with rejections, editors, and resubmissions, the road to publication is a rocky one.

Understandably, the process can be daunting for many. Thankfully, there are people and courses specifically tailored to help researchers with this. How to Write a Scientific Paper (WASP) is one of them: this is a three-day intensive course being held in London at the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, with formal lectures and interactive sessions that will help researchers not only start their journey to publishing, but also see it through.

The organisers are also tentatively planning to hold another of these courses in Malta in 2017.

For more information, visit the Maltime website and the event on Facebook.

Analysing Alice: Finding order in chaos

With every particle collision in the ALICE experiment, a terabyte of data per second is generated for analysis. But not all of it is essential information. David Reuben Grech speaks to Dr Gianluca Valentino and Dr Johann A. Briffa about their work in separating the wheat from the chaff and removing noise from two of ALICE’s 18 subdetectors.

Curious matters

Society is built on curiosity; the drive to find answers to life’s abounding questions. This curiosity continues to fuel our brightest minds today. Cassi Camilleri talks to ALICE experiment leader Prof. Paolo Giubellino about his work at CERN and how it impacts our daily lives.

Initiating Alice

A magnificent feat of engineering, the LHC goes where no other machine has gone before.

Continue reading