Pushing for Malta’s industrial renaissance

With all the cranes strewn across the Maltese landscape, it appears that the construction industry is one of Malta’s primary economic drivers. But there are other, less polluting ways of generating income. Dr Ing. Marc Anthony Azzopardi discusses MEMENTO, the high-performance electronics project that could pave the way for a much-needed cultural shift in manufacturing.

Continue readingCan the EU empower women in Afghanistan

The European Union’s success relies on positive relationships—cooperation and good will is key. The EU’s Development and Cooperation Policy exists to support these connections. Its focus is on external relations, establishing partnerships with developing countries and channelling billions of euros to them every year. The European Commission plays a crucial role in this regard, managing and implementing directives on behalf of the EU. But what do we really know about the effectiveness of EU aid in helping citizens in developing countries? And how far is female empowerment part of this agenda?

In short—we don’t know much!

Research in this area is scarce, and this is what prompted me to tackle this question myself, under the supervision of Dr Stefano Moncada. My specific focus was on assessing whether the EU is committed to gender equality and female empowerment, taking Afghanistan as a case study. I reviewed all the available aid programming documents from the last financial period, and assessed whether the EU was effectively supporting Afghanistan to achieve the fifth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of gender equality. I adopted a mixed-method approach, using content analysis and descriptive statistics. Basically, this meant coming up with a very long list of keywords related to gender, and checking how many times these words appeared in the policy documents. Whoever invented the ‘ctrl + F’ function saved my academic life!

The results of my research were pretty surprising. I found that the EU is now focusing much more on gender empowerment on the ground in Afghanistan than it did a few years ago.

According to my data, and when comparing this to previous studies, it appears that the EU’s commitment to supporting this goal is growing over time. However, I also found that there is substantial room for improvement, as the attention given to such issues is rather conservative, and not equally balanced across all the SDG targets. For example, the need to increase women’s employment is mentioned many more times than the need to support female education or political participation. This is surprising as education is key to many other improvements in wellbeing. Nevertheless, I believe the overall results are encouraging and important, not only to highlight improvements in the effectiveness of the EU’s development and cooperation policy, but also in reply to a growing sentiment that puts into question the EU’s capacity to manage, and lead, in key policy areas. We can only hope that this continues exponentially.

This research was carried out as part of a Bachelor of European Studies (Honours) at the Institute for European Studies, University of Malta. The dissertation received the ‘2018 Best Dissertation Award’.

Author: Rebecca Zammit

Finding the soul in the machine

Swiss artist, documentary filmmaker, and researcher Dr Adnan Hadzi has recently made Malta his home and can currently be found lecturing in interactive art at the University of Malta. He speaks to Teodor Reljic about how the information technology zeitgeist is spewing up some alarming developments, arguing that art may be our most appropriate bulwark against the onslaught of privacy invasion and the unsavoury aspects of artificial intelligence.

Continue readingUp, up and away!

How do aerospace research engineers test new cockpit technologies without having to actually fly a plane Answer: flight simulators. These machines give pilots and engineers a safe, controlled environment in which to practise their flying and test out new technologies. In 2016 the team at the Institute of Aerospace Technologies at the University of Malta (IAT) started work on its first-ever flight simulator—SARAH (Simulator for Avionics Research and Aircraft HMI). Its outer shell was already available, having been constructed a few years back by Prof Carmel Pulé. From there, the team built the flight deck hardware and simulation software, and installed all the wiring as well as side sticks, pedals, a Flight Control Unit (FCU) and a central pedestal. The team constructing the simulator faced many hurdles. The biggest challenge was coordinating amongst everyone involved in the build: students, suppliers, and academic and technical staff. Careful planning was crucial.

The result is a simulator representative of an Airbus aircraft. However, it can also be easily reconfigured to simulate other aircraft, making it ideal for research purposes and experimentation. The Instructor Operating Station (IOS) also makes it possible to select a departure airport and change weather conditions.

One of the first uses of SARAH was to conduct research on technology that enables pilots to interact with cockpit automation using touchscreen gestures and voice commands. This research was conducted as part of the TOUCH-FLIGHT 2 research and innovation project (read more about this in Issue 19).

Going beyond the original aim of SARAH being used for research purposes, the IAT is also using the technology to educate graduates and young children in the hope of sparking an interest in the field. Earlier this year, a group of secondary school students flew their own virtual planes under the guidance of a professional airline pilot.

Looking ahead, the IAT plans to incorporate more state-of-the-art equipment into SARAH to increase its capabilities and make the user experience even more realistic. There are also plans to build other simulators—including a full-motion flight simulator and an Air Traffic Control simulator—and to connect them together to simulate more complex scenarios involving pilots and air traffic controllers; a scenario that would more closely resemble the experience of a real airport.Project TOUCH-FLIGHT 2 was financed by the Malta Council for Science & Technology, for and on behalf of the Foundation for Science and Technology, through the FUSION: R&I Technology Development Programme.

Author: Abigail Galea

Come ‘Here’!

A pointed index finger can mean many things. It can direct our attention to something, show us which way to go, or demand silence. It all depends on context—the situation in which it is used. This is what philosophers refer to as ‘indexicality’. And yes, you guessed it, the word ‘indexicality’ comes from the name of that particular finger.

At the University of Malta’s Institute of Digital Games, Prof. Stefano Gualeni has been playing around with this concept. Featuring the voice acting talents of independent game developers Emily Short and Pippin Barr, Gualeni has created a video game called Here, designed for players to engage with (and get confused by) the concept of indexicality.

Here’s gameplay poses the question of what it means when we say ‘here’ in a game world, and how many meanings of ‘here’ can exist side-by-side in a video game. It uses the trope from Japanese Role Playing Games of going on quests to retrieve bizarre items from classic locations. Spooky caves and castles are all part of the repertoire of locations that players can explore. But then, where do you go if ‘here’ is your instruction? What if ‘here’ isn’t where you think it is? What if you’re supposed to go upside down instead?

To try the game yourself, visit www.here.gua-le-ni.com

Author: Cassi Camilleri

Small islands, big research

Small island developing states are vulnerable and need unique solutions to overcome the hazards of climate change. Dr Stefano Moncada writes about research which tries to find the right answers to a complex problem.

Continue readingMaltese for all

What would you do if you were stripped of your words? If speech simply didn’t come to you? Sylvan Abela writes about MaltAAC, an Augmentative and Alternative Communication App for the Maltese Language.

Continue readingScience, dance, and Scotland

What if I told you that I could explain why the sky is blue through dance? All I would need is a fiddle player, a flautist, and a guitarist. By the end of it, we would all be dancing around like particles, hopefully with a better understanding of how the world around us works. This is exactly what neuroscientist and fiddle player Dr Lewis Hou does on a daily basis. Sitting through a boring science class with a teacher blabbing on about how important the information is might be a scene way too familiar for all of us. The science ceilidh (a traditional Scottish dance) aims to combat this misconception that science is all about memorising facts. Bringing people together to better understand and represent the processes within science through interpretative dance and other arts, the ceilidh has been proving a fruitful way of engaging people who would normally not be interested in science or research. ‘For us, that’s a really important guiding principle— reaching beyond those who usually engage,’ says Hou.

It all starts by bringing everyone together in one room. Researchers, musicians, and participants all get together. Researchers kick off the conversation by explaining what their work is and why it is relevant. Hou then helps the rest of the group break the scientific process down into its fundamental steps, be it photosynthesis, cell mitosis, or the lunar eclipse. The next step is translating each of the steps into a dance. And this is where everyone gets involved.

For us, that’s a really important guiding principle— reaching beyond those who usually engage.

Thinking back on how the idea came together, Hou says his first motivation to combine dance and science came when he was playing music and calling ceilidhs, all while attending as many science festivals as he could. ‘I realised there’s a big crossover with the spirit of folk music and dance—it’s all about participation and sharing. Everyone takes part even if they aren’t experts—and that is what we want to achieve in science communication. We want to encourage more people to feel able to participate without being scientists.’

‘Importantly, the nice thing about ceilidh dance is that they might be simple, but it also means that many people can join in and dance,’ emphasises Hou. Back in the studio, aft er having understood the science and its concepts, everyone works together to create the choreography. The science merges with their artistic interpretation. It is no longer something out of reach; it is now owned by everyone in the room.

Author: Abigail Galea

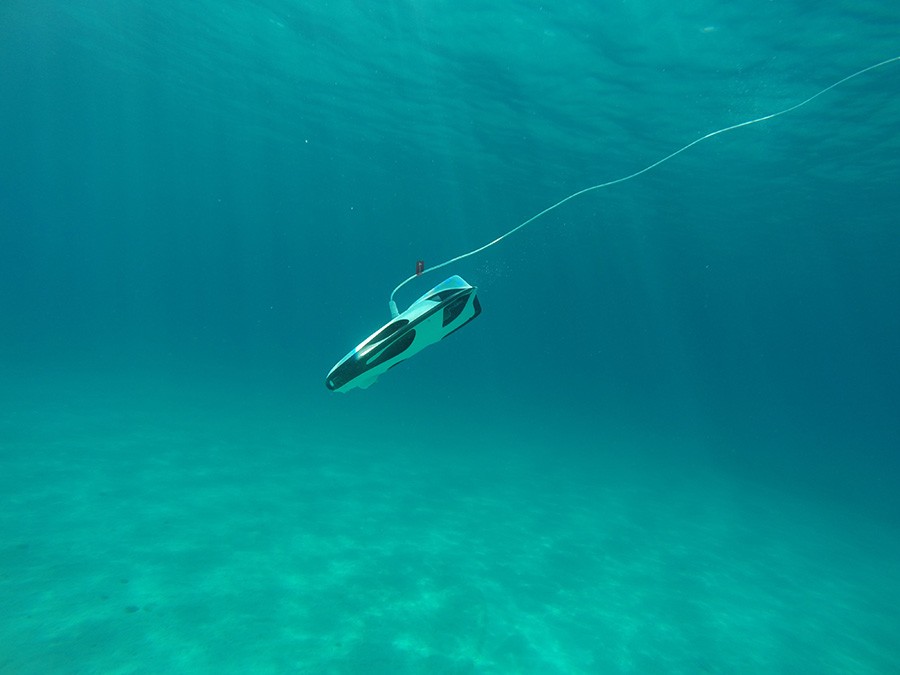

Underwater Eyes

Water covers 70% of Earth’s surface, but our oceans and seas might as well be alien planets. According to estimates, we’ve only explored about 5% of them so far. Crazy depths and dangerous conditions prevent humans from venturing into the unknown simply because we would be unable to survive. However, these limitations are being overcome. Drone technology can safely explore what lurks beneath the waves, and the Physical Oceanography Research Group from the Department of Geosciences at the University of Malta (UM) are doing just that.

Enter Powervision’s PowerRay Underwater Drone, an intelligent robot. It can capture real-time, high-res images beneath the sea’s surface. It has a wide-angle lens and instrumentation capable of determining temperature, sea depth, and even the presence of fish. Coupled with image processing and machine learning techniques being developed by the group, the drone maps the sea floor, determining its make-up as well as identifying locations where different fish species originate.

The small, lightweight drone can travel up to 1.5m/s and is currently being tested off the coast of Malta near Buġibba. This area has already been mapped manually by divers, which means that, when ready, the drone and human maps can be compared to evaluate the drone’s performance. If the AI algorithm produces accurate results, it will be used to charter unmapped regions—a first from Malta.

But its applications don’t end there. The drone can also be used to monitor the condition of other expensive marine instruments which spend a lot of time underwater. Without having to put on a diving suit, it allows the team to check on deployed water temperature sensors, tide gauges, and acoustic Doppler current profilers. This helps to optimise and plan maintenance, which in turn prolongs the hardware’s lifetime.

The UM team also want to use the technology to detect marine litter. They plan to identify litter ‘hotspots’ in order to raise awareness and organise clean-up campaigns—a valuable initiative to support vital efforts to clean up our oceans.