Emerging research suggests that mild sensory stimulation like touch can protect the brain if delivered within the first two hours following a stroke. Laura Bonnici speaks with experimental stroke specialist Prof. Mario Valentino to find out how uncovering the secrets of this ‘touch’ may have life-changing implications for stroke patients worldwide.

Stroke is universally devastating. Often hitting like a bolt from the blue, it is the world’s third leading cause of death. In Malta, over 10% of the deaths recorded in 2011 were due to stroke. But stroke inflicts suffering not only through a loved one’s passing. As the most common cause of severe disability, stroke can instantly rob a person of their independence and dignity—even their very personality. This impact, individually, socially, and globally, makes stroke research a top priority.

Yet while scientists know the risk factors, signs, symptoms, and causes of both main types of stroke—whether ischemic, in which clots stop blood flow to the brain, or haemorrhagic, where blood leaks into the brain tissue from ruptured vessels—they have yet to find a concrete solution.

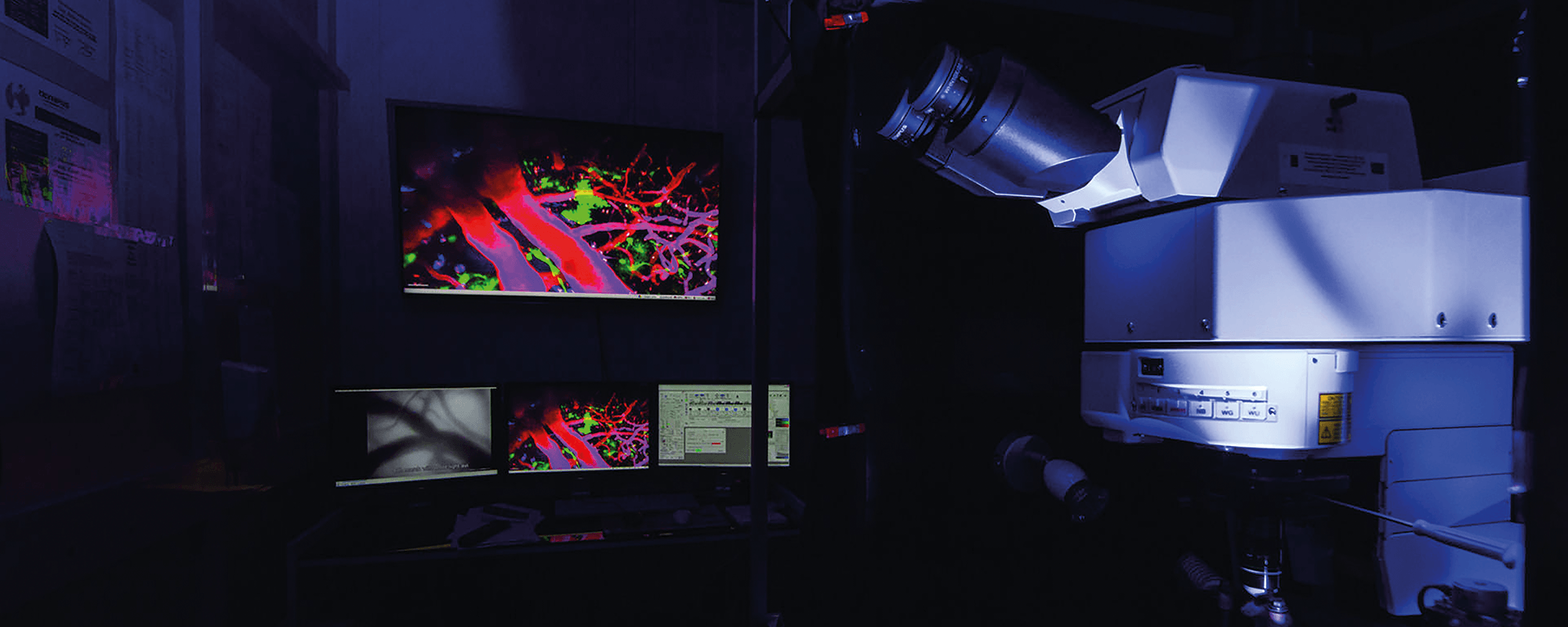

A dedicated team at the Faculty of Medicine (University of Malta) hopes to change that. Using highly sophisticated technology and advanced microscopic laser imaging techniques, Dr Jasmine Vella and Dr Christian Zammit, led by Prof. Mario Valentino, can follow what happens in a rodent’s brain as a stroke unfolds in real-time.

‘We use powerful lasers and very sensitive detectors coupled with special lenses, which allow us to capture the very fast events that unravel when a blood clot interrupts the blood supply in the brain,’ explains Valentino. ‘We observe what happens to the neighbouring blood vessels, nerve cells, and support cells, and the limb movements of the rodent throughout.’ Their aim is to find out how sensory stimulation might then help protect the brain.

The idea stems from an accidental discovery in 2010 by members of the Frostig Group at the University of Irvine, USA. The scientists found that when the whiskers of a rodent were stimulated within a critical time window following a stroke, its brain protected itself by permanently bypassing the blocked major artery that commonly causes stroke in humans. The brain’s cortical area is capable of extensive blood flow reorganisation when damaged, which can be brought about by sensory stimulation.

The human brain can bypass damage. For example, blind individuals have limited use of their visual cortex, so the auditory and somatosensory cortex expands, giving them heightened sensitivity to hearing and touch. For stroke patients, this means that the brain can compensate for its loss of function by boosting undamaged regions in response to light, touch, or sound stimulation.

‘This accidental discovery could be life-changing for stroke patients. The key is to figure out the mechanism involved in how sensory stimulation affects stroke patients, and then establish the best ways to activate that mechanism. Perhaps touching a stroke victim’s hands and face could have a similar beneficial effect, and this is what this latest research study hopes to define,’ says Valentino.

‘The team is now painstakingly correlating the data obtained during this brain imaging with the rodent’s movement and trajectory,’ he continues. ‘Using a motion-tracking device fitted under a sophisticated microscope, we can record the behaviour of the rodent during high-precision tactile stimulation, such as stroking their whiskers, and detect any gain of [brain] function through behavioural and locomotor readouts whilst ‘looking’ inside the brain in real-time.’

If they can prove that any protection is the direct cause of new blood vessels (or other cells) resulting from the electrical activity inspired by the sensory stimulation, then the next step would be to explore ways of redirecting these blood vessels to the affected brain area.

The team’s track record is encouraging. In collaboration with scientists from the University Peninsula Schools of Medicine and Dentistry, UK, they made another recent breakthrough that was published in Nature Communications, identifying a new drug, QNZ-46, that could protect the rodent brain following a stroke.

‘That project was about neuroprotective agents – to create a drug that will substantially block or reduce the injury, and so benefit a wider selection of patients,’ elaborates Valentino. ‘The study identified the source and activity of the neurotransmitter glutamate, which is the cause of the damage produced in stroke. This led to the discovery that QNZ-46 prevents some damage and protects against the toxic effects of the glutamate. This is potentially the first ever non-toxic drug that could prevent cell death during a stroke, and the results from this research could lead to pharmaceutical trials.’

While ongoing research in these projects has been supported through a €150,000 grant from The Alfred Mizzi Foundation through the RIDT, Valentino points out that globally-significant discoveries such as these are in constant need of support.

‘The funding of such projects is so important. This money is life-changing for people in such a predicament. Health research changes everything—our lifestyle, our quality of life, our longevity. And yet, government funding for research is still lacking. It’s only thanks to private companies and the RIDT, who realise the global potential of our work, that these projects can continue to try to change the lives of people all over the world,’ says Valentino.

And while Malta may be a small country with limited resources, the work conducted within its shores is reaching millions globally, proving that when it comes to knowledge, every contribution counts. We must continue striving for more to leave our best mark on the world.

Help us fund more projects like this, as well as research in all the faculties, by donating to RIDT.

Link: researchtrustmalta.eu/support-research/?#donations