Author: Clayton Axiak

Picture yourself waking up one morning with a severe, relentless itch that no clinician or diagnostic tool can understand. Your life would be thrown off kilter. Quality of life would suffer financially, psychologically, and socially as you try to look for a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. This is what life is like for most people living with a rare disease.

Often barraged with terms like ‘unknown’ or ‘undiagnosed’, matters can get even more challenging when the condition becomes more elusive or develops life-threatening consequences. And all of this is exacerbated by inequities in treatment and high costs of the few existing drugs that are available.

By EU standards, a rare disease is one that affects fewer than one in 2,000 individuals. And these ‘less common’ ailments are difficult to raise monies for to research, leaving large gaps in scientific and medical literature. One such disease is the poorly understood Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism (IHH).

Characterised by the absence of puberty and infertility, IHH can be compounded by potentially severe characteristics such as congenital heart disease, osteoporosis at a young age, and early onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

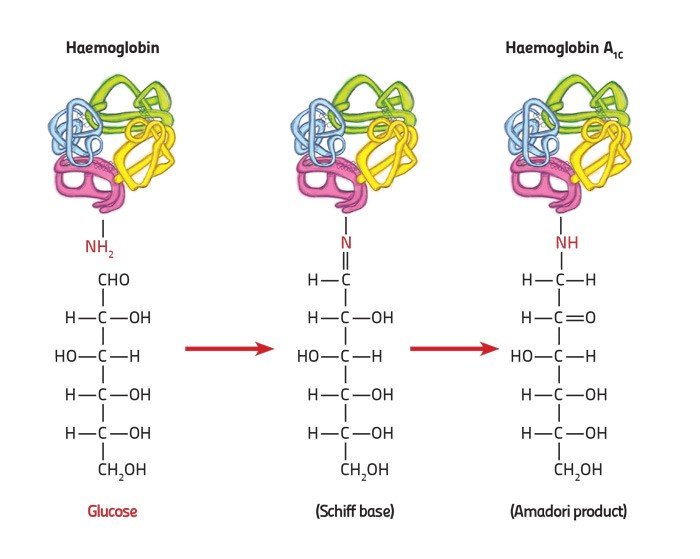

Its cause is usually a genetic anomaly, but a single genetic change can affect two people very differently. This gives rise to an unparalleled complexity that makes the cause harder to decipher. Symptoms are not clear-cut and sometimes mask the actual underlying cause, bringing about misdiagnosis and delayed treatment. Timely diagnosis is crucial for successful treatment that enables the patient to achieve puberty and induce fertility. But this is not always possible.

Under the guidance of Dr Rosienne Farrugia, I am currently analysing and expanding upon a preliminary assessment of IHH in Malta using high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technology (conducted by Adrian Pleven). With HTS, we can read a person’s entire DNA sequence and attempt to identify differences in the DNA code which lead to such diseases.

What the team has found is that some genetic variants typical of IHH are more common in the Maltese population when compared to mainland Europe and African populations. This is likely due to the reduced genetic variation of our population, shaped by successive events of population reduction and expansion throughout our history.

By mapping the genetic cause of diseases prevalent on our islands, we can help medical consultants to employ specific screening tests that are tailored for local patients suffering from IHH. Such advancements in genomic technology and personalised medicine can make a huge impact on people’s lives. And not only to those suffering from IHH; researching one disease, however rare it may be, can shed light on mechanisms that prove useful in treating many others, ensuring that when it comes to health, no one is left behind.

This research project is being carried out as part of a Ph.D. program in Applied Biomedical Sciences at the Faculty of Health Sciences.