Biex taqra l-artiklu bl-Ingliż, agħfas hawn.

Kaxxi fuq kaxxi, miksijin bl-għabra, jistennew is-sekondiera tagħmel ir-ronda tagħha. Is-sekondi jsiru minuti. Isiru sigħat. Ġranet. Xhur. Snin sħaħ. Deċennji, sewwasew.

Il-Prof. Edward Fenech wirithom mingħand il-Prof. Ġużè Aquilina, imma ġara li l-kaxxi u ta’ ġo fihom ingħataw il-ġenb għal ħafna żmien. Parti ġmielha mill-istorja lingwistika u kulturali tagħna konna bil-mod il-mod qed nitilfuha minn taħt imneħirna.

Mistura fil-kaxxi nstabu r-reel-to-reels li l-Prof. Aquilina, missier il-Lingwistika Maltija, kien uża biex jimmortala l-ilħna bil-kisra djalettali ta’ bosta kelliema minn lokalitajiet differenti f’Malta u Għawdex.

Illum, kulma jmur qed nagħrfu u napprezzaw il-ġmiel ta’ mużajk li jsawru d-djaletti tal-gżejjer Maltin. Iżda, sa ftit snin ilu, min jitkellem bid-djalett aktarx li kien jitqies ta’ klassi baxxa. Ħtija tal-preġudizzju, xi wħud ippruvaw jinfatmu minn dan l-aspett ewlieni tal-identità kulturali tagħhom. Il-preżenza tad-djalett qajl qajl bdiet tiddgħajjef. In-nies tħalltu fiż-żwieġ, u magħhom tħalltet il-lingwa. Min mar joqgħod f’raħal ieħor kien espost għal djalett differenti, u t-tfal bdew imorru l-iskola u jitgħallmu l-Malti standard, ‘il-pulit’, sajjem minn xi karatteristiċi li jżewqu t-taħdit.

Il-Prof. Aquilina minn kmieni għaraf li ħaġa daqstant sabiħa ma kellniex nerħuha tiżolqilna minn idejna (jew ħalqna f’dan il-każ), u fis-snin sittin u sebgħin, irħielha lejn xi rħula Maltin u Għawdxin, idur bir-reel-to-reel recorder, jitħaddet man-nies dwarhom infushom, dwar is-snajja’ tagħhom, u dwar it-tradizzjonijiet li wirtu bil-fomm u bl-id. Bil-mikrofonu kien qed jaqbad il-ħsejjes u l-forom tad-djaletti, imma mhux biss. Ma’ kull intervista, kien qed jiddokumenta stil ta’ għajxien li llum jinħass tant ’il bogħod. Bl-għajnuna ta’ Benedikt Isserlin mill-Università ta’ Leeds ġabar 92 audio file b’madwar 50 siegħa taħdit djalettali, mhux kollu tal-istess kwalità. Bil-materjal miġbur, Aquilina u Isserlin fl-1981 ħarġu pubblikazzjoni li tittratta elementi fonoloġiċi tad-djaletti. Daqs tletin sena wara, John Paul Grima sema’ l-audio files wieħed wieħed, u b’reqqa kbira ddokumenta u kkataloga l-ħidma fit-teżina tal-Baċellerat tiegħu.

Fost l-ilħna li ltaqa’ magħhom Aquilina, hemm tal-iskarpan mill-Għarb, li, hu u jmertel il-ġild, jispjega l-proċess tal-ħjūta bl-aktar ġild fin Ingliż. Tħaddet mal-għaġġiena mix-Xagħra, li tispjega kif ħobża titwieled mid-dqiq, tingħaġen u tinħadem sakemm issib ruħha fuq it-tilar, lesta biex tinħema. Tkellem mar-raħħala Żurriqija fuq kif iġġiżż in-nagħġa biex tħaffilha s-suf, fuq nagħġa żgħira li għad ma kellhiex ħaruf (għabura), u n-nagħġa li qatt ma kellha (ħawlija). Skopra kif ix-Xlukkajri jaħslu l-ħwejjeġ bl-ilma salmastru fil-Fawwara tal-Ħasselin, u sema’ kif tinħadem u titħejjet il-bizzilla f’Ta’ Sannat, skont il-bixra li l-lingwa tieħu f’kull post.

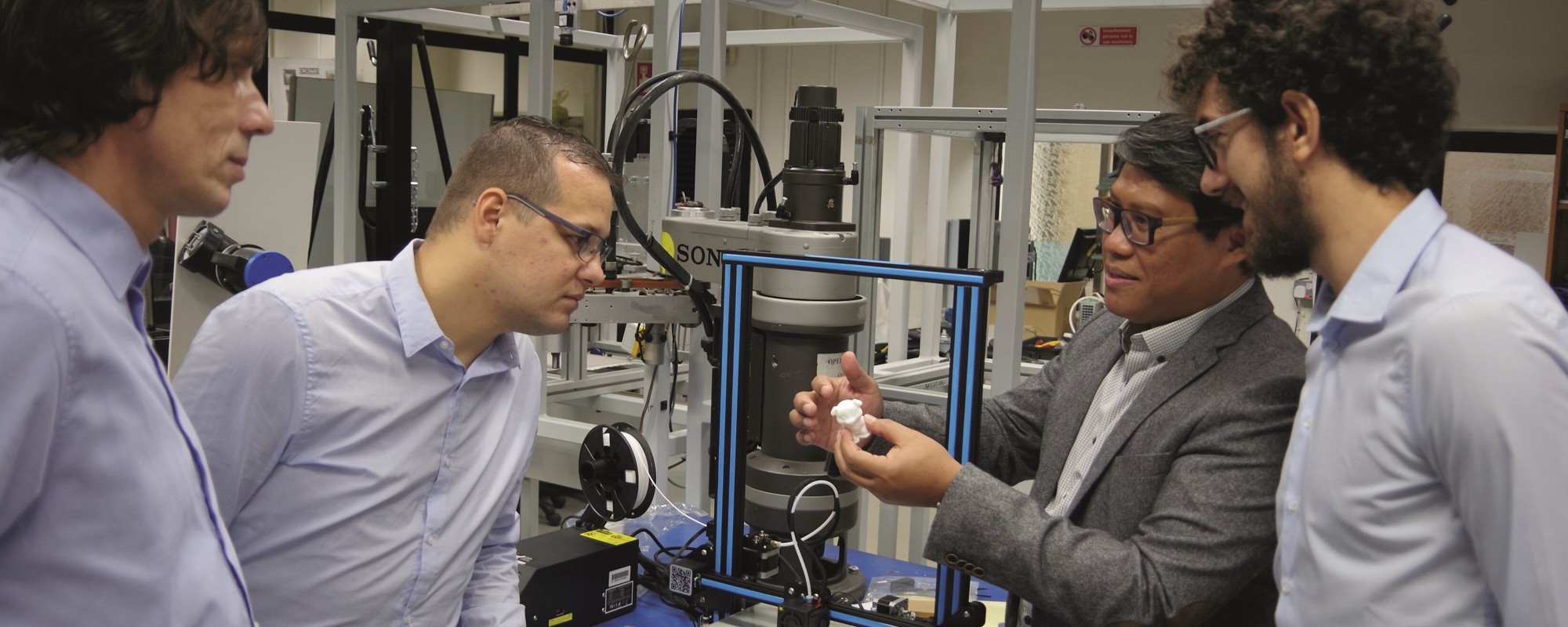

Dan il-materjal prezzjuż inżamm f’kaxxi li maż-żmien għoddhom intesew. Kien b’kumbinazzjoni li wara ħafna snin ir-reel-to-reels sabu ruħhom fl-istudio ta’ Anthony Baldacchino. U minn hemm, fuq l-inizzjattiva tal-Prof. Alexandra Vella, beda l-proċess biex il-materjal maħżun fihom jiġi ddiġitalizzat. Xejn ma kien faċli li l-kontenut tar-reel-to-reels l-antiki jinqaleb f’format diġitali. Illum, l-ilħna tal-imgħoddi f’dan il-format, ftit ftit qed jittellgħu fil-portal tar-riċerka malti.mt, li d-Dipartiment tal-Malti se jniedi fix-xhur li ġejjin, ħalli jkunu aċċessibbli għall-istudjużi u għal kull min għandu interess fid-djaletti, is-snajja’ tradizzjonali, u b’mod ġenerali l-ħajja fl-ewwel snin ta’ wara l-Indipendenza.

Bis-saħħa ta’ dan il-proġett, ikkoordinat mill-Prof. Alexandra Vella, il-Prof. Ray Fabri u Dr Michael Spagnol, dan il-felli tal-istorja tagħna jista’ jitgawda mill-pubbliku u jiġi studjat mir-riċerkaturi ħalli nifhmu aħjar il-qagħda lingwistika tant rikka fil-gżejjer żgħar tagħna. Għax dawn l-ilħna jsawru ħolqa f’katina li tixhed li, għalkemm minn fuqhom m’għaddewx aktar minn ħamsin sena, il-ħsejjes, ir-rakkonti, l-għerf u d-drawwiet li fihom inewlulna pinzellati minn ħajja li m’ilha xejn imma ilha ħafna.