Does 3D printing have what it takes to make manufacturing environmentally friendly? Using only as much material as a part

or product requires, it would seem so. Iren Bencze asks what, then, stands in the way of its widespread adoption.

From Science in the City to robotics festivals, a signature sight at technology-related events is a crowd of hypnotised-looking children, following a 3D printer building, layer by layer, a vase or animation character. From dentistry to design, the technology is promising to make future manufacturing customisable and renewable (as materials can be made from starch or roots). Yet, according to Newsweek, the industry suffers from ‘a gulf between expectations and realities’, and some analysts have claimed the hype is now over. So, can we make 3D printing live up to its promises?

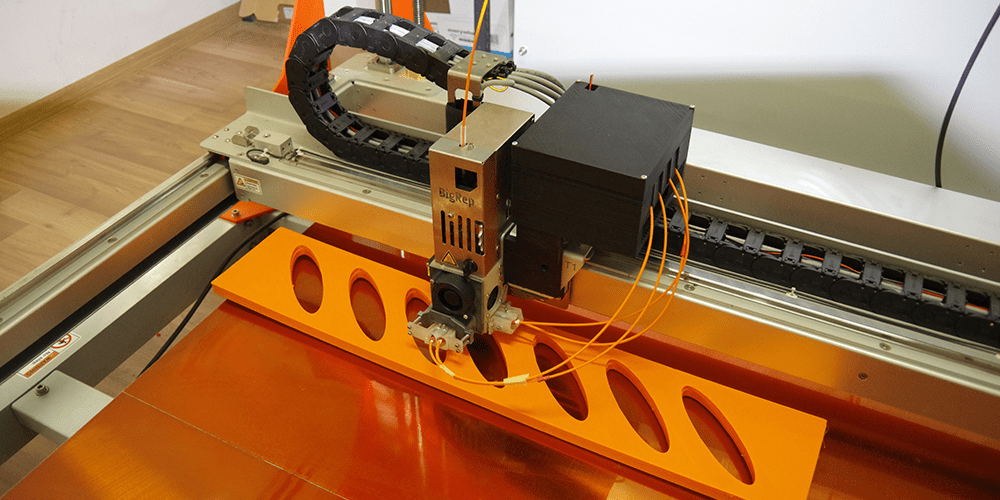

The answer may lie in controlling irregularities. In fused filament fabrication (FFF), one of the 3D printing methods, a computer controls the release and depositing of melted thermoplastic, layer-by-layer. The molten material solidifies under exposure to a cooler environment, and the printer can add another layer until the 3D object materialises. Just like ordering a prototype from the Replicator on Starship Enterprise, right?

Well, not quite. Yet. While fused filament fabrication serves research, engineering, and development, it wrestles with adhesion-related problems. Molten thermoplastic solidifies as it cools, so the deposited layers can shift, delaminate, warp, or form irregular walls. Under these circumstances, the mechanical properties of the 3D-printed object also suffer from decreased tensile strength and defects caused by porosity. In other words, they suffer from the same drawbacks as wood, which is stronger along the grain than across it.

Award-winning company Laser Engineering and Development Ltd undertook the challenge to overcome this major hurdle. Their proposed LASeeeR next generation FFF 3D printer uses innovative laser technology to try to bring about a great leap forward in the industry.

The LASeeeR technology uniquely uses laser heating to strengthen the inter-layer bond while printing objects. This should increase their strength. Project coordinator Gabor Molnar hopes that the advance will overcome the hurdles 3D printing faces in manufacturing.

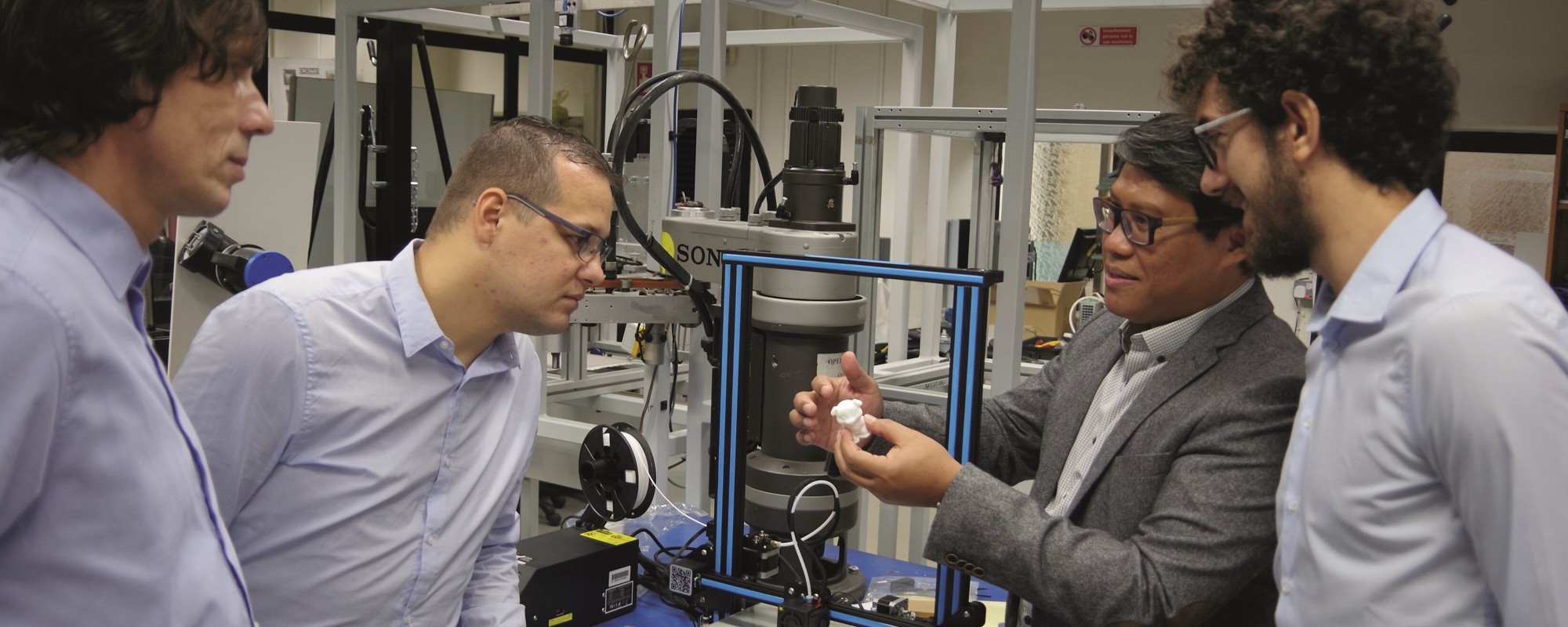

Funded by MCST’s FUSION fund, Laser Engineering and Development Ltd is developing a functional prototype that can be integrated into a regular FFF 3D printer. They are collaborating with the Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering (DIME; Faculty of Engineering, University of Malta [UM]) for their specific expertise on polymers. The micro enterprise, which has under five full-timers, had never cooperated with Malta’s academics before, but with the help from the Knowledge Transfer Office at UM, they were introduced to polymer processing and testing specialist Dr Arif Rochman. He brought to the project extensive experience with industrial partners, and DIME contributed state-of-the-art 3D printers for both metals and polymers.

Reflecting on the early days of the project, Molnar notes that their main challenge was HR-related. Malta being a small country, it was difficult to find creative professionals with the right expertise. With nationals from Hungary, Italy, Malta, and Indonesia on the team, the current challenge is multicultural management. ‘While it is difficult to coordinate various viewpoints and work styles, cross-cultural knowledge sharing should be the norm for any project with global impact,’ Molnar says.

In the LASeeeR project, DIME is developing special filaments from different polymers that can highly absorb laser radiation. Molnar hopes that the combined academic and industrial expertise will make 3D printing faster. On the average, it can take an hour to print a 5–15 cm tall object with FFF technology. The time depends on filament material and thickness, layer thickness, print nozzle temperature, and so on. Using concentrated energy and more precisely controlled heating, the proposed technology will be able to melt a thicker filament, a 50W laser can heat up the filament from room temperature to printing temperature in one tenth of a second. 3D printing should get hotter and faster.

By overcoming problems in build speed and mechanical strength, this Maltese innovation could contribute to more 3D printers being used to manufacture goods. These printers would make manufacturing more environmentally friendly by reducing the amount of material used and being able to use plant-based polymers. The team’s hope is that beyond patenting the new technology of laser heating to strengthen the inter-layer bond, they will be able to introduce it to factories worldwide.

The print version of the article incorrectly identified a team member’s nationality as Malaysian rather than Indonesian. We apologise for the mistake.

Comments are closed for this article!