Everyone eats. Eating food straight out of a packet is the norm in our fast-paced world — a simple fact that makes food science ever more important. We need safe food. THINK editor Dr Edward Duca met up with researcher Dr Vasilis Valdramidis to find out about the latest tech.

Food safety is serious business. In Germany during 2011 a single bug hospitalised over 4,000 people causing 53 deaths. Scientists learnt afterwards that a strain of E. coli had picked up the ability to produce Shiga toxins. These natural chemicals cause dysentery or bloody diarrhoea. The bacteria were living on fresh vegetables and it took German health officials over a month to figure out which farm was responsible.

On the 2 May, German health authorities announced a deadly strain of bacteria in food. By the 26 May, they pointed their finger at cucumbers coming from Spain. They were wrong. The mistake cost the EU over €300 million in farmer reimbursements. Genetic tests found that the bacterium on cucumbers was different than the one which was killing people. The researchers continued to ask people who were infected what they ate: raw tomatoes, cucumbers, and lettuce remained the prime suspects. Till they tested organic local bean sprouts from a farm in Bienenbüttel, Lower Saxony. By the 10 June, the farm was forced to shut down after it was pinpointed as the source. The sprouts were contaminated from the seeds’ source in Egypt.

‘These bean sprouts are found in several ready-to-eat foods, you could have it in your sandwich and not realise that you’re eating it,’ said food scientist Dr Vasilis Valdramidis (University of Malta). This is the reason why it took German officials so long to find the source. Having to rely on people’s memory of what they ate before becoming sick, something as inconspicuous and mild tasting as a bean sprout can be forgotten. Precisely why industrial food safety is so important: it saves lives.

Cleaning food

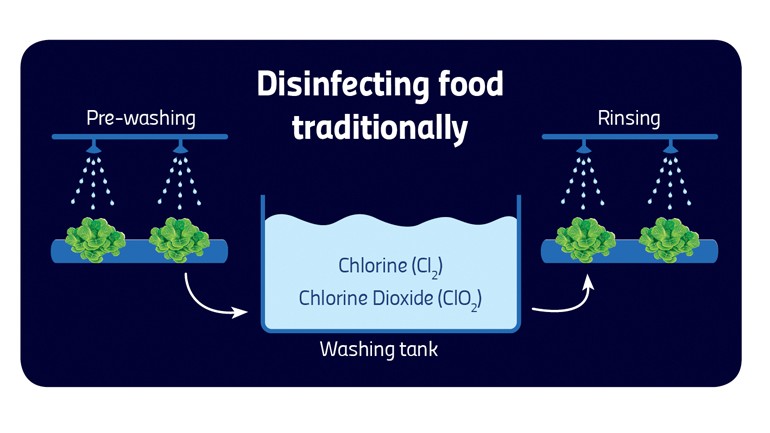

‘There is no natural sterile environment,’ stated Dr Valdramidis who studies new ways to disinfect ready-to-eat lettuce, cabbage, and bean sprouts to make our food safe. Most bacteria come from nature or during handling. ‘After harvesting, there are 3 different steps for processing fresh produce. First, they are washed to remove all external material. Second, there is the disinfection process. […] Third, they apply a decontamination treatment that most commonly is chlorinated water.’

Dissolving chlorine dioxide powder into water makes most of the industrial chlorinated water. Chlorine is found in tap water so is relatively harmless at low concentrations, but ‘the less we have of this chemical the better for our health, because there are some side effects,’ explained Dr Valdramidis. ‘It can react with the organic substances of food products and produce some compounds […] that aren’t healthy.’

The environment is another problem. Chlorinated water ends up in ground water or other water sources. Elevated levels of chlorine can decontaminate vegetables but also natural habitats.

Dr Valdramidis’ group works to reduce the amount of chemicals, water, and energy used. Fresh water is a precious resource with less than 3% of the world’s water being fresh. In Malta, pressures on fresh water use are intense and the country is facing a little known water crisis. Worldwide energy efficiency is a hot issue, with both environmentalists and industry pushing for greater efficiency and cheaper energy bills.

From Oregano to Music

The herb oregano can be concentrated with its essential oils extracted. Surprisingly, at the right concentration oregano slows bug growth. Dr Valdramidis’ group is taking advantage of this antimicrobial effect to disinfect vegetables. ‘And it tastes better, but it depends on the amount; if you use too much it is bitter.’

The food industry’s bottom line is cost. ‘The extraction process is quite expensive but now the price is going down. [The food industry already] use oregano oil as antimicrobial agents in feeding products for animals. Their aim is to reduce the use of antibiotics. It [oregano] is becoming more and more accessible.’

Oregano oil might be more expensive, but it is a natural product that is non-toxic. Another advantage is that, ‘if the plant cells are relaxed then these essential oils can penetrate’ into the plant disinfecting it thoroughly. Once optimised, it could easily replace chlorine water, reducing the amount of damaging chemicals used.

Oregano could replace chlorine water, but what about the amount of water? Another technique, which uses sound to clean food, could help. Think about ultrasounds used to scan pregnant women. Those ‘operate on megahertz and create images, this [technology] operates on kilohertz and is powerful enough to create physical changes at a microscale’, which means they are high power systems. It works by pulsing sound waves at your submerged vegetable or fruit of choice. The sound creates bubbles that implode, creating a very high pressure and temperature. This energy can kill the bacteria. When Dr Valdramidis gets it right, it cleans the vegetable.

The process is even more extraordinary. The sound wave causes ‘a molecule of water to split and create [the molecules] hydrogen peroxide and other radicals, which are very unstable’ so they react with everything around them (including bacterial DNA), either becoming water again or attacking cells. ‘They affect the membrane of the bacterial cell,’ said Dr Valdramidis, ‘killing it.’ They can also damage plant cells, so the technique needs fine-tuning to get it right. By measuring the appearance, amount of vitamins, enzymes, and other nutrients lost by the procedure, researchers can tweak it to maximise its antimicrobial value and minimise its damage to the vegetable. To continue improving the technique a lot of his work is spent trying to understand exactly how the procedure works and why the bacteria die.

The ultrasound still needs water to work. Water cannot be removed from the equation because bubbles can only form in water and sound also travels better. Water quantity can be reduced. When using chlorinated water, another step is needed to rinse off the chlorine. In this case, it can be skipped. There is an even more radical technique that might bypass water altogether.

A lightning storm

Plasma is made up of ionised air. In nature, plasma is made by lightning, leaving a tell tale ozone smell. Food scientists can pass high frequency electricity through air to create a bacteria-killing plasma stream.

Ionised air kills bacteria because it forms radicals and ozone. Electric discharges create radicals and turn oxygen into highly reactive oxygen radicals (an unstable oxygen atom) or ozone (3 oxygen atoms joined together). These products can react with bacteria and inactivate them. Like sound waves they can also affect food. ‘High levels of ozone can bleach food by oxidising the product. There is no ideal technology,’ stated Dr Valdramidis. The difficulty in all of this is how to kill the bacteria and not the plant. Everyone wants salads with a nice colour, good flavour, and high nutritional value.

On the other hand, the beauty of this technique is that you can zap the food in its packet. So imagine just rinsing the food with a little water, wrapping it up, and finishing off the cleaning process with an electric pulse. The package can be delivered to your local grocer with minimal use of water and your mind at rest. Both sound waves and plasma could also spell the end of excessive chemical treatments.

A computer model of a fruit

Measuring microbe levels is the only certain way to know if food is safe. Traditional methods are labour intensive, time consuming, and expensive. Scientists first need to remove the bacteria from the product, then dilute the bacteria, then count the cells directly with plate counting techniques or under a microscope. More modern techniques use molecular methods such as PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) to find out the specific type of bacteria. This can make a huge difference since not all bugs are created equal.

To reduce costs and speed up the process, Dr Valdramidis uses mathematical models to predict the shelf life of products and apply the right decontamination process. ‘We want to predict the amount of bacteria present, so with these equations we are trying to describe how fast the bacteria are inactivated then [how fast those that survive] grow,’ explained Dr Valdramidis. The number of bacteria predicts food safety and how fast it rots.

For mathematical modelling to work, first ‘data needs to be collected […] by performing some experiments. Then I try to describe how the population responds and behaves using these equations. If I can verify this model, then I can come to you and tell you, ‘look, this product has these specific characteristics, within the range of this model, I can tell you that it will expire in 15 days and you don’t need to do any experiments.’ It’s a very powerful tool but it has to be well validated.’ It saves a ton of money, but you must be sure of the model otherwise people could be harmed.

Current maths has its limits. Scientists are still trying to correctly model a single cell. Plant or bacterial cells are complicated machines, with proteins, DNA, and other molecules all jam-packed together working synchronously for a cell’s survival and reproduction. To make things easier, scientists simplify cells when simulating them then consider a whole group of them, a population. Researchers test the whole population. If Dr Valdramidis’ group attempts to model a single bacterial cell’s growth in Malta, he would have to use the University’s supercomputer called ALBERT. Maths on this level uses a lot of computational power.

Taking the cell modelling idea to its extreme, some food scientists are trying to model every plant cell to make a complete fruit — a virtual fruit. They model, ‘the exchange of gases and so on since fruit is still respiring, still alive after harvesting.’ To control the respiration process, they ‘try to control the amount of [the hormone] ethylene, oxygen gas, and so on.’ They also use these models to simulate modified atmospheres around food seeing how they influence respiration rates. Shelf life is affected by plastic packages with different holes sizes, types of plastic, and other parameters. All of these properties are pumped into the mathematical equations and tweaked to maximise shelf life. ‘If you slow rates down, the food lasts longer and can be stored for a longer period,’ explained Dr Valdramidis, which makes both companies and consumers happy.

Working with industry

Dr Valdramidis is young but has a long career in fundamental research. He has modelled and tested the rate of bacterial growth (and inactivation) at changing temperatures, and even investigated how to decontaminate biofilms in industrial food processing plants. Importantly, he has looked into quantifying and speeding up the analysis of microbial levels on food to give an actual ‘best before’ date. His approach always coupled experiments to test his maths and predictions.

Innovations in food science aim to bring down prices, use less water, fewer chemicals, and less energy. For these reasons, Dr Valdramidis is now at a stage where he can collaborate with industrial partners. In Malta, he has already met with the Chamber of Commerce through the creation of a Food Industrial Advisory Platform. With this platform ‘we plan to organise workshops every 6 months. Once to speak about our activities and another to speak about subjects that are of interest to SMEs [Small to Medium Enterprise, or industry].’ Malta is run by food SMEs; they account for 65% of GDP.

Researchers need to work with industry — a statement on everyone’s bucket list. Its importance cannot be understated, since it is unlikely that universities will receive substantially more research funds unless businesses start seeing these institutions as partners. And, they could save or make big bucks by investing in research. Dr Valdramidis’ work is a clear call for collaboration.

Working with others is what drew Dr Valdramidis to Malta. ‘I firmly believe in collaboration. A lot of my [research] publications are not just from the university I would be working in but others as well.’ By opening arms wide open perhaps we can prevent mistakes, like those of the German health authorities, invest in research that reduces waste, and cleans our food just by playing a song at the right energy.

[ct_divider]

Some of the above research is supported by a Marie Curie FP7-Reintegration-Grant within the 7th European Community Framework Programme under the project ‘Development of novel Disinfection Technologies for Fresh Produce (DiTec)’, and part-funded by the Malta Government Scholarship Scheme.