Students tutoring students

According to MATSEC, two in every three 18-year-old students don’t make it from sixth form to university. Gail Sant speaks to the team behind LearnD to find out more about their take on student-centred education.

You love films, videos, and photos. You relax while watching Netflix, and learn new skills on platforms like Skillshare and YouTube. Me? I adore the written word. Books, magazines, blogs are all I need to live a happy life. People are unique. And we all learn things in a unique way.

Different people require different teaching methods to learn. But most classroom set-ups involve one teacher, one lesson, and thirty-odd students. The lesson is interpreted in thirty different ways; a few absorb more than others, leaving some in need of extra help to ace their maths test. And how do they do that? With private lessons.

In Malta, private lessons are the go-to solution for students struggling with a subject. However, these sessions tend to be a carbon copy of school classes: one tutor, one lesson, multiple students. This problem was the seed that gave rise to the education-focused startup LearnD.

The philosophy

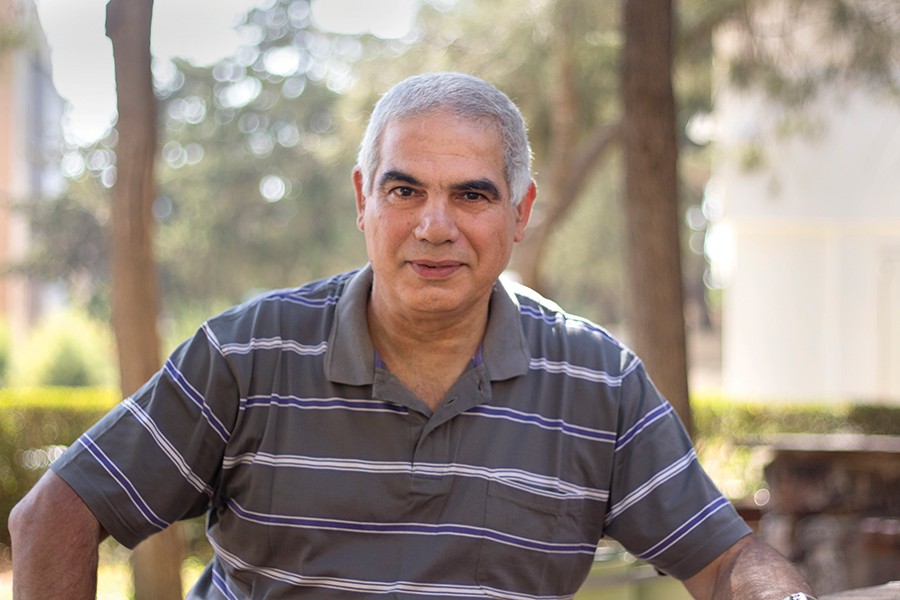

LearnD is a tutoring app invented by Luke Collins, Jake Xuereb, and Dr Jean-Paul Ebejer (Centre for Molecular Medicine and Biobanking, University of Malta). The concept behind it is simple, Ebejer says; ‘it’s a bridge between students who can act as mentors and students who need the help.’

LearnD does away with the one-size-fits-all standard of teaching and offers students tailor-made tutoring. Individuals are treated as such, their problems tackled through dedicated sessions. As a student, you don’t need to sit through a whole syll

abus of private lessons. The idea is to identify your weak points and hone in on them in select sessions. This is both time and money-efficient.

Xuereb believes ‘private lessons can make students lazy.’ They don’t need to evaluate their problems, or focus on where their issues lie. Not when they know they’ll just cover all the topics at various points during their weekly appointment with their second teacher on Tuesday night. LearnD focuses on dividing attention unequally. If you get an easy A in physical chemistry but struggle to pass organic chemistry, it only makes sense to give the latter some extra TLC. To get to this point, students need to take a step back from their desks and separate their strengths from their weaknesses.

This is also a big plus for tutors who don’t want to (or can’t) commit to teaching a whole syllabus. They can simply prepare a lesson for the requested topic and leave it at that, earning some extra money to accompany their stipend while gaining teaching experience.

But LearnD isn’t just about academia. Some lecturers lose touch with ‘the student life’, distancing their relationship with students. Conversely, student-tutors know the struggles a peer would be going through and can provide support. ‘No one would have a better understanding of what a sixth former needs to do to get into medicine than a medicine student,’ says Xuereb. ‘Through LearnD you can find people who have been through the exact same thing and who can offer their best advice on anything from time management to de-stressing, and everything else.’

Making it happen

The original concept was more related to finding a way for academically inclined 6th form students to contribute productively to society,’ says Xuereb. When he spoke to Collins, a fellow University of Malta student and Xuereb’s former maths tutor, the idea went from ‘an online local network’ to ‘app’. At the time, there were no local tutoring apps.

Despite both being passionate about the idea, they soon realised that they needed someone with business experience, and that’s where Ebejer came in: the LearnD team was born!

The process that made this idea into reality was not a simple one. Xuereb and Collins spent over six months working on the app, learning about the tech behind app-making and coming up with a business plan.

They got their break when they won the Take-Off Seed Fund Award in 2018 and got the necessary funds to make the app a reality. They quickly got the ball rolling, hiring designers, app developers, and marketing agents. The team grew; the app was built. Then, during the KSU Freshers’ Week in 2018, the app was partially launched, inviting potential tutors to apply. The app is now fully launched and available for students.

Troubles

As with all big projects, the team ran into a few setbacks along the way. One prominent techy mishap didn’t allow them to launch the app on the Apple Store, making it difficult to keep up with the launch date.

Since the app is used by underage students, there were also a lot of safety features which needed inclusion. Tutors upload their police conducts and ID cards. Also, to make sure LearnD’s service is reliable, the team not only analyses tutors’ qualifications, but they also try and test each applicant out themselves. And for accounts which belong to students under the age of 16, parents need to authorise any communication which goes on through the app.

The team persisted through the struggles they encountered and continue to work hard to solve any problems which crop up. Despite difficulties with time management, Collins and Xuereb, both undergraduate students, expressed how this app allowed them to dive into the working world. They gained entrepreneurial maturity, understanding the importance of a reliable team which shares the same ideas and work ethic, as well as dividing funds for the project’s overall benefit.

A LearnD future

The LearnD story doesn’t stop here. ‘We want to renovate the education space,’ says Ebejer, adding that they wish to take the next step and make it internationally available. Malta’s size makes it the perfect test bed, but they think that the app shouldn’t be limited to its home.

According to MATSEC, in 2017 only 27% of 18-year-old students acquired the necessary qualifications to get into university. Collins expressed that students ‘shouldn’t get lost’ because of a bad exam result or because of a mismatched student-teacher scenario. Students deserve to be treated as individuals, and LearnD can offer them that.