A life studying life

Prof. Patrick J. Schembri lives for biology. His long career has brought him in touch with an endless list of creatures that includes fish, beautiful white coral, sharks, limpets, crabs, and ancient snails. Edward Duca met up with Schembri to find out more about the life around Malta.

I was nervous. I still remembered fumbling for excuses for handing in my assignment a few days late. Prof. Patrick J. Schembri’s stern gaze does not take excuses. This time I entered his office to learn about the wealth of research under this man’s belt. With over 150 refereed papers to his name I knew I would not leave disappointed.

In 1982 Schembri returned to Malta after a doctorate at the University of Glasgow and a post-doctorate in New Zealand.

‘In Scotland, I was working on animals that came from a depth of 40m and in New Zealand with animals that came from the whole span of the continental shelf and upper continental slope at depths down to about 900m. For that you need a research vessel, crew, collecting equipment, and so on. I came to Malta and there was nothing’, said Schembri. This did not stop him, like the animals he studies, he just adapted.

‘Nobody has looked at the ecology of shores in Malta before, so I decided to do that.’ And as simple as that, Schembri went from studying deep water animals to the near shore. The techniques and equipment needed are completely different — a diverse research background that must have helped him in his long career. After many years, Schembri returned to studying life in deep waters, invasive species, and many other things, but more on that later.

Back in the 80s the Internet simply did not exist locally so Schembri’s biggest problem was not equipment but sourcing academic journals. Every scientist needs to constantly read journals to keep up to date with the latest findings. It is essential for research inspiration, to see knowledge gaps that can be studied, to learn new techniques and knowledge, and to avoid repeating others’ research. Schembri, ever determined, went to great lengths to get the information he needed in order to research and publish.

‘Thanks to my mentors I was brought up with a culture of publishing.’ The renown of every scientist depends on the importance of the journals they publish in and how much they publish. Neither was a problem for Schembri. ‘I produced my first paper before I did my A levels. In the early 1970s, I improvised some apparatus to do experiments on something that you would [normally] need sophisticated equipment for, so rather than using a nitrogen chamber, I used a plastic bag to which I attached kitchen gloves, and it worked.’ After some encouragement from his tutor the paper was written as a note that was published in School Science Review. He also published around six papers from his Master’s degree. No small feat, I have not achieved this even after a Master’s degree and a Doctorate.

A Master of all Trades

The breath of his studies is stunning. With his students, Schembri has studied animals which have invaded Maltese waters. These include the nimble spray crab (Percnon gibbesi) and the non-indigenous Red Sea mussel (Brachidontes pharaonis), which, unlike all native mussels is forming mussel beds with thousands of individuals. He has studied the seabed’s ecosystems that happen to be vital to maintain fish stocks. He has even delved into Malta’s ecological past analysing samples from cores drilled in Malta’s coastal sediments studying sub-fossil molluscs to piece together the Island’s early history. These were only possible through collaboration with many scientists and a vast army of students.

Percnon gibbesi

Photo by divemecressi, flickr

His collaborations have been essential. Schembri was contacted by Italian researcher Dr Marco Taviani to survey Malta’s deep seas. Taviani has access to the multi-million research vessel Urania. The 61.3m ship has on-board laboratories for geological, chemical, radiological, geophysical, and biological research. To make it in Malta, ‘if you don’t have enough resources you have to improvise and collaborate, especially with overseas researchers who do have the resources. And it worked’.

Schembri has gone further than just making it work. He has flourished. His strategy involves participating in EU funded projects (to bring in the money) while keeping very ambitious long-term projects running in the background on a shoestring. The only problem is that for ‘all the EU projects, the agenda is set internationally. While [for local projects] the funds are minimal, I get a few hundreds a year. But I am free to study what is interesting and important for Malta.’

Managing Fish

BENESPEFISH is one of his locally funded projects. ‘I want to find out what kind of habitats we (Malta) have and how fish interact with them.’ By studying what fish eat and where that food grows, by seeing the nursery grounds and spawning areas of the fish, by researching how the impact of fishing techniques affects the sea floor that ends up damaging the ecosystem. For example, in collaboration with the Government’s Fisheries Agency, students under Schembri’s supervision studied the effect of a type of fishing technique called otter trawling. They discovered that it can adversely change the benthic (seabed) ecosystem and that the trawling should be done in corridors, with spaces between them to allow the recuperation of the seabed, and therefore the dependent fish stocks. This will help fish stocks recuperate and fishermen to retain their livelihood.

“For some strange reason, beforehand fish were one thing and the rest of the sea was something else”

The above is called the ecosystem approach to fisheries management. Back in the early 2000s ‘Matthew Camilleri from the Fisheries and Aquacultures Department got involved in a FAO (Food and Agriculture Organisation) project called MEDSUDMED,’ that was pushing for this approach. ‘So he asked if I could help out with the ecological aspect. […] Ecologists entered the picture because in this approach fish started being looked at as part of the ecosystem. For some strange reason, previously fish were one thing and the rest of the sea was something else’ — a clear reason for fisheries scientists and marine biologists to work together to be able to give the right scientific advice to the Government.

The BENESPEFISH project hinges on a healthy relationship with the Government. The Government Fisheries Agency commissions the MEDITS trawl survey to monitor the health of fish stocks, which are mandatory for all EU member states that border the Mediterranean. These surveys need to ‘follow a strict protocol’, perfect for science. However, the survey ‘is limited to about 40 species. They still get everything else such as benthic organisms [that live on the sea bed] that they used to just throw overboard. So I said to them, okay why don’t you keep it, give it to me, I work on it, then I give you the results. […] If I had to hire a fishing trawler and go out myself for 14 days it would cost me around €190,000, crews and everything. Instead, by collaborating, we get this data at a low cost. All I need to pay for is for insurance, fixatives, sample containers, and a research assistant to collect the samples. So that’s what the University funds, it funds the research assistant and materials. […] So you [the Government] get information which you would not normally get because you are not a research institution.’ Clever and it worked.

These discards are valuable to find out about the ecology of the fish in our seas. ‘They were going to get rid of a few hundred sharks (the small-spotted catshark, Scyliorhinus canicula) […], so I got them and one of my students analysed their stomach contents which told us a great deal about what the fish feed on and also where they feed. […] They feed on fish but also on the benthos, the bottom material.’ From 532 stomachs sampled, over half were eating teleosts (a group of bony fishes) and nearly one fifth were eating crustaceans, with even some cannibalism. Male and female catsharks had different diets. To keep catshark populations healthy these food sources need to be maintained. The seabed is vital.

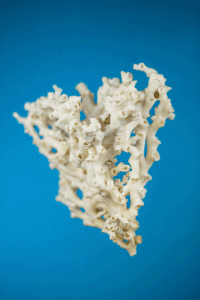

These MEDITS surveys have led to some surprising discoveries. During a survey one of Schembri’s students picked up a piece of white coral which she brought back to be identified in the lab. It turned out to be the deep water coral Lophelia pertusa that builds reefs. Schembri still had this piece and showed it to me. As I picked up this brilliant white coral he told me, ‘this is just a piece of a much larger structure. You can see the remains of some the individual animals [it is a colonial species made of many individuals], the cup-like structures with grooves.’ It is such a different species — out of this world. Schembri and his group reported finding this coral around Malta that attracted Marco Taviani (Institute of Marine Sciences, National Research Council of Italy), who was a colleague of Schembri, to organise a research cruise. Using the Italian research vessel the Urania they explored Maltese deep waters. This was the first of three such cruises that Schembri’s research group were invited to participate in. During one of these cruises they found other species of corals including the endangered red coral (Corallium rubrum), exploited since antiquity to make jewellery. They saw it at depths never seen before, around 600–800m, which is two to three times deeper than previously. When studied, this deep water population was found to be genetically isolated from others, probably because the different populations were not breeding amongst each other.

Malta’s Coast

When Schembri first came back to Malta he started working on its shores. But our coasts are not just beaches and cliffs. ‘Inland the coastal area extends as far as sea spray carries, since this renders the soil saline and therefore only adapted plants can thrive. […] Offshore, the coastal area extends to depths of 150–200m as material from the land, like sediment, still finds its way to the seabed even at those depths.’ That is a huge area for a researcher to cover, but Schembri wants to record all its habitats, obviously with a lot of help.

Enter the project Faunistics and Ecology of the Maltese Islands (FEMI), ‘the aim is to have an inventory of what we’ve got. […] I want to understand what habitats we have and which species live there.’ To cope with such a massive project, Schembri splits it up into bite-size research questions that his students can tackle over a few months (or longer if it is a Master’s or a Doctorate project). ‘The results of each small project contribute to the whole. […] By now I would say that over the years the number of people who have contributed to the project must be at least a hundred, although it is usually around six at any one time.’ Many of these student projects lead to research publications coming out from the University of Malta’s Department of Biology.

One of the most important things for the FEMI project is to figure out the state of our current environment. By knowing how things are we can tell how they are altered by future change. Back in 1998 Schembri, Dr Mark Dimech and Dr Joseph A. Borg studied how fish farms in St Paul’s Bay were affecting the ecosystem underneath. The nutrients and waste were reducing the biodiversity immediately under the cages to around a range of 30m. In between 50–170m, the fish farm unexpectedly increased the number and diversity of invertebrates. Without knowing the species normally growing in sea grass meadows this would be impossible.

By studying Malta’s coast and offshore waters for so long, Schembri can say which areas and habitats around Malta have the greatest diversity in species and which are at risk. These tend to overlap; on land the sand dunes and saline marshlands need to be preserved, while at sea it is the seagrass beds, maerl and other rhodolith bottoms, and any form of natural reef that need conservation. Such long term studies are essential to know how humans are impacting the environment and to better manage Malta’s living resources.

A Warming Mediterranean

The world is changing. The actions of human beings are warming the planet much faster than just natural processes. ‘The Mediterranean Sea is warming up. The sea is also receiving less rainfall and less terrestrial runoff, which is making the sea more saline [salty]. All of these phenomena are leading to many changes occurring at the same time. The first thing that you are getting is that native species, which were limited to the warmer parts of the Mediterranean, can extend their range to the colder parts, so southern species are moving northwards. It means that the cold-loving species cannot move further north, because we are completely surrounded by land. So populations of cold water species are becoming rarer and less distributed and if things go on like that some might become extinct because they cannot escape. In the Atlantic they just move further north, but not here, they cannot do that.’

“A warming sea is one main reason why new alien and sometimes invasive species are being found in Malta all of the time”

Loss of species is not the only thing a warming sea causes. ‘The second thing observed is that species from the East Mediterranean, which is the warmest and most saline part of the Mediterranean [and includes many species that invaded from the Red Sea via the Suez Canal], are moving westwards. Species which are warm water Atlantic species enter the Mediterranean and are now moving eastwards.’ This means that these species are all passing by Malta as they disperse, making the island an ideal monitoring station to observe a changing Mediterranean.

A warming sea is one main reason why new alien and sometimes invasive species are being found in Malta all of the time. These species are making great leaps. Dr Julian Evans, Dr Joseph Borg, and Schembri have recently (2013) found for the first time the Red Sea sea squirt Herdmania momus in Malta. This record is 1,300km further west than ever before. This sea squirt came through the Suez canal, established itself in the Levantine Sea off Lebanon, and was last observed around Greece and Turkey. It is not the only foreigner that has established itself in our waters.

Schembri and one of his collaborators Dr Marija Sciberras saw the nimble spray crab (Percnon gibbesi) all along Maltese shores. This crab is an Atlantic species that entered the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar in the late 1990s. When they found it in Malta they did not just collect it — they studied it. They found that this shallow water species grows ‘up to a depth of 3m, in other parts of the Mediterranean they have found it down to depths of 10m. It needs a habitat of cobbles or stones, it does not live on bare rock. [In Malta this means] that you find it more towards the north rather than the south, because the coast slopes down to the north and you’ve got many more opportunities for this sort of habitat while the south is mainly cliffs.’ The local shore crab (Pachygrapsus marmoratus) also beats this invader. They saw that the local crabs are much more aggressive than the invader. The nimble spray crab has mostly occupied a niche different from that of local shore crabs.

When we hear the word invader we do not imagine a mostly plant-eating crab sneaking into a new niche while the local omnivorous crab remains reigning supreme; but an invasive species ‘simply means that it spreads very quickly. [To understand] what the effect on the ecosystem is requires many years of study. We have many invaders. Another one, which is even more invasive, is a seaweed — an algae (Caulerpa racemosa) — this is now found everywhere. What does it do? What effect does it have on the local ecosystem? I don’t know, nobody does.’ This is why we need to invest more into scientific research over many years. You cannot figure out how a species is acting

overnight.

Schembri has been studying Malta’s ecology for decades. This long-term knowledge is vital to see slow trends like a warming Mediterranean, climate change, or habitat loss. When I asked him about the changes affecting Malta and Gozo, he replied in a sombre voice ‘I’ve seen a lot of change. In terms of change of habitat, apart from places which have been developed, not much has changed on the open coast. What has changed are the characteristics of the community. For example, previously you used to find large limpets, now you’ll find small limpets. That sort of thing. You haven’t lost a limpet or had a complete change in the ecosystem, but there have been changes nonetheless.’

In some places, especially sheltered areas, things have changed drastically. For his Master’s degree, Schembri collected specimen from Marsaxlokk Bay. This was many years before the development of the Freeport and Delimara power station. When he had a look at it after these developments the species he studied had vanished. ‘The bay has changed and when they started dredging it was even worse because a lot of the sea grasses disappeared. That bay was full of sea grasses before.’ Schembri does not think they will return anytime soon. Loss of sea grasses are even eroding the shore. ‘The sea grass was acting as a buffer to the waves, although it could also be because people have been building breakwaters and things which would change the current patterns which would also cause erosion. These things are complicated and without studying them it is difficult to know and nobody has looked’ — another reason for more researchers and funds being needed.

Marsaxlokk is not the only place. Especially since the 1990s the Maltese coast has been heavily built up, with developments sprouting in many picturesque areas like Armier. Dealing with this development has become a political issue, rather than seeing the consequences from a scientific lens.

Schembri’s view on this change is a bit peculiar to me. When I referred to the changes in Marsaxlokk Bay as ecological devastation he replied saying, ‘I don’t talk about ecological devastation, because what life does is that if the environment changes certain things disappear and other things take their place. Saying it is devastation is a human emotion. Scientifically it’s not what happens.’ Schembri was speaking impersonally from an ecological perspective. I find it hard to see the complete loss of a species or beautiful area because of human progress in this way. If humans are doing the destruction, humans can stop it or reduce the problem.

Ecologists for Tomorrow

Ecologists like Schembri are vital to know the changes taking place around our islands. Without monitoring our land and seas we cannot know how to preserve them so everyone can enjoy them. Nature should be for everyone to enjoy and experience.

Malta’s situation has definitely improved. ‘We have a huge marine protected area going all the way from Qala in Gozo to Portomaso in St Julians to protect all the seagrass meadows there. How are we managing it? We’re not. It’s a line on a map, but it is a first step’ since if anyone wants to develop the area the development’s impact on the ecology needs to be rigorously studied. Unfortunately, no one knows if the sea grasses are doing well or not. The problem is that the area is huge. ‘You don’t try to keep track of every single square metre of sea grass but at least you keep track of some of them. You establish a monitoring programme, the Government is obliged to do it having declared a marine protected area in terms of the Habitats Directive, and some monitoring is being done but there is no management plan.’ The problem is that Malta is an island with limited resources and 10 people abroad would perform one person’s job here. Government needs to give the environment and science more importance.

Schembri’s flexible approach to research is powerful. He makes it work despite the odds, but I do wonder how much more we would know about Malta’s natural wealth if there were many more researchers studying the Maltese environment and if they had better support. There are other researchers apart from Schembri, but they are few. For such a serious man, serious investment in research would surely make him, and future generations, smile.

Find out more:

-

Sciberras, M. & Schembri, P.J. (2008) Biology and interspecific interactions of the alien crab Percnon gibbesi (H. Milne-Edwards, 1853) in the Maltese Islands. Marine Biology Research 4: 321-332.

-

Costantini, F., Taviani, M., Remia, A., Pintus, E., Schembri, P.J. & Abbiati, M. (2010) Deep-water Corallium rubrum (L., 1758) from the Mediterranean Sea: preliminary genetic characterisation. Marine Ecology 31: 261-269.

-

Gravino, F., Dimech, M. & Schembri, P.J. (2010) Feeding habits of the small-spotted catshark Scyliorhinus canicula (l., 1758) in the Central Mediterranean. Rapport du Congrès de la Commission Internationale pour l’Exploration Scientifique de la Mer Méditerranée 39: 538.

-

Evans, J., Borg, J.A. & Schembri P.J. (2013) First record of Herdmania momus (Ascidiacea: Pyuridae) from the central Mediterranean Sea. Marine Biodiversity Records 6: e134; 4pp. [Online. DOI: 10.1017/S1755267213001127]

The School of Games

In ancient times games played an integral role in society. Whilst in today’s hyperlinked world, games have evolved into complex, sophisticated mechanisms that enthral millions. Now, however, games are dismissed as trivial, and of no real value. But is this really the case? Cassi Camilleri meets the research team gamED from the University of Malta to find out.

FundMalta

Prof. Gordon Calleja

Picture a Maltese crowdfunding website dedicated specifically to locally based creatives. It would be supported and promoted by government entities to the Maltese public, based locally and abroad. For this to work the public sector plays a crucial role in promoting the site and educating the public on how crowdfunding works.

The site creates a platform for followers of local creatives to contribute towards performances and products made by artists they love. Unlike sites like Kickstarter, products that can be digitally distributed or ordered will remain on the site doubling as a digital distribution platform for locally made works.

This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Why so Serious?

How do you help school children handle fights, bullying, and other conflict properly? You build a game, of course, and you let children take on different roles in a village. But how does that lead to resolving conflicts? Ashley Davis met researchers Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis to find out more

Do you chuckle at the thought of a serious game? The phrase is an oxymoron. How can a game be serious? Games are meant to be fun, frivolous, a way to pass the time. Or else you sometimes hear that games are anything but frivolous. That video game violence in particular is a threat to social order. The idea that games can be used to advance human understanding about the world, and that they can help us to teach, train, or motivate people in some way, is something that still needs to enter our mentality.

Designing games to explore research questions and to solve real world problems is actually a very important aspect of games research, an area of applied research that now has a strong presence at the University of Malta with the establishment of the Institute of Digital Games. Researchers from the Institute work on European-funded projects to create games that tackle serious problems affecting children and adults alike.

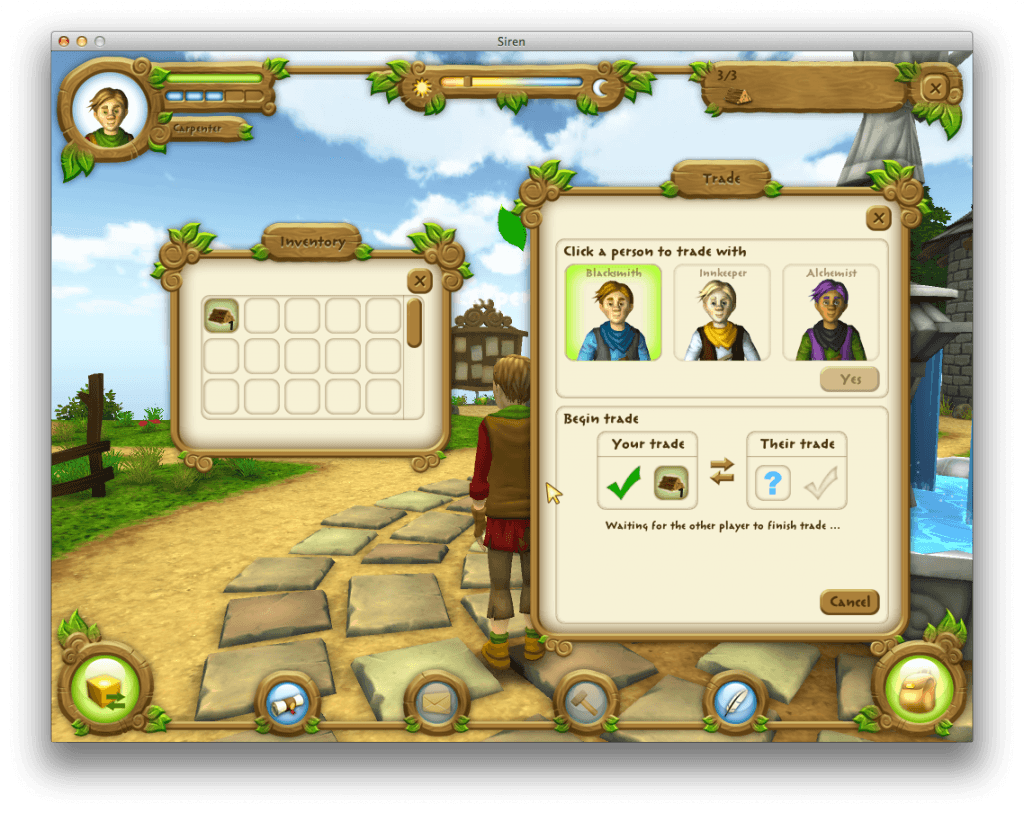

Village Voices has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards

Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis are two researchers now based at the Institute of Digital Games who work on serious game projects. Khaled’s work focuses on serious game design, while Yannakakis is a specialist in artificial intelligence and computational creativity. Computational creativity tries to build upon the latest technological innovations in human–computer interaction that enable computers to act intelligently to some aspects of human beings. These two areas, game design and game technology, represent a large part of the teaching and research strengths of the Institute.

One game that Khaled and Yannakakis recently helped develop is Village Voices which has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards. It was developed as part of the SIREN project, an FP7-funded interdisciplinary consortium made up of researchers from Malta, Greece, Denmark, Portugal, the UK and the US, along with Serious Games Interactive, a Danish Games Studio.

Let’s take a look at what makes a serious game and think about what made the project a success and what didn’t work so well.

The serious side of Village Voices aims to help school children learn conflict resolution skills. Players take on the role of one of four interdependent villages that are situated in a farm setting and given various quests to complete. Sitting side-by-side at separate computers, they may collaborate, share resources and help each other, or they may spread rumours and steal from each other. Much like any playground setting, children can play nicely, or they can be bullies.

The purpose of the SIREN project was to apply the latest advancements in game technology to the creation of serious games. The brief focused on innovations in procedural content generation, an area of artificial intelligence that automatically builds game elements like game levels or quest structures that would otherwise need to be designed manually. Another part of this innovative technology is detecting the emotions of players. Physiological responses can be measure through various tech like Electroencephalographic (EEG) sensors that can be used to detect a person’s emotional state directly by reading their brain’s electrical signals. Virtual agents were another technology that interested the research team. These agents are believable non-player characters that interact with the player with perceived intelligence.

The idea was to then create a game that would adapt to player behaviour, using emotion recognition tools to create an individual experience for each player. The decision to focus the game on teaching children about conflict resolution came later. Rather than to create a game about bullying behaviour, which is what a lot of people think of when they picture conflict between children, the research team wanted to explore the kinds of everyday conflicts that take place in school-yards. Friendship disputes, differences in opinion, and arguments over the possession of classroom items might seem trivial to adults, but they are important problems for children for whom school is their entire world. The SIREN consortium envisioned a game where players could experience and resolve conflicts in a dynamic setting.

Some people who make serious games say that the serious application of the game should take precedence over fun. They say that serious games should offer players a safe environment to try out new behaviours. Khaled disagreed with this approach to game design. ‘Serious game experiences need to feel real and not trivial. Otherwise why would we then use them to raise a mirror to reality?’

Village Voices allows actions that teachers might find surprising. Players can be destructive in that world. They can steal from each other. The game gives aggressive players a noose with which to hang themselves. Knowing that the person whose labours you just destroyed, or who stole the items you were collecting, is sitting right there next to you intensifies the game’s emotional experience. Exchanges can become heated between players. It is these kinds of heated exchanges that often makes games fun.

Games are usually poor at provoking emotional responses. Village Voices does exactly that. Khaled told me about one session in a British classroom (the game was tested across Europe). A female student had such an upsetting experience that she cried. After reflecting on the incident with her teacher, the researcher, and the other players, the girl later returned to play again. Khaled thought this was a breakthrough learning moment for the student.

So Village Voices is a good learning tool, and it is also fun to play. But how successful was the team in applying game technologies like procedural content generation and emotion detection to its design? Khaled said that the experience of designing a game primarily for the purpose of testing technological innovations was the hardest part of the project. You might think that the role of a game designer is to work out the best solution to a problem given the technologies at hand. However, when the application of technology is the problem, the relationship between design and technology is more complex. Khaled said that the need to include particular game technologies in the design of Village Voices created a situation much like a rock band that needs to accommodate a peripheral member, such as a violin player. ‘While the violin player is not core to the project, the whole project needs to be compromised in some way in order to show off the violin player’s skills. It is not clear that the violinist is going to help the band make a new hit song, but it is clear he has to be there. So the band tries to find the violin player’s most positive qualities because he has got to be there.’

In Village Voices, the violin player’s best qualities are adaptive technologies that make the player experience more personalised. Because support for emotion detection plug-ins was never actually included in the final prototype, the game instead asks players directly how they feel about events in the game and introduces variations to the player experience according to their responses.

So far we have seen that Village Voices was successful according to the popular opinion of game-design peers at the European Serious Games — it won an award. We have also seen anecdotally that it is a provocative, if not fun game, based on the British student’s emotional response. But what does the SIREN team think about the game?

You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something

According to Khaled, it can be difficult to implement learning games in classroom settings, and even more difficult to properly evaluate them. Project funding usually runs dry after around three years, and games take most of that time to develop. Gaining access to schools is also difficult. The game is a good fit for classes like social studies that are often held only once or twice a week. Together with the problem of semester breaks and short evaluation periods, as well as the tendency for teachers to have access to only a few computers often equipped with obsolete hardware, researchers would rarely see students engage with Village Voices over a long period of time. All these things place limitations on the design, testing, and evaluation of games for research purposes.

Rigorous evaluation is important as, ultimately, learning games are not black box tools. You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something. That vital learning moment comes when players discuss their in-game experiences. As Khaled explained, ‘Playing the game is just half the experience. The other half is the subsequent discussion of the game experience.’

Given that discussion is so essential to the evaluation process, and that it is so difficult to get a sample of those discussions in a research setting, I asked Khaled if it was possible to turn the discussion into a game as well, to include it as part of the package. Khaled mentioned the meta-game, the part of the game where a player is both playing and watching themselves play the game. It is in the meta-game that players achieve the highest level of reflection. It works well as a kind of after-game discussion, a debriefing for players as they leave behind the conflicts of the game world and return to the everyday life of the school-yard; but Khaled added that of course it could be turned into a game. Achieving this level of reflection in the game package itself is just another challenge for the designers of serious games.

The Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta offers world-class postgraduate education and research in game studies, design, and technology. The inter-disciplinary team includes researchers from literature and media studies, design, computer science and human-computer interaction. Visit game.edu.mt or contact Ashley Davis (ashley.davis@um.edu.mt) for information about the Institute’s Master of Science (taught or by research) and Ph.D. programmes. This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Find out more:

-

Cheong, Y-G., Khaled, R., Yannakakis, G., Campos, J., Paiva, A., Martinho, C., Ingram, G. A Computational Approach Towards Conflict Resolution for Serious Games (full paper). In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 2011.

-

Khaled, R. and Ingram, G. Tales from the Front Lines of a Large-Scale Serious Game Project (full paper). In the Proceedings of CHI ’12, 2012.

-

Vasalou, A. and Khaled, R. Designing from the Sidelines: Design in a Technology-Centered Serious Game Project. In the Proceedings of the CHI Workshop Let’s talk about Failures: Why was the Game for Children not a Success? CHI ’13, 2013.

Some SIREN Gameplay Shots

Bees Dream of Gold

Malta has around 220 beekeepers over just 316 km2. The country’s name is tied to honey that has been prized for its flavour and health benefits. Local researchers are finding out just how unique it is and some of its powerful properties.Continue reading

NMR, Kidneys and a Family

I chose to study Chemistry and Physics simply because they were the subjects I enjoyed most, so I enrolled on a B.Sc. (Hons) degree at the University of Malta without having a clear idea about what I would be doing once the four years are over. I was not the best brain in the class but in 2004 I graduated with a 2:1 grade and it was quite obvious that I needed a plan. A couple of opportunities to embark on a Ph.D. in Britain came along through local contacts and applications on jobs websites. Despite not knowing much about the subject, I decided to go with the Ph.D. at Exeter University because it was about Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, a subject that sits right on the verge of Chemistry and Physics.

Obviously the idea of moving abroad, living away from my parents and starting this amazing new adventure was incredibly exciting. From the start of my Ph.D. things went incredibly well, it was immediately obvious that I was much better at doing research than studying for exams. I started with looking into dynamics in solid materials on the microsecond timescale, which is the less studied type of motion. It bridges the gap between very fast (spin-lattice relaxation motions, nanosecond) and slow (millisecond to second) timescales. I published my first scientific paper a year into my Ph.D., and five more followed by the time I defended my thesis.

Because of the contacts I built during my Ph.D. as soon as I finished I was offered a post at University College London, Institute of Child Health, working as a research fellow in renal imaging. I carry out research at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital using novel non-invasive Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) techniques. I work mainly with children requiring a kidney transplant. The aim of my work is to eventually be able to furnish doctors with information about their patients, which is currently either unavailable to them or they can only get through invasive clinical techniques such as biopsies. My work here has produced six peer-reviewed papers and I am currently working on a few more.

The research I carried out during my Ph.D. involved dealing with basic scientific concepts like Quantum Mechanics — that studies sub-atomic phenomena — and I was at liberty to experiment as I saw fit, which I enjoyed. However, despite being much more restrictive, I find clinical research extremely rewarding. Coming face to face with the people benefiting from all your hard work is really priceless.

Just after my Ph.D. I married my husband. We are now very proud parents of a two-year-old son. Any working mum would tell you that raising a family while maintaining a career is not easy, but I believe that if you like your job enough, combing the two is very worthwhile. Obviously research does not wait for anyone, and luckily for me, having colleagues that supported me meant that I was able to carry on publishing while I was on maternity leave.

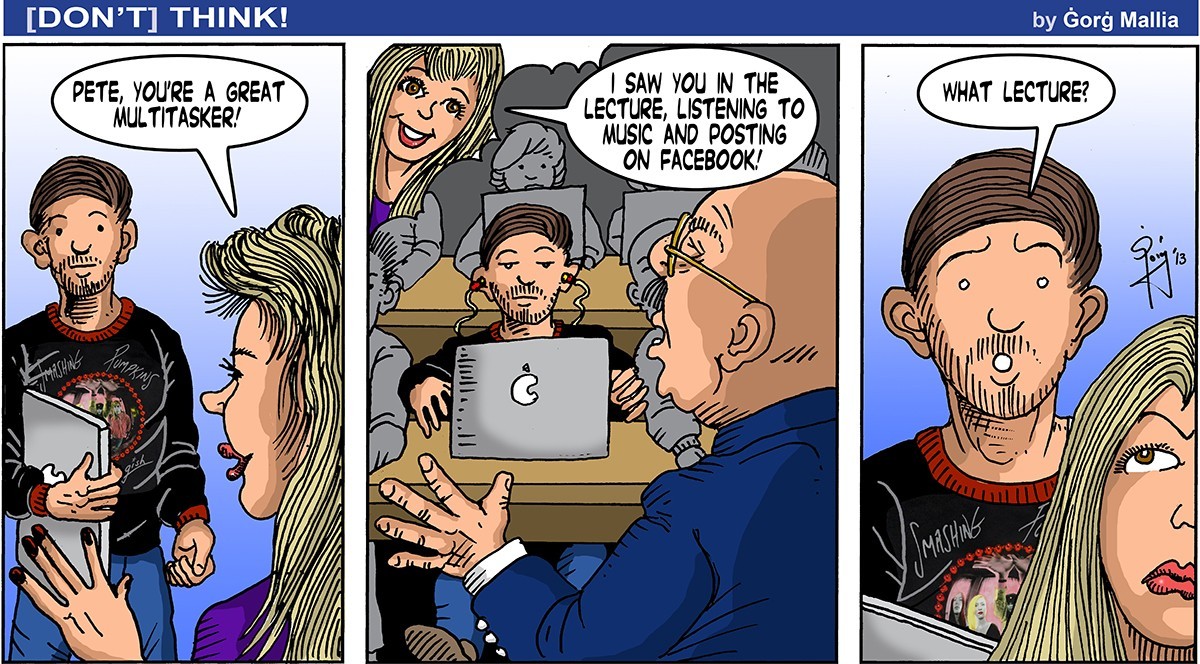

Don’t Think — March 2014 edition

What exactly is it that you do?

Research — that would be the simplest way to answer the question above. Really and truly this answer would only apply to a small niche of individuals throughout the world.

Research — that would be the simplest way to answer the question above. Really and truly this answer would only apply to a small niche of individuals throughout the world.

It is a big challenge to explain to people what you do with a science university degree. The questions “Int għal tabib?” (Are you aiming to become a doctor?) or “Issa x’issir, spiżjar?” (Will you become a pharmacist?) are usually the responses. The thing is, people have trouble understanding non-vocational careers — if you are not becoming a lawyer, an accountant, a doctor or a priest, the concept of your job prospects is quite difficult to grasp for the average Joe.

In truth, it is not really 100% Joe Public’s fault — research is a tough concept to come to terms with, ask a good portion of Ph.D. students about that. There seems to be a lack of clarity in people’s minds about what goes on behind the scenes. If you boil it down, everything we use in our daily lives from mobile phones to hand warmers are the spoils of research — a laborious process with the ultimate goal of increasing our knowledge and, consequently, the utility of our surroundings.

“People need to stop feeling threatened by big words and abstract concepts they cannot grasp”

So, then, why exactly is it such an alien concept? I think the reason is that research is very slow and sometimes very abstract. Gone are the days when a simple experiment meant a novel, ground-breaking discovery — research nowadays delves into highly advanced topics, building on past knowledge to add a little bit more. I have complained about this to many of my colleagues on several occasions — and it is more complicated when you are studying something like Chemistry and Physics, or worse, Maths and Statistics — people just do not get it!

Research is exciting. The challenge is how to infect others with this enthusiasm without coming off as someone without a hint of a social life (just ask my girlfriend). It is nice to see initiatives like the RIDT and Think magazine trying hard to get the message out there that research is a continuous process with often few short-term gains. It can be surprising when you realise how much is really going on at our University, despite its size and budget.

To befriend the general public researchers still need to do more. The first step is relaying the message in the simplest terms possible — people need to stop feeling threatened by big words and abstract concepts they cannot grasp. There also needs to be increased opportunities for interaction with research — Science in the City is the perfect example. Finally, I think MCST needs to start playing a larger role — it must work closer to University and take a more coordinated role at a national level. Only then can we begin to explain what us researchers do.

Green Chemistry for the Environment

Producing Food products, pharmaceuticals, and fine chemicals leads to hazardous waste and poses environmental and health risks. For over 20 years, green chemists have been attempting to transform the chemical industries by designing inherently safer and cleaner processes. Continue reading