Science Fiction — Mythology of the Future

Science fiction reimagines our future. Sometimes it is inspired by science; sometimes it inspires current scientists. Anna Fava visited Prof. Victor Grech at his home to talk about the mythology of science fiction and his love for Star Trek.Continue reading

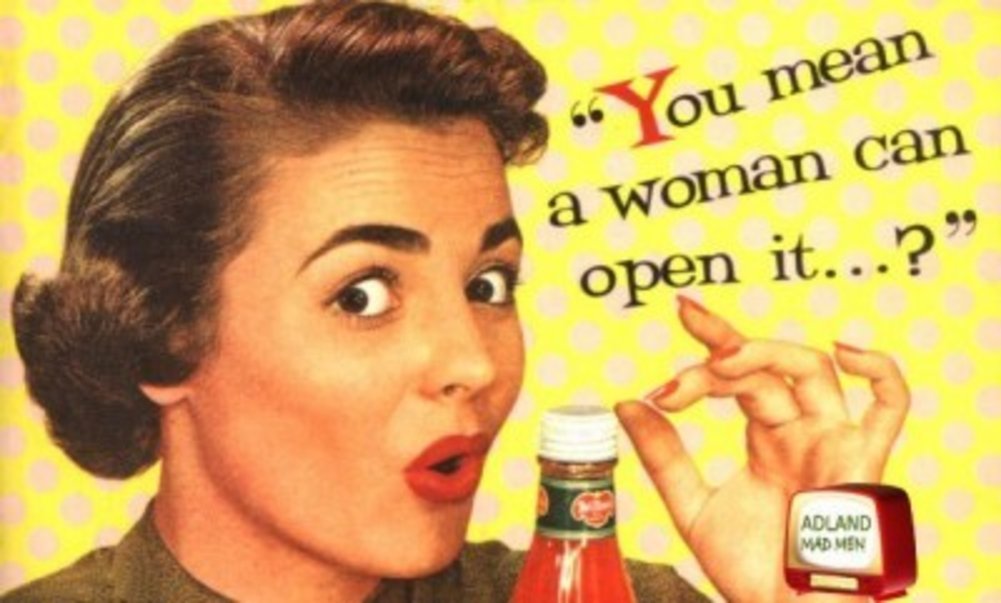

Haven’t We Had Enough of Gender Stereotypes?

An essay by linguist Deborah Cameron about gender misconceptions really hit home hard. It made me ask, why do we let gender role restrictions influence our identity. Continue reading

An essay by linguist Deborah Cameron about gender misconceptions really hit home hard. It made me ask, why do we let gender role restrictions influence our identity. Continue reading

Translating Education

Research by Jana Galea

Language,translation,and education: three hot topics on the Maltese Islands.

Malta invests heavily in education with a big chunk of its budget, strength, and efforts invested to elevate standards. Malta is also largely bilingual. This is even reflected in Malta’s constitution which places both Maltese and English as official languages. Yet, deciding on which language to use to teach children is a thorn in the side of Maltese educational institutions. A viable bilingual policy is still needed.

The European Union places great importance on national languages. This policy elevates the importance of all EU languages no matter the country’s size. The EU releases its documents in each language—a boon for Maltese translation studies. However, there is a clear lacuna in terminology and glossaries for education documents.

Jana Galea (supervised by Prof. Anthony Aquilina) translated an international publication on education into Maltese and compiled an accompanying glossary of educational terms. Translators have to adopt the role of terminologists (professionals who research and locate information or past publications to ensure accuracy and consistency in the usage of terms) when working with specialised terminology, a time consuming activity due to the lack of standardised terms. A glossary of educational terms facilitates translation by providing an easy-to-access reference tool that ensures consistent terminology in translations.

The research tries to show that Maltese and English should not be seen as rivals constantly trying to outdo each other. The Maltese language is part of the country’s unique identity, its most democratic tool, and an official EU language. It is strong and continuously growing, as Prof. Manwel Mifsud stated ‘Ilsien żgħir imma sħiħ, ilsien Semitiku imma Ewropew, ħaj u dinamiku’ (A small but complete language, a Semitic language but European, alive and dynamic). Then there is the English language which is Malta’s main linguistic link to the rest of the world and the carrier of scientific, technological, and informational developments—both languages enrich the Maltese Islands.

This research was performed as part of a Master of Arts in Translation at the Faculty of Arts, University of Malta. It is partially funded by STEPS (the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship—Malta). This scholarship is part-financed by the European Union—European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II—Cohesion Policy 2007–2013, ‘Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality of Life’.

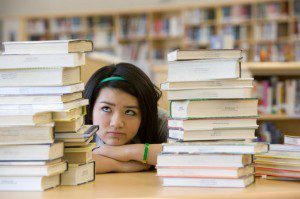

Social Wellbeing Policy at University?

University can be incredibly stressful. Staff perform high level work with plenty of academic responsibilities, while balancing a private life and leisure time. The number of students at University is rising every year. For academic and support staff this means a more intensive workload, pressure, and stress. For students it is the pressure of attaining good results, maintaining relationships, and other social and emotional wellbeing issues, such as coping with peer pressure, struggling with deadlines, and worries about the future. Numerous studies suggest that examinations negatively impact on student health and wellbeing. Some coping strategies and time management programmes have evolved at the University of Malta, for example by the University Chaplaincy. Such well-meaning initiatives are good and do good, but tend to happen sporadically and around examination time.

Many University of Malta students balance multiple identities. They often fall outside the typical demographic of an 18-year-old sixth form school leaver. Our students come from diverse socio-economic backgrounds, and may be studying full-time or part-time, with a variety of life roles: mature students, women with care responsibilities, persons challenged by disability or facing problems due to sexual orientation. Whatever the situation in life, each diverse identity places increased demands upon the students’ time and private life. These demands influence their University experiences, study perceptions, and learning style. Their peers might treat them differently due to their background.

“A social wellbeing policy will help foster confidence in its approach to academic learning, and to eliminate discrimination in favour of a more inclusive learning environment”

Besides worries about assignment deadlines and writing exams, many students are also in employment. I am not sure this trend is in line with University of Malta regulations, nevertheless, that is the situation. Students also worry about future prospects with no guarantee of secure employment after finishing their studies. So it is not only academic concerns that come in the way of student social wellbeing, and these may lead to high levels of stress, anxiety or frustration, depressed mood, difficulties with time management, procrastination, poor concentration, withdrawal from friends or family, or physical symptoms such as headaches, sleep problems, and exhaustion. University life presents numerous stress factors that may trigger off mental health difficulties.

Students experiencing stress are normally recommended psychological intervention and counselling, which may be beneficial for extremely stressed students. However, research suggests that physical activity helps improve mental health and wellbeing. The University of Malta, through its Work Resources Fund, promotes cycling through the Green Travel Plan. The initiative is more about sustainability and the environment, apart from a solution to the parking problem. However, cycling does improve our mental health and wellbeing, and is a free personal de-stressor by taking our mind off work or study, and leads to healthier lifestyle choices.

A social wellbeing policy for University will help foster confidence in its approach to academic learning, and to eliminate discrimination in favour of a more inclusive learning environment. Indeed, the principles of equality and diversity such as gender or disability are essential for a true understanding of social wellbeing, and these same principles need to be included in our University’s policy document and implemented in practice. Diversity in a dynamic, intellectual environment enriches professional and educational experiences for both staff and students.

Diversity on campus is needed and important for a healthy University. Internationally, social wellbeing on campus is being promoted through an organisational structure embedded into the ethos, culture, policies, and daily practices of a university. A social wellbeing policy includes an improved occupational health and safety system, and a commitment to address mental wellbeing, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating and substance misuse. The University needs constant commitment to positively influence the life and work of all staff and students.

The University is encouraged to guard the integrity of its communication system. Collaboration and open communication fosters conversations and relationships necessary to bring about social wellbeing. The communication process needs to be trusted and confidential for team spirit and social wellbeing. For instance, I would strongly argue for an email policy that discourages unnecessary use of bcc in emails, as the practice of not telling the original addressee is unethical and downright deceitful.

The University of Malta could establish itself as a national contact point on the European Network for Health Promoting Universities (see www.eurohpu.aau.dk). It would commit the University to place social wellbeing high on its policy agenda. A working document published by the World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe provides guidance on how to set up and develop a health-promoting university project, which would enhance and protect the social wellbeing of all staff and students.

Finally, I would also suggest an exploratory research study about aspects of university life, stress factors in teaching and learning activities, and how these impact on individual experiences. The aim is to understand the general quality of life, and how this can be improved for an informed social wellbeing policy document at the University of Malta.

This article is based on a paper Camilleri-Cassar presented at a seminar organised by the Faculty for Social Wellbeing in October 2013.

Read more here:

– Carroll, A. (2011) ‘Exploring the link between equality, diversity and wellbeing.’ In Marshall, L. and Morris, C. (eds) Taking Wellbeing Forward in higher education: reflections on theory and practice, University of Brighton Press.

– Hagarthy, D. and Currie, J. (2012) ‘The Exercise Class Experience: an opportunity to promote student wellbeing during the HSC’, Journal of Student Wellbeing, vol. 5(2):1-17.

– Hall, C., Ramm, J. and Jeffery, A. (2011) ‘Developing the University of Brighton as a Health Promoting University: the story so far.’ In Marshall, L. and Morris, C. (eds) Taking Wellbeing Forward in higher education: reflections on theory and practice, University of Brighton Press.

– UniHealth 2020: Mission Statement, www.eurohpu.aau.dk

The Mediterranean: a history to be shared

Professor Mostafa Hassani Idrissi will be one of the keynote speakers at the First Annual International Conference on Cultural Relations in Europe and in the Mediterranean, organised by the Valletta 2018 Foundation with the support of the University of Malta, which will be held at the Valletta Campus on 4th and 5th of September.

Rise of the Ancients

Over the last two decades a relatively new sort of board gaming has emerged which you might not have heard about. ‘Hobby’ or ‘modern’ board gaming is sweeping across the world.

In 1995 The Settlers of Catan by Klaus Teuber changed everything. This is the game that made many Americans realise that there is more to board games than Cluedo and Scrabble. It was family friendly, easy to get into, had a lovely trading mechanic and modular board which changed every time you played it.

Isn’t 1995 late? The ‘Spiel des Jahres’ award (basically the Oscars of Board Games) was founded in 1978. In Germany this genre of board games had been popular long before Settlers of Catan broke the monopoly of Monopoly in the US. Board games go back much further. In 2200 bc, in China, Go had already been invented.

German-style games, or eurogames, are generally regarded as one half of the two over-arching mega-genres in modern board gaming. These sort of games generally feature less luck, a more direct strategy, and less direct player interaction. Winning conditions involve collecting victory points and the design favours symbols over text.

The other half is the American-style, sometimes referred to as ‘Ameritrash’. These are generally the opposite style. War, fighting, killing, rolling piles and piles of dice (therefore luck), and player elimination.

Common themes and styles in American-style games include dungeon crawling (Descent, Claustrophobia), the American Civil War (Battle Cry), and World War II (Memoir 44).

German-style games, on the other hand, tend to have more ‘European’ cultural influences. For example, colonisation of the Americas or medieval farming are common themes (Archipelago, Puerto Rico), as are diplomacy and intrigue at the time of the Inquisition or gaining the King’s favour (Il Vecchio, Caylus).

American-style games sound similar to miniature wargaming and tabletop role-playing games (RPGs), and are definitely inspired by these earlier games. However, board games are different. A board game generally comes in a box which contains everything you need to play with a number of players and most of the time is meant to be played in one sitting. RPGs and wargaming do not follow these rules.

Interestingly, American and German-style games developed in more or less the same period of time in two completely different cultures. This is comparable to the development of the Japanese RPG and the Western RPG in video games.

And today?

Board games are experiencing a golden age. If you had come into the hobby a mere five years ago, the picture was simple. But the worldwide Indie revolution and crowd-funding has also hit board games.

Until a few years ago a few recognisable, high profile game publishers dominated the market. Euro and American style games were easily separated. Now, board games are becoming less and less of a niche hobby. New designers are creating games that combine many different influences from past games. The lines are being blurred. More experimental games and publishers are starting to pop up thanks to crowd-funding, and virtually anyone can publish a game.

In Malta, one of the first locally developed modern boardgames will be published internationally next year — watch this magazine — and others are in development. Exciting times.

David Chircop (and Yannick Massa) topped the Board Game Geek Hotness List for a week and won Best Board Game award at Malta’s first Global Game Jam held on January 24–26, 2014 at the Institute of Digital Games, UoM. See http://maltagamejam.com for next year’s Game Jam or take a course at the Institute http://game.edu.mt to learn how to make your own game. This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Bridging the Gap

My career has taken me from industry to research, with a 3-year stint as a business consultant, and EU and local fund evaluator for R&D projects. Now I am back at university managing the consultancy, laboratory services, and training business within the Malta University Consulting Ltd (MUC). The University of Malta (UoM) encourages its staff to engage in activities like these through the MUC. Through this article I hope to encourage UoM staff and outside entities to meet us to talk about their opportunities.

The MUC is one of the subsidiary companies of the UoM that we are revamping. Our new office is located on Campus in the same building as the Knowledge Transfer Office and the Business Incubator TakeOff. Our doors are always open for both academic and technical staff, as well as industry and public entities.

Having carried out research at the UoM and visited foreign research organisations, I have witnessed the UoM develop into a hub of knowledge, resources, and excellence competitive with research institutes abroad. Staff members have expertise in a wide range of areas and can offer technical, educational, business, and scientific advice. Expertise ranges from environment and energy, to sciences, education, engineering, ICT, finance, health sciences, and other areas. The quality of the work is highly professional and competes very well with international levels.

The MUC’s role is to facilitate staff by taking care of the administrative, financial, legal and marketing issues related to networking with industry, allowing them to do what they are best at: deliver the expertise efficiently. Staff and entities are given support to find opportunities and set up teams of experts when projects are multidisciplinary. Projects are managed from their inception to closure — from the preparation of proposals and submission of quotes to chasing deliverables and deadlines. The MUC helps with contract negotiation and legal document preparation for the necessary agreements. It provides insurance coverage and manages the issuing of invoices, and securing and processing payments.

Over the past nine months, with my new role at the MUC, we have been working with a number of local public entities and SMEs (Small to Medium Enterprises) on a number of projects. We have worked on small one-off services that require biological, physical, mechanical, and electrical laboratory tests and larger longer-term projects such as chemical tests with the pharmaceutical industry. Contract research and consultancy projects are generally bigger projects involving teams of experts. We have been involved in projects in the telecommunications, ICT, education, renewable energy, and electronics industries. We also organise Continuous Professional Development (CPD) courses such as digital gaming, Horizon 2020 EU funding, and e-marketing.

We can do much more than we are doing. Our vision is to keep growing slowly but steadily involving other members of staff and other entities. Do contact us — our doors are always open.

Dr Ing. Alexia Pace Kiomall can be contacted on alexia.pacekiomall@muhc.com.mt or 2340 8903

The School of Games

In ancient times games played an integral role in society. Whilst in today’s hyperlinked world, games have evolved into complex, sophisticated mechanisms that enthral millions. Now, however, games are dismissed as trivial, and of no real value. But is this really the case? Cassi Camilleri meets the research team gamED from the University of Malta to find out.

Why so Serious?

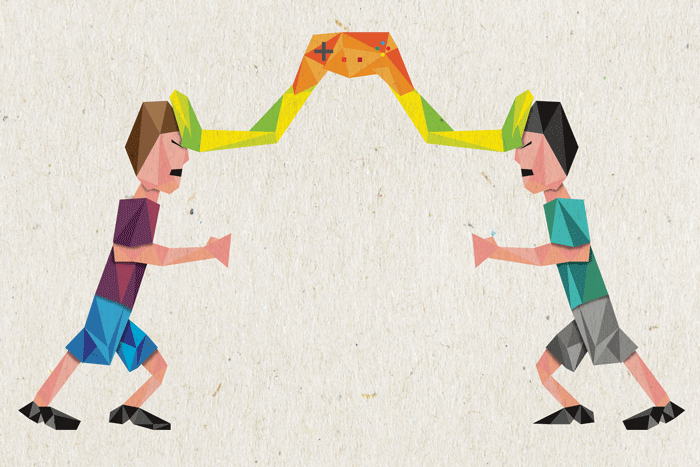

How do you help school children handle fights, bullying, and other conflict properly? You build a game, of course, and you let children take on different roles in a village. But how does that lead to resolving conflicts? Ashley Davis met researchers Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis to find out more

Do you chuckle at the thought of a serious game? The phrase is an oxymoron. How can a game be serious? Games are meant to be fun, frivolous, a way to pass the time. Or else you sometimes hear that games are anything but frivolous. That video game violence in particular is a threat to social order. The idea that games can be used to advance human understanding about the world, and that they can help us to teach, train, or motivate people in some way, is something that still needs to enter our mentality.

Designing games to explore research questions and to solve real world problems is actually a very important aspect of games research, an area of applied research that now has a strong presence at the University of Malta with the establishment of the Institute of Digital Games. Researchers from the Institute work on European-funded projects to create games that tackle serious problems affecting children and adults alike.

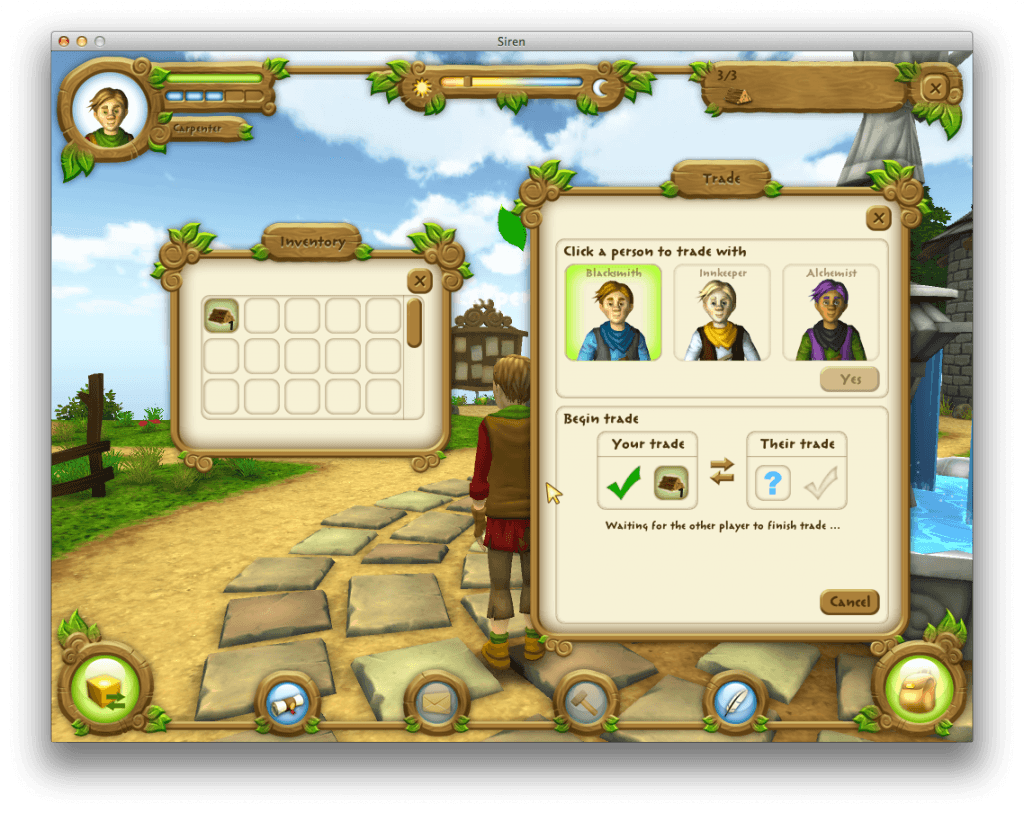

Village Voices has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards

Prof. Rilla Khaled and Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis are two researchers now based at the Institute of Digital Games who work on serious game projects. Khaled’s work focuses on serious game design, while Yannakakis is a specialist in artificial intelligence and computational creativity. Computational creativity tries to build upon the latest technological innovations in human–computer interaction that enable computers to act intelligently to some aspects of human beings. These two areas, game design and game technology, represent a large part of the teaching and research strengths of the Institute.

One game that Khaled and Yannakakis recently helped develop is Village Voices which has been voted the best learning game in Europe at the 2013 Serious Game Awards. It was developed as part of the SIREN project, an FP7-funded interdisciplinary consortium made up of researchers from Malta, Greece, Denmark, Portugal, the UK and the US, along with Serious Games Interactive, a Danish Games Studio.

Let’s take a look at what makes a serious game and think about what made the project a success and what didn’t work so well.

The serious side of Village Voices aims to help school children learn conflict resolution skills. Players take on the role of one of four interdependent villages that are situated in a farm setting and given various quests to complete. Sitting side-by-side at separate computers, they may collaborate, share resources and help each other, or they may spread rumours and steal from each other. Much like any playground setting, children can play nicely, or they can be bullies.

The purpose of the SIREN project was to apply the latest advancements in game technology to the creation of serious games. The brief focused on innovations in procedural content generation, an area of artificial intelligence that automatically builds game elements like game levels or quest structures that would otherwise need to be designed manually. Another part of this innovative technology is detecting the emotions of players. Physiological responses can be measure through various tech like Electroencephalographic (EEG) sensors that can be used to detect a person’s emotional state directly by reading their brain’s electrical signals. Virtual agents were another technology that interested the research team. These agents are believable non-player characters that interact with the player with perceived intelligence.

The idea was to then create a game that would adapt to player behaviour, using emotion recognition tools to create an individual experience for each player. The decision to focus the game on teaching children about conflict resolution came later. Rather than to create a game about bullying behaviour, which is what a lot of people think of when they picture conflict between children, the research team wanted to explore the kinds of everyday conflicts that take place in school-yards. Friendship disputes, differences in opinion, and arguments over the possession of classroom items might seem trivial to adults, but they are important problems for children for whom school is their entire world. The SIREN consortium envisioned a game where players could experience and resolve conflicts in a dynamic setting.

Some people who make serious games say that the serious application of the game should take precedence over fun. They say that serious games should offer players a safe environment to try out new behaviours. Khaled disagreed with this approach to game design. ‘Serious game experiences need to feel real and not trivial. Otherwise why would we then use them to raise a mirror to reality?’

Village Voices allows actions that teachers might find surprising. Players can be destructive in that world. They can steal from each other. The game gives aggressive players a noose with which to hang themselves. Knowing that the person whose labours you just destroyed, or who stole the items you were collecting, is sitting right there next to you intensifies the game’s emotional experience. Exchanges can become heated between players. It is these kinds of heated exchanges that often makes games fun.

Games are usually poor at provoking emotional responses. Village Voices does exactly that. Khaled told me about one session in a British classroom (the game was tested across Europe). A female student had such an upsetting experience that she cried. After reflecting on the incident with her teacher, the researcher, and the other players, the girl later returned to play again. Khaled thought this was a breakthrough learning moment for the student.

So Village Voices is a good learning tool, and it is also fun to play. But how successful was the team in applying game technologies like procedural content generation and emotion detection to its design? Khaled said that the experience of designing a game primarily for the purpose of testing technological innovations was the hardest part of the project. You might think that the role of a game designer is to work out the best solution to a problem given the technologies at hand. However, when the application of technology is the problem, the relationship between design and technology is more complex. Khaled said that the need to include particular game technologies in the design of Village Voices created a situation much like a rock band that needs to accommodate a peripheral member, such as a violin player. ‘While the violin player is not core to the project, the whole project needs to be compromised in some way in order to show off the violin player’s skills. It is not clear that the violinist is going to help the band make a new hit song, but it is clear he has to be there. So the band tries to find the violin player’s most positive qualities because he has got to be there.’

In Village Voices, the violin player’s best qualities are adaptive technologies that make the player experience more personalised. Because support for emotion detection plug-ins was never actually included in the final prototype, the game instead asks players directly how they feel about events in the game and introduces variations to the player experience according to their responses.

So far we have seen that Village Voices was successful according to the popular opinion of game-design peers at the European Serious Games — it won an award. We have also seen anecdotally that it is a provocative, if not fun game, based on the British student’s emotional response. But what does the SIREN team think about the game?

You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something

According to Khaled, it can be difficult to implement learning games in classroom settings, and even more difficult to properly evaluate them. Project funding usually runs dry after around three years, and games take most of that time to develop. Gaining access to schools is also difficult. The game is a good fit for classes like social studies that are often held only once or twice a week. Together with the problem of semester breaks and short evaluation periods, as well as the tendency for teachers to have access to only a few computers often equipped with obsolete hardware, researchers would rarely see students engage with Village Voices over a long period of time. All these things place limitations on the design, testing, and evaluation of games for research purposes.

Rigorous evaluation is important as, ultimately, learning games are not black box tools. You cannot sit a child down in front of a computer and hope that they will magically learn something. That vital learning moment comes when players discuss their in-game experiences. As Khaled explained, ‘Playing the game is just half the experience. The other half is the subsequent discussion of the game experience.’

Given that discussion is so essential to the evaluation process, and that it is so difficult to get a sample of those discussions in a research setting, I asked Khaled if it was possible to turn the discussion into a game as well, to include it as part of the package. Khaled mentioned the meta-game, the part of the game where a player is both playing and watching themselves play the game. It is in the meta-game that players achieve the highest level of reflection. It works well as a kind of after-game discussion, a debriefing for players as they leave behind the conflicts of the game world and return to the everyday life of the school-yard; but Khaled added that of course it could be turned into a game. Achieving this level of reflection in the game package itself is just another challenge for the designers of serious games.

The Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta offers world-class postgraduate education and research in game studies, design, and technology. The inter-disciplinary team includes researchers from literature and media studies, design, computer science and human-computer interaction. Visit game.edu.mt or contact Ashley Davis (ashley.davis@um.edu.mt) for information about the Institute’s Master of Science (taught or by research) and Ph.D. programmes. This article forms part of The Gaming Issue.

Find out more:

-

Cheong, Y-G., Khaled, R., Yannakakis, G., Campos, J., Paiva, A., Martinho, C., Ingram, G. A Computational Approach Towards Conflict Resolution for Serious Games (full paper). In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 2011.

-

Khaled, R. and Ingram, G. Tales from the Front Lines of a Large-Scale Serious Game Project (full paper). In the Proceedings of CHI ’12, 2012.

-

Vasalou, A. and Khaled, R. Designing from the Sidelines: Design in a Technology-Centered Serious Game Project. In the Proceedings of the CHI Workshop Let’s talk about Failures: Why was the Game for Children not a Success? CHI ’13, 2013.