Delicious delivery for your muscles

It is challenging enough to keep a workout routine, let alone cook nutritious, varied meals at the same time. What if sporty people could have unique meals delivered to their door? Marija Camilleri meets a team that fills this business niche and fitness enthusiasts’ stomachs.

Continue reading#MeTooSTEM: We must do more to protect women

You can have all the role models in the world. You can enjoy grants and empowerment seminars. Yet when a senior colleague you’ve always looked up to corners you, all you want is to run away, fast. Cassi Camilleri writes.

The heightened awareness around equality and representation has reached Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields. The global effort to recruit more women and girls into industries traditionally described as male-dominated is yielding results. In 2017, women outnumbered men in the Psychology, Pharmaceutical Science, and Biology undergraduate programmes at the University of Malta (UM). However, increasing the numbers of women is paving the way to a whole new, and yet despairingly old, battle. Many who brave becoming a minority in their profession report having to face numerous barriers. Sexual harassment is one of them.

Jennifer (not her real name) had big dreams when she first entered the field, and continues to uphold them, but it has not been easy. She didn’t see red flags in the ‘friendliness’ of a new project colleague, until he crossed boundaries. ‘I had a colleague who was much more established than I am, and every now and then he would make throwaway sexual comments. This was all supposedly in the spirit of “joking around”. But I think when you have a position of authority, you have to be even more careful about the comments you make. Your subordinates are not really in a position to make their discomfort known,’ she says. Reporting this behaviour is difficult in closely knit teams, like innovative startups, laboratories, or teams sharing grant funding.

Sexual Harassment Isolates

Jennifer felt all alone in this, but sexual harassment in the workplace is a known issue in Malta. According to research conducted by the NGOs Men Against Violence and the Women’s Rights Foundation, three out of every four female respondents reported experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace.

‘Many of respondents to our survey who had reported instances of sexual harassment said that they were silenced in some way, usually by being ignored, not taken seriously, but sometimes they were even demoted or threatened with dismissal,’ says Aleksander Dimitrijevic, founder and president of Men Against Violence. Internationally, the movement to expose STEM-specific patterns of sexual harassment became known as #MeTooSTEM. In 2018, the US’s National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) published a damning report titled Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The research showed that ‘[w]omen in STEM endure the highest rate of sexual harassment of any profession outside of the military.’ It also stated that ‘[n]early 50% of women in science, and 58% of women in academia, report experiencing sexual harassment, including 43% of female STEM graduate students.’

I think when you have a position of authority, you have to be even more careful about the comments you make. Your subordinates are not really in a position to make their discomfort known.

‘When my colleague found out that I was in a relationship with another woman, he started making comments about how attractive my partner was and how she couldn’t possibly be gay. As a member of the LGBTQ+ community, I found this very jarring,’ Jennifer tells. Just how many young women share her experience is not known, as local research is sparse, and looking for stories on social media was challenging because each unique testimony risks exposing the survivor.

The fight against sexual harassment needs institutional structures in place to handle such cases. The UM has been at the forefront of this since the early 1990s, according to Dr Maureen Cole (Faculty for Social Wellbeing), an advisor appointed to support the UM’s efforts to quash sexual harassment and help victims achieve resolution. ‘Thanks to the efforts of the Gender Issues Committee, the University of Malta has had a sexual harassment policy in place since 1994,’ she explains, noting that this preceded national legislation. ‘There were times when one of the [local] banks looked to us for guidance and advice in the late 90s. It was, and is, a clear commitment from the Rectorate to make sure people are protected. The University should be given some recognition for this. I feel that it is important to recognise good practice,’ Cole asserts. This openness is notable, as messages to human resources staff at other relevant institutions were left unanswered.

Are people like Jennifer using these services? Cole reports that the number of sexual harassment reports made at the UM per year average between one and two in an institution with 11,500 students and nearly 1,600 members of staff (latest published data). Cole admits, ‘It is a low number.’

Communities of silence

The fearful climate poisons the work environment. ‘It made me feel like it was no longer a professional environment, and it was isolating. I had to politely laugh off the comments because I didn’t want to damage a professional relationship I knew was important to my career. The sad thing is I know I’m not the only one, and it makes me feel guilty not speaking up when I hear there are others,’ says Jennifer.

Academia’s hierarchical structures lend themselves easily to abuse of power. The NASEM report revealed that ‘90% of women who report sexual misconduct experience retaliation.’ Malta’s small size and hugely connected networks makes this even more of a threat to those considering speaking up. Cole highlights this point in her lectures. ‘I say to my students, imagine if I were the harasser. I’m teaching you here at University. There were times when I was on the social work profession board. So you’re coming to apply for a warrant, and I’m sitting on the same board. I’m an advisor to this person and that person. You can’t get rid of me. Because Malta is what it is. […] If you’re a lawyer, you’re going to be encountering these people. […] If you’re a medic, you’re going to be in the same hospital. I’m not saying people shouldn’t report, but I understand why they don’t.’

The sad thing is I know I’m not the only one, and it makes me feel guilty not speaking up when I hear there are others

‘On this occasion, the reports and comments made against my colleague were acknowledged by my team when I brought them forward, but it was difficult. I knew that I would still have to work closely with this person,’ says Jennifer. ‘Communities at this level are tiny and people bump into each other all the time. My network and my prospects could have suffered significantly if my other colleagues did not receive the complaints as well as they did. And I’m grateful for that.’ Finding a safe space feels more urgent than seeking justice. Sending an anonymous message to the popular Women for Women group feels more urgent than describing very personal encounters in a formal report.

The current reality is that when a report comes to the Sexual Harassment Advisors, anonymity cannot be afforded for very long. ‘We cannot investigate [a complaint] without seeing the other person’s side of the story according to the regulations,’ says Dr Gottfried Catania, also a sexual harassment advisor at the UM. ‘The other side has to be made aware of the accusation, Cole continues. ‘There will be a point where the accused will receive a report saying this person is making this report about your behaviour. And many times, even people who come very determined to take action do not go forward once they realise that.’

Speak up Malta

Dr Lara Dimitrijevic (Department of Gender Studies) has a lot to say about the shame surrounding sexual harassment, not only in STEM but in Malta as a whole. ‘We have a culture of dissuading people, silencing people. Malta has a very high percentage of the population that believe that women make up stories. I find this very shocking.’ According to data from the research quoted earlier, a third of all respondents believed that victims of sexual harassment were partly to blame due to the way they dressed or behaved. Victim-blaming is clearly still pervasive. ‘The reporting for sexual harassment to the National Commission for the Promotion of Equality has decreased from three cases in 2015, to zero in 2016, to zero in 2017, to just one in 2018. Does this mean sexual harassment isn’t happening in Malta? No. Of course not. It’s that people are not speaking out. While awareness is increasing, we feed into the victim blaming and we’re not addressing that at all.’

‘The only way to deal with sexual harassment at [the] workplace is for [a] company to take [a] pro-active approach: create policies and [a] clear reporting system, inform every new employee on their first day about it, have [the] policy printed and hanged on the walls of the offices, have HR department organise training, Aleksander Dimitrijevic suggests.

Innovation binds all STEM disciplines. Without fresh minds, innovation stops. We stop creating new solutions for the problems our societies continue to face. We owe it ourselves, to our communities, and to those taking the helm, to provide safe spaces and break the silence.

What does sexual harassment look like?

According to the Code of Practice compiled by the Maltese National Commission for the Promotion of Equality for Men and Women (NCPE), sexual harassment at the workplace is defined as ‘unwelcome sexual conduct’ and is unlawful under the Equality for Men and Women Act, 2003 (Cap 456) and under The Employment and Industrial Relations Act, 2002 (Cap 452).

Sexual harassment may take many different forms and can involve:

- unwelcome physical contact such as touching, hugging, or kissing;

- staring or leering; suggestive comments or jokes;

- unwanted invitations to go out on dates or requests for sexual interaction;

- intrusive questions about an employee’s private life or body; unnecessary familiarity;

- insults or taunts based on your sex;

- sexually explicit emails or messages;

- sexually explicit pictures, screen savers or posters;

- behaviour which would also be an offence under the criminal law, such as physical sexual assault, indecent exposure, and obscene or pornographic communications.

Sexual harassment procedures at UM

The procedures to deal with sexual harassment at UM start when the sexual harassment advisors meet the person reporting sexual harassment to listen to their account of the incident/s. From here, the advisors provide information on other support services available at the university and nationally, and offer referrals as needed.

The next stage is making a decision about the action to take. The informal route involves a written agreement signed by the complainant and the alleged harasser as a form of assurance that the behaviour is not repeated. The formal route involves a report being made to the police and potential disciplinary action being taken.

STEMming gender gaps

In an equal society, men and women would be drawn to various careers in roughly similar numbers. The fact that there are still so few women in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields shows that something is crooked in the recruitment and retention of students and staff. Danielle Martine Farrugia writes.

As a young girl, I was always curious to understand the world around me, constantly asking questions and conducting mini-experiments. The world was my oyster — nothing was off limits. A pivotal moment was when the 12-year-old me chose to profile the accomplished scientist Marie Sklodowska Curie for a school project. A physicist, chemist, wife, mother, and the only person to receive two Nobel prizes — in Physics and in Chemistry — she is the best-known female researcher who jumped through hoops to be given the same opportunities as male colleagues.

I began to understand the trepidation she overcame to further her education. I saw how she surpassed obstacles in a male-dominated environment. At this point in my life I was not aware of what women had to endure to move forward and conduct scientific research. However, by reading up on and speaking to female researchers and scientists, I realised that reality was far from balanced. Running Malta Cafè Scientifique, our team committed to finding at least one female speaker each year, but even that was difficult, as women are not that visible in research. The experience motivated me to have a panel discussion on the gender gap in STEM at a Malta Cafè Scientifique event.

The European Commission defines the gender gap as a disparity between men and women in any social, political, or cultural area, which results from different participation levels, access, rights, and remuneration. Studies cited by The Conversation revealed that journal editors are less likely to commission work from female scientists. When applying for postdoctoral fellowships, women received ‘lower competence ratings than men who had less than half their publication impact’. In the words of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani activist for female education and the youngest Nobel Prize laureate, ‘We cannot all succeed when half of us are held back.’

Our team committed to finding at least one female speaker each year, but even that was difficult, as women are not that visible in research.

There are no grounds for different participation levels in STEM. In Malta, girls score significantly higher than boys in science, according to the international PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) survey of 15-year-olds, measuring their skills in reading, science, and mathematics. Despite women’s good exam results, four out of five graduates in computing and engineering are male across the EU (as of 2012). This trend is consistent worldwide, especially at the University of Malta (UM), where student undergrad statistics from 2018/2019 show that STEM graduates are overwhelmingly male-dominated (engineering — 85% and ICT — 86%), except for health sciences (76% female), dental surgery (64% female), and medicine and surgery (60% female).

‘Research shows this has a lot to do with social belonging and the belief in one’s [chances to] succeed. This means that in order to attract more girls to study STEM subjects and enter STEM careers, we need to address the stereotypes they are exposed to, and we need to do this as early as possible,’ says Irene Mangion, Programme Developer at Esplora Interactive Science Centre. UM psychology graduate Gillianne Saliba explored this gap in Malta in her undergraduate study, ‘Women in STEM: A qualitative study on women’s experiences’. She found that female undergraduates pursued STEM courses when they were exposed to STEM subjects early on and when they found a structure to support them.

Building on these principles, the Ministry of Education initiated Teeny Tiny Science Café and the National Science STEM expo at Esplora, engaging Malta’s main higher education institutions. ‘Engaging women in STEM outside of the formal academic structure is essentially democratising women’s voices within the community,’ believes Simone Cutajar, chairperson of GreenHouse, a local citizen science NGO. Through such experiences, citizens are given the opportunity to see whether they would like to pursue science as a career.

Defining career moments should not depend on individual luck.

Supportive mentors and role models, male or female, are crucial. Dr Claudia Borg from the Faculty of ICT (UM) considers herself lucky to have found men who believed in her capabilities and supported her in the advancement of her studies and career. But defining career moments should not depend on individual luck. To structure the access to mentors, the ‘Women in Science — Bridging the Gap’ project is building a mentorship structure to offer female role models to students.

‘From an early age, our education system informs our upcoming generations about male scientists,’ the project’s manager Karen Fiorini believes. ‘Their achievements are hailed as admirable, life changing events, which is great. Unfortunately, however, the failure to mention female scientists’ accomplishments is stripping children of female role models.’ Run by the Malta Chamber of Scientists and funded by the Voluntary Organisations Project Scheme of the MaltaCVS, a national council of nonprofits, this scheme will reach out to children aged 6–11, sixth formers, and adults. Using interactive performances and interesting activities, the project’s team will bring Maltese female researchers and their work to the fore.

In the words of Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani activist for female education and the youngest Nobel Prize laureate, ‘We cannot all succeed when half of us are held back.’

So far we have covered recruitment and mentoring. But why do established, competent women leave STEM careers in droves? We need more Malta-focused research to understand this complex issue. By awarding the Equality Mark to organisations that prioritise gender equality, the National Commission for the Promotion of Equality is encouraging tech companies to create a safe space for both genders to work harmoniously side by side. Tech professionals are rising to the challenge. Vanessa Vella, a Senior Software Engineer working as a full-stack web developer at CS Technologies, co-founded and co-chaired an NGO called MissInTech to introduce more women to technology.

All these local changemakers are working hard to reform recruitment, career development, and staff retention. Is that enough? We invited some of them to discuss this at the Malta Café Scientifique event ‘Women in STEM,’ supported by Pro-Rector for Student & Staff Affairs and Outreach Prof. Carmen Sammut. Inspired by my younger self and that simple school project, the Malta Café Scientifique team is drafting a set of recommendations for institutions following the panel discussion. STEM fields cannot afford to continue bleeding talented women.

Further reading:

Fine, I. and Shen, A. ‘Perish not publish? New study quantifies the lack of female authors in scientific journals.’ The Conversation, 8 March 2018.

How linguistics helped me power up my language

‘If you are a woman working in a traditionally male hierarchy, you have one of two choices: Quit or Masculinize’. Linguist Prof. Lydia Sciriha chose to end her keynote speech at the HUMS symposium with this quote from Pease and Pease (1999). As a curious scientist and keen observer of society, she has accumulated a plethora of personal stories to show how communication gaps solidify gender inequality. She shares them here with Daiva Repeckaite.

Continue readingDaphne, my friend

She is hated by people who didn’t know her. She is also hugely admired by people she didn’t know. Prof. Clare Vassallo shares a deeply personal tribute to world-renowned murdered journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

Continue readingWalking Malta: #unsafe or #vibrant?

Author: Carlos Cañas Sanz

Have you ever found yourself on a busy road framed between cacti and fast cars, because Google Maps thought it would be a good walking path for you? To avoid such situations, we need local research and solutions on Malta’s walkability issues.

Continue readingWomen’s baroque male allies

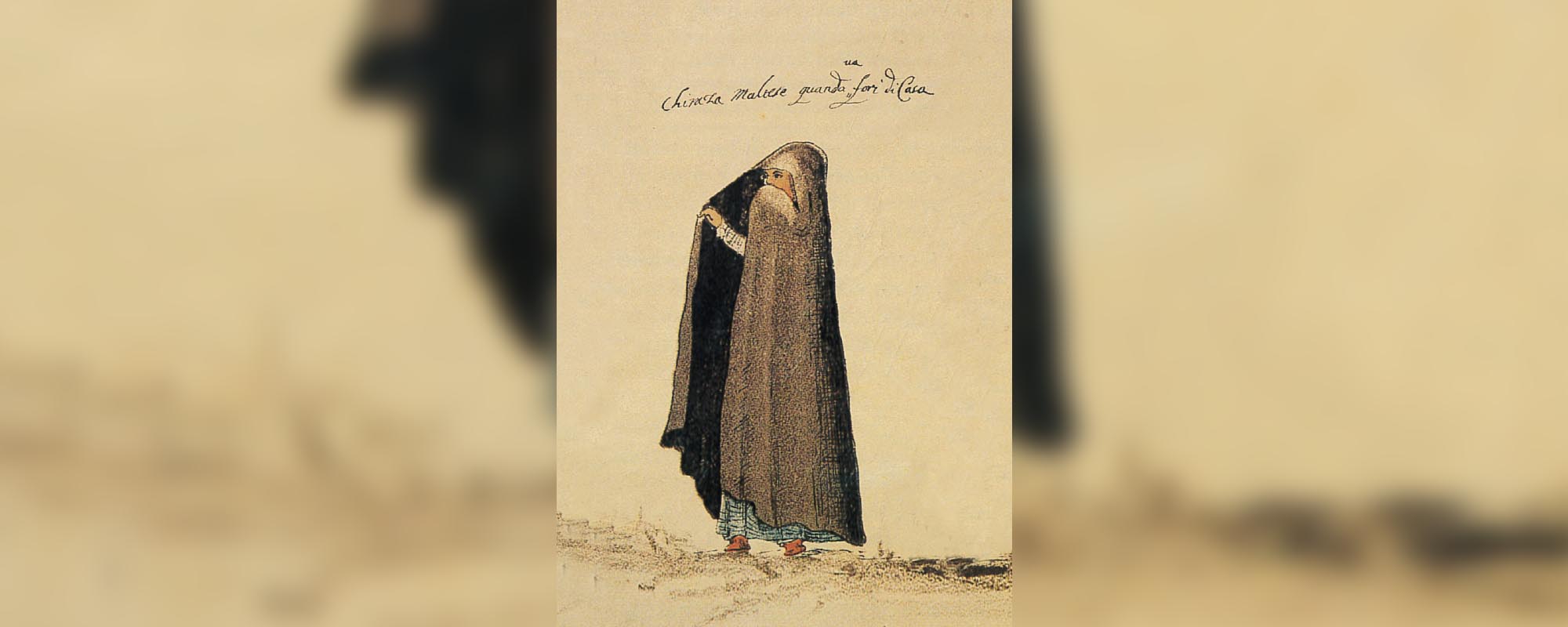

In early modern Malta, some men resisted patriarchal attitudes which oppressed women. Drawing upon two cases lifted from primary sources, Dr Christine Muscat argues that written history has largely neglected the voices of men who manoeuvred patriarchal structures to empower women.

Continue readingWhen your job captures ‘every breath you take’

Are you a doctor? A friend? A mother? An athlete? All of the above? Kieran Teschner talked to Dr Patricia Bonello from the Department of Social Policy and Social Work (University of Malta) about the relationship between people and their profession, and how music can capture this relationship.

Continue readingYoung motherhood is not all doom and gloom

Author: Dr Andreana Dibben

Teenage mothers are all too familiar with the phrase ‘children raising children’. From professionals to politicians, media, and even strangers on the bus, everybody has something to say about the perils of teenage pregnancy. Yet, when I spent two years attending a weekly mother and baby support group, hanging out with 24 young mothers (ages 13 to 21) for my doctoral research, I learnt that the reality was much more complex than a clichéd slogan.

My research looked into the lived experiences of pregnant young women and young mothers in Malta, specifically capturing detailed insights into how participants defined their sexual, reproductive, and mothering choices in the context of the policies, services, and discourses that framed their lives. Many participants considered being a mother as a deeply positive experience. Knowing full well about the teen motherhood stigma, they reclaimed the pejorative phrase ‘children raising children’ and saw their young age as advantageous because ‘you and your child grow together’. They felt they had more physical energy to carry out motherhood-related tasks, and expected a better mother-child bond due to a minimal generation gap.

What impressed me was that teenage mothers know how to care. The level of attentiveness and the responsibility with which young mothers cared for their children starkly contrasted with society’s stereotypes. Many participants had assumed caring roles and responsibilities from a young age, so caring for children was something they had learnt to do early on.

Pregnancy was not always accidental as is publicly presumed. It was often an active choice, framed as a positive step towards family formation. Research participants saw their early romantic relationships, often with older men, as an expression of psychological maturity. Some claimed the baby was healing the sufferings of their difficult childhood.

There is no denying that some pregnancies were not planned. Often, this was due to imbalanced power in relationships and control over sexuality. ‘We didn’t use condoms because he did not want to’ or ‘he did not want me to go on the pill as he saw it as a free pass to screw around’ were common phrases in the interviews.

The feminist lens helps detect gendered and class-based attitudes and behaviours, particularly conspicuous in the young mothers’ stories. Popular culture’s heterosexual imagery shapes young women’s reproductive choices early on. Framed by this ideology, the creation of a nuclear family is seen as the ultimate goal of a romantic relationship. Even for unplanned pregnancies, an ethic of responsibility and the stigma on abortion further pressure them towards choosing motherhood. Mothers are then expected to be completely selfless in their ‘sacred’ role. As Mireille, an 18-year-old mum who accidentally got pregnant at 15, put it: ‘I used to feel from the start that a huge responsibility was coming upon me. Now I’m not sorry that I had her though… In the end you do everything for your children.’

Yet my research shows that young mothers are not passive in this process. Choosing motherhood in the unequal context they inhabit, young mothers take their lives in their own hands. They challenge the patriarchal ideology that values only certain kinds of motherhood as ‘good’ — it must be based on marriage, economic independence, and a mature biological age. Most young mothers made active decisions when faced with dominant male partners, patronising professionals, and stigmatising incidents. Motherhood may have exacerbated disadvantage in many situations, but it also gave a sense of empowerment.

This study shed light on how young mothers valued their experience over social, economic, and cultural constraints. They consider motherhood as a positive life choice rather than a limitation. In the words of Isabel, a 19-year-old mum of a two-year-old: ‘The most important thing is how you feel inside. I feel great joy and satisfaction. Even though you’re 16, you can still raise your kids well. And that’s what matters at the end of the day.’

Isabel’s message is clear: Young mothers are making a valuable contribution to society. Instead of pity, they need respect and support.