My work centres on the co-existence of dualities. It treads blurred borders and investigates uncertain divides between opposing poles. It synthesises extremities and acts as a seam that binds together disparate realities.

Uncertain of its own actuality, it questions its own being.

Artist statement

De-isolating an island scene

While the Maltese art scene continues to expand and mature, questions of relevance are coming to the fore: How does Maltese art travel? Is it as insular as we think? Nikki Petroni looks at current research to find answers.

Text feeds text, feeds art

Cassi Camilleri goes on a rollercoaster ride into the relationship between the Humanities and film with Prof. Gloria Lauri-Lucente and Dr Fabrizio Foni. Together, they unpack the debate on film adaptation and points of origin.

So you think you can’t dance?

Stalking the President, fundraising, and improving people’s lives through dance is all in a day’s work for Step up for Parkinson’s founder Natalie Muschamp, as Dawn Gillies finds out.

Of art and interpretation

Interviewed by Prof. Raphael Vella, local artist Aaron Bezzina gives insights into what has shaped him and his work.

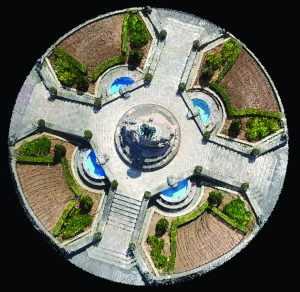

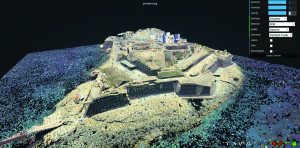

Mapping in 3D

Drones have rapidly gained popularity in recent years. They are now commonly used by photographers and videographers, law enforcement, the military, and criminologists. At the University of Malta (UM), they are being used as a part of CloudIsle.

CloudIsle, a project headed by Prof. Saviour Formosa (Faculty for Social Wellbeing, UM), is using drones kitted out with laser scanning tools, ground-penetrating radar, and surveying equipment to create 3D maps of Malta. Using billions of data points, the fine details of above and below-ground features can be recorded. This includes precise detail on buildings, as well as the intricacies of the island’s labyrinth of underground caves. The technology will even be used to uncover underwater artefacts at up to 500m depth. The legendary Um El-Faroud and the Xlendi-Karwela-Cominoland trio of wrecks, now transformed into artificial reefs and popular diving sites, are currently under review.

This data’s real-world applications are vast. It can be used to aid Malta’s Planning Authority and ensure building stability, as well as analyse extreme weather and monitor climate change. The Department of Criminology (Faculty for Social Wellbeing, UM) is also employing these tools in environmental enforcement, as well as for spatial forensics and crime reconstruction in scenes related to bombings and homicides.

CloudIsle is already reaping rewards. The team has discovered and named the Għariebel doline land feature off the Selmunett Islands. They have also created a baseline map of Malta and its seas that can be used to integrate new 3D spatial data.

Author: Professor Savoiur Formosa

Are we ready for self driving cars?

In 2016 a 40-year-old technology company owner called Joshua Brown was killed when his autopiloting Tesla Model S malfunctioned. Since then a number of other incidents have raised the problem of safety in and around autonomous cars. One potential solution is to connect cars together so that they can keep in constant touch, letting each other know exactly where they are and when to get out of the way. Another alternative is to have a human pilot the vehicle for part, or all, of the journey, reducing some of the fear associated with self-driving cars’ safety and giving rise to so-called remotely-piloted ground vehicles (RPGVs).

Because this idea needs a stable and constant Internet connection, I wanted to test if the current 4G network is fast enough for these cars to drive and function safely. Relying on a hefty amount of external data about pedestrians, other traffic, road layouts, and more makes things difficult.

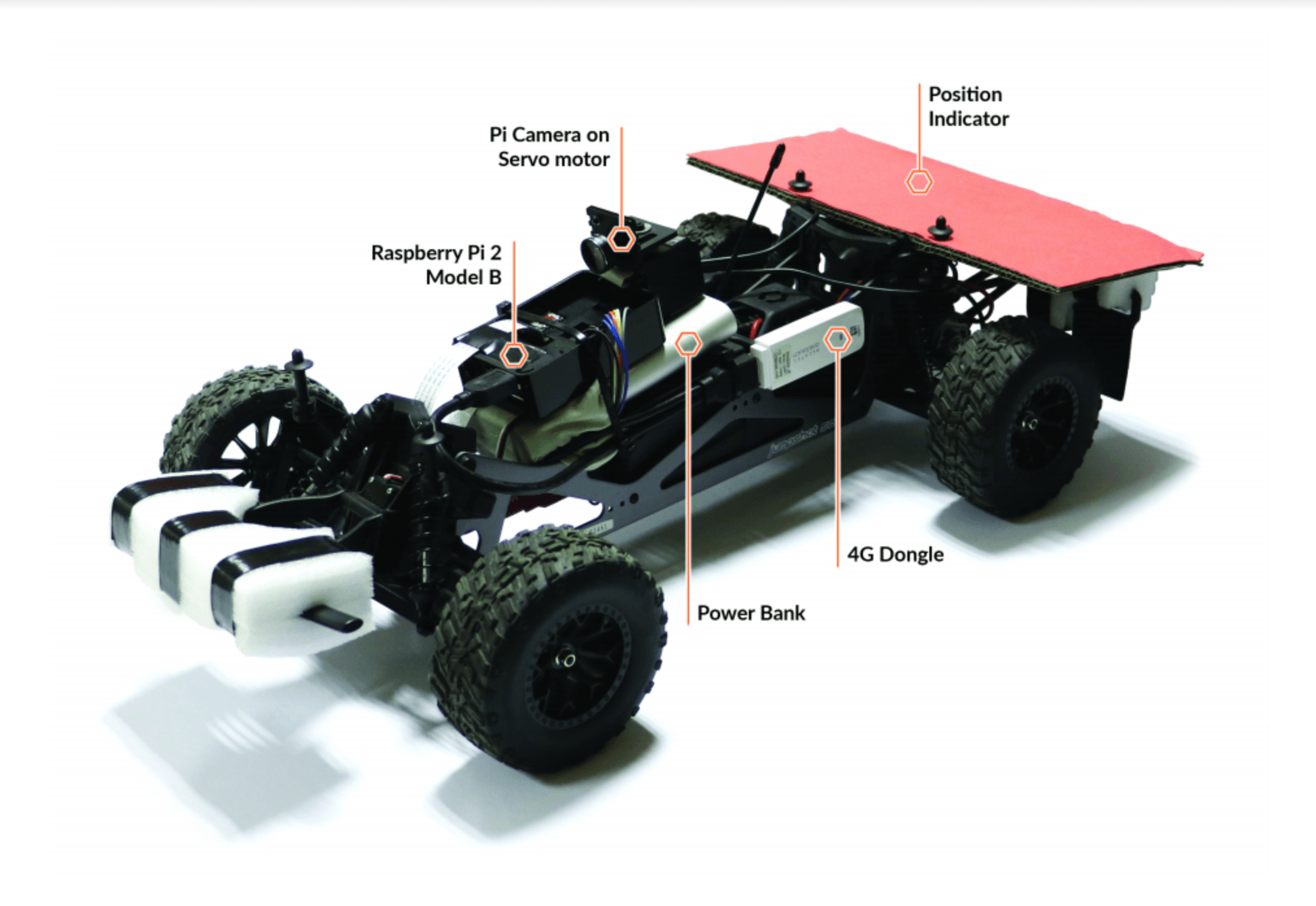

At the Department of Communications and Computer Engineering, (Faculty of ICT, University of Malta [UM]), on a project led by Prof. Ing. Saviour Żammit, we created an RPGV by modifying a radio-controlled vehicle and used it to test the suitability and safety of 3G, 4G, and Wi-Fi networks.

Fast communication between driver and car is crucial for the safety of RPGVs. If information from the car takes too long to reach the driver, they won’t be able to react quickly enough to avoid obstacles and accidents.

On Wi-Fi networks, we found that when the connection moved from one base-station (the receiver-transmitter that serves as the hub of a local wireless network) to another, the handover took too long. This problem meant that whilst the connection was transferring, the video was lost, leaving the car blind. This is obviously dangerous and means that these networks are not safe enough for automated cars. 3G was not fast enough to transmit video in real-time.

The next step was to set up an outdoor racetrack to test the RPGV over the 4G network on UM grounds. We varied the networks’ signal delay and the camera’s range of view, then measured the lap times, distance travelled and road cones hit to calculate driving accuracy. Finally, we compared them to how accurate the drivers thought they were driving.

We concluded that 4G mobile networks allow adequate remote control of an RPGV, although the amount of delay left little room for error. A faster 5G network would be able to act quickly enough to avoid accidents, so self-driving cars will need to wait a bit longer before becoming a reality.

This research was carried out as part of the Masters of Science (Telecommunications) program, Faculty of ICT, UM, supported by GO plc and the Research Fund Committee of the UM.

Author: Clint Galea

Drawing with our eyes

Drawing can be defined as the active exploration of an individual’s mental imagery. John Berger described it as ‘an autobiographical record of one’s discovery of an event—seen, remembered, or imagined.’

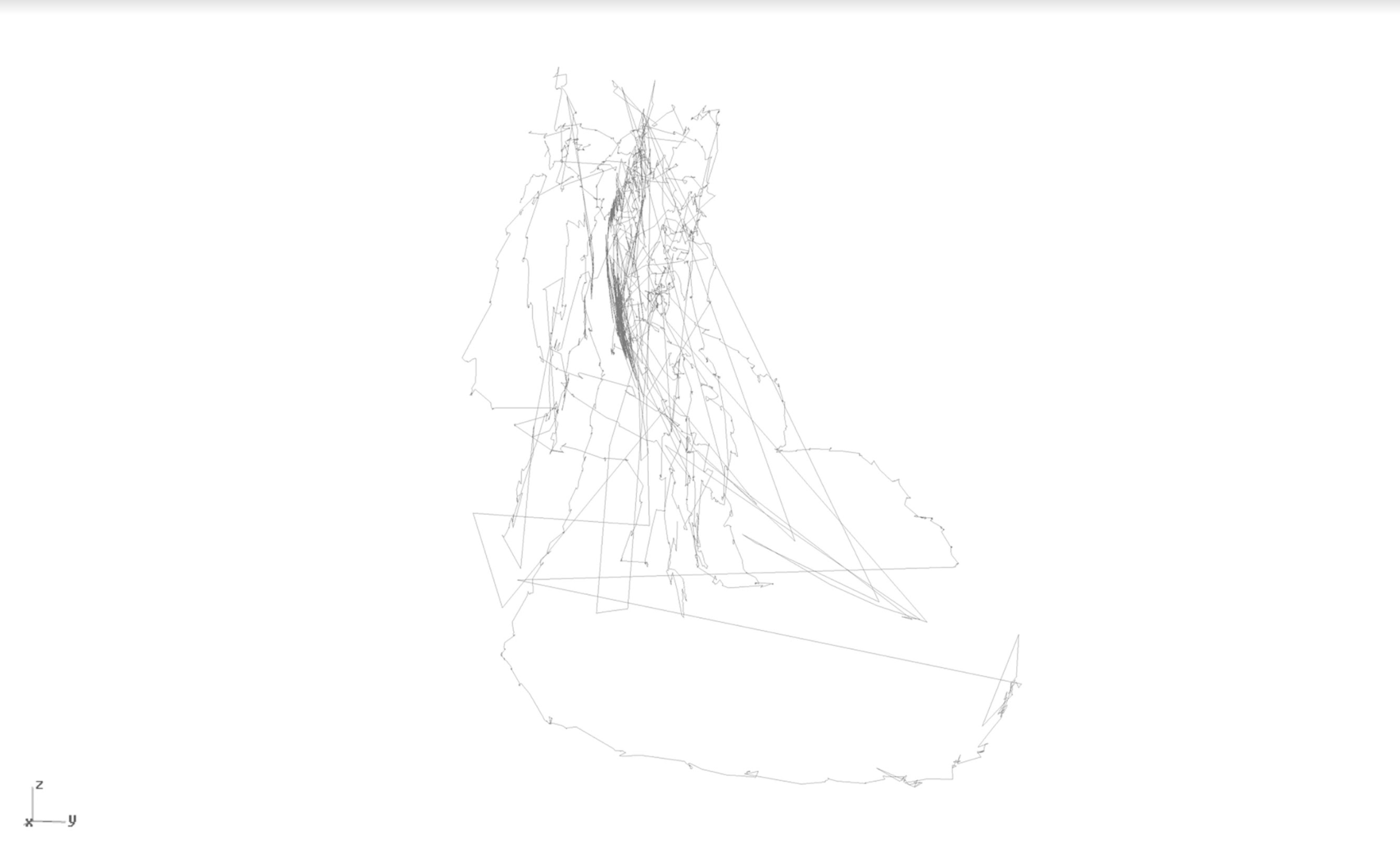

The initial hunch for my research revolved around the idea of drawing with one’s eyes instead of hands by using an eye-tracker.

The approach intrigued me for three reasons. It allowed me to explore the notion that an artist’s skills are in his tools—his hands. The eye-tracker-based technique ‘levelled the playing field’ between artist and non-practitioner by removing hands from the equation. Secondly, through eye-drawing practice, I could also notice a shift in the drawing methods used. Normal drawing involves hand-eye coordination and a degree of intuitive eye movements. In ‘eye-drawing’, these movements have to be suppressed into following contours along the observed worldview, while also restraining the impulse to refer to the accustomed curvilinear hand motions. All this feeds into the fact that eye-drawing cannot be regarded through the same approach as ‘normal’ drawing. Eye-drawn objects have a direct representation tied to their place and time of execution and acquire a technological aesthetic.

I explored these concepts in several experiments. I ran communal ‘life’ eye-drawing classes with first year students reading for an MFA (Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta [UM]). Their resulting visuals were surprisingly individualistic, highlighting their characters, a quality I observed to be constant throughout all eye-drawings.

Using an eye-tracker to draw led to some exciting possibilities. I tested a preliminary algorithm, developed by my colleague Neil Mizzi, (Faculty of ICT, UM) that ‘corrected’ an eye-drawing by comparing it to a real-world picture. The technique could be applied in future eye-drawing devices designed to help physically impaired individuals to draw from real-world images using just their eyes.

It can be argued that art is a subjective experience, both in its creation and perception. Eye-drawing can exploit this subjectivity revealing ‘signature’ gestures through a new way of looking.

This research was carried out as part of a Masters by research at the Department of Digital Arts, Faculty of Media and Knowledge Sciences, University of Malta (UM).

Author: Matthew Attard

Usability – the frustrated user

Today we can say ‘there is an app for everything.’ Android and iOS boast over 3.5 million and 2.2 million apps on their platforms respectively, each of them fulfilling a role, be it social, utilities, entertainment, gaming, productivity, commerce, and much more.

As users continuously feed personal and work-related information into their smartphones, from calendar entries to sign-ins at favourite restaurants, apps are becoming more personalised, learning more about their behaviour.

So what role does usability play in the digital world? The term usability is part of a broader term referred to as ‘user experience’. Usability assesses how easy it is for people to use interfaces. Developers are expected to create apps that people need, but they need to keep in mind that if that app is difficult to manoeuvre, their target audience will stop using it. From users’ perspective, too many apps these days are failing to add enough value, seeing adoption drop off quickly.

At the workplace, employees are expected to learn and use software applications. A lot of these are now available through mobile devices that need to be connected. However, studies conducted in different scenarios such as airport environments and healthcare show that people are struggling to adopt technology.

However, studies conducted in different scenarios such as airport environments and healthcare show that people are struggling to adopt technology.

Most people access apps related to public services on their smartphones and tablets so that they can submit e-forms and conduct work of that sort. Unlike with leisure apps and games, the choice in this field is limited to the apps provided by the public entities themselves. As a result, users or employees of companies become frustrated when apps are not designed effectively.

More usability experts are needed to improve the way apps are designed. Well-designed apps empower people, seeing them become more confident with technology they are unfamiliar with. Better apps contribute to addressing challenges people face when they can’t keep up with the swift advances of the digital world. The use of digital tools that are easy to learn and easy to remember allow users to create, understand, and communicate while continually developing their digital skills. Usability not only boosts digital literacy, it also bridges the gap between tech-savvy users and those we risk leaving behind.

Further reading:

C. Attard, G. Mountain, and D. Maria Romano; ‘Problem solving, confidence and frustration when carrying out familiar tasks on non-familiar mobile devices‘

Author: Dr Conrad Attard

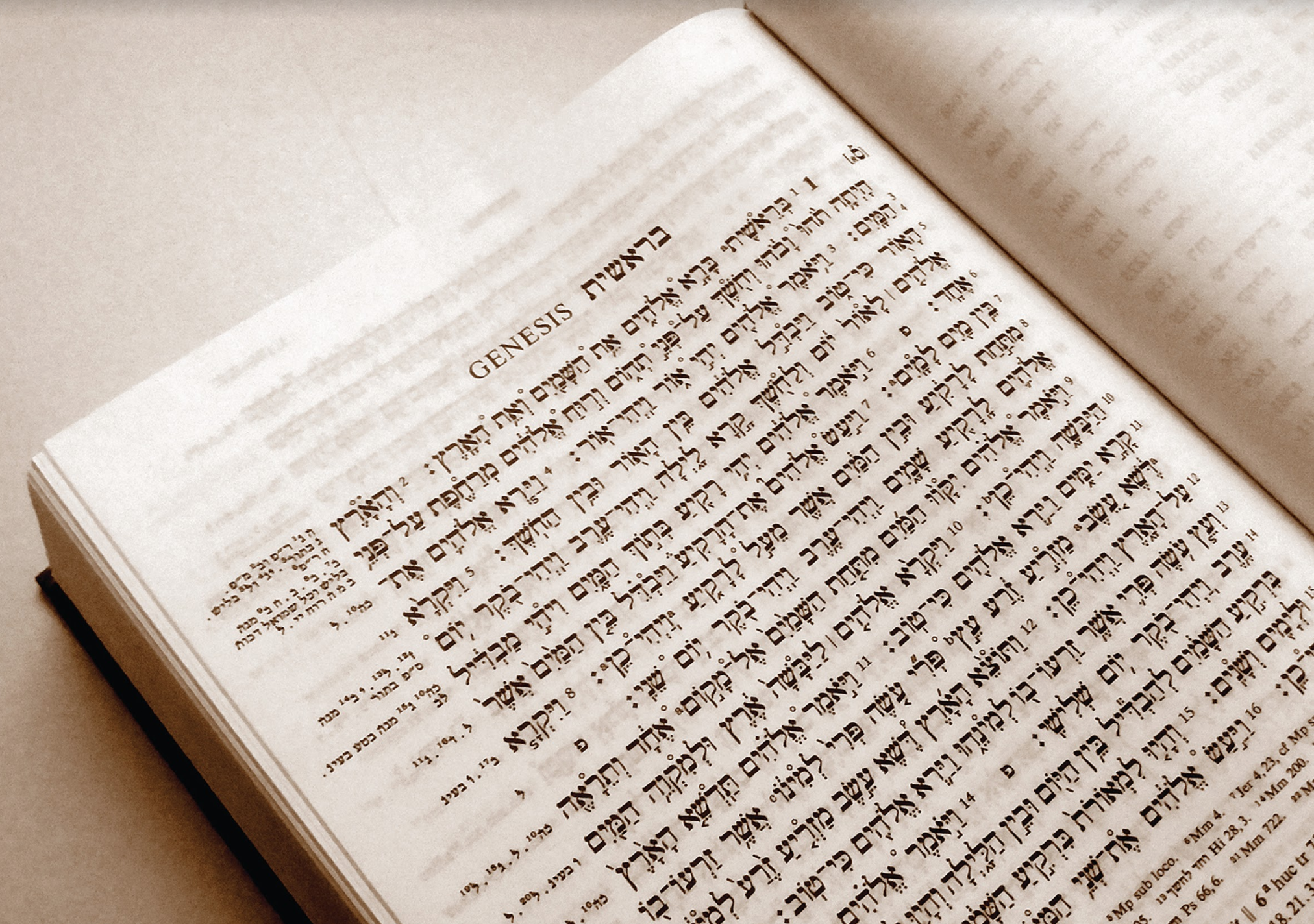

Classical Hebrew undying

Classical Hebrew is the Hebrew of the Tanakh, the Jewish Scriptures, the very source of the Christian Old Testament. Its first appearance in the historical record dates back to the 10th century BCE, and like the other semitic languages from which it emerged, it was written from right to left and comprises only consonants. By the turn of the Common or Current Era, its use as a spoken language was quickly being superseded by Aramaic and Greek. A few centuries later it was a linguistic relic, its use limited to liturgical and literary contexts, not so different from the use of Latin much later in the Christian west.

‘Dead’ languages bring up the question of relevance. They are limited in their vocabulary, especially when compared to their contemporaries; the Classical Hebrew lexicon amounts to just about 10,000 words. Today, they could not be used for communication, on official documents, or for most conventional things. However, there is one function ancient languages fulfill in a far superior manner—interpreting ancient texts.

Modern translations cannot quite capture the nuance of ancient texts. Translators can only convey ideas after making countless choices in the understanding and rendering of words, all while being consciously or unconsciously guided by their own ideological leanings. Translations are essentially interpretative exercises. Armed with knowledge of the original language, a reader can identify the original authors’ ideology, emphasis, word order, and tone. All of these features could easily be lost in translation. For example, should the word ‘meshihu’ in Psalm 2:2 be translated as ‘his Messiah’ or ‘his Christ’ or ‘his Anointed One’? A choice needs to be made, and that choice does make a difference.

Archaeologists use the same concept when studying ancient artefacts, as do epigraphists, the specialists who study inscriptions. Understanding the inscribed language on items leads to a clearer, more colourful picture of its context and origins. The Malta Government Scholarship Scheme supported me in carrying out such an epigraphic study for my doctoral research at the University of Oxford. My project dealt specifically with a group of inscribed pottery sherds discovered at Lachish (modern Tell ed-Duweir) in Israel. Combined with an archaeological and contextual reassessment, these inscriptions provided valuable insight into the socio-political history of early 6th-century BCE Judah, including scribal culture and the mastery of the contemporary Hebrew language, as well as military operations and prophetic activity, all of which strike similarities with the Book of Jeremiah.

Studying Classical Hebrew can be a rigorous mental workout that instills an appreciation for detail: an insight useful across innumerable fields. Not only does it provide a solid foundation for Modern Hebrew, but it offers a fresh perspective for those wishing to read biblical texts in a critical manner. After all, the Bible remains an iconic cultural artefact in the western world, vital when discussing not only ideology but even cinema, literature, music, and art.

Ancient languages give a voice to our history and the people who shaped it, all the while providing food for thought for those in the present.

For more information: The Department of Oriental Studies (Faculty of Arts, University of Malta) offers study-units on Classical Hebrew grammar, syntax, and readings at undergraduate level.