ChatGPT has taken the world by storm since its launch in November 2022. It is a chatbot developed by OpenAI and built on the GPT-3 language model. What sets it apart from other AI chatbots is the sheer amount of data it has been trained on, allowing the quality of its responses to cause waves, leading to headlines such as ChatGPT passing key professional exams. It has also consequently caused concern in academia that it may be used to cheat at exams and assignments. We speak to two academics from the University of Malta, Dr Claudia Borg and Dr Konstantinos Makantasis, to see how academia should adapt. Are such advances a threat to be curbed or an opportunity to be exploited?

Continue readingHow Smart Insoles Can Save Feet of People Living with Diabetes

In Malta, around 10% of the local population is affected by diabetes. This is especially alarming considering that diabetes can affect the blood and nervous system and eventually even lead to foot amputations. Researchers from the University of Malta (UM) and Mater Dei Hospital are trying to address this problem in their project Sit_Diab: Smart Insole Technology for the Diabetic Foot. They developed a novel method of detecting foot complications early enough to take action in time to help save limbs.

Continue readingThe Magic Behind the Screen

THINK talks with director and writer Sarah Zammit on her short film Darb’oħra, and its journey from script to screen

Continue readingCovid and the Elderly

Elderly people in residential care homes have been particularly affected by the pandemic and the safety measures associated with it. Isolation, loneliness, and the lack of physical touch are a few factors that have impacted their mental well-being.

Continue readingPeeling Away the Layers of Time

THINK takes a trip to explore research and archaeological work taking place at Borġ in-Nadur, overseen by Heritage Malta, which will see the Neolithic site freed from modern-day debris and accumulated material to show the original prehistoric structure in all its glory.

Continue readingUniversity on the Edge

The Latin phrase alma mater, translated to ‘nourishing mother’, is frequently used to refer to a university. From that, we get the term alumnus, ‘one who is nourished’ when referring to graduates. But the nourishers and the nourished, the staff and the students, are in trouble.

University life can be incredibly stressful for staff and students alike. The staff have to cope with more people meeting the necessary standards to enter university and the different capabilities and needs they bring with them. Students are under constant pressure to get high marks, meet all their assignment deadlines, and attend extra-curricular activities — not to mention the daily struggle to find parking!

These are the typical and surface-level struggles of University of Malta (UM) staff and students. But the reality is that many of them also struggle with things they won’t mention out loud.

With the Covid-19 pandemic, the stresses of commute times and having to spend long hours at the university have decreased, but mental health struggles have seen a sharp rise.

In 2019 it was already reported that in a sample of 13,000 UM students, 36% met the criteria for a mental health disorder. The Covid-19 situation combined with the switch to online learning has no doubt exacerbated these challenges and created new ones. While many have adjusted to these changes, others are trying to come to grips with the new normal and consequently struggle in their mental health.

Anxiety has taken hold of many during the pandemic, making those already prone to worry even more anxious. Many fear contracting the virus and/or passing it on to loved ones, and so they are constantly vigilant and taking precautions. This hyper-alertness can cause exhaustion of the mind and body, as research indicates a strong correlation between mental wellbeing and bodily health. For example, negative mental wellbeing increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease in particular.

For many, the switch to online learning and telework is adding to the already stressful occupation of being a UM staff member or student. Online learning is a poor substitute for a real classroom. The SALT surveys reported that the majority of UM students (around 76%) were generally dissatisfied with the shift to online learning, and 66% experienced symptoms of anxiety related to their studies. This is due to many factors, including the perception of a lack of understanding and communication from staff as well as being burdened with a bigger workload. In addition, many students and staff struggle to work in unsuitable home environments with distractors like noise, construction work, pets, family members, and children shouting. This forces many staff and students to travel around to cafés or other people’s homes to work efficiently.

These combined stressors are making some students lose enthusiasm for their courses. And in return, lecturers also feel demotivated because of the lack of participation from students.

While UM staff go through their own stresses brought about by the pandemic, most of them are in secure employment. On the other hand, most university students are still young and unskilled, and so get odd jobs in the entertainment, commercial, and tourism industries. Many of these jobs have been slashed due to the pandemic. This, in turn, is causing much anxiety among the student population because they wonder if there will be jobs left for them in the coming summers, or even after they graduate.

The uncertainty of the future, coupled with these stressful and sudden changes, can contribute to depression. The loneliness and isolation caused by the near-complete absence of campus life and social events have no doubt exacerbated these depressive effects. In a local study, an alarming 35% of participants, most of them young, felt extremely lonely in 2020 compared to just 2% in 2019. Many new students have never even met their classmates in person.

Fortunately, the University of Malta remains committed to the mental health and success of its staff and students. While many lectures are not being held physically, the university’s doors are still open to provide a quiet and structured work environment for those who need it. Once lockdown ends the Calm Room will be available from Monday to Friday between 9 am and 5 pm to provide a safe, calm space for students to gather their thoughts and relieve anxiety. And finally, the university offers Counselling Services, a dedicated team of psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers who attend to mental health issues that require particular care.

Interested in the topic? Betapsi has focused their March episode of ‘.Virgola’ on the topic of ‘University Mental Health’ where we have interviewed Prof. Andrew Azzopardi, the Dean of the Faculty of Social Wellbeing, regarding this subject. Visit our Facebook page ‘Betapsi Malta’ for further information.

Further Reading

Definition of ALMA MATER. Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 23 March 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alma%20mater.

Raway, L. (2019). Attitudes towards Mental Health and Willingness to Seek Psychological Help: A Quantitative study among University Students. [Published Bachelor of Honours dissertation], University of Malta.

Laura D. Kubzansky, Jeff C. Huffman, Julia K. Boehm, Rosalba Hernandez et al. (2018). Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Health Promotion Series. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 72 (12), 1382-1396. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.042.

Cuschieri, Attard, Bartolo, Attard et al. (2020). Learning, teaching and assessment during the pandemic at the University of Malta. Findings of the SALT Surveys

Bonnici J., Clark M., Azzopardi A. (2020). Fear of COVID-19 and its Impact on Maltese University Students’ Wellbeing and Substance Use. Malta Journal of Health Sciences. doi: 10.14614/FEARCOVID19/7/20

Counselling Services. (n.d.). https://www.um.edu.mt/services/health-wellness/counselling

An oasis of calm for students with autism: KSU launches Calm Room. (2020, November 25). UM Newspoint. https://www.um.edu.mt/newspoint/news/2020/11/calm-room-launched

The pandemic did not ‘undo’ our exhibition

As 35 University of Malta students prepared to showcase their dissertation projects in an exhibition at Junior College, restrictions to stop the spread of COVID-19 turned their plans upside down overnight. Yet the exhibition, titled Ctrl Z, is still taking place, having moved to where people are – online.

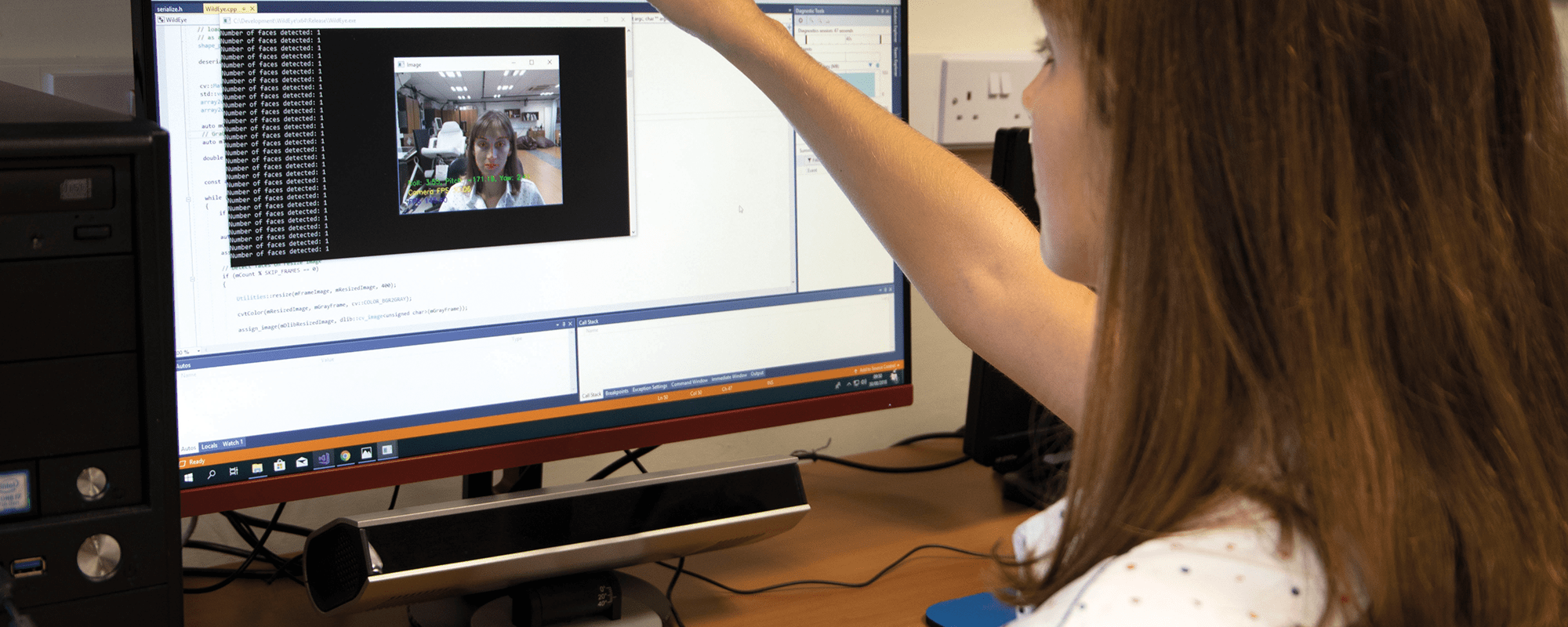

Continue readingEyes front!

How often do your date’s eyes glance down at your chest? Which products do people notice in a supermarket? How long does it take you to read a billboard?

Eye trackers are helping researchers around the world answer questions like these. From analysing user experience to developing a new generation of video games, this technology offers a novel way of interacting with machines. People with disabilities, for example, can use them to control computers. A team at the Department of Systems and Control Engineering (University of Malta) is using a research-grade eye-gaze tracker, worth around €40,000, to test technologies they are planning to commercialise soon.

Continue readingSaving the skates

Author: Gail Sant

They’re called ‘skates’. Yes, like the shoes. Like sting rays, but less popular.

If I had a penny for every time I uttered those words throughout my dissertation years, I’d be a rich woman. You’d think that skates, a regular at the daily fish market, would be part of people’s general fish-knowledge. But it came to me as no surprise, considering how culinarily, environmentally, and economically unappreciated they are.

Continue readingMathematical equation of breast tissue

Author: Daphne Anne Pollacco

Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer in women and the second most common cancer overall. Malta ranked at number 17 among the 25 countries with the highest rates of breast cancer in 2018, according to World Cancer Research Fund International.

Cancer patients often need X-ray imaging for diagnosis and to track recovery. But X-ray radiation is a double-edged sword. It can help to spot the cancer, but it can also contribute to the problem.

Radiation can change the molecular and atomic structure of tissue, potentially leading to other cancers developing. But do any other technologies exist that could achieve the same result without harming patients?

Continue reading