During the run-up to the European Parliament Elections, Prof. Mario Thomas Vassallo grilled two MEP candidates on AGORA, a political talk show broadcast on Campus 103.7. Against the backdrop of numerous elections around the globe, a lack of youth representation, and the rise of the far right, the discussion got us thinking.

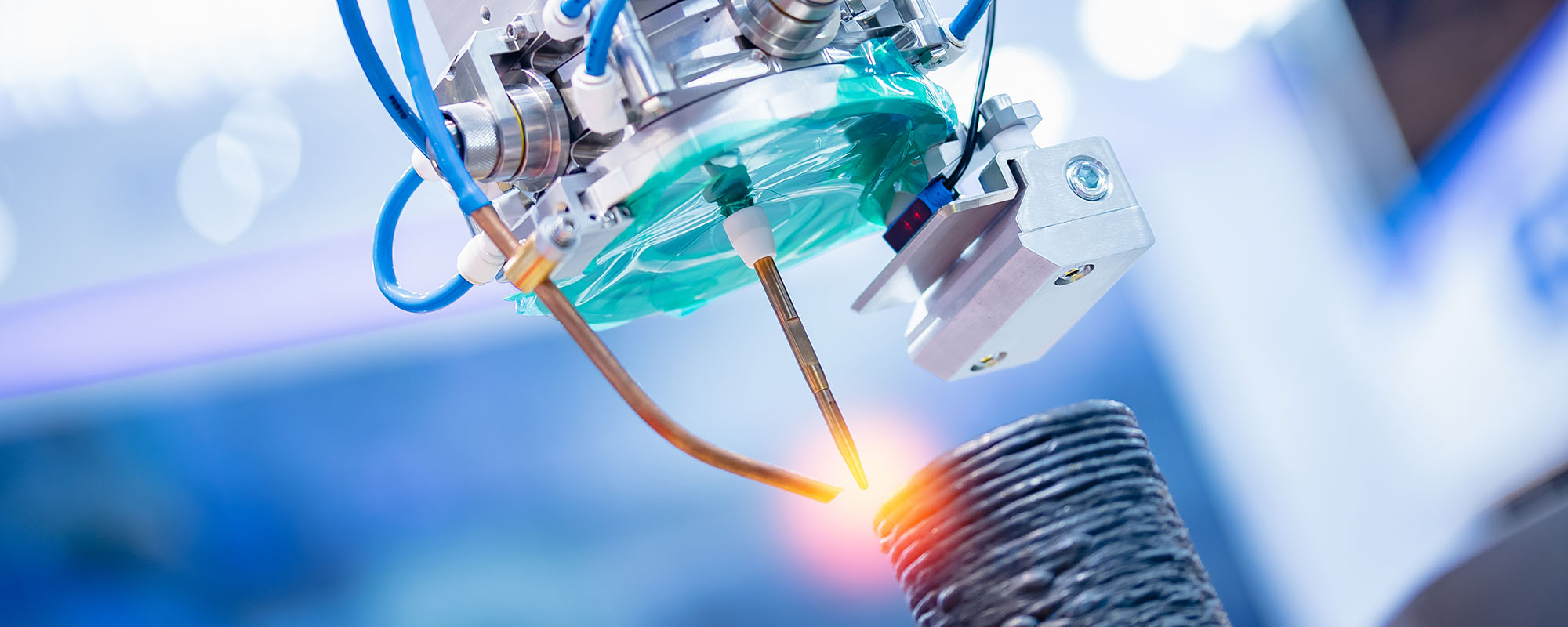

Continue readingSmooth Operator: Improving Surface Finish in Additive Manufacturing

While the advent of 3D metal printing may redefine how designers develop parts for products, the process itself is not without faults. Andre Giordimaina speaks with THINK about the GLAM Project, which aims to improve the process of 3D metal printing by optimising the finish and performance of designed parts.

Continue readingBeyond What Drifts Us Apart

Beyond What Drifts Us Apart is a long-term art project conceptualised and curated by the acclaimed Maltese curator, Elyse Tonna. The 2024 edition took place in and around Gozo’s Dwejra Tower, which proved to be an abundant source of inspiration for this year’s selection of international and interdisciplinary artists. The exhibit was open to the public for a week through a variety of workshops and performances.

Continue readingFinding a Home in Malta

Getting on the property ladder is incredibly difficult. Unless you are fortunate enough that your parents already own several properties, you will most likely be stuck for the rest of your adult life paying off your first (and possibly only) one-bedroom apartment. Is this grim future set in stone, or are there more creative solutions?

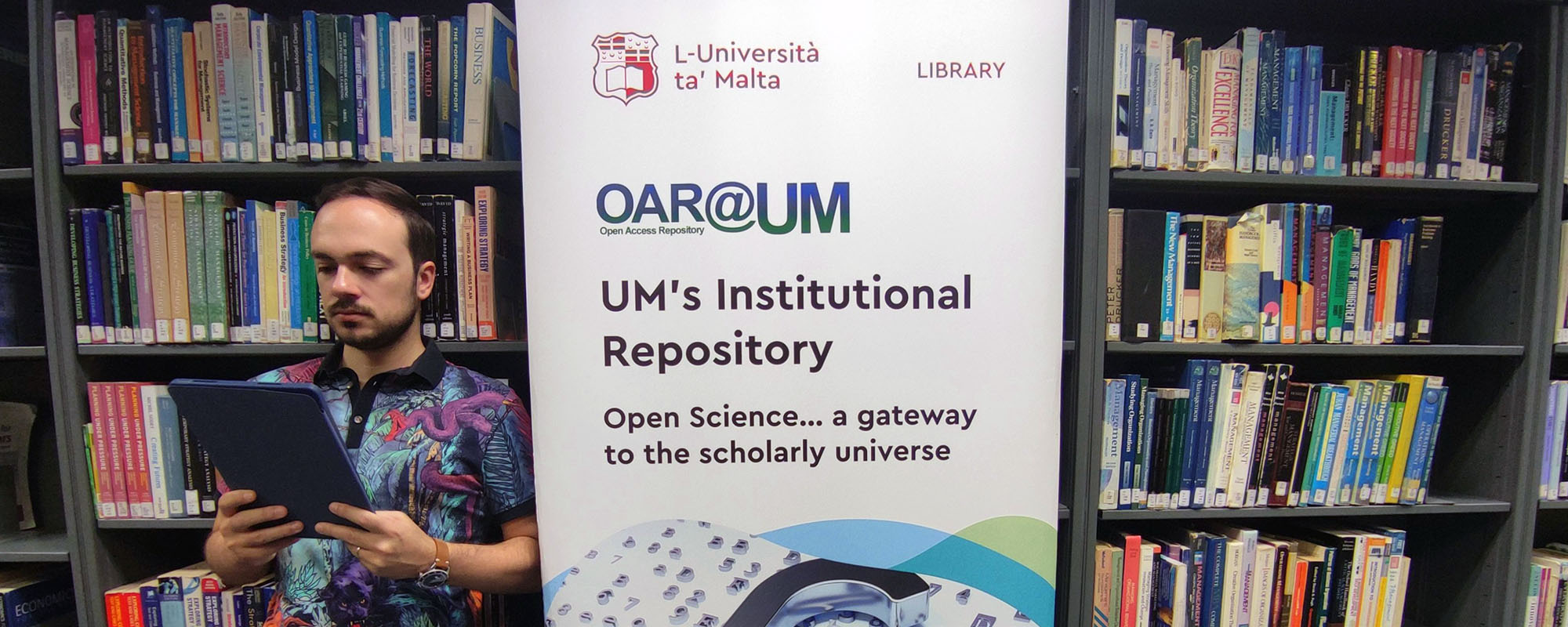

Continue readingA Decade of Open Access at UM

This year marks a significant milestone for UM as we celebrate the 10th anniversary of OAR@UM, the University’s Open Access Repository. Its role reflects UM’s commitment to enhance the visibility and dissemination of research output generated at UM.

Continue reading3D Printing Balloons Inflates Enthusiasm for Future Technology

With the rise in popularity of 3D printing, the medium has become more accessible. What’s more, recent advancements in the field have made the technology rather intriguing. THINK explores the latest UM research on the development of 3D-printed balloons.

Continue readingWhat Happens to Malta’s Private Collections?

Natalie Formosa shares her findings on private artists’ archives in Malta and the nation’s role in preserving such collections.

Continue readingGreen Walls: A Sustainable and Innovative System to Reduce the Impact of Pollution

In cities, pollution remains a pressing environmental concern for pedestrians. THINK sits down with Prof. Ing. Daniel Micallef and Dr Edward Duca from UM, who are using plants and physical barriers to combat traffic-generated pollution.

Continue readingHistory of THINK

How much do you know about the history of THINK? If you’re a THINK superfan, then you know that the first edition wasn’t called THINK. Read on to learn more about how THINK evolved over the last decade.

Continue readingCovid and the Elderly

Elderly people in residential care homes have been particularly affected by the pandemic and the safety measures associated with it. Isolation, loneliness, and the lack of physical touch are a few factors that have impacted their mental well-being.

Continue reading