Card Game Review by David Chircop

Continue readingSensory Apparatus

‘What does it really mean to sense something?’ That was the fundamental question Dr Libby Heaney (quantum physicist and artist) asked herself when she started working on Sensory Apparatus, currently on display at Blitz in Valletta. For almost a year she worked together with Bonamy Devas (artist and photographer) and Anna Ridler (designer working with information and data). For Libby sensing means the collection of data. Science tries to measure everything and is now through so-called ‘big data’ attempting to quantify subjective things, like happiness levels or the perfect online dating match.

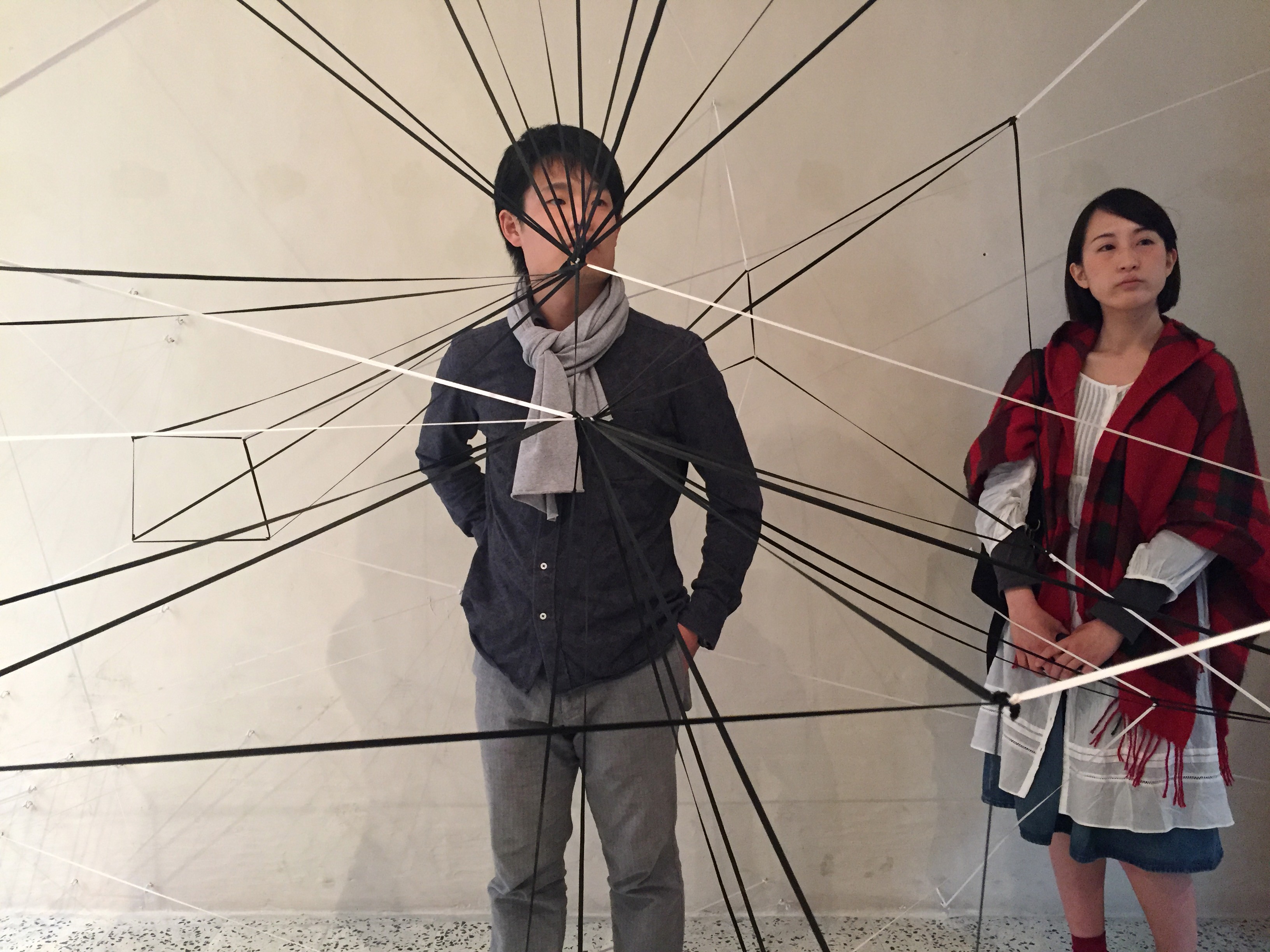

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

Sensory Apparatus visualises the constant surveillance our data is under. In the first room a web of elastic black and white fibres represents a network of light and data. The experience of traversing the space and interacting with the structure is like simultaneously being sensed and sensing the internet. ‘Like the internet, you are missing out if you cannot make it past the first room’, Libby suggests.

The second room has circuit boards and speakers mounted to the walls. People curious enough will trigger a proximity sensor and a computerised voice starts talking. ‘Name. Country. Age. Address.’ What sounds like nonsense at first, quickly develops into the auditive representation of an algorithm. Passing consecutive speakers continuously reveals its different layers. These algorithms are complex programmes, designed to collect the footprints people leave while online. The information is used by marketers to direct and personalise adverts. ‘We wanted to reveal the technology. The actual objects represent the discussion we are trying to make.’

The last room is pitch black. Only when approaching the middle of the room a projector lights up, projecting advertisements directly onto people’s bodies. The commercial pieces, gathered from across Malta, follow every movement, change constantly and are reflected from the room’s glossy walls. At the exhibition opening, once people noticed they were being used as a billboard, they quickly moved away. ‘People change and behave differently in there’, Libby says, making it obvious how advertisements influence us online.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

As a quantum physicist this change in behaviour reminded Libby of the Quantum Zeno effect, a phenomenon where an unstable particle will not decay while it is being observed. For Libby the concept of surveillance and the philosophy behind it led her to Sensory Apparatus. French philosopher Michel Foucault came up with the idea of panopticism, that inspired the exhibition. Panopticism is a social theory extending the panopticon, a prison designed to allow one person to observe all prisoners. Inmates would know they are possibly being observed, but could never be sure. This ultimately changes their behaviour. Sensory Apparatus’ first steps can be relived in the educational room near the artworks. The artists’ personal notes, inspiring articles, and other materials are laid out for everyone to explore.

The free exhibition opens every Tuesday–Thursday from 10am–3pm and Friday–Saturday from 3–7pm at Blitz, 68 St Lucia Street, Valletta, until April 6. For more information see thisisblitz.com

Sensory Apparatus is supported by Arts Council Malta / Malta Arts Fund.

Google’s deepest dreams and nightmares

By Ryan Abela

In Artificial Intelligence, neural networks have always fascinated me. Based on biological concepts similar to human brains, artificial neural networks consist of very simple mathematical functions connected to each other through a set of variable parameters. These networks can solve problems that range from mathematical equations to more abstract concepts such as detecting objects in a photo or recognising someone’s voice.

Float

FLOAT was an interactive exhibition that explored light. The exhibition was launched as a one-off event of lit installations spread over the floors of the Faculty for the Built Environment (University of Malta) on the evening of 3 July 2015. The exhibition had aerial walkways, floating rooms, colour bursts, and cityscapes captured in panes of glass.

INDIE GAMES

How can a video game ask questions about life, art, and frustration? Giuliana Barbaro-Sant met up with Dr Pippin Barr to tell us about his game adaptation of Marina Abramović‘s artwork The Artist is Present.

In each creative act, a personal price is paid. When the project you have been working on so hard falls to pieces because of funding, it is hard to accept its demise. The feeling of failure, betrayal, and loneliness is an easy trap to fall into. This is the independent game maker’s industry: a bloodthirsty world rife with competition, sucking pockets dry from the very beginning of the creative process.

Maltese game makers face a harsher reality. Not all game makers are lucky enough to make it to the finish line, publish, and make good money. Rather, most of them rarely do. Yet, if and when they get there, it is often thanks to the passion and dedication they put into their creation — together with the continuous support of others.

Dr Pippin Barr always had a passion for making things, be it playing with blocks or doodling. His time lecturing at the Center for Computer Game Research at the IT University of Copenhagen, together with his recent team-up with the newly opened Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta, only served to reincarnate another form of this passion: Pippin makes games. At the Museum of Modern Art in New York he exhibited his most well known work: the game rendition of Marina Abramović’s The Artist is Present. He thought of the idea while planning to deliver lectures about how artists invoke emotions through laborious means in their artworks. In The Artist is Present, artist Marina Abramović sits still in front of hundreds of thousands of people and just stares into their eyes for as long as participants desire.

There is more to this performance than meets the eye. Beyond the simplistic façade, Barr saw real depth. Through eye contact, the artist and audience forge a unique connection. All barriers drop, and human emotion flows with a great rawness that games are so ‘awful’ at embodying. Yet, paradoxically, there is a militariness in the preparation behind the performance that games embrace only too well. Not only does the artist have to physically programme herself to withstand over 700 hours’ worth of performing, but the audience also prepares for the experience in their own way, by disciplining themselves as they patiently wait for their turn.

“It’s a pretty lonely road and it can be tough when you’re stuck with yourself”

Pippin Barr

‘Good research is, after all, creative,’ according to Pippin Barr. By combining his academic background with his creative impulse, he made an art game — a marriage between art and video games. These are games about games, which test their values and limits. Barr relishes the very idea of questioning the way things work. His self-reflexive games serve as a platform for him to call into question life’s so-called certainties, in a way that is powerful enough to strike a chord in both himself and the player. He is looking to create a deep emotional resonance, which gives the player a chance to ‘get’ the game through a unique personal experience. Sometimes, players write about his games and capture what Pippin Barr was thinking about, as he put it, ‘better than I could myself’, or read deeper than his own thoughts.

As far as gameplay goes, The Artist is Present is fairly easy to manoeuvre in. The look is fully pixellated yet captures the ambience at the Museum. The first screen of the game places the player in front of its doors and you are only allowed in if you are playing the game during the actual exhibition’s opening hours in America. Until then, there is no option but to wait till around 4:30 pm our time (GMT+1). The frustration continues increasing since after entering you will still have to wait behind a long queue of strangers to experience the performance work. This reflects real world participants who had to wait to experience The Artist is Present. If they were lucky, they sat in front of the artist and gazed at her for as long as they wanted.

Interestingly, Marina Abramović also played the game. She told Barr about how she was kicked out of the queue when she tried to catch a quick lunch in the real world as she was queuing in the digital one. Very unlucky, but the trick is to keep the game tab open. Other than that, good luck!

Despite that little hiccup, Abramović did not give up on the concept of digitalising the experience of her art. After The Artist is Present, Barr and Abramović set forth on a new quest: the making of the Digital Marina Abramović Institute. Released last October, it has proven to be a great challenge for those who cannot help but switch windows to check up on their Facebook notifications – not only are the instructions in a scrolling marquee, but you have to keep pressing the Shift button on your keyboard to prove you are awake and aware of what is happening in the game. It is the same kind of awareness that is expected out of the physical experience of the real-life Institute.

The quirkiness of Barr’s games reflects their creator. Besides The Artist is Present, in Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment, he adapted a Greek Sisyphus myth to experiment with the frustration of not being rewarded. In Mumble Indie Bungle, he toyed with the cultural background of indie game bundles by creating ‘terrible’ versions with ‘misheard titles’ (and so, ‘misheard’ game concepts) of renowned indie games. One of his 2013 projects involves the creation of an iPhone game, called Snek, an adaptation of the good old Nokia 3310 Snake. In his version, Pippin Barr turned the effect of the smooth ‘naturally’ perfect touch interface of the device upon its head, by using the gyroscope feature. Instead, the interaction with the Apple device becomes thoroughly awkward, as the player has to move around very unnaturally because of the requirements of the game.

This dedicated passion for challenging boundaries ultimately drives creators and artists alike to step out of their comfort zone and make things. These things challenge the way society thinks and its value systems. Game making is no exception, especially for independent developers. An artist yearns for the satisfaction that comes with following a creative impulse and succeeding. In Barr’s case, being ‘part of the movement to expand game boundaries and show players (and ourselves) that the possibilities for what might be “allowed” in games is extremely broad.’

Accomplishing so much, against the culture industry’s odds, is a great triumph for most indie developers. For Pippin Barr, the real moment of success is when the game is finished and is being played. Then he knows that someone sat with the game and actually had an experience — maybe even ‘got it’.

Follow Pippin Barr on Twitter: @pippinbarr or on: www.pippinbarr.com

Giuliana Barbaro-Sant is part of the Department of English Master of Arts programme.