Concrete for sustainability

Concrete is the most used building material supporting the construction boom. Hans-Joachim Sonntag talks to Dr Ruben Paul Borg about advances in cement bound materials that can lead towards sustainable development, more durable buildings, and a lower carbon footprint.Continue reading

Bloomin’ roofs go green

Weather in Malta can be extreme. Summer is scorching. Winter brings storms. Some might blame nature and leave it at that, but there are solutions to these problems. Nigel Borg talks to Antoine Gatt about one of them.

History, Medicine, and Art

We still live in a world where being beautiful is vastly important.

Throughout history the concept of ‘beauty’ has been merged with our concept of what is morally ‘good’. Since the Ancient Greeks, who thought that beauty was inherently good and ugliness was inherently evil, we have struggled to move away from this way of thinking. A ‘normal’ individual is usually de ned as ‘beautiful’ in some sense, be it through good health, social class, or appearance. Problems arise when the binary emerges, seeing deviations from the norm rejected as ugly, dirty, immoral, and ‘sick’.

Working with various international research instuitions across Europe and the US, Professor John Chircop (Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Malta) is delving into how our understanding of what is beautiful is used within the social, political, and medical spheres of our society to mould perceptions and construct ways of control over how we see and treat ourselves and others. Our perceptions of what is beautiful or ugly shapes constructions of the ‘Other’, and makes easier the control of sectors of society that are considered to be a threat to public health and the social order—the destitute, prostitutes, and criminals—dirty, diseased, amoral, and ugly. There are striking examples in history of medical institutions isolating those that did not t the norm. To this day, the idea of ‘beauty’ still segregates society.

Historically, disease was thought to be contagious and transmitted through physical contact, or even inhalation. In Europe, even up un l the early 20th century people were encouraged to keep a safe distance between themselves and anyone who might be considered ‘dirty’ and even contagious. Racial discrimination against Arab Muslim pilgrims upon returning from their annual Hajj saw them detained in quarantine for fear they might be carriers of disease from these ‘dirty’ places. Before being granted re-entry to southern Europe, they had to endure physical examination and fumigation to cleanse them. While this selective segregation based on ethnicity may seem ridiculous now, are things really so different today?

Chircop suggests not. ‘These same concepts are shown today by the way we treat migrants from war-torn countries.’ In general, non-European and, especially, irregular migrants are segregated, kept away from society, and treated as second-class citizens. In place of quarantine ‘fumigation’, we now use biometrics, with routine physical tests, and vaccination. We can try and justify this by highlighting the developments in technology, justifying our actions by emphasising the scientific or ‘medical’ benefit of these examinations. But really the ideas behind this are the same; by treating a population as different, necessary for testing, we automatically create a distinct on between ‘us’ and ‘them’. This segregation is then reinforced in art, political cartoons, popular films, television, and wider social media.

Although much progress has been made in human rights and fair treatment of individuals, prejudice is insidious and subtle. It has melded itself into the fabric of society, and we need to be aware of it to change it. Chircop states, ‘to go about changing this, we must start from the present, and go back in history.’ By learning from our past, we can expand the concept of beautiful in today’s society.

Malta Seismic Network

| Tech Specs |

Sensors: Trillium 120PA/Trillium Compact Technology : 3 symmetric triaxial sensors with force feedback Bandwidth: 8mHz to 150Hz Weight: 7.2kg/1.2kg Height: 20cm/10cm Power consumption: 600mW/160mW Data Loggers: Centaur 24-bit ADC, Internet-enabled |

The earth’s surface is never still. And that is why over the past three years the Seismic Monitoring and Research Group (Faculty of Science, Department of Geosciences), has been placing its ears more firmly to the ground, listening to the smallest vibrations of our Earth.

Since 1995 the Malta Seismic Network has grown from a single seismic station at Wied Dalam to a network of six broadband instruments all over the Maltese Islands.

Stations are installed in several locations. The sensitivity of the instruments means that they need to be homed in places where human interference is minimal. Church crypts and underground tunnels are perfect. Being broadband instruments, they can detect very slow vibrations from frequencies less than a millihertz (the whole Earth’s normal mode frequencies), to tens of hertz (ground motion from anthropogenic noise and near earthquakes).

The network can record close ‘microearthquakes’ with equal clarity to large earthquakes from all over the globe. These massive quakes send seismic waves travelling through the planet’s interior at several kilometres per second. All of this data is transmitted to a University of Malta server, which distributes the information to data centres worldwide.

But what is the advantage of having so many stations in such a small area? Firstly, researchers can gather valuable information and share it with the seismological community to build more detailed models of the Earth’s interior. Secondly, an immediate advantage is the enhanced detection and analysis of smaller and smaller earthquakes from all sides of the island, leading to a deeper insight of active faults. Thirdly, the network gives precious information on the proper es and structure of the rocks of Malta. More accurate information about our islands’ composition and behaviour will help make Malta earthquake-ready.

Where has ‘woman’ gone?

Back in the old days it was assumed by most that if you had male sexual characteristics you were a MAN and as such your nature was to be macho, brave, and aggressive and bring in the money for the family; and of course, if you had female sexual characteristics, you were a WOMAN, and as such your nature was to be sensitive, emotional, nurturing, and an ‘angel’ in the home.

Then we discovered ‘gender’, i.e. not the physical/biological characteristics, but the social and cultural meanings attached to being a woman or a man, our learnt behaviour. At this stage, it became clear that having male sexual characteristics in itself did not necessarily make one incapable of holding a baby or wiping up vomit. At the same time, it was now agreed that possessing female sexual characteristics did not necessarily make one unfit for public life, employment outside the home, or leadership (political or otherwise).

And we embraced these changes with gusto! Now, we thought, women (and men, or other) could be whatever they wished to be! We were no longer held back by our sexual characteristics, by being seen as ‘woman’ (or ‘man’). This was a big step forward for ‘gender’ equality.

Somewhere along the line however, ‘woman’ disappeared…

In the past, we spoke about women’s liberation, women’s rights, feminism, equality for women, women’s studies, violence against women. When we talked about domestic violence, what we meant was intimate partner violence perpetrated far more by men against women.

Nowadays we speak about human rights, gender equality, gender studies, gender-based violence, family violence, and when we speak about domestic violence we get told; ‘What about the men? What about the children? What about older adults?’ When we speak about feminism, we are labelled passé or extremists.

Effectively, ‘woman’ has become invisible. The still-dominant patriarchal discourse has succeeded, with the help of all of us, in neutralising ‘woman’ and camouflaging this as ‘progress’.

If we had indeed achieved ‘gender equality’, if women’s rights as human rights were really being upheld, if we had eliminated violence against women, then this would be right and proper… But have we?

My answer to that is, of course, as you would expect, a resounding NO, we have not! And making ‘woman’ invisible once more will not help us achieve this!

Photo by Steven Levi Vella from Artemisia: 100 Remarkable Women, a project by Network of Young Women Leaders

Nurturing language development through interaction

Language is at the core of what makes us human. From birth, we interact through language, making our way through gurgling and babbling to words, and, eventually, telling (tall) stories. It is important to nurture this linguistic development as early as possible, and in Malta, this involves exposure and sensitivity to the forms and dialects of at least two languages: Maltese and English.

Such growth can be nurtured by setting a good example so that children have a solid language basis to build upon. Here, it all boils down to one key point: interaction. Language is a two-way process, so for a child to truly benefit, they need to interact with others from birth—TV cartoons just do not cut it.

At the earliest stages, language is all about sounds and bonds, not about learning letters or reciting a poem. However, even then a child sensitive to differences and variation in language. Children know that home language is different from what they hear outside in the wider community. For Maltese children, it is useless to place early focus on lamenting the distinction between ‘Trid ice cream?’ instead of ‘Trid ġelat?’ as both are equally well understood in Malta. What is more important is that a child has enough exposure to become sensitive to which version or dialect to use in which context. In English, we have no problem singing the nursery rhyme ‘Horsey, horsey don’t you stop…’ despite knowing that the established word is of course ‘horse’ because experience shows us that children happily grow out of their ‘baby’ language. The same is true of the different forms of languages and dialects typical in a multilingual society. As we grow older, we can become sensitive to which forms of a dialect or language are best understood in the home, amongst friends, or at work.

Apart from parents, children spend most of their me in school. If schooling is meant to be about encouraging children to reach their full potential, then this should also hold true linguistically. Just as a sporty or musical child is identified and encouraged to work on their natural talent, a child whose linguistic skill is recognisable should get the same treatment. That talent should be nurtured—they might be the country’s best lawyer in a few years’ time.

Equally, it is important to leave no child behind. A truly holistic education recognises that physical activity is vital, perhaps even more so, for the less sporty child. The same applies in languages. We must ensure that every child has the opportunity to express themselves both in speech and writing, even if they seem to struggle. After all, we don’t teach an unsteady runner how to run by making them sit and watch while we run a race for them. Similarly, children learn how to speak and write by practising the languages, not listening to (lengthy) explanations about how to use a language.

This is what nurturing skills is all about. If we want to raise con dent, knowledgeable youngsters, we must allow them to constantly practise ways to get their message across. In Malta’s rich linguistic environment, this means nurturing all our dialects and forms of language in whatever shape or form available to us. It is only through this process that we can then shape rich, meaningful forms of communication amongst ourselves, and the wider world.

Do you think this is a game?

Picture an item of furniture. Was it a table, a chair, or a wardrobe? Our ideas of furniture are not oriented around what it does, or even its essential nature, but rather around all the common examples we see around us and the cognitive web of interrelations that builds in our head.

This fictional furniture is just an analogy. Supervised by Prof. Gordon Calleja, I investigated how language affects our preconceptions of what games are and what they should do. Our ideas about games are not related to their potential or their openness but to constructions in our mind.

My research was mostly within the philosophy of language. I explored how our ideas of what a thing is are not grounded in what it does or is, but around a cognitive image, created by what we often see and label it as.

My research was mostly theoretical. It showed how other game researchers might have been misguided or had counter-intuitive results. Their research tried to define what games are and did not realise that this went against how we used the word ‘games’, i.e. as a container for all the things we collectively consider game-like.

That said, I also had the opportunity to test-drive this work in a game I am currently developing with Dr Stefano Gualeni, which analyses what the word soup means.

Apart from answering the long-standing question of what a game actually is, this research also shows how games would benefit from being more inclusive and experimental. By creating these types of games, we can attract people whose cognitive model of a game is different from the norm. Similarly, by designing games that are more open, we can stretch the web of interconnections in people’s minds, potentially showing how games are more akin to life than we realise.

Are you ready to play?

This research was carried out as part of the Masters in Digital Games, carried out by the Institute of Digital Games at the University of Malta.

Striving for Scientific Excellence

Research is a complex endeavour. From funding, to project management, quality assurance, and so much more, any active project, whether for applied or fundamental research, needs to tick a whole list of boxes for it to achieve its full potential. This is where we, the Research Support Services Directorate (RSSD), come in.

Our goal is to provide researchers with comprehensive support towards achieving scientific excellence, from identifying and advising on funding opportunities to getting specific accreditation of their scientific methods. And our newly established directorate reflects the growing ambition of the University of Malta (UM) to develop into a world-class research institution. We are a team of nine enthusiastic individuals with very diverse backgrounds.

Having worked and studied (apart from the UM) in institutes such as the University of Cambridge, Max Planck Institute, Imperial College London, University College London, University of Nottingham, the European Institutions, as well as the private companies like GlaxoSmithKline, Teva (Actavis), Novartis and Methode Electronics, our team is excited to bring international and private sector experience to the UM.

How can RSSD help you?

The most attractive funding opportunities for scientists at the UM nowadays are based on competitive European Union instruments. Preparation for them is intense, and only the most innovative and ground breaking ideas hit the mark. Our team can guide you not only to identify the most suitable funding opportunity, but also on building the right team, all the while ensuring that strict EU guidelines are being followed. We also help you identify and approach collaborators in Academia, private industry, and the state—a requisite of many EU funding programmes. To this end, RSSD aims to be the interface between the academics, researchers, and the general administration, as a one-stop shop for research funding. Once the project is successful and funded, we will then link it with the range of support services available. But that is not where our contribution ends.

On the laboratory and infrastructural side of RSSD, we help the scientific, technical, and laboratory staff at the UM to bring experimental laboratories to a world class level. The multifaceted nature of this work makes it difficult to summarise. Among other things, it involves building services, laboratory output, systems design and commissioning, followed by quality assurance, such as managing standard operating procedures (SOPs) and supporting and writing equipment tenders, creating and managing asset databases, and ensuring proper waste management. We can also contribute to managing your projects, all in the bid to improve the efficiency, productivity, and function of any laboratory.

The next step in this chain of quality assurance is obtaining accreditation for some of the techniques and methods used. To this end, accreditation and SOPs ensure reliable, repeatable, and reproducible measurements, a must for work in and with the private sector.

RSSD will give you the right support needed to achieve your vision.

How to get in touch?

We are based on the first floor in the Regional Building, Triq l-Imħallef Paolo Debono, or simply drop us an email on rssd@um.edu.mt or visit our website at um.edu.mt/rssd

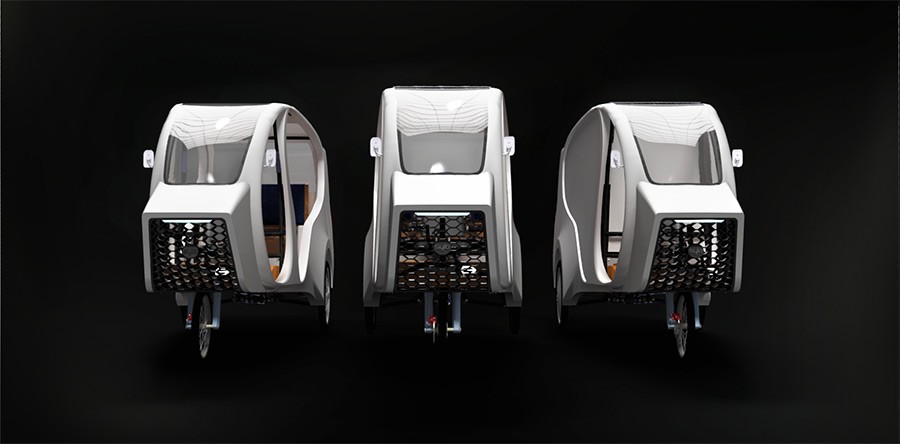

Sylo

Function, form, safety, and environment. SYLO is a family of hybrid cycle rickshaws that fulfils all four design pillars to deliver good performance and a smooth ride. SYLO is designed for short distances, catering to commuters and delivery services. What sets it apart from its counterparts is its mixed-propulsion technology, using both photovoltaic panels and pedal power. Adding to its ‘green’ points is the fact that recyclable plastics have been used for the body. This helped from an engineering perspective because it kept the vehicle light, allowing it to serve its function despite the difficult terrain it must operate in.

What sets it apart from its counterparts is its mixed-propulsion technology, using both photovoltaic panels and pedal power.

Form was an especially important factor in the design process. As the aim was to use this vehicle both within the historical context of the capital city, Valleta, and in cosmopolitan spaces such as Paceville and Bugibba, it was essential for the vehicle to complement its built environment, be it classical or contemporary. Towards this end, bold lines were used, making the vehicle look distinct without looking alien.