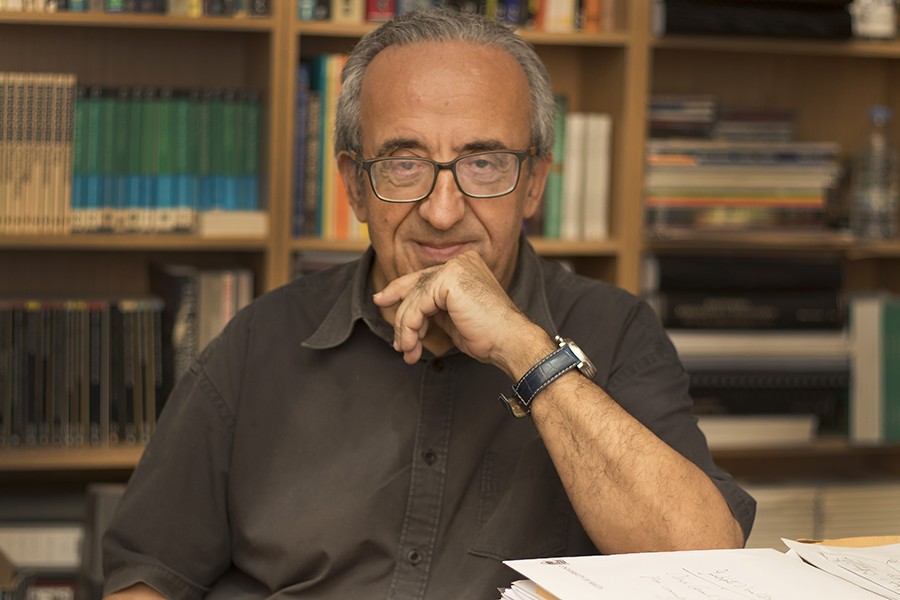

In this age of specialisation, finding a niche is key to most people’s career progression. But it is not the only way. Cassi Camilleri sits down with philosopher poet Prof. Joe Friggieri to gain insight into his creative process.

It was a very warm April day when I found myself sitting in front of Prof. Joe Friggieri. My heart was racing—I had just run up three flights of stairs for a rescheduled meeting after having missed our first earlier in the day. I had lost track of time while distributing magazines around campus. My eyes briefly scanned his library, wishing it was mine, then got right down to the business of asking questions.

Friggieri balances between two worlds: the academic and the creative. His series Nisġa tal-Ħsieb, the first history of philosophy in Maltese, is compulsory reading for philosophy students around the island. His collections of poetry and short stories have seen him win the National Literary Prize three times. I ask Friggieri if he separates his worlds in some way. ‘I can’t stop being a philosopher when I’m writing a short story or play. Readers and critics of my work have pointed that out in their reactions,’ he says. ‘I do not necessarily set out to make a philosophical point in my output as a poet, short-story writer, or playwright, but that kind of work can still raise philosophical issues.’

‘Dealing with matters of great human interest—such as love or the lack of it, happiness, joy and sorrow, the fragility of human relations, otherness, and so on—in a language that is markedly different from the one used in the philosophical analysis of such topics can still contribute to that analysis by creating or imagining situations that are close to the experiences of real human beings,’ Friggieri illustrates.

The urge to write

In reality, Friggieri is usually inspired by day-to-day moments, things normally overlooked in today’s loud and busy world. ‘In my literary works, I am inspired by what I see, hear, and feel; by people and events, by what I read about and by what I can remember,’ he says. It could be anything from a news item to a painting, a whiff of cigarette smoke, a piece of music, or a word overheard at a party. ‘All of that can trigger off an idea. Then, when I’m alone, I seek to elaborate the thought and to convey it to others by means of an image or series of images in a poem, or as part of the plot in a short story or play.’

While on the subject of inspiration and starting points, I wondered: how does Friggieri work? First, he swiftly explains his aversion to using computers for his writing. ‘I do all my writing the old-fashioned way,’ he notes. ‘I use pen and paper. I find it much easier to write that way than on my computer. It feels like my thoughts are taking shape literally as I push my pen from left to right across the page. I think with my pen, much in the same way that a concert pianist thinks with her fingers and a painter with her brush. It’s that kind of feeling that makes me want to go on writing.’ At this point, the subject of the Muse comes up. Is this something Friggieri believes in? ‘Waiting for the Muse to inspire you is just a poetic way of saying you need to have something to write about and you’re looking to find the right way of expressing it,’ Friggieri explains. ‘I write when I feel the urge or the need to write,’ he tells me with a smile.

The sheer volume of work Friggieri has built up over the years seems to imply that he writes daily. But in reality, his workflow is more akin to sprints than a marathon. He tells me deadlines are a good motivator for him to write, providing a tangible goal he can work towards. ‘My first two collections of short stories were commissioned as weekly contributions to local newspapers,’ Friggieri says. ‘That’s how ‘Ir-Ronnie’ was born.’ Ir-Ronnie is a man who finds himself overwhelmed by life’s pressures: family, work and everything in between. As he starts to lose touch with reality, ‘ordinary, everyday living becomes an ordeal for him, an obstacle race, a struggle for survival,’ says Friggieri. More recent works, such as his latest collections of short stories—Nismagħhom jgħidu and Il-Gżira l-Bajda u Stejjer oħra—also reflect this realism, exploring the complexity of interpersonal relations between different people from different walks of life. On the other hand, Ħrejjef għal Żmienna (Tales for Our Times) finds its roots in magical realism, which makes these stories a very different experience for his readers. The books have been well received, with translations into English, French, and German. Paul Xuereb, who worked on the English translation, described the tales as ‘drawing on the dream-world and waking reveries to suggest the ambiguity and often vaguely perceived reality of our lives.’

The Creative Philosopher

When it comes to talking about his other works and creativity, Friggieri often refers to language. When I asked him about his thoughts on creativity and whether he believed everyone to be ‘creative’, his response was positive. ‘As human beings, we are all, up to a point and in some way, creative,’ he says. A prime example is humanity’s use of language. ‘Think of the way we use language. Dictionaries normally tell you how many words they contain, but there’s no way you can count the number of sentences you can produce with those words. Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules. In a very real sense, every individual uses language creatively, in a way that is very much his or her own. I think the best way to understand what creativity is all about is to start from this very simple fact.’

Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules.

Is Friggieri creative when he writes his philosophical papers? ‘Yes,’ he nods. ‘Each kind of writing has its own characteristic features. But creativity is involved in all of them.’ With philosophy, ‘you need more time,’ he notes. ‘You need to know what others have said about the subject, so it involves researching the topic before you get down to saying what you think about it. When it comes to writing a poem or play, you’re much freer to say what you like, much less constrained.’

In fact, Friggieri has five plays under his belt. Here is where the two worlds of academia and creative writing merge. ‘In three of my five full-length plays, I make use of historical characters (Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Socrates) to highlight a number of issues in ethics and aesthetics that are still very much alive today,’ says Friggieri. Taking L-Għanja taċ-Ċinju (Swansong) as an example, Friggieri explains how ‘Socrates defends himself against his accusers by raising the same kind of moral issues one finds in Plato’s Apology. The Michelangelo and Caravaggio plays, on the other hand, highlight important questions in aesthetics, such as the value of art, the relation between art and society, the presence of the artist in the work, the difference between good and bad art, and the mark of genius.’

Talking of theatre, Friggieri remembers how, before writing his first play, he had directed several performances. This was where he learnt the trade and what it meant to have a good production. ‘I have also had the good fortune of working with a group of dedicated actors from whom I learnt a lot. In my view, one should spend some time working in theatre before starting to write for it.’

As time was pressing, and the sun was starting to move away from its opportune place in the window, I asked Friggieri one last question, the one I had been obviously itching to ask. What advice does he have for writers? The answer I got was one I should have expected. ‘Budding writers should write. Then they should show their work to established practitioners in the field. The first attempts are always awkward. As time goes by, one learns to be less explicit and more controlled, to use images to express one’s thoughts where poetry is concerned, to develop an ear for dialogue if one is writing a play, to produce well-rounded characters in a novel, construct interesting plots, and so on. All this takes time, but it will be worth the effort in the end.’ And with that, we had the perfect closing.

Author: Cassi Camilleri