The world’s oceans support the lives, economies, and health of societies. When the ocean is in decline, a society will also be in decline. Take the Aral Sea Crisis—destroyed by Soviet-era irrigation projects—where a prosperous society used the sea in an unsustainable manner, degrading this resource and their livelihoods. This cycle of decline needs to be turned into a cycle of recovery.Continue reading

What exactly is it that you do?

Research — that would be the simplest way to answer the question above. Really and truly this answer would only apply to a small niche of individuals throughout the world.

Research — that would be the simplest way to answer the question above. Really and truly this answer would only apply to a small niche of individuals throughout the world.

It is a big challenge to explain to people what you do with a science university degree. The questions “Int għal tabib?” (Are you aiming to become a doctor?) or “Issa x’issir, spiżjar?” (Will you become a pharmacist?) are usually the responses. The thing is, people have trouble understanding non-vocational careers — if you are not becoming a lawyer, an accountant, a doctor or a priest, the concept of your job prospects is quite difficult to grasp for the average Joe.

In truth, it is not really 100% Joe Public’s fault — research is a tough concept to come to terms with, ask a good portion of Ph.D. students about that. There seems to be a lack of clarity in people’s minds about what goes on behind the scenes. If you boil it down, everything we use in our daily lives from mobile phones to hand warmers are the spoils of research — a laborious process with the ultimate goal of increasing our knowledge and, consequently, the utility of our surroundings.

“People need to stop feeling threatened by big words and abstract concepts they cannot grasp”

So, then, why exactly is it such an alien concept? I think the reason is that research is very slow and sometimes very abstract. Gone are the days when a simple experiment meant a novel, ground-breaking discovery — research nowadays delves into highly advanced topics, building on past knowledge to add a little bit more. I have complained about this to many of my colleagues on several occasions — and it is more complicated when you are studying something like Chemistry and Physics, or worse, Maths and Statistics — people just do not get it!

Research is exciting. The challenge is how to infect others with this enthusiasm without coming off as someone without a hint of a social life (just ask my girlfriend). It is nice to see initiatives like the RIDT and Think magazine trying hard to get the message out there that research is a continuous process with often few short-term gains. It can be surprising when you realise how much is really going on at our University, despite its size and budget.

To befriend the general public researchers still need to do more. The first step is relaying the message in the simplest terms possible — people need to stop feeling threatened by big words and abstract concepts they cannot grasp. There also needs to be increased opportunities for interaction with research — Science in the City is the perfect example. Finally, I think MCST needs to start playing a larger role — it must work closer to University and take a more coordinated role at a national level. Only then can we begin to explain what us researchers do.

Shattering women’s glass ceiling

The role of women in academia has always greatly interested me. Several years ago, when I was asked to become Gender Issues Committee chairperson at the University of Malta, I readily accepted. Apart from other tasks, the committee has just compiled a booklet about the profiles of senior female academics. Our objectives are twofold: one is to incentivise junior staff to aim higher and move forward in their career; the other, to help sensitise male colleagues to better appreciate the hurdles women face when pursuing an academic career together with raising a family.Continue reading

It’s all in the family

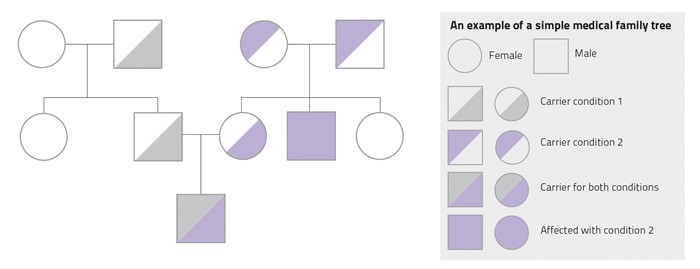

Whatever you inherit comes from your biological family. Unfortunately, this includes disease. Talking about inherited conditions can make people anxious, making them unwilling to discuss the issue with their relatives. After speaking to a number of people my impression is that it seems taboo to discuss these things. People seem to feel that they will be stigmatised or treated differently because of a genetic condition.

A fear of social stigma hinders beneficial research. Research needs the collaboration of patients, since by investigating their condition researchers can in the long run develop a treatment or therapy. Not only that, but avoiding certain discussions means that relatives who might be at risk of developing the same problem would not be aware of it. If a condition is detected too late there might be very little that can be done.

It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together. By building a medical family tree you can easily see who might inherit what. This way, your relatives will learn more about their health and then seek treatment. For example, a cousin might learn that she has an increased risk of breast cancer and would therefore attend screening sessions to catch the cancer before it spreads. Not knowing that something is there does not make it go away but discussing medical matters with your family could save a relative’s life.

“It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together”

Scientific studies need family medical information. Scientific studies using family trees have already shown how useful this information is in identifying families with a high risk for inheritable cancers, like colon and breast cancer. Other research showed that families can benefit from preventative treatments against cardiovascular diseases like diabetes.

Local research has recently used this technique to find new genes, knowledge that can be developed for new treatments. The researchers were studying the genetic background of the protein which carries oxygen in our blood, haemoglobin. This protein switches from foetal haemoglobin to adult haemoglobin 3–6 months after birth. People with thalassemia have a problem with the adult version. Therefore, by studying local families that naturally cope well with the disease, they discovered the KLF1 gene that compensates for the malfunctioning adult protein by raising foetal haemoglobin levels. This was only possible with the help of family trees.

Speaking to a doctor to prepare a medical family tree (pictured) is done in the strictest confidentiality. You may also create your family medical history on https://familyhistory.hhs.gov/fhh-web/home.action to discuss with your family and doctor. I believe that it is in our best interest, apart from being potentially beneficial to the rest of humankind, to help in the creation of our own family medical trees.

If you have any queries when your physician or consultant asks you to prepare a family tree feel free to discuss them rather than avoiding family trees.

Through the Looking Glass

What’s your favourite game? Pacman? Doom? World of Warcraft? Most of us have spent hours immersed in video games, many still do. Prof. Gordon Calleja studies why and how we get so involved in games. Science writer Dr Sedeer El-Showk found out about Calleja’s latest book and game that are gaining worldwide fame.

Assisted Conception — IVF and other procedures

Assisted conception procedures arose as a type of treatment for infertility. They opened a whole new range of possibilities for couples that were unable to have children due to a variety of problems. Initially, the difficulty addressed was of blocked or absent fallopian tubes in women. This prevented the oocyte from making contact with sperm, hence preventing the formation of an embryo. Naturally, this also prevented an embryo from moving into the uterus, implanting itself, and developing into a foetus.

In vitro fertilisation bypasses tubes by obtaining oocytes from the ovaries and fertilising these oocytes outside the body (in vitro — in glass). The procedure became a reality in humans with the pioneering work of Steptoe and Edwards and the delivery of Louise Brown in 1974. She gave birth naturally in 1999.

“In our society, infertility is becoming more common and 8 out of 10 couples can experience problems”

With the further development of ICSI (Intra cytoplasmic Sperm Injection) it was possible to fertilise an oocyte (egg) with an individual sperm. This was a breakthrough therapy for men with low or absent sperm counts.  When sperm are lacking in the ejaculate, a doctor can retrieve them directly from the testicles, or the epididymis (a tightly coiled tube from the testes to the rest of the body). The procedure is known as TESA or PESA. In combination with ICSI, these techniques made it possible for these men to father children.

When sperm are lacking in the ejaculate, a doctor can retrieve them directly from the testicles, or the epididymis (a tightly coiled tube from the testes to the rest of the body). The procedure is known as TESA or PESA. In combination with ICSI, these techniques made it possible for these men to father children.

In our society, infertility is becoming more common and 8 out of 10 couples can experience problems. This simple statistic makes these procedures increasingly important. Nowadays, even couples with the most severe problems can become parents.

These procedures have been mixed in controversy from the beginning, with most countries allowing science to proceed within certain safeguards. This restrained approach allows for progress.

Regrettably, infertility still carries a large stigma. The thousands who have benefited from these and other simpler infertility procedures (they precede attempts for assisted conception) do not speak out. Normally they don’t because of how society would perceive them or their children.

IVF is a physically, psychologically, and financially demanding procedure. Couples normally only proceed after having spent a considerable time beforehand seeking help, investigating, and trying alternative simpler treatments. It is usually the final recommended solution to the problem.

IVF essentially means that fertilisation of the oocytes occurs out of the body. The oocytes are then fertilised with sperm and in a percentage of cases this is successful and an embryo starts to develop.

This article continues the focus on IVF from last year’s opinion piece by Prof. Pierre Mallia. Other local experts have been contacted and we are open for further opinions and comments from our readers.

Attention, Research ahead!

B yDr Ernest CachiaContinue reading